Sacred Stories as Windows and Mirrors: A Pre-Kindergarten Class Reflection

By Jennifer Hook and Abbey Unes

Creation School is nestled in the hills of the Sonoran Desert in the Rincon Mountains of southern Arizona, just east of Tucson. We believe that children gain much from connecting with the natural world around them. Our guiding philosophy states that children learn through exploration and make sense of the world through intellectual discovery; the physicality of their bodies; an emotional connection to adults and peers; their understanding of themselves and their place in the community; and the wonder and appreciation for the miracle of creation and its Creator. "Creation teachers strive to create environments that are full of wonder, curiosity, magic, beauty, and natural accents" (Hook, 2020). Our children's senses play a large role in their development and we are careful to design an environment to encourage exploration that supports the best learning environment for the child.

Together we taught one of the prekindergarten classes. Jennifer has been a teacher for 35 years (preschool through college) and is also Creation's school administrator. Abbey is a registered nurse and has worked in Pediatric Intensive Care and as a nursing clinical instructor. After raising her four children, this year she became a first-year prekindergarten teacher.

Our pre-kindergarten classroom included 10 children from nine different families, six boys and four girls, ranging in age from 3 to 5 years old. We met twice a week for approximately three hours a day. The children were predominantly from White middle-class families. One child spoke English as a primary language and Arabic as a second language within his home. All other children spoke English as their primary language. Two-thirds of the families claimed Christianity as their religious affiliation, and one-third did not adhere to any religious beliefs.

In this vignette we share how we used Bible stories from our curriculum along with global literature to introduce our children to the concept of windows and mirrors (Bishop,1990). Our goal was to give both teachers and children a tool for seeking identity through children's literature.

Forming Identity through Global Literacy

The foundation for our Global Literacy project follows the sacred stories of the Bible. Stories based on oral traditions or religious writings that are considered spiritual for a culture are called sacred stories and, in our case, our school is based around Christianity and the Bible. The Bible can be viewed as a credible book in the global literature canon. It was written by approximately 40 different authors, some of whom are named while others are anonymous, and the complete Bible has been translated into 704 languages (Wycliffe Global Alliance, 2020). It speaks to the universal human condition and provides an array of characters across ancient history.

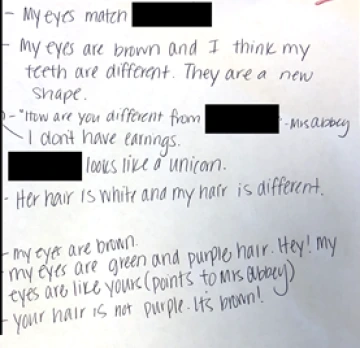

Figure 1. Chart of students’ suggestions of their similarities/differences from each other.

We centered our lesson plans around Bible stories for the year and built our curriculum and learning around the stories to include outside play, blocks, dramatic play, art, science/math, music, circle time, and book center. Creation School belongs to Quality First, which is a taxpayer funded program to ensure high-quality environments for young children. We follow their guidance of book selection to include multiple perspectives, a representation of diversity, and authors from different cultures and countries, similar to our focus with global literature. Through our sacred stories from the Bible, we see each child as a child of God who is made in God's image and likeness and so we treat others as we would want to be treated, we accept similarities and differences between us, and we recognize each of us as special. During one lesson, we made a list of our similarities and differences. Figure 1 lists, for example, similarities and differences of eye color, hair, and teeth.

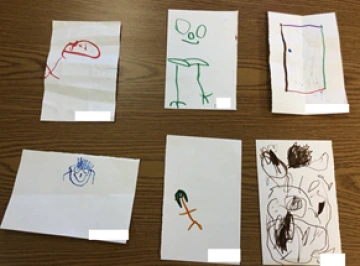

In another lesson, children drew self-portraits of themselves (see Figure 2). We were curious about the drawing of a door as a self-portrait, but Shovana (age 4) explained that it was a picture of her hiding behind the door. We wondered if Shovana was making the early representations of her understanding that pictures can mean many things.

Figure 2. Students’ self-portraits, including Shovana’s (age 4) of her hiding behind the door.

In our classroom, we focused on a particular Bible story each week and created our lesson plans around that core story. We then chose books for our literacy component that supported the Bible story. For example, during our theme "Jesus Teaches Us to Pray", we read "How to Pray" from the Jesus Storybook Bible (Lloyd-Jones, 2007, p. 222) and discussed how and where we can pray. Short (2009) wrote that, "children bring their personal experiences of living in the world and being part of specific cultural groups and social contexts to school... When students recognize the cultures that influence their thinking, they become more aware of how and why culture is important to others" (p. 4). Some children reported they prayed at meal or before bed, while others thought that was strange. During snack times, we asked if children wanted to have a turn leading our prayer. Occasionally, a child felt comfortable leading the prayer, but often they referred to our classroom prayer instead of a prayer they said at home, feeling more comfortable in our classroom culture. Additionally, we placed multiple different prayer books in our book center to encourage discussion about the different types of prayers.

Figure 3. Mrs. Abbey making hummus with help from a student.

As another example, when we read the Bible story about Moses and the Exodus, we considered the kind of food Moses and his family may have eaten, such as unleavened bread and manna, which would have taken the place of the bread we eat today. Moses may have eaten hummus with his bread and as a class, we made hummus using a recipe from Mrs. Abbey's grandmother-in-law, a recipe that had been passed down from multiple generations (see Figure 3). Some children were familiar with what hummus was, while others had never tried it before. A child who hears Arabic as a second language was familiar with hummus but did not give insight beyond "I eat that at home sometimes," to show he was making connections between reading the Bible story, making hummus, and something he experienced at home. Short's (2009) definition of intercultural understanding includes that learners "develop an awareness and respect for different cultural perspectives as well as the commonality of human experience" and "value the diversity of cultures and perspectives within the world" (p. 3). Allowing children to have a similar experience as a character within a story, in our case a Bible story, helps to broaden their horizons and discover their own identities (Laminack & Kelly, 2019).

Windows and Mirrors

In our classroom, books served a major role to create introspective and extrospective thinking, otherwise termed as mirrors and windows (Bishop, 1990). Laminack and Kelly (2019) state "the right book, at the right time, can span the divide between where the reader stands in this moment and alternate views, new ideas, and options not yet considered" (pg. xiii). Using a book as a mirror helps readers understand their identities and reflect on the world in which they live, such as defining themselves through language, values, and specific cultural norms or foods, feelings and emotions. The window concept helps readers go beyond their immediate worlds to learn about other places, people, emotions, and experiences that are new to them.

Figure 4. Chloe, age 4, looking at herself in a mirror.

Early in the school year, we began to introduce the terms "windows" and "mirrors" to frame our experiences with books and writing. Developmentally, preschool children can "think about objects, people and events without seeing them; however, although less than before, still think they are the center of the world and have trouble seeing things from someone else's perspective" (American Psychological Association, 2017). Young children also tend to be concrete thinkers, working in the here and now. Abstract thought using metaphors can be a difficult concept that needs to be scaffolded for the children by thinking aloud with them, using why and how questions (Ylvisaker 2006).

Introducing the concept of windows and mirrors as a path to understanding identity started as a concrete exercise. We added mirrors to our writing area, invited the children to look at themselves in them, and asked, "What do you see?" (see Figure 4). The children's responses included:

- "I see Liam and James playing together behind me." Julio, age 4.

- "I see myself playing with blocks." Grace, age 4.

- Chloe, age 4, stated, "Makes me beautiful!" (see Figure 4)

We then encouraged the children to think about what they see when they look through a window. We provided picture frames as a way to visualize the window space. When given this task, some children ran to the classroom windows and described our outdoor area. Some, such as Thomas, age 5, described the view from the windows of their homes (see Figure 5). He commented, "I see flowers, rocks, and grasshoppers through my window at my house."

Figure 5. Thomas, age 5, imagining the view from a window at his home.

Stories as Mirrors and Windows

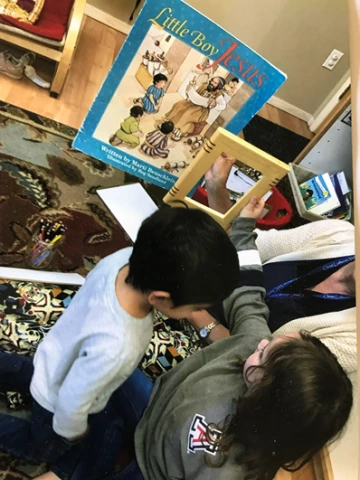

It was clear that the children had previous knowledge about the functionality of mirrors and windows. Now our work was to scaffold their understanding of how stories can function as tools to help us see ourselves and understand beyond ourselves. We kept the mirrors and picture frames in the book area to use as a tool when reading stories. We simplified the concepts to be that mirror books are about things that you know, like yourself and your environment. Window books are about people or things you do not know but you can learn. As we read books to children, children discussed whether a book would be like a mirror or a window. Chloe, age 4, guessed that the story about Jesus as a little boy would be a window book because the picture of his school looked different than her school (see Figure 6).

Another activity was to sort book titles as mirrors and windows. We asked, "Which books are about things you know? Which books are about things you don't know?" Taking a random selection from our book basket, the children organized the books by category. The window books included A House for Hermit Crab (Carle, 2013), a story about marine life (which is not a common experience for desert-dwelling children) and Dragon Dancing (Schaefer & Morgan, 2006), a book about a tradition not often celebrated by the families in our school.

Figure 6. Chloe, age 4, giving her opinion that the story of Jesus’ school was a window

book.

As mirror books, children chose Germs Are Not for Sharing (Verdick & Heinlen, 2006), Froggy Goes to the Doctor (London & Remkiewicz, 2004), Bear Feels Sick (Wilson & Chapman, 2006), and There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Shell (Colanda & Lee, 2006). It was interesting to see that the books about being sick were in the mirror group. We hypothesized that it was indicative of children living in the middle of a pandemic. When asked why they placed There was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Shell (Colanda & Lee, 2006) in the mirror group, the children remarked that the old lady was their teacher, Mrs. Hook!

Figure 7. A drawing from Hannah’s, age 5, book about herself.

Writing Mirror Books

We believe writing supports reading, so the children created several mirror books. "A Book about Me!" chronicled what each student knew about themselves and gave teachers a window into students' understanding. Hannah, age 5 stated in her book, "I love flamingos! I love Alicia! I love God! I go at Baby School when I was a baby. I am good! I love my family! Chickens make me feel happy!" (see Figure 7).

We noted that Hannah drew from her different life experiences as she dictated her book, including a recent trip to the zoo and the hatching of baby chicks at the school.

Learning From Different Perspectives

As we came to the end of the school year, we wanted to explore the concept of recognizing and learning from different perspectives. Laminack and Kelly (2019) stated in their introduction: "We want readers to explore both the connections between their own worlds and those they read about and how they see themselves and others in new ways as a result" (p. xviii).

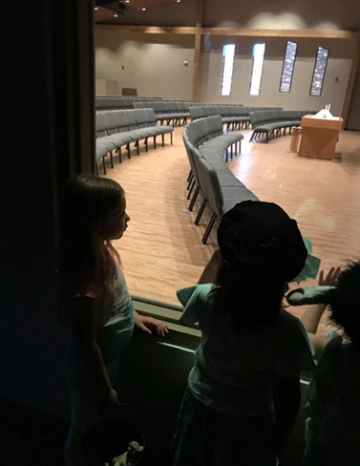

Figure 8. Children standing in the nursery, looking through the one-way glass window into the church.

To physically manifest this idea, we brought the children to the recently completed church on campus. The children were able to view the church sanctuary for the first time. Because of the pandemic, none of the children had attended services there. We started in the nursery and looked through the one-way glass window into the church (see Figure 8). The children talked about what they saw, and asked questions about the furniture, different areas, and their purposes.

Then we walked through the door around to the other side to stand at the mirrored side of the glass (see Figure 9). We talked about how this place was first a window through which we could see things we did not know about, but we could learn. Then this place became a mirror in which we could see ourselves in this space. We are part of something bigger than ourselves, a part of a larger community of faith. The children were intrigued by the experience and could readily understand the unique feature of the mirror. However, they struggled to make any deeper connection to either themselves or books.

Closing Thoughts

Figure 9. Children in the church, looking at the mirrored side of the glass.

Our goal with this project was to give both teachers and children the tool of windows and mirrors for seeking identity through children’s/global literature. The concept of windows and mirrors was new for us and we were excited to use the tools as a fresh way to explore identity through our sacred stories. The children enjoyed using the small mirrors and picture frames as prompts in their writing and drawing and took pride in their mirror books. We soon realized, however, that the developmental level of the children, and the brevity of time that we had with them, produced challenges in working through the ideas to a deeper level of understanding about identity. In our effort to teach windows and mirrors, we missed opportunities to follow the children’s lead in their own search for identity.

Looking ahead, we understand that reading to children and using stories as windows and mirrors can help children grow in their understanding of identity. As teachers of young children, we want to use the windows and mirrors tool when choosing stories for the classroom and to engage children in deeper conversations about themselves, their personal experiences, and who they are in relation to others. In the future, though, instead of teaching the windows and mirrors tool, we hope to focus more on the children and engage them in discussions around global literature that invite them to use the mirrors and windows tool to reflect on themselves and others, thereby deepening their understandings. We can then encourage children to reflect on their identities through ownership of their learning in a developmentally appropriate way.

References

American Psychological Association. (2017). Cognitive and social skills to expect from 3 - 5 years. https://www.apa.org/act/resources/fact-sheets/development-5-years.

Bishop, R.S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives, 6(3), ix-xi.

Hook, J. (2020, July). What is a Creation teacher? Presentation at a Teacher Inservice at Creation School, Vail, AZ.

Laminack, L., & Kelly, K. (2019). Reading to make a difference: Using literature to help students speak freely, think deeply, and take action. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Short, K. (2009). Critically reading the word and the world: Building intercultural understanding through literature. Bookbird: A Journal of International Children's Literature, 47(2), 1-10.

Wycliffe Global Alliance. (2020). 2020 scripture access statistics. https://www.wycliffe.net/resources/statistics/.

Ylvisaker, Mark, PhD. (2006). What are concrete and abstract thinking. http://www.projectlearnet.org/tutorials/concrete_vs_abstract_thinking.html.

Literature Cited

Carle, Eric. (2013). A house for hermit crab. New York: Little Simon

Colanda, L., & Lee, J. (2006). There was an old lady who swallowed a shell. New York: Scholastic.

Lloyd-Jones, S. (2007). Jesus storybook bible. Nashville, TN: ZonderKids.

London, J., & Remkiewicz, F. (2004). Froggy goes to the doctor. London, UK: Puffin Books.

Schaefer, C.L., & Morgan, P. (2006). Dragon dancing. London, UK: Penguin.

Verdick, E., & Heinlen, M. (2006). Germs are not for sharing. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit.

Wilson, K., & Chapman, J. (2006). Bear feels sick. New York: Little Simon.

Jennifer Hook has been in the education field for 35 years, working with students from preschool through college. She currently serves as a PreK teacher and school administrator.

Abbey Unes has been a registered nurse for many years. This was her first year as a pre-kindergarten teacher at Creation School.

© 2021 by Jennifer Hook and Abbey Unes

WOW Stories, Volume IX, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work by Jennifer Hook and Abbey Unes at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/volume-ix-issue-2/6.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551