Chinese Lunar New Year: A Celebration of Culture

Vanessa Hoang

Vail, Arizona, is a suburb of Tucson, with a population of less than 11,000 persons, only 3% of whom are Asian (U.S. Census Bureau Quickfacts, 2010-2019). I am part of that 3%. I was born in Seoul, South Korea. My parents adopted me when I was six months old and I grew up with American and Latinx traditions. To be honest, I know very little about my Asian heritage, until I married my Vietnamese husband and had children. The year 2020 was my first year attending a Lunar New Year celebration. The sights, the sounds and even the smells of Vietnamese cuisine were a new experience. As a second-year preschool teacher (my degrees are in business areas), I was excited to share these experiences with my students.

Creation School is an early learning school with classes for students from two-years-old to first grade. Our school celebrated National Lutheran Schools Week and Lunar Year simultaneously. We introduced, shared, and inspired our young students to learn about a new year’s tradition from across the globe – Chinese Lunar New Year – through hands-on experiences, storytelling, and personal experiences. Our hope was that through reading and discussing global literature on Chinese New Year along with these experiences students would appreciate and begin to understand the connections, differences, and complexities in our world (Acevedo, Pangle, Kleker, and Short, 2017; Corapi and Short, 2015). In this vignette, I share our school’s experiences with this cultural celebration which is not widely observed in our area.

What is Lunar New Year?

Lunar New Year is a festival that celebrates the beginning of a new year, based on the traditional Chinese calendar or lunar calendar, when there is a new moon. This festival is typically celebrated over fifteen days and is also known as Chinese New Year, Spring Festival, and Lunar New Year. Each year in the Chinese lunar calendar is named for one of 12 animals: rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, goat, monkey, rooster, dog, rat, and pig (Otto, 2015). After 12 years the cycle begins again. This year, 2020, is the year of the rat.

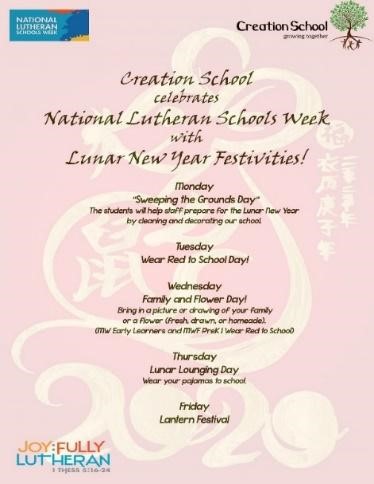

Figure 1 details our school plans for our weeklong celebration. To help students understand Chinese beliefs, ways of life, and the “whys” of traditions and celebrations, we started the week with cleaning and sweeping the grounds. Similar to our own traditions of spring cleaning, Chinese cultures clean their homes prior to each new year, symbolizing washing and cleaning away the bad from previous year, and starting the new year fresh. We discussed this tradition with students and they helped us clean our classrooms by sweeping the floors or wiping down tables and chairs. Participating in these practices built on “universal aspects of [the] children’s lived experiences while also looking at unique aspects” of our own and Chinese communities (Acevedo et al., 2017, p. 24). Cleaning for the new year also helped students gain a sense of community and responsibility. Students and staff were encouraged to wear red, symbolizing good luck and fortune. The week concluded with a lantern festival and dragon dance with students who were on campus on Friday. Throughout the remainder of the vignette, I share snippets of how my class of early learners and the pre-kindergarten and kindergarten/first grade classes introduced aspects of Chinese culture and explored Chinese New Year.

Celebrating Chinese New Year in Our Classrooms

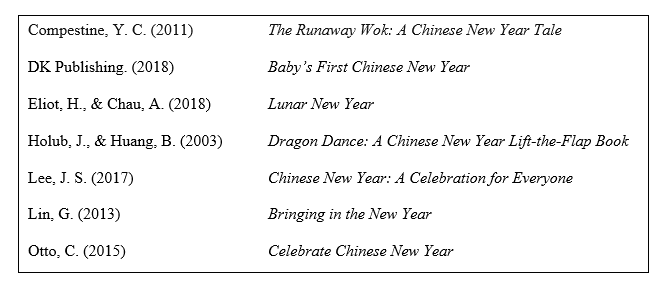

Since we knew students living in the Arizona desert had limited experiences with Chinese New Year celebrations, we relied heavily on children’s literature to introduce it to them and provide information. While the information was new, themes in the books, such as families, friends, and celebrations, helped students connect their lives and experiences to it (Acevedo et al., 2017). The stories (both fiction and nonfiction) engaged students and helped them make sense of their new learning (Corapi & Short, 2015). A sampling of the books we used in our classrooms is found in Figure 2.

Early Learners

As the Early Learners preschool teacher, my class had five students, ages two to three years at the time of our celebration. Of the two girls and three boys, three were European-American and one each were African American and Latinx. My hope when teaching is to always include the five senses in any topic/theme experiences which is a challenge when we only meet two times a week.

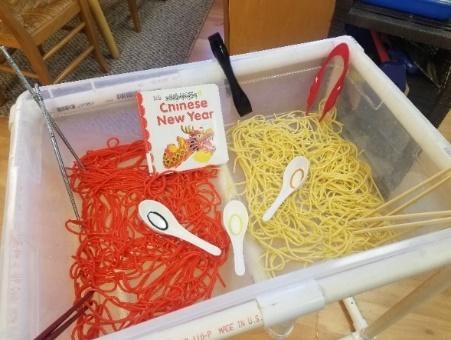

On the first of our two days, I introduced Chinese New Year, explained the basics of the celebration, and read Baby’s First Chinese New Year (DK Publishing, 2018). This book shows bright colors, basic elements of the holiday, and the various yearly animals. To encourage students to use their fine motor skills, I set up a sensory bin with red and “golden” (plain) cooked spaghetti noodles. Students used different utensils, tools, and their hands to pick up the noodles (see Figure 3).

We explored art by creating our own egg carton dragons with red and gold paint (see Figure 4). I used the book Celebrate Chinese New Year (Otto, 2015), mostly for the photographs, so students could visualize aspects of Chinese culture. Students were mesmerized by the colors and various dragon costumes throughout the book. Towards the end of this book was a map which showed where the Chinese New Year originated.

I also showed a video I had taken of a dragon dance from the Vietnamese New Year celebration I had attended the previous weekend with my family. Students enjoyed the sights and sounds of the dragon costume. Our oldest student suggested we make a “plane” with our chairs and travel to see the dragon dance. She even remembered seeing the map and told me, “Let’s go to the place on the map, like in the book” (see Figure 5). I grabbed the book and went to the map and we flew across the world (with our stuffed animal friends) for our dragon dance.

On our second day that week, we listened to the beat of the drums from a YouTube video. We danced with our dragon creations and attempted to follow the drumbeats, slow versus fast movements. We also did a food tasting of white steamed rice and oranges, two popular foods found in lunar celebrations. I shared that rice is a staple food at every meal and oranges symbolize the full moon.

Over the course of our two days that week, I explored many facets of the Chinese New Year with these two and three-year olds. I wanted to help them begin to realize that while we all share some things, like families and traditions, not everyone in the world lives, acts, and celebrates like we do in Vail, to encourage the development of their intercultural understandings (Acevedo et al., 2017). While our days were filled, I was captivated by how engrossed students were in this new celebration. A few weeks after our celebration students continued to incorporate “flying” in their daily dramatic play, often referring to our trip across the world.

Pre-Kindergarten Classes

The two pre-kindergarten classes (four and five year olds) explored and read a variety of books about Chinese New Year, including Dragon Dance: A Chinese New Year Lift-the-Flap Book (Holub & Huang, 2003), Bringing in the New Year (Lin, 2013), Lunar New Year (Eliot & Chau, 2018), Celebrate Chinese New Year (Otto, 2015), and Chinese New Year: A Celebration for Everyone (Lee, 2017). Many students commented on the bright colors in the costumes. Students also discussed ways their lives were like and different from those portrayed in the books. The photographs in some of the books provided them with a realistic sense of the Chinese New Year. With the Chinese New Year’s books as their guide, students also created egg-carton dragons. When Ricky commented, “I don’t know how to do this,” my son Noel (who had attended the Vietnamese celebration with me and seen a dragon), replied, “just follow mine, I know what they [dragons] looks like.”

Kindergarten/First Grade Class

The kindergarten/first grade class explored the book, The Runaway Wok: A Chinese New Year Tale (Compestine & Serra, 2011), which tells the story of a poor family and their adventure with a runaway wok during Chinese New Year. Through the use of colorful and vivid illustrations, students learned the importance of Chinese New Year and generosity. The reading of The Runaway Wok also brought a discussion of character traits and behaviors that may be different in other cultures.

The class had a visit from a local Korean exchange student, who taught students how to write their names in Korean. Students discussed how difficult the characters were compared to writing their names in the English alphabet. Students mentioned how they felt like they were drawing their names rather than writing them.

Final Reflections

Our school’s week-long celebration of the Chinese Lunar New Year provided different cultural experiences for young students. Through our explorations of the similarities and differences in culture, traditional practices, celebrations, foods, symbolic color meanings, and alphabet writing, students learned about other ways of living and being across the globe which strengthened their intercultural understandings. Sharing Chinese New Year with students in the Sonoran Desert will have a lasting impression on both them and us.

References

Acevedo, M., Pangle, L., Kleker, D., & Short, K. (2017). Engaging young children with global literature. The Dragon Lode, 35(2), 17-26.

Corapi, S., & Short, K. G. (2015). Exploring international and intercultural understanding through global literature. Research Report, Web publication, Longview Foundation. http://wowlit.org/Documents/InterculturalUnderstanding.pdf

U.S. Census Bureau Quickfacts: Vail, Arizona. (2010-2019).

https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/vailcdparizona/PST120219#qf-headnote-a

Children’s Literature References

Compestine, Y. C., & Serra, S. (2011). The Runaway Wok: A Chinese New Year Tale. New York: Dutton.

DK Publishing. (2018). Baby’s First Chinese New Year. New York: DK Publishing.

Eliot, H., & Chau, A. (2018). Lunar New Year. New York: Little Simon.

Holub, J., & Huang, B. (2003). Dragon Dance: A Chinese New Year Lift-the-Flap Book. New York: Puffin.

Lee, J. S. (2017). Chinese New Year: A Celebration for Everyone. Custer, WA: Orca

Lin, G. (2013). Bringing in the New Year. New York: Knopf.

Otto, C. (2015). Celebrate Chinese New Year. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic.

Vanessa Hoang teaches the Early Learners class at Creation School, Vail, Arizona.

© 2020 by Vanessa Hoang

WOW Stories, Volume VIII, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work by Vanessa Hoang at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/volume-viii-issue-1/7/.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551