Inquiry into Cultural Authenticity in Traditional Literature: Sita’s Ramayana

“...Myth might be defined simply as 'other people’s religion,'..." Joseph Campbell

While folktales and fables are traditional literature of a secular nature, myths are sacred narratives. To people within a particular religious group, myths are true accounts of past events. Myths explain how the world came to be and how people’s behavior, societal customs, and institutional norms were formed. The main characters in myths are usually gods or heroes with supernatural powers and the humans with whom they interact. “…Myth might be defined simply as ‘other people’s religion,’ to which an equivalent definition of religion would be ‘misunderstood mythology,’ the misunderstanding consisting in the interpretation of mythic metaphors as references to hard fact” (Campbell 27).

The Ramayana, an essential part of the Hindu religious canon, was most likely written in the 4th century BCE. Ascribed to Hindu sage Valmiki, this epic poem tells the story of Rama, the incarnation of the God Vishnu, and his journey to become an exemplary king. The most oft-told sections of the Ramayana are the abduction of Rama’s wife Sita by his adversary evil king Ravana, Rama’s rescue of Sita with the help of the monkey Hanuman, and Sita’s ultimate banishment to the forest. The Ramayana is not just a story; it is an allegory. It represents the teaching of ancient Hindu sages and is intended to show readers and listeners the path of dharma or path of “righteousness,” which shows the way to living in harmony with the universe.

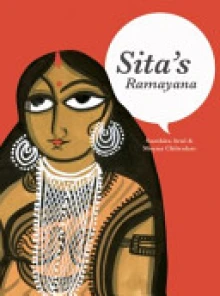

According to a note at the end of Sita’s Ramayana by Samhita Arni, illustrated by Moyna Chitrakar, this graphic novel version is closely related to the Patua folk-art form. In this tradition, Patua artists paint a series of images on a scroll, which is unrolled and referred to as the story is told or sung or danced. Patua, a caste of people living in the West Bengal region of India, have been painters by trade for many generations. Hindu deities are the main topic of their work. Patua artist Moyna Chitraka, whose last name literally means “scroll painter,” painted the illustrations for this book before the author wrote the print. The graphic novel format of presenting visual information in panels parallels the Patua tradition of visually recounting texts as a series of scenes.

In this book, Chitraka paints Sita with wide eyes that hold the reader’s attention in their gaze and reinforce the centrality of Sita’s voice in this retelling. According to the note by V. Geetha of Tara Books, Sita’s Ramayana is not the only version of this myth told from the female point of view. One such was told by Bengali female reteller Chandrabati who lived in the 16th century. “These songs and ballads were perhaps the creations of women, who sang as they worked at home and outside, and who identified no doubt with this tale of womanly suffering and fortitude” (150). Chitraka’s illustrations encourage readers to empathize with this woman who thwarts the advances of her husband’s adversary only to be banished to the forest because Rama cannot shake off his unfounded suspicions and cannot deal with the rumors spread among his people.

Author Samhita Arni’s print includes passages that reflect the values that are central to Valmiki’s poem: trust, honor, loyalty, and the terrible consequences of war. “Violence breeds violence, and an unjust act begets greater injustice” (16). “War, in some ways, is merciful to men. It makes them heroes if they are the victors. If they are the vanquished—they do not live to see their homes taken, their wives widowed. But if you are a woman—you must live through defeat… you become the mother of dead sons, a widow, or an orphan; or worse, a prisoner” (120). With its decidedly feminist perspective, Sita’s Ramayana highlights the tragedy that can result from disharmony between husband and wife and the painful consequences to women, children, and ordinary people when their lives are determined by competition between powerful men.

In this graphic novel, young adults have a visually-appealing, fast-paced, action-packed story that makes this ancient Hindu text accessible to 21st-century readers. Readers who are unfamiliar with this religion will learn about key figures, including gods, kings and queens and their relatives, and animal helpers. (Arni and Chitraka provide a helpful genealogy chart at the front of the book.) Readers will also gain insight into foundational Hindu values. The characters in this allegory are fraught with moral dilemmas; there are significant themes for readers to consider.

For me, Sita’s Ramayana has many parallels with Tiger Moon (Michaelis), which LS5633: The Art of Storytelling students discussed on the WOW Currents in March 2012. Sita like Safia in Tiger Moon struggles to maintain her virtue while imprisoned and must be rescued. Sita is rescued by her husband Rama, the incarnation of the God Vishnu, and Safia by Farhad, who is chosen to do so by Lord Krishna. Both Rama and Farhad are aided in the rescue by animal helpers. Hanuman, a brave and wise monkey, helps Rama rescue Sita. A white tiger named Nitish, which means “Lord of the Right Way” in Hindi, aides Farhad in freeing Safia. I believe some readers may better comprehend the Hindu religious and cultural aspects of Tiger Moon if they read a myth like Sita’s Ramayana first.

How did you respond to this myth? What do you think about the feminist perspective of this particular version and how might it be different from Valmiki’s poem? Does sufficient background knowledge about a culture help the reader or storyteller access the deeper meanings in myths? Is this more important in understanding and communicating myths than it is in folktales and fables? What are some of the challenges you see for storytellers in retelling myths from the perspective of cultural outsiders?

Postscript: This month in our inquiry into cultural authenticity and accuracy in literature and storytelling, we have discussed five traditional literature books written and illustrated for children and young adults. We started with our responses to the literature and then looked more closely to explore the cultural aspects of each story with a focus on authenticity. As in all inquiry learning, we have raised as many questions as we have answered. We may not have achieved consensus regarding these challenges for storytellers, teachers, and librarians, but we have demonstrated a willingness and openness to explore how we can accurately and more authentically share these folktales, fables, and a myth with young people. Thank you all for sharing your journey on the WOW Currents where we can revisit and continue to reflect on our conversation.

Works Cited

Arni, Samhita. Sita’s Ramayana. Berkeley, CA: Groundwood, 2011. Print.

Campbell, Joseph. The Inner Reaches of Outer Space: Metaphor as Myth and as Religion. Novato, CA: New World Library, 2002. Print.

Michaelis, Antonia. Tiger Moon. Trans. Anthea Bell. New York: Amulet Books, 2006/2008. Print.

Please visit wowlit.org to browse or search our growing database of books, to read one of our two on-line journals, or to learn more about our mission.

During our group’s original discussion concerning Sita’s Ramayana, we talked a lot about feminism and Sita’s role in this version. We saw Sita as a very sympathetic character, and enjoyed exploring her growth as a character. Her steadfastness towards Rama, even when he betrayed her at the end, was beautiful to witness, as well as heartbreaking. In Zakeer’s interview with author Samhita Arni, they discussed the feminism of this graphic novel version versus the original, older version. When questioned why she chose this version of Sita to portray, Arni said, “The Sita that we are most familiar with today, the demure and chaste one, is not the kind of ideal that girls like me, growing up with feminist mothers and encouraged to pursue what we want, can identify with” (2012). For Arni, then, the original version of Sita was not easy to identify with in today’s world. I agree that changing Sita from completely demure and silent to a strong character in her own right makes her journey connect more with today’s readers.

I definitely think background knowledge concerning a culture deepens and expands the meanings of a myth. By knowing the background, the reader and storyteller can understand to a further extent where the characters are coming from, the motivation behind their actions, and then pinpoint the differences in the particular version you may be reading or retelling. I would agree that it is more important in myths than in folktales to know cultural authenticity. Arni says in Zakeer’s article (2012) that she struggled not to deviate from the original too much in order not to offend any religious sensibilities. She stated, “I don’t intend, I don’t want in any way to offend religious sensibilities, but I want to engage with the questions and concepts the Ramayana asks and puts out. It’s also a beautiful literary tradition, in all its various forms, and I think to keep the epics and traditions alive one must retell these stories, so that they continue to be relevant to our lives” (Zakeer). I agree that it is incredibly important to maintain cultural authenticity, even in retellings. While the reader/writer/storyteller may change some things, or the views of some characters and situations, knowing the culture and background information is essential to keeping the heart of the story accurate and meaningful. Furthermore, by understanding the groundwork, one can really begin to explore and expand upon the story.

Works Cited

Arni, Samhita. Sita’s Ramayana. Berkeley, CA: Groundwood, 2011. Print.

Zakeer, Fehmida. “A Feminist Ramayana.” India Currents: The Complete Indian American Magazine. 2012. Web. Accessed April 20.

-- Kelsie

As Kelsie mentioned above, our group discussed Sita's character in detail. We were all captivated by her loyalty and undying love and ultimately her ability to forgive. Sita's character was very empathetic towards others even when not deserving. As a mother, I found it especially puzzling when Sita leaves her beloved sons with Rama after he betrayed her. This part of the story left me with many questions and I believe this happened because of the cultural differences and the lapse of time. Women have come a long way since this story originated and perhaps that is why it is difficult for some of us, like myself raised by very self-sufficient parents where both are seen as equals, to fully understand Sita's submission to Rama.

It would have benefited me tremendously to be more familiar with the Hindu culture prior to reading this story. The background knowledge just wasn't there and that affected my understanding of the characters and their actions. Especially, in this story since it is a myth. Folktales tend to be a little more "flexible" in understanding because of the themes that cross cultures and expand time. Nonetheless, curiosity came over me and I quickly grabbed some books from our library to expand my knowledge. So, yes, background knowledge is important to fully understand a myth, however, a lack of knowledge also breeds curiosity and that leads to discovery.

Norma

Arni, Samhita. Sita’s Ramayana. Berkeley, CA: Groundwood, 2011. Print.

Excellent point, Norma! While background knowledge certainly aids a lot in understanding myths, not have prior knowledge certainly does open the door of curiosity! Thank you for bringing that point up. What an interesting project it would be, I think, to start backwards. Start with the body or bodies of work from another culture, read and discuss them, THEN go back and research the culture to connect it to today’s. It could be a very good school project!

Rereading the introduction, I was struck again by one sentence: “With its decidedly feminist perspective, Sita’s Ramayana highlights the tragedy that can result from disharmony between husband and wife and the painful consequences to women, children, and ordinary people when their lives are determined by competition between powerful men.” While this theme – competition between powerful men – stays true throughout all different versions of the Ramayana, I feel Arni’s version provides some reasoning why Sita acts as she does because of this struggle. She puts up with these fights and struggles and is beaten down and disbelieved and not trusted. Maybe, in the end, she leaves her sons because she sees the same thing in them she saw in her husband. I would hate to think so negatively, but perhaps she has simply reached her breaking point at the end of the myth, and has given up faith in all powerful men, even her own sons.

Sita’s Ramayana certainly poses many interesting questions!

Arni, Samhita. Sita’s Ramayana. Berkeley, CA: Groundwood, 2011. Print.

- Kelsie

My original response to this myth was one of intrigue. I appreciated the feminist perspective but wondered about the separation of mother and children at the end as Norma mentioned above. Now that I have read Dr. Moreillon’s post, and some other literature on the web, I understand that the depth of this ancient story is not easily tapped and am even further intrigued by its relation to Sanskrit and meditative practices.

As for a review of this multi-level tale as a modern graphic novel: I mentioned once before that the art captivated me immediately. I researched the artist and came across an interview in which she expressed her intent with the art and aligning herself with the story in general. I found that Moyna Chtirakar has witnessed much suffering in her native village due to oppression of women by their husbands, and men in general. Chitrakar views Sita’s Ramayana as an opportunity to counsel these women and hopefully prevent them from suicide which is an immediate concern in this region. Chitrakar is quoted as saying “If Sita could endure all the disappointments and cruelty that she had to suffer with humanity and compassion, so can the women of the villages in Bengal” (Chitrakar 2012). This look into the artist’s intentions adds tremendously to my admiration for the whole piece.

While, I understand and agree with the above comment which declares lack of background knowledge as a useful tool in motivating curiosity, I must say that knowing as much as one can about the creation of a piece (whether that knowledge comes before or after consumption) is necessary to for sufficient appreciation to be experienced. Additionally, if the knowledge is gained after initial consumption, I would assert that a second encounter should be mandatory as the audience will certainly gain a new understanding of the material once the gaps are filled in with prior knowledge.

I have not had a chance to look over the following web site at length but I found it interesting and relevant for comparing Sita’s Ramayana to others:

Further Reading: http://valmiki.iitk.ac.in/index.php?id=introduction

Works Cited

Arni, Samhita, Moyna Chitrakar, and Vālmīki. Sita's Ramayana. Toronto: Groundwood, 2011. Print.

Basu, Anjana. "Women's Web." Womens Web. Women's Web, 29 Feb. 2012. Web. 03 May 2013.

Geervani, P., and K. V. Ramakrishnamacharyulu. Valmiki Ramyana. Valmiki Ramyana. Rashtriya Sanskrit Vidyapeetha, Aug. 2005. Web. 3 May 2013.

In regards to Rachel's comment: I agree that a second reading or viewing would be beneficial if research into the culture is done after the initial reading of a work. I would think such a process (reading, research, a secondary reading) would really open the eyes of the reader. They would be able to see more clearly how they interpreted the text based on little knowledge versus the secondary reading, with thorough background information to give context. I know personally, for Sita's Ramayana, I came in knowing a few things gleaned from various movies and brief mentions in books. I read the work with very little background information, and afterwards researched the culture more extensively. I think, when I reread the work, I will have greater understanding of why Sita acted as she did in many instances. Even just this discussion has deepened my understanding on the cultural aspects of the work.

Arni, Samhita. Sita’s Ramayana. Berkeley, CA: Groundwood, 2011. Print.

- Kelsie

In response to Kelsie:

I was also intrigued by the introduction, “With its decidedly feminist perspective, Sita’s Ramayana highlights the tragedy that can result from disharmony between husband and wife and the painful consequences to women, children, and ordinary people when their lives are determined by competition between powerful men.” It says a lot about why Sita reacted the way she did to the heartache she endured. I can only imagine that in her shoes I would also feel defeated and I truly do not know how I would react. It is easy to say what we think we would do in a difficult situation, but truly we wouldn’t know until we are actually there. I agree with you Kelsie, perhaps Sita felt so worn out in the end that it was easy for her to walk away, even from her own sons. I had not thought of that originally and you helped me see a different point of view. Thank you!

Arni, Samhita. Sita’s Ramayana. Berkeley, CA: Groundwood, 2011. Print.

In response to Rachel:

Rachel, I agree with you about the story being very deep. I researched the story after originally reading Sita’s Ramayana but didn’t get around to researching the illustrator. Thank you for sharing your findings. I shared the story with one of my eighth grade teachers, a fan of graphic novels, and he loved it. This story makes for a good piece to use in an interdisciplinary unit. We are planning on using this book on a unit next school year and are midway our research. I will most definitely further research the illustrator and see if we can get the art teachers involved. I absolutely loved the illustrations! Such beautiful pieces of art!

Norma

Arni, Samhita. Sita’s Ramayana. Berkeley, CA: Groundwood, 2011. Print.

Norma, that's great that you will be using this in a unit! I look forward to further research as this blog session has brought forth many questions for me. For example, I want to find out not just what this means to those belonging to this culture but how its meaning differs among various types of people within the culture (i.e. elders, women, children, men, rich, poor, etc...). I would also like to research any comparable tales from other cultures (Dr. M mentions Tiger Moon in her post and I'm curious about others).

I'm grateful for the exposure to this particular version of Ramayana as my first experience with it, as I don't know how I would have responded to it had it not been the feminist version. I found the feminist perspective refreshing and enticing regardless of the cultural confusion I experienced with some of the pieces within.

Sita's Ramayana is not only an enjoyable read but also an eye opening piece of literature and I appreciate the fresh view this graphic novel gives young readers as not all ancient tales are as easily consumed.