Explore Imagination through Outstanding International Book Characters

Imagination in its many forms is present in much of children’s and young adult literature just as it is in "real" life. It can help us deal with situations that are seemingly beyond our control, express ourselves in authentic ways through other sign systems, create practical solutions to everyday needs or desires, position ourselves in other contexts as we work to understand other perspectives and eras and add an enjoyable fantasy element to our lives. I always enjoy revisiting the following quote: "Imagining possibilities is at the core of understanding other people, other times, and other places" (Wilhelm and Edmiston, 1998, p. 4). I also am reminded of Frank Smith's idea (1992) that imagination makes reality possible (1992). So, while there are many ways to celebrate imagination in children’s literature, I would like to share, from the 2019 (published in English in 2018) OIB list, a few very basic examples of children using imagination in seemingly simplistic ways. I believe that these are the seeds that can grow into more complex uses of imagination as children grow into creative and responsible adults.

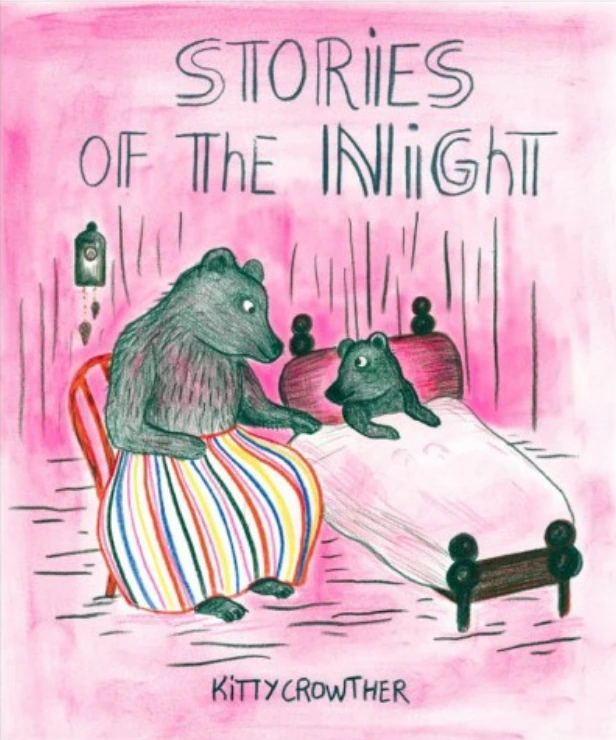

The first story that we will examine is Stories of the Night by Swedish award-winning author Kitty Crowther, translated by Julia Marshall. The story begins with a typical scenario of a mother reading stories- with a focus on personified animals- to her child at bedtime. The child is familiar with these stories, as he asks specifically for three tales: the Night Guardian, who puts all the young forest animals and herself to bed; a child lost in the woods, given shelter by her bat friend in his treetop nest; Bo, a little man in a huge overcoat, who goes swimming in the ocean fully dressed before he can go to sleep. Crowther provides vivid illustrations of each story told– presumably how the child might imagine the somewhat bizarre nature of each. However, the most typical imaginative moment comes at the end when the child is pictured with all three of the story characters in bed with him as he drifts into sleep. The imagined reality of his bedtime stories, told over and over, have provided imaginary bedtime friends. We know that the story worlds of children come alive as they negotiate between reality and play. Vygotsky reminded us of the importance of this play world and the imagination that serves as building blocks for the child’s social reality.

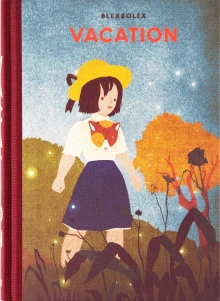

Another interesting story that utilizes imagination is Vacation, a story from France by Blexbolex. This wordless graphic book tells of a young girl who arrives at her grandfather’s home for the summer and finds he has brought in an elephant. The book uses detailed illustrations to share how the girl deals with this not-so-welcomed visitor – a visitor that she at times imagines to be a real boy intruding on her solitary visits to her grandfather’s. The reality of her actions reflect contemporary childhood, and there is much use of imagination, again reflecting reality, as the girl deals with the situation of coping with the houseguest. There is imagination in dream sequences as well. This book leaves much room for interpretation and for considering imaginative reactions to real situations, but it is also enjoyable for the visual depictions that have won awards for its creator.

We know that often times, imagination inspired by necessity, can fulfill personal needs and desires. Originally published in Australia, but set in a seemingly African village as implied in the author’s notes, The Patchwork Bike by Maxine Beneba Clarke and illustrated by Van Thanh Rudd, offers an enlightening example of purposeful imagination. Children in a seemingly poverty-stricken area at the edge of the "no go" desert in a house made of mud find great joy in their home-made bike constructed from a collection of items they have gathered, such as, a flour sack, milk pot, bark, tin cans and the “infamous” card board box. Their resourcefulness is realistic and they let no one interfere with their joyous rides, even their “fed up mom.” The story is told from the perspective of the main character –a daring young female with a strong sense of agency that is not imaginary but to me, her agency seems obviously enhanced by the imagination with which she and her brothers approach their play. The lyrical verse adds to the imaginative quality, as in "It has a bent bucket seat and handlebar branches that shicketty shake when we ride over sand hills." And, the author’s note at the end explains the story’s purpose and supports the reality of these children using their imagination in ways that enhances their lives.

Two books that I found quite impressive in how they revealed the imagination, though not considered OIB finalists, both focus on seaside contexts. The first,Stories in a Seashell written by Alex Nogués Otero of Spain and illustrated by Silvia Cabestany, begins in a very universal way. Young Max is playing on the seashore when he discovers a conch shell and wonders if it's "true that one could hear the sea inside." Putting the shell to his ear is the beginning of imagined scenes, typical of the sea and revealed to the reader through the muted pencil and paint illustrations. Max’s imagination is unlimited as the sounds he hears and images that reveal a continuous story of a pirate ship, a mermaid who surprised an old man in a paper boat, birds flapping wings in the sky, a whale singing its song, millions of jellyfish, and even a submarine captain looking through a periscope at a boy on the beach listening to a shell– bringing full circle the imagined images from the sea sounds of the conch. The potential of imagination through story and the communicative signs we use to understand the world, are brought together in a book that will make readers wonder at the potential sound the next time they hold a shell.

Imagination can keep memories alive. The second seaside themed book, Grains of Sandby Sibylle Delacroix, originally published in France, tells of 2 children who are sad to leave the sea after their family summer vacation. When the young girl finds sand in her shoe upon their arrival home, imagination sets in as she and her brother decide what to do with the grains. "Let’s plant them!" leads to imagined possibilities of a resulting field of beach umbrellas, a forest of pinwheels, a crop of lemon-flavored ice cream, a golden castle, or a beach. The illustrations are predominantly created in black and while pencil with a touch of blue paint for the clothing of each child and the obvious gold for the grains of sand and each imagined product from its "planting." The book closes with the dad’s promise to return the next summer to the beach.

One last favorite book emphasizes the role of imagination in considering the natural world. Anywhere Artist by Nikki Slade Robinson (2018) didn’t make the final list of OIB books, but is one that points to the significance of imagination as specifically acknowledged by the young girl who is the only character in the story. She proclaims herself an anywhere artist whether in the forest, at the beach, in the rain, or watching the sky. Using the natural products of each environment, she says she doesn’t need paint or paper – "My imagination is all I need." For example, in the forest, she finds "fluffy lichen, twisted sticks, smooth stones, and lacy leaf skeletons with which her imagination creates a lizard-looking creature. The illustrations are simple with emphasis on both the physically slight character and the findings within each simplified setting— resulting in her creation. Young readers can be directly inspired by the imagination of this young girl and might be encouraged to become an "anywhere artist."

The response of a reader to a book depends on the reader’s imagination that takes him or her beyond any parameters to unique transactions with texts. For young readers, having rich examples of the way imagination can take one beyond the ordinary, nurtures their creative and critical thinking to inform and transform their lives and ultimately their worlds.

Feel free to share favorite titles that address imagination and that might pair well with the newer titles shared here. Last week's issue of WOW Currents can be found here.

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m.