By Angelica Serrano, 4th Grade Teacher, Van Buskirk School, Tucson, Arizona

“Tú eres mi otro yo, si te hago daño a ti me hago daño a mí mismo; pero si te amo y respeto, me amo y me respeto yo”

“You are my other me, if I hurt you then I hurt myself too, but if I love you and respect you, then I love and respect myself too”

Award-winning playwright Luis Valdez’s poem captures a foundational teaching goal of mine, focused on reclaiming time for social emotional learning during my school day. Clearly the 2020 pandemic continues to impact children’s learning, including how children regulate their emotions and social interactions with others in the classroom. Over the past two years, teachers across the nation have expressed challenges they face through social media and other outlets. Many still see ripples of the pandemic as both students and teachers struggle to create spaces for learning, communication, cooperation, and community building.

Students and teachers alike are both challenged to create inviting spaces for thoughtful conversation around social emotional learning while at the same time maintaining academic success. With a nationwide scarcity of teachers and counselors, it seems impossible to keep up with all of the emotional and academic demands; at times it feels overwhelming. The good news is that educators and students can reclaim social emotional learning through children’s literature. Children’s literature provides educators and students with a vital opening for crucial conversations in these unique times. Therefore, it is imperative to seek out children’s literature that speaks to social emotional learning. Teachers need to set aside class time for introducing reading and writing and helping to instill communication strategies that encourage students to not only maneuver their emotions but to also create a space for building empathy and

kindness.

As a fourth-grade educator, I began a search for children’s books to help create spaces for students and me to generate safe and critical conversations. Since the beginning of the school year, I realized we needed opportunities to share emotions and

explore strategies to help support healthy ways of communicating with others. As educators know, building relationships is a vital step for both students and teachers. I found that when I took time to get to know my students, I could address their needs as well as learn from their experiences to modify and adjust my teaching. I Wish My Teacher Knew: How One Question Can Change Everything for Our Kids, was one professional text I recently used to ground my approach for welcoming students into our classroom. In 2016 Kyle Schwartz, a third-grade teacher, shared this activity with her students, which evolved into a viral movement known as #IWishMyTeacherKnew. Her student engagement helped reveal students’ heartfelt and heartbreaking insights.

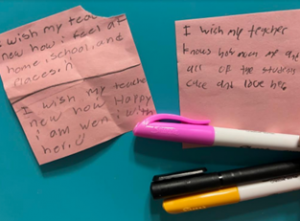

This last month in late November I realized the need to pose Schwartz’s question to my fourth graders. I began by asking students to write “I wish my teacher knew” on a post-it note. I asked them to complete the note anonymously. Next students were invited to place their post-it note in a box I left at the front of the room. As students jotted down their ideas, they asked me not to look or peek. Soon I began to hear small footsteps approaching the front of the room and papers slipping into our box. The room remained silent. I could feel the interest students had in sharing what they needed to say with me.

Shortly after, class was dismissed as we had completed the activity towards the end of the school day. As I sat down to read the notes, I discovered the most beautiful messages and even some heartbreaking ones. One student stated: “I wish my teacher knew that she makes me so happy and makes me feel safer than at home.” Others spoke of economic difficulties at home, particularly as the holidays approached. There were other responses focused on family separation or loss of loved ones and pets. I realized the humanity behind these messages, not just students that we prepare to take exams. Other notes spoke of love and feeling embraced at home and at school; there were others who shared insights into feeling bullied at school by other children.

The next day, students expressed interest in knowing how I felt reading their notes. They seemed to acknowledge the power of my social emotional learning process. All of them wanted to know what others wrote even though everything was anonymous. Students agreed to listen attentively and not make any comments as I read the notes aloud. The room was quiet and reading the notes a second time evoked tears, not just from me but from some students as well. We realized that others had shared their vulnerabilities, and it was through this vulnerability that students and I understood how we all go through similar emotions, losses, and experiences. Some were surprised to discover what their peers were going through, and they felt empathy for their classmates. “I never knew that we all are going through something,” a student stated as we looked around at each other.

Based on this initial experience I continued our collective work in December. Once we completed district mandatory exams in November, I sought support from our librarian and school counselor, hunting for strategies and children’s books to help support my students.

As we uncovered various texts, I made time to explore a few with my fourth graders. One of the first texts was The Circles All Around Us (Montague, 2021). Before I read aloud the text, I asked students to listen and think about what they were feeling at that moment as well as what they were seeing and learning. The concept of circles provided in this text was impactful not just to me but to students as well. During my childhood, I recalled learning about personal space using the concept of circles. I recall my teacher placing a hula-hoop around me, followed by this statement: “This is Angelica’s bubble.” What I took away from that lesson was that no one could be in my bubble and how too many people in my bubble could make me feel uncomfortable. At that time, my bubble or circle was small, and I was told by my teachers that it was a stagnant circle; it would never change. My current students had explored a similar lesson at the beginning of our school year regarding personal space, through a mandatory curriculum implemented by our school district. But, this text, The Circles All Around Us, allowed us to see that our circles can get bigger because we can share them with the people around us. In fact, our bigger circles can invite in friends, pets, family, community, and even people we don’t know yet.

Montague’s text invites us to create bigger circles while still maintaining our smaller circles. Circle over circle over circle. This concept reminds us that personal space is important. Yet inviting others into our spaces can create meaningful experiences as we move throughout our everyday lives.

I invited students to think about this concept. One of my students responded by asking for a moment to explain what she had learned to our entire class. She began by asking me for some string. I got a long piece of yarn and made a small circle around her.

She stated: “I feel lonely when I am just in my circle.” Another student said: “Yeah, like depressed.” “Yes!” the student responded. “But, when I make my circle bigger, I get to bring my friends in with me.” She asked me to make her circle bigger, so I cut another piece of yarn. I expanded her circle as she invited her closest friends in. The students giggled and she stated: “I feel better now.” Another student said, “I get it.”

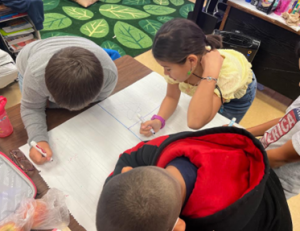

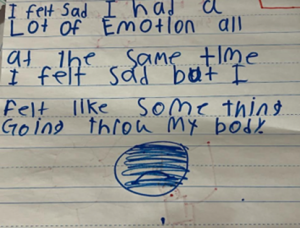

Our ensuing conversation focused on how it is okay to have our personal, little circle or personal space, but that always being alone can be difficult as well. “We need friends to talk to about our feelings,” another student said. Then I invited students to participate in a graffiti board activity (Short) This reading response strategy invites students to write how they feel or to draw symbols, thereby expressing their reactions to the text and the subsequent class discussions.

Fourth graders thoughtfully engaged in writing their thoughts down and were also given the space to share their writing or drawings with each other. “I felt petrified,” one student explained. The students looked at each other and one asked: “Why?” “I just feel petrified because I didn’t know that someone in our class is having a rough time at home.” The students acknowledged each other’s responses in small groups and continued their sharing time.

As I walked amongst the groups in our room, I noticed similar emotions and responses. One theme was consistent: “I feel sad for so and so and it reminds me of…” I began thinking about the importance of empathy and kindness. It was evident students were starting to think about each other and each other’s emotions.

In my next January blog, I continue to share texts, critical conversations and activities I used with my fourth graders throughout December. I realized I need to find more time for social emotional learning, revealed by fourth graders’ honest comments and their growing awareness of others’ needs and concerns.

Reference

Schwartz, K. (2016). I Wish My Teacher Knew: How One Question Can Change Everything for Our Kids. Da Capo Lifelong Books. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wq25mQdly28

WOW Currents is a space to talk about forward-thinking trends in global children’s and adolescent literature and how we use that literature with students. “Currents” is a play on words for trends and timeliness and the way we talk about social media. We encourage you to participate by leaving comments and sharing this post with your peers. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit its archival stream.

- Themes: Angelica Serrano, Circles All Around Us, I Wish My Teacher Knew, Kyle Schwartz, Montague

- Descriptors: Student Connections, WOW Currents

Angelica, I agree that we need more respectful interactions in these polarizing times. Reclaiming time for SEL in the midst of “supposed” learning loss is key. Children deserve more than test-driven and textbook-focused educators. They deserve teachers like you who respect them and their unique funds of knowledge. Thank you for urging us forward. Charlene