It’s like we’re in the book, Miss! A Multimodal View of Self (and Others) through Connections, Color and a Cross-Cultural Lens

Nalda Y. Francisco and Kathryn Chavez

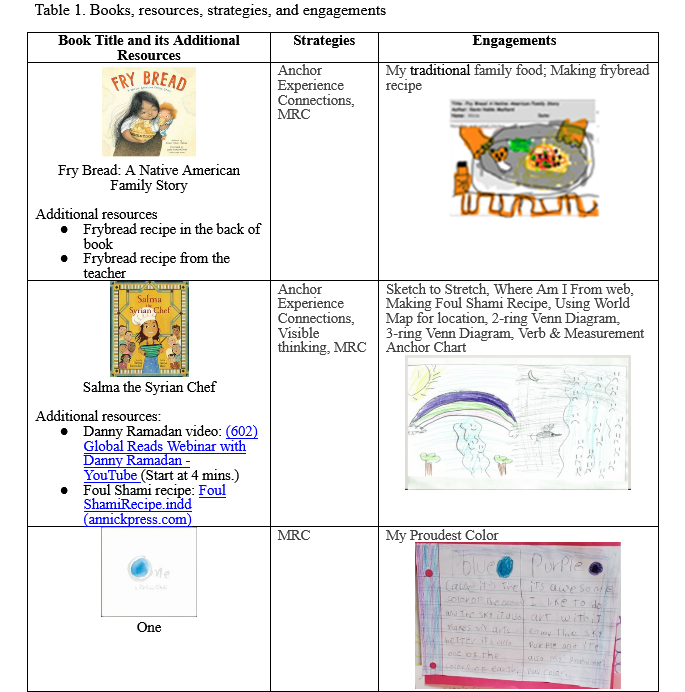

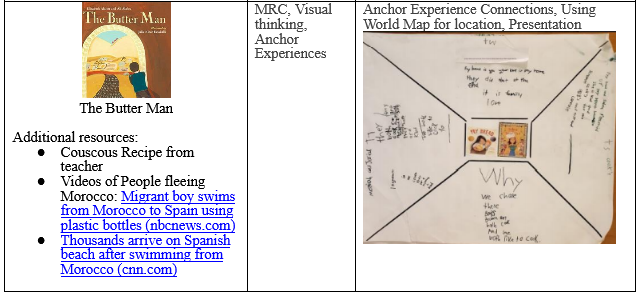

This article describes the literacy experiences of a third-grade teacher, Nalda Francisco, an instructional coach, Kathryn Chavez, and the students who together embarked on a multicultural literature journey. The study group was comprised of thirteen students who self-selected to return to in-person learning when Covid-19 pandemic restrictions were lessened. The research site is a K-8 school in an urban city area located in the desert Southwest. Four of the thirteen participants were second graders who joined the 90-minute third-grade literacy block each morning due to overcrowding in their second-grade in-person classroom. Eighty-five percent of the class are classified as Latinx students, plus one African American and 1 multi-racial student. Framed in the belief that critical literacy, reading both the word and the world, are important components of any curriculum (Freire, 1989), the engagements were designed to explore students’ own cultural experiences as well as a range of cultural perspectives other than their own. The instructors, members of the Southern Arizona Global Literacy Community, also drew from the social practice of making meaning by combining multiple multimodal representations to represent the knowing and learning taking place in the classroom. Nalda and Kathryn were anxious to create and implement an engaging and informative unit to students returning from remote learning.

The 8-week unit was designed to support students at varying grade levels to read about, examine, and reflect upon the family traditions, food, and experiences of characters in a variety of multicultural books. The idea was for students to connect literary experiences to themselves, their teachers and classmates as they explored cultures similar to and different from their own. At the end of the unit, we wanted students to create a montage of their work and present their two favorite books. Nalda wanted students to talk about and connect books on their own without a teacher-led discussion. She made sure the presentation included connections between the two books and an explanation of why those two books resonated with the presenters. For Kathryn it was important to use multimodality as a strategy for deeper understanding rather than an embellishment or frill.

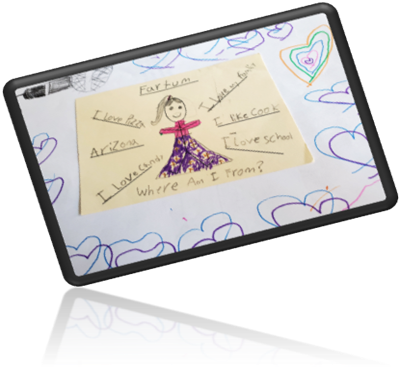

The text set was comprised of eight books reflecting a range of global perspectives, including Middle Eastern, Southwestern, and Indigenous cultures. Two of these books served as anchor texts and were referred to throughout the eight weeks. The unit was framed around the enduring understanding: Across time and cultures there is more that connects than separates us. The essential question used to frame the lessons was: Where Am I From? The question was not only directed towards students, but also used to examine main characters. Other essential questions emerged dependent upon the text set selection (e. g. Do you think the cat man from Aleppo is a real or a fictional character?). Along the way two additional books were incorporated to serve as a scaffold and provide students with a deeper understanding of visual representation and use of color as they explored their own cultures and cultures other than their own. In the end, connections and inferences were made through student-led discussion rather than teacher led.

Strategies: Making Connections and Beyond

Great books are key to teaching reading comprehension (Harvey & Goudvis, 2000). Students in Nalda’s class were not only immersed in great literature, but they were also immersed in great reading and thinking strategies. While background knowledge and experiences come to mind as one reads, deeper comprehension comes from linking those connections to our lives (text to self, TS), other books (text to text, TT) and the world (text to world, TW). Other ways of linking experiences were taught using two anchor texts to build schema. Strategies included:

- Anchor experiences (e.g., reading and re-reading anchor texts, traditional food and recipes, exploring maps, TS, TT, TW connections, sketch to stretch, book cover analysis)

- Visible Thinking graphic organizer use (Venn diagrams, KWL Charts, Character webs, Color my world notetaker)

- Multimodal response competency-MRC (embodied representations: patterns, recipes, proudest color)

Nalda and Kathryn modeled these comprehension strategies in diverse ways with different books (see Table 1), and then gave students opportunities to discuss and practice in small groups–and eventually take ownership of using the strategies at the appropriate time and place.

Connecting Anchor Texts and Experiences

The two books used to anchor and connect readers’ experiences throughout the unit were:

- Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story, written by Kevin Nobel Maillard, & illustrated by Juana Martinez Neal (2019, Roaring Brook Press)

- Salma the Syrian Chef, written by Danny Ramadan, & illustrated by Anna Bron (2020, Annick Press)

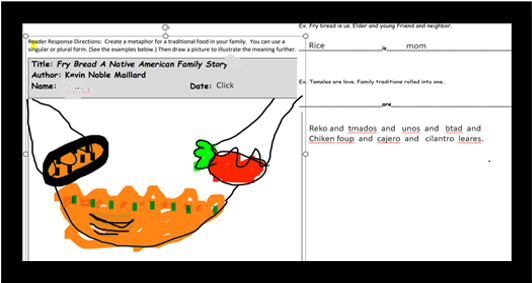

Traditional foods were linked to the two anchor texts to serve as a foundation for student experiences. These anchor experiences were then used to connect, compare and stretch students’ thinking as they explored the entire text set. Most of the third graders in Nalda’s class had participated in the WOW Center’s author/illustrator presentation of Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story (2020) while attending school remotely. After returning to in-person learning, students read the story again and were given an assignment to create powerpoint slides of a traditional food they ate with family. Whether they ate pizza on a particular night of the week or made a specific dish for family gatherings, the important idea was connecting food to family. Once drawings were complete, Nalda used examples from the text to have students create metaphors representing their family food. Students later returned to these initial pictures to add instructions for their recipes and as a reference when writing their own self-recipes (see Figure 3).

Salma the Syrian Chef served as the second anchor text. First the book cover was analyzed closely as a pre-reading strategy to point out use of color and patterns and to make predictions.

David: Cooking book, she has a cooking hat.

Fatima: She’s cooking for a family.

Joe: Cooking for a restaurant.

Jose: A chef.

Roy: People love her food because their smiling.

Mario: The girl is smiling too. She’s happy! She’s a cook. She likes to cook.

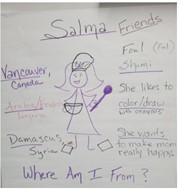

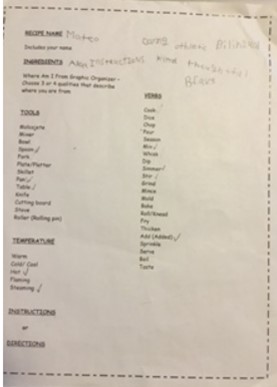

After the first reading, a Where Am I From character web was created for Salma (see Figure 4). Maps were also used to help students contextualize location and distance (see Figure 3). After the second reading, students watched a video of the author, Danny Ramaden, making Foul Shami–a Middle Eastern dish central to the book. Next, the class made Foul Shami and the following day from their printed recipes, brainstormed a Verbs and Measurement anchor chart that would serve as a reference when creating their own self recipes later in the unit. Students also considered Salma’s use of color in her drawings and realized that Salma’s favorite color was purple. In turn they revealed their own favorite colors in a journal response format (see Figure 4).

Next, students explored a visualization strategy–Sketch to Stretch (Short, 1996)–in order to think more deeply about the author’s particular word choice (see Figure 5). Two quotes were selected from the reading and students were asked to create a visual representation for the quotes. Music was played during creation time and afterwards students presented their drawings to a partner.

After the third reading, students created their own Where Am I From webs and focused on their own favorite color selected previously (see Figure 6). The color was then incorporated into a representative pattern. The goal toward deeper understanding and student-centered discussions was set into motion.

Multimodal Response Competency-MRC

Multimodal representational competency (Yore & Hand, 2010) can help students arrive at deeper understandings as they learn to interpret and produce multimodal texts. Color connections, patterns and representations were introduced through anchor texts and focused upon throughout the unit. Siegel (1995) explains, “translating meanings from one sign system to another increases students’ opportunities to engage in generative and reflective thinking because students must invent connections between the two sign systems” (p. 455). Students considered and selected their own proudest color just as authors and illustrators use color to represent characters in the books they read. Besides their initial selection of a favorite color, participants learned to use color to express emotions and depict the metaphors and similes of authors. Students also used specific colors to represent themselves and members of their families.

Golden Domes and Silver Lanterns: A Muslim Book of Colors, The Proudest Blue: A Story of Hijab and Family, and Green as a Chile Pepper were used to bring about this result. Using a graphic organizer we named Color My World, students used examples from the books to create family representations based on color (see Figure 7). For example, in the Muslim culture blue was connected to the hijab the narrator’s mother wore and in Latinx culture blue was associated with the endless sky. Jose, a second grader, selected blue to represent his father because the color and his father both made him happy. His color selection was not random. He selected blue as his favorite color when relating himself to Salma in an earlier journal entry. Jose extended this thinking to his sister’s color representation of pink because it is her favorite color.

Another way multimodal representations were made was through food. In Golden Domes and Silver Lanterns: A Muslim Book of Colors, brown is associated with dates. After reading the book, students sampled and discussed the taste of the dates. While Salma did not relate a color to the dish Foul Shami, the ingredients were related to colors. Like two of Nalda’s students, the main character was a second language learner and she used color and drawing to communicate the ingredients she needed to make the dish for her mother (e. g. green for sage, brown for beans, white for garlic, etc.). Later in the unit, salsa was made in a molcajete as students listened to poetry choices from Salsa: A Cooking Poem (2017) and then sampled chips and salsa. This book served as a scaffold as red took on the form and taste of a food many students were familiar with and could relate to. Students also explored more vocabulary for recipe writing such as dice, chop, whisk, etc. (see Table 1) as they added more terms to the anchor chart of Verbs and Measurements that originated from their work with Salma’s Foul Shami recipe. The anchor chart was referred to again later in the unit as they wrote self-recipes and demonstrated multimodal representation competency by tying their traditional foods to themselves using traits and ingredients such as bravery, kindness, love, athleticism, etc. in the form of a recipe.

Visible Thinking Strategies

Besides the Color My World graphic organizer and the Where Am I From character webs used to help build multimodal representations competency, several other visible thinking strategies (e. g. Venn diagrams, KWL charts, journal writing, etc.) were used to deepen student understanding. First, a 2-ring Venn diagram was used to compare Salma, the Syrian Chef with the main character of Golden Domes and Silver Lanterns. The similarities students noted:

- The main characters were both female.

- Purple was each character’s favorite color.

- Color was tied to something valued. (e. g. yellow: the roof of a Syrian home & an Eid gift box)

At this point, the instructors still felt they were driving the conversations and wanted more student-led conversations. Kathryn decided to set the stage for the topic of bullying, which arises in The Proudest Blue: The Story of Hijab and Family, and help students consider their proudest colors. So, she selected the book One (2008) by Kathryn Otoshi as a scaffold. In this book, colors took on new meaning. For instance, the color red, a bully, tells the group of other colors that “red is hot, and blue is not.” Blue feels sad and wants to belong, but her peers are afraid of red and offer no help. This is a much different tone from the next book, The Proudest Blue, in which Faizah is empowered by her sister’s choice of blue for the hijab she wears proudly despite the taunting of bullies.

Note how in Figure 8 using Sketch to Stretch (Short, 1996), Alex uses red to represent the bullies and blue/green to represent Faizah’s sister standing up to them in his favorite scene of The Proudest Blue.

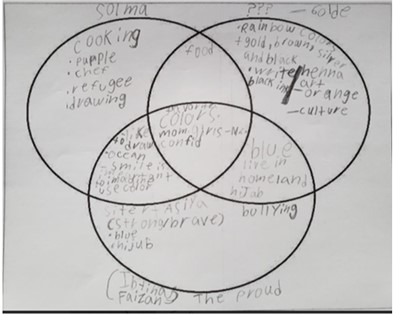

In a follow-up engagement after reading the three books, The Proudest Blue, the anchor text, Salma, the Syrian Chef, and Golden Domes and Silver Lanterns, a 3-ring Venn diagram was used in order to make comparisons between the three books (see Figure 9). The similarities students noted:

- the main characters were all confident girls

- all three main characters had a favorite color

- all three characters had a supportive family

- “Moms” were important all three books

Nalda sensed her students had unanswered questions concerning the hijab. She selected Under My Hijab to help students clarify their understanding. A KWL Chart (What I Know, Want to Know and What I Learned) provided students and teachers with insights into student thinking. Most students knew the hijab was something protective worn by women. Many students still wondered why women wore them and if wearing the hijab made you hotter. In the end they learned the hijab is taken off at home, worn for religious purposes, and comes in many colors. Students also realized that hair styles and colors underneath the hijab differ from person to person. Once students had a solid understanding of what the hijab was, its purpose and what it represented, it was time to move on to the two final books and give students an opportunity to blend the strategies.

Multiple Responses: A Blending of Strategies

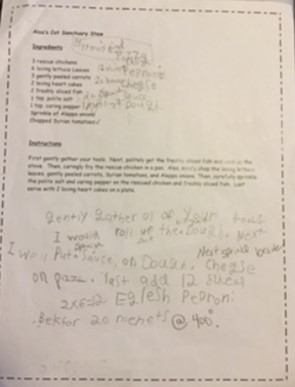

After reading The Cat Man from Aleppo, a character web of the main character, Alaa, was constructed. Once the character web was co-created with students, more connections were mad, and schema built using a YouTube video. Students discovered Alaa was not a fictional character but rather a real person who rescued cats in war-torn Syria –a place that Salma, the Syrian Chef, had once lived. This connection was made by students as they referred to one of the anchor texts and a character, Salma, for whom they had created a similar character web. Next, a recipe for Alaa was constructed using character traits from the character web and the recipe anchor chart. This was a difficult stretch for the group and both instructors recognized their struggle. For students to move forward in writing their own recipes, a graphic organizer was designed that incorporated the main components of a recipe from the anchor chart and a mentor text of the Alaa’s Cat Sanctuary Stew the group had co-written (see Figure 10).

Once students created a rough draft of their self-recipes, instructors helped edit and gave feedback. Then revisions were made, a revised draft was typed by students using a recipe format and clipart selected to depict a deeper meaning of the text. The final products provided the instructors with a means of assessing the students’ overall multimodal representational competency. Due to absenteeism, eleven of the thirteen students completed the assignment and all eleven students demonstrated competency in translating one sign system to another (see Figure 11).

The Butter Man (Letts, Alalou, & Essakalli, 2008) was selected by Nalda and Kathryn as the final book for the unit. The book is rich with color, art and conceptual meaning. Couscous, the traditional Moroccan dish referred to in the text, provided one more opportunity to link a traditional food to the students’ schema. In addition, Nalda and Kathryn noted student-centered discussions made insightful connections without teacher direction. Students made predictions about the book as follows:

Jose: Maybe they didn’t have food. Maybe they made a butter man.

Alex: The whole land looks like butter.

Jose: The picture of where the little boy lives. (Connection with the Gingerbread man)

Alex: The boy’s name is “Ali” in the story. In Cat Man of Aleppo, the man’s name is “Alaa”.

Max: The butter man is someone who walks around and gives butter to people.

Joe: On the first page, the view is higher above the land and now the view is closer. It looks like a path.

Joe: Dad is the butter man and he left.

The book also provided a salient link to contemporary issues in the news as students watched a current news clip on Moroccan migrants fleeing to Spain by swimming with plastic water bottles attached to their bodies (see Table 1 above for link). The instructors posed the question to students: Why do people flee their home country? This inspired more free-flowing dialogue in which students offered answers such as hunger, food, water, work and survival as possible answers. The dialogue also provided an opportunity for them to consider why Ali’s father left to work elsewhere and why Alaa had chosen not to flee Aleppo when the war began.

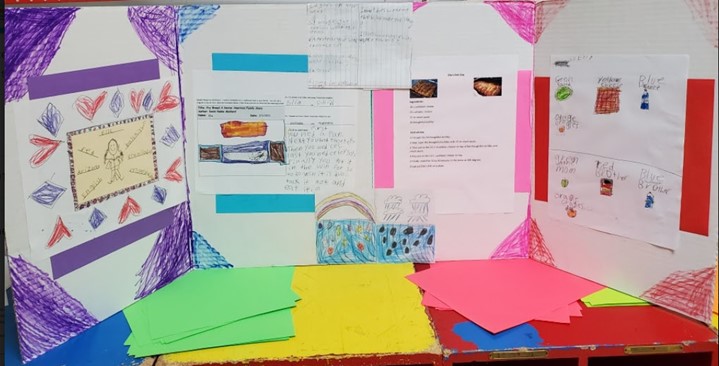

It was now time for students to demonstrate their multimodal representational competency on their own. Students were given a display board on which to draw a representational pattern around the edge and to affix their work from the unit in a montage (see Figure 12). Some chose to work together and some alone, but students were engaged and eager to display their hard work. Display boards were sent home with students to share with family and friends. Adding to the festive atmosphere, Nalda and her sister set up a cookstove outside and heated hot oil to make fry bread for the students who each rolled out the dough to be cooked. Once back in the classroom, Nalda shared her traditional recipe of Navajo tacos with students and provided the ingredients for each child to make their very own taco. It was just like we were in the book!

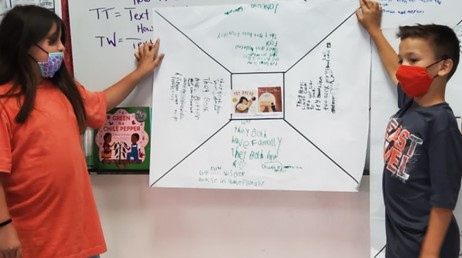

For their culminating project, students considered the enduring understanding: Across time and cultures there is more that connects than separates us, as they selected two of their favorite books to present to the class while explaining their text to self, text to text, and text to world connections. They also answered the question of why those two books mattered and even continued making connections during the presentations. Hope and Jose selected the anchor text Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story and the final book they read, The Butter Man, to relate (see Figure 13). The two students both liked to cook and found family to be an important text to self-connection. Cooking as a family was central in both books – something both students valued and felt connected cultures. Interestingly one group, Joe and Moses, selected the two anchor texts to compare (see Table 1). Like Hope and Jose, they were drawn to cooking and family; they noted bowls on both book covers and related food to family, which had been the springboard for the unit. Joe and Moses also made connections and noted the yellow color on the cover was similar, one representing butter and the other bread.

“You, know…Taco Tuesday. It’s everywhere!” Max exclaimed during his final presentation when he made text-to-world connections beyond the two books he and his partner, Eve, selected to compare. The partners both liked chips and salsa and were drawn to the books because they “went together.” While presenting their “Taco Tuesday” text to world connection, as Max spoke his eyes lit up. The books, Green as a Chile Pepper: A Book of Colors and Salsa: A Cooking Poem, took on new meaning for Max as he made deeper world connections beyond the books by realizing the significance of tacos and how the food relates to everyday life in his southwest community and beyond the Mexican border. Max took ownership of the comprehension strategies introduced while we were reading a series of strategically selected multicultural books and in the end, linked the texts to himself, his classmates and beyond.

Nalda’s Final Reflection

During this global and multicultural literacy journey, students had many struggles and ah-ha moments throughout the unit. Many were able to connect to the characters and books in multiple ways. Some students could see themselves in the stories, such as Fatima’s connections to The Golden Dome and Silver Lanterns: “My dad wears one of these.” “This is my life story.” “Henna, remember when I had markings.” We even saw some students come out of their shells and participate more in class discussions and they were more willing to share their culture and family traditions. At the beginning of the unit, it was a struggle for many to participate and share their ideas in the class discussion, but over time more students were willing to participate and share. The atmosphere of the classroom changed from being teacher led to student led.

At the beginning of the unit and during the first couple books, we had to develop and ask questions throughout the reading of stories to get students involved. But as students became comfortable and more engaged in the stories, they started to ask questions and have mini discussions about different aspects of the stories as the book was read aloud in the class. They asked each other questions and some students had mini conversations with their neighbors about things they noticed or wondered about in the stories. An example of these student-led discussions occured when reading The Butter Man.

Joe: What does fragrant mean?

Hope: Food you smell. It makes the house smell like the food.

Max: Baba is making the food in the kitchen.

The classroom atmosphere slowly changed from the teacher asking questions to the students asking each other questions or having mini discussions about different aspects of the story while the teacher facilitated the discussion. Everyone who wanted to share was able to before moving on to the next part of the story. It was exciting to hear these conversations and discussions. Students were making connections and using reading strategies they had learned over the last couple of years.

Looking forward to the upcoming year and repeating this unit, students learned a lot throughout the unit and had questions or wonders about different aspects of the stories and how they related to their lives and communities. For instance, a student made a comment about the school cafeteria food and how we could make the food better or more edible. Next year, I would like students to create a project with a problem they have found in their lives or community and try to find a solution or ways to improve the situation.

Kathryn’s Final Reflection

Students were given opportunities to think critically to “understand their current lives and imagine beyond themselves” (Short, 2009, p. 7). While the curriculum standards were addressed in the unit, the learning went much deeper as students explored food, feelings, thinking and lives of other cultures using multicultural and global literature. No doubt students were happy to be back together after pandemic restrictions had been lifted. It was a special time and a much-needed way to explore cultures other than our own. This unit is also an extraordinary example of how multimodality can be used in the classroom as a strategy rather than an additive. Along with multimodal representations, children learned to use and take ownership of comprehension strategies in engaging ways. Oftentimes we would look at the clock and realize it was already time to go to lunch. The enthusiasm and engagement along with the multimodal representations that students created during this memorable time were remarkable. I am excited to embark upon our next journey as Nalda and I set out to include others willing to imagine beyond themselves and the confines of teaching in these skills-based times.

Children’s Literature Cited

Argueta, J. (2015). Salsa: Un poema para cocinar/ A cooking poem. Illus. D. Tonatiuh. Toronto: Groundwood Books.

Khan H. (2019). Under my hijab. Illus. A. Jaleel. New York: Lee & Low Books.

Khan, H. (2012). Golden domes and silver lanterns: A Muslim book of colors. Illus. M. Amini. San Francisco: Chronicle.

Letts, E., & Alalou, A. (2008). The butter man. Illus. K. J. Essakalli. Watertown, MA: Charlesbridge.

Maillard, K. N. (2019). Fry bread: a Native American family story. Illus. J. Martinez-Neal. New York: Roaring Book Press.

Muhammad, I., & Ali, S. K. (2020). The proudest blue: A story of hijab and family. Illus. H. Aly. New York: Little, Brown.

Otoshi, K. (2008). One. San Rafael, CA: KO Kids Books.

Ramadan, A. D. (2020) Salma the Syrian chef. Illus. A. Bron. Toronto: Annick Press.

Shamsi-Basha, K., & Latham, I. (2020). The cat man of Aleppo. Illus. Y. Shimizu. New York: Putnam.

Thong, R. G. (2016). Green is a chile pepper: A book of colors. Illus. J. Parra. San Francisco: Chronicle.

References

Harvey, S., & Goudvis, A. (2000). Strategies that work: Teaching comprehension to enhance understanding. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Siegel, M. (1995). More than words: The generative power of transmediation for learning. Canadian Journal of Education, 20, 455–475.

Short, K. G. (2009). Critically reading the word and the world: Building intercultural understanding through literature. Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature, 47(2) 1-10.

Short, K. G., & Harste, J. C. (1996). Creating classrooms for authors and inquirers (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Yore, L. D., & Hand, B. (2010). Epilogue: Plotting a research agenda for multiple representations, multiple modality, and multimodal representational competency. Research in Science Education, 40, 291-314.

Kathryn Chavez is a Curriculum Service Provider at Safford K-8 School.

Nalda Francisco teaches third grade at Safford K-8 School.

© 2021 by Nalda Y. Francisco and Kathryn Chavez

WOW Stories, Volume IX, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work by Nalda Y. Francisco and Kathryn Chavez at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/volume-ix-issue-2/9/.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551