By Marie LeJeune, Ph.D. & Tracy Smiles, Ph.D., Western Oregon University

Last week we presented a framework that, as we said, “reflects a mixture of our past experiences as literacy teachers, teacher researchers, and teacher educators, and our current perspectives on literary and pedagogical theories and how they might play out in practice.” We will use this framework to describe and reflect on some of those experiences in K-12 classrooms. Our framework revolves around three main aspects of the literacy invitation — the texts we choose, the literary theories we employ and ground our work within, and the actual pedagogical strategies and methods we engage in with students.

We also discussed how important it is for teachers and researchers to claim a theoretical framework that guides their work — this week’s blog focuses on Marie’s past work with 9th grade students at a time when she was first beginning to grapple with and attempt to adopt tenets of critical literacy within her own classroom practice and pedagogy. Marie was preparing to teach Farewell to Manzanar (Houston, 1973), a required text for the 9th grade students at the high school where she was teaching, and wanted to approach issues of multiple perspectives and issues and concerns related to impacts of war. A recent graduate course in critical literacy had inspired her to more fully embrace texts that offered possibilities for deconstructing issues of social justice and equity. At the same time, she was deeply grounded in her beliefs in the importance of response based pedagogy — of honoring the responses and experiences of individual readers (Rosenblatt, 1938).

THE INVITATION

THE THEORY: Critical Literacy and Reader Response Theory. Specifically, Marie drew upon the work of Lewison, Flint & Van Sluys (2002) as she defined a critical approach for her classroom and began designing response and writing prompts:

-

- Disrupting the commonplace

- Interrogating multiple viewpoints

- Focusing on socio-political issues

- Taking action and promoting social justice

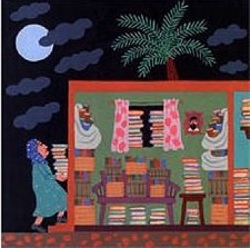

THE TEXTS: Marie read aloud two sophisticated picture books to her students, something that was a regular part of her classroom practice (the use of read-a-louds and the sharing of picture books suitable for secondary study). Focusing on the theme of the multiple impacts of war on people, she carefully chose The Librarian of Basra (Winter, 2005) and The Faithful Elephants (Tsuchiya, 1988) as her two read-a-louds selections. Both books consider an unexpected consequence of war and its impact upon society — The Librarian of Basra discusses how Alia Muhammad Baker rescues the majority of the Basra library from bombings despite being told by the government not to; The Faithful Elephants describes the extermination of animals at the Tokyo zoo during World War II.

THE PEDAGOGY: Rather than impose questions that directly dealt with the critical framework first with students, Marie decided to approach the stories initially from a response based perspective, which her students were more familiar with from former literature-based discussions. She calls this, “Beginning with ‘I’,” meaning students first respond about a personal reaction or interpretation of the story. This allows herself as a teacher and students themselves, to see where they “stand” on an issue and also values the individual perspectives of students as members of the literacy community. She starts with open ended prompts such as:

- What emotional reactions do you have to the story, the characters, the events, etc? Consider writing about something that made you happy, sad, angry, etc.

- What connections do you have to the story? Does it remind you of something that happened to you? Something else you read? Something you saw somewhere else?

- What questions are you left with? What do you want to know? What don’t you understand?

After providing time for students’ own written response, she also encouraged them to take a more critical stance on the texts, asking questions such as:

- Are there perspectives in this story that surprise you?

- Are there voices heard in this story that you might normally not hear in a story about war?

- Whose voices aren’t here?

- What does this story say about the issues of war and its costs?

- What might this story suggest about the issue of taking action?

MEDIATION: Marie’s students shared their responses in small groups and as a whole class. The responses revealed rich and thoughtful written and verbal reflections. A few excerpts from some of the students’ responses included:

- “I like that this story shows the perspective of a librarian and the love for her books. Usually in the war, people don’t stop to view other people’s positions in the situation. It shows that everyone has something they love that they could lose in a war. An alternative ending could be the end of the war, but sadly that’s no the reality of life. Alia shows how it’s important to have strength and hope, even during the war.“ Ariel

- “The librarian was very caring, responsible and unselfish. She did not save these books for herself, she saved them for generations to come. She risked her life for something important to her. This is different for a “war story,” because usually you read about politics and weapons, not books and libraries.” Katie

-

- ”This story opens your mind to thinking about what is really going on during a war. Not just the headlines—but the everyday lives of people.” James

- “This book gives voices to the elephants’ story. If it weren’t for this book, who would know this story other than the zookeepers? It’s important to know this and to think about the costs of war.” Ruben

- “This author shows how writing and books are so important. The elephants have no voice, the zookeepers were civilians the government wouldn’t listen to, but through the author’s writing, people will know their story. The author can show a perspective we might never have heard in history. It’s important to hear as many voices from history as we can to really know what the full history of any situation or any war is.” Anum

While these are just a few examples, most student responses contained some element of a critical stance in their interpretation of the story. Marie was excited to see the 9th graders consider issues such as whose stories are normally shared and whose are not, the value of considering multiple perspectives, and issues of how books and stories can be a powerful way to encourage social justice and to represent history more fully. However, when she collected students’ written responses to the two picture books, she also noticed several comments such as:

- “Saving books is a waste; I mean how important is that in the big picture of a war?”

- “I think this librarian was stupid to risk her life for some books,” etc.

These responses prompted Marie to wonder how many of the students that had written more “critical” responses actually took on that critical lens themselves and how many might simply be “performing” in a way they felt their teacher was demanding or asking of them. At that point, Marie considered her tensions with her role as a teacher in promoting a critical stance — how do we both honor individual readers while also attempting to “nudge” them to a more critical stance on the world and social justice issues?

PERSPECTIVES ON CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE PRACTICE AND REFLECTION:

This tension is one that we both still mediate and grapple with as we work with students of all ages as we both have continued our work on developing critical stance with children, young adults and college students; yet as we embrace our tensions we also still have many professional wonderings about the conflicting agendas that often exist within a classroom space. So we pose these questions to ourselves — and to you:

- How, as teachers, do we position our students and texts in light of our personal agendas and theoretical frameworks?

- How do we both honor individual response and encourage a critical stance?

- What influence do our personal and social histories and perspectives have on what we believe and value in relation to how we listen to and evaluate students’ responses to and participation with the texts and engagements?

We titled this month of Mondays “Invitation and Negotiation” to reflect our belief that we need others to think and inquire with us in order to sustain us as learners and educators (Short & Burke, 1991). This month we invite you to reflect on and share what informs your choices as teachers and teacher educators in the texts you choose to share with students, your agendas for doing so, and the challenges you’ve faced and the tensions you continue to grapple with.

Houston, J. (1973). Farewell to Manzanar. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Lewison, M., Flint, A., & Van Sluys, K. (2002). Taking on critical literacy: The journey of Newcomers and Novices. Language Arts, 79(5), 382-392.

Rosenblatt, L. (1938). Literature as Exploration New York: Modern Language Association of America.

Short, K. & Burke, C. (1991). Creating curriculum: Teachers and Students as a Community of Learners. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Tsuchiya, Y. (1988). The Faithful Elephants: A True Story of People, Animals and War. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Winter, J. (2005). The Librarian of Basra: A True Story from Iraq. New York: Harcourt.

Moje, E. (2002). Re-framing Adolescent Literacy Research for New-times: Studying Youth as a Resource. Reading Research and Instruction, 41, 211-228.

Short, K. & Burke, C. (1991). Creating Curriculum: Teachers and Students as a Community of Learners. Portmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m.

- Themes: Faithful Elephants, Jeanette Winter, Librarian of Basra, Marie LeJeune, Tracy Smiles, Yukio Tsuchiya

- Descriptors: Debates & Trends, Student Connections, WOW Currents

‘I’ is the best place to start in most new endeavors. Most readers respond to the ‘text to self’ as their first connection. But at least they are thinking about and extending the text beyond the words written … if only just a little bit.

I love the writing prompts given to the students and the philosophy of “beginning with I!” To start with connections to self validates students’ personal experiences and gives meaning to the task you asked of them. The responses from the students are inspiring too. Having not read “The Faithful Elephants,” I plan to check it out.

It would be interesting to view the misconceptions and media fueled interpretations of war that students are presented with in this society. One way to perhaps deconstruct feelings and interactions students have with these sort of “big issue” concepts is to do a pre-write on each concept – what are the kids thinking about when they hear a word (such as “war”)? What do they see, hear, think, feel about the concept and how does it relate to their life? This brainstorming activity still connects the concept back to themselves, the egocentric “I”, by exploring their knowledge and perception of the word. After reading a higher level picture book – could they take what they’ve previously written and share how their perceptions has been altered or grown given this new perspective?

I often times wonder whether students are performing, or “playing at” school, when we ask them to respond in an open ended manner about a critical issue. Frequently they have never thought about the concepts or ideas presented in these picture books (for example, the plight of elephants during war or the future of a library in a war torn city). First blush thought are rarely critical ones. It would be interesting to observe and note threads of critical thinking through blogs, journal entries as well as major writing assignments. M*A

I think the tension of honoring voices and moving toward a critical stance is really important. If we are considering the identities of students and their race/ethnicity, language, and social class, how do we as educators push/nudge our students to see outside of inside and outside of their circle. And then there is the question of authenticity? Are students trying to find the right responses or are they extending their thinking? I appreciate the framework that is used and how you are framing the texts. I think that we also need to consider how we can get students to see the positioning in the texts. I keep thinking about the critical and if I as the teacher get to decide what is critical in terms of response….