by Ann Parker, Pima Community College, Tucson, Arizona

I realized that the lowlands were always given to the poor, so naturally the Ninth Ward would flood.

“I’ll tell you what happened to me, but you have to promise never to use my name.”

. . . Kristallnacht was a blink in time . . .

Today’s blog continues the discussion between authors Ruta Sepetys, Jim Deem, and Jewell Parker Rhodes at the 2012 Tucson Festival of Books in March entitled “Confronting Difficult Life Events through Story.”

Q. What kind of research was involved in writing your book and how did you conduct your research?

Jim: I went to Auschwitz for one day, and I walked the whole place. I had already read about Auschwitz my whole life, but since I had to select 10 people [to focus on] I had to be intelligent in my choices, because I had to tell the story in a sequence and whoever was first had to tell the beginning of Auschwitz. The first person I started with was the Commandant [Rudolf Hoss], who set up the camp and was the first person to use Zyklon B [gas]. As far as researching Kristallnacht, since most of the people who lived through it are dead or very old, in their 90’s, I made the conscious decision not to interview many people. I’d interviewed people in the past for other books, but when people get very old, especially with a very difficult subject, it’s very cathartic for me and for them but it doesn’t add a lot to my research, so I stuck to published accounts. The problem was Kristallnacht was a blink in time, and people who wrote about their experiences in the war or the concentration camps spent one paragraph talking about Kristallnacht, and if they were very young they didn’t have many memories about it. I had to really hunt, to dig, to find my material. But I was very happy with what I came up with.

Jewell: I began researching as a junior in college and I was trying to write my first tale, and I got a Creole cookbook and it mentioned Marie Laveau, a voodoo queen from the 19th century. I’m always looking for passionate connections between me and a subject, I always write what I intensely care about, and I have been on this journey with Marie Laveau ever since. As I wrote [about her and Louisiana], I started to understand that in spite of The Great Depression, in spite of poverty or discrimination, you find the strength within yourself to say, “I am somebody” and to be loved and strive in a world that is sometimes set against you.

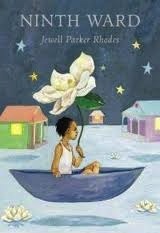

Years later, I was just about to publish a book of Louisiana mysteries, so I was at a book party the day Hurricane Katrina hit, and I felt called to the world of New Orleans. Four weeks after Katrina I was on a book tour in New Orleans, and of course no one was there, there was no where to eat, and the devastation was right there, smack in my face. I’ve travelled there many times since and feel that I lived in Louisiana in another time. Race in America is still such a polarizing event, and I realized that the lowlands were always given to the poor, so naturally the Ninth Ward would flood. For my own research, and through the love of my grandmother, I came to believe in the affirmation of hope, and I wanted to show a Ninth Ward that defied the tragedy of racism and Hurricane Katrina and to show what was lost and what was gained, which is something we can all connect with on a human level.

Ruta: There was virtually no information in books written in English regarding the Soviet deportation of Lithuanians during World War II. When I started digging I was contacted by some people in Russia who said, this never happened, people were never deported to Siberia. There is a lot of information written in Lithuanian in the Museum of Genocide but the material is handwritten and my language skills aren’t good enough to decipher them. I travelled to Eastern Europe and decided I wanted to conduct interviews to get inside this period of history. I interviewed survivors in their 80s and 90s, and definitely encountered some of the challenges that Jim spoke of. The first thing they said was, “I’ll tell you what happened to me, but you have to promise never to use my name.” Fifty years had passed, but the fear and pain was still so raw, Stalin hung over these people like a shadow. [As I interviewed them] grown men would cry and one woman threw up on the table. I told her I wanted to stop the interview, but she insisted, and said, “This might be my only chance to tell my story.” I thought then, “What have I started?” and told my husband I wanted to wait and finish the book later. He told me, “It was as if you were interrogating these people, that’s how traumatic it was for them, so you have to write this book now.”

Then I learned that some Latvian students were making a film about the Russian prison system, and they had created a simulation of what the experience in prison was like. I wanted to go into the prison but the students refused. Since they were making a documentary I agreed to pay for the film so they would let me into the prison. The experience was like going into a gulag prison, where they would starve the prisoners and use sleep deprivation to break them. The students would beat us, and it was like a switch flipped in my head. I turned to self-preservation; I only thought of myself. I remember seeing a young boy who was pleading with me with his eyes to help him, but I ran away from him and refused to help. It gave me a greater respect for survivors in my book, because someone helped them. I couldn’t go through that prison experience again, because you need true courage and I learned that I was a coward.

Next week, the presentation concludes with a discussion about whether students should be introduced to books that deal with such difficult subjects.

Please visit wowlit.org to browse or search our growing database of books, to read one of our two on-line journals, or to learn more about our mission.

- Themes: Ann Parker, Jewell Parker Rhodes, Jim Deem, ruta sepetys, Tucson Festival of Books

- Descriptors: Interviews & Profiles, WOW Currents