By Marie LeJeune & Tracy Smiles, Western Oregon University

Assessment literacy- (Gallagher & Turley): [teachers’] deep understanding of why they assess, when they assess, and how they assess in ways that positively impact student learning. In addition, successful teacher assessors view assessment through an inquiry lens, using varying assessments to learn from and with their students in order to adjust classroom practices accordingly. Together these two qualities—a deep knowledge of assessment and an inquiry approach to assessment — create a particular stance toward assessment. (NCTE, 2013).

Assessment literacy- (Gallagher & Turley): [teachers’] deep understanding of why they assess, when they assess, and how they assess in ways that positively impact student learning. In addition, successful teacher assessors view assessment through an inquiry lens, using varying assessments to learn from and with their students in order to adjust classroom practices accordingly. Together these two qualities—a deep knowledge of assessment and an inquiry approach to assessment — create a particular stance toward assessment. (NCTE, 2013).

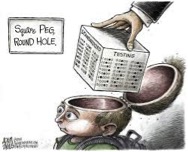

For the month of March we have presented reasons for pushing back against high stakes testing, and offered examples of how citizens comprised of teachers, parents, and community organizers are, through grassroots movements, resisting these punitive, and often harmful assessment practices.

But here’s the irony, we are firm believers in assessment—by some definitions, we might be considered obsessive.

Why wouldn’t we be? With 35 years of public school teaching between us we know well how essential ongoing, purposeful assessment is if we want to meet students’ needs and impact student learning and growth in positive ways. And we know we are not alone. The teachers with which we collaborate share this perspective. Teachers as educated experts making professional decisions understand the importance of assessment, and they are not fearful of accountability. The issue is not so much a resistance to tests that provide data such as comparative scores across similar measures and school contexts; this is important information. The resistance is driven by the time, money, and resources spent on assessments that tax public schools and benefit corporate test publishers; tests that provide excuses for policy makers’ failed policies, tests that do not provide timely and useable data for teachers to aid in students’ growth, bur rather server as fodder for ‘reformers’ to demonize schools and teachers.

For this blog we felt it was necessary to address the notion that teachers are afraid of assessment and accountability through a discussion of guiding principles around assessment that inform how we approach assessment and why we believe these alternatives are more valid than the summative and “mini-summative” assessments popular with policy makers and prevalent in schools (NCTE, 2013).

We begin with the overriding purpose of assessment, to provide as immediate as possible information about students’ needs and strengths. This may seem obvious, yet the sorts of assessments pervasive in many school districts we beleive are in opposition to this position. In the spirit of “progress monitoring,“ many schools rely on tests that fit what NCTE’s (2013) position statement entitled, “Formative Assessments that Truly Inform Instruction,” describes as “mini-summative” assessments, defined as “recently released commercial products advertised as formative assessment suggest that their main use is to prepare students for summative assessment (Heritage, 141, as cited in NCTE, 2013, p.1). DIBELS, STAR, and similar kinds of assessments are widespread in many schools and do not fit the nature of authentic, formative assessment.

|

Formative Assessments DO |

Formative Assessments DO NOT |

| Highlight the needs of each student | View all students as being, or needing to be, at the same place in their learning |

| Provide immediately useful feedback to students and teachers | Provide feedback weeks or months after the assessment |

| Occur as a planned and intentional part of the learning in a classroom | Always occur at the same time for each student |

| Focus on progress or growth | Focus solely on a number, score, or level |

| Support goal setting within the classroom curriculum | Occur outside of authentic learning experiences |

| Answer questions the teacher has about students’ learning | Have parameters that limit teacher involvement |

| Reflect the goals and intentions of the teachers and the students | Look like mini-versions of pre-determined summative assessments |

| Rely on teacher expertise and interpretation | Rely on outsiders to score and analyze results |

| Occur in the context of classroom life | Interrupt or intrude upon classroom life |

| Focus on responsibility andcare | Focus on accountability |

| Inform immediate next steps | Focus on external mandates |

| Allow teachers and students to better understand the learning process in general and the learning process for these students in particular | Exclude teachers and students from assessing through the whole learning process |

| Encourage students to assume greater responsibility for monitoring and supporting their own learning. | Exclude students from the assessment process |

| Consider multiple kinds of information, based in a variety of tools or strategies | Focus on a single piece of information |

On the other hand, authentic assessment in schools involves honoring what teachers are able to discover through formative assessment and multiples methods of engaging in “kidwatching” (Goodman, 1978). In a recent NCTE seminar on assessment, Scott Felkins commented that, “Real assessment, the kind of quality formative assessment that leads to changes in instruction and student learning, is just paying really close attention to kids.” (2014). Does this close watching of students’ reading, writing, mathematical skills, etc. involve instruments and data collection measures? Sure, it often does. But theoretically and philosophically (and practically) at its heart, authentic assessment involves careful consideration of not only what a child is working towards, but what a child can actually do. Those who argue that assessment means something removed from the actual individual child would do well to remember “The word assess comes from the Latin assidere, which means to sit beside. Literally then, to assess means to sit beside the learner” (Stefanakis, 2002).

Do we believe that summative assessments will disappear or that they should? No. Would we argue that summative assessments are best designed by those that work with children on a daily basis or at least by those that have normed assessments in classrooms alongside teachers? Absolutely. But we also deeply want to argue for the enormous importance of and the need to return to classroom data that is gathered through the use of formative assessments. These assessments offer timely information to teachers, parents, and students about a child’s performed ability throughout the school year rather than relying upon ‘snapshots’ of performance, which are often taken in faulty and false conditions (large scale summative assessment, including, but not limited to the SBAC and the PARCC.)

Assessment has come to mean something that it was never meant to be. Assessment is a method of learning about a child and alongside a child. Formative assessments need to be recognized as the valuable source of data that we know they are. On that note, we include this excellent reminder of what formative assessment is and is not from NCTE.

NCTE (2013). Formative Assessment that Truly Informs Instruction. NCTE Position Statement, retrieved from: http://www.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Positions/formative-assessment_single.pdf

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit archival stream.

- Themes: Marie LeJeune, Tracy Smiles

- Descriptors: Debates & Trends, WOW Currents