Every year we look forward to the American Library Association’s announcement of award winning books. The winning books have been exceptional and this year continues that tradition. This month we share our take on four of the ALA award winning picture books for 2016:

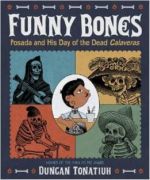

Last Stop on Market Street written by Matt De La Peña, illustrations by Christian Robinson, winner of the John Newbery Medal, the Caldecott Honor Medal and the Coretta Scott King Illustrator Book Award. Waiting written and illustrated by Kevin Henkes winner of the Theodor Seuss Geisel Honor Award and Caldecott Honor Medal. Funny Bones; Posada and his Day of the Dead Calaveras written and illustrate by Duncan Tonatiuh winner of the Pura Belpré Illustrator Award and the Sibert Award. Trombone Shorty by Bryan Collier winner of the Coretta Scott King Illustrator Book Award and the Caldecott Honor Medal.

Last Stop on Market Street, written by Matt De La Peña, illustrations by Christian Robinson.

Mary:

On the surface, De La Peña’s prose reflects the inquisitiveness of young CJ and the delight his Nana experiences when she answers CJ’s “How come…?” questions. The tone of the story shifted for me when I realized that CJ’s questions stem from displeasure and perceived injustices, not from wonder and curiosity. In a word, CJ is complaining. In a roundabout way, CJ complains about the rain, about riding the city bus and about having to go to Market Street. Subsequently, CJ’s complaints necessitate responses from Nana which I found insightful, inspiring, and hopeful. Nana’s gentle responses convey the wisdom of a woman who has seen much, experienced even more and can find beauty hidden in the world around her. Fortunately, the beauty conveyed in Nana’s responses is not lost on CJ who wonders “how his nana always found beautiful where he never thought to look.”

On a deeper level, De La Peña subtly situates the characters in spirituality and faith. The story opens with Nana and CJ leaving church on Sunday before they venture to Market Street. At first, this scene seemed to be disconnected to the story but, reading on, I connected Nana’s responses to CJ’s questions to Ecclesiastes 3:11-13 from the Christian Bible (which I can only assume Nana reads in church):

11 He has made everything beautiful in its time…12 I know that there is nothing better for people than to be happy and to do good while they live. 13 That each of them may eat and drink, and find satisfaction in all their toil—this is the gift of God.

As the story unfolds, Nana finds beauty and purpose in the rain. She finds beauty and happiness when she and CJ ride the city bus to Market Street; with the driver, with the passengers they meet and even with the bus itself. Nana and CJ both find beauty and satisfaction in the serving the people on Market Street. I wonder if De La Peña’s inspiration for this story came from Ecclesiastes. It’s a question worth asking.

I found Robinson’s acrylic painting and collage illustrations aesthetically appealing. The straight lines and crisp edges of the buildings, the cars and even Nana’s hair add a sense of purposefulness to each object in the collages. I can imagine Robinson carefully painting each object, cutting it out and placing it in precisely the right place on the page.

I especially like that Robinson portrays Nana smiling on every page. Her smile together with her words create a character that I liked immediately. I think other readers will connect with Nana as well.

Tracy:

Yes, Mary, much of what you observed about this beautiful text I completely agree with. The masterful way the story unfolds from what appears to be a nagging boy, to revealing perspectives about the urban poor in the United States. While Nana does, as you point out, guide CJ in seeing the beauty in humanity, I think De La Pena is making a strong statement about the truth of poverty, in CJ’s observations of the dirty and seeming unattractiveness of the poor side of town. My favorite line in the book is when CJ asked his grandmother why it was so ugly, to which she observes that it makes people, “a better witness for what’s beautiful.” This whole story does that for the reader I think.

In an interview I heard on NPR with Matt De La Pena about this book and the need we feel to shelter children from harsh realities such as poverty and homelessness, he said this about Last Stop on Markey Street,

You can feel like you have been slighted if you are growing up without, if you have less money, or you can see the beauty in that. And I feel like the most important thing that’s ever happened to me is growing up without money. It’s one of the things I’m most proud of.

I love this book. I envision this being a book that could invite rich discussions about social activism, poverty, and the funds of knowledge available in all communities.

Waiting by Kevin Henkes

Mary:

Henkes has written and illustrated yet another delightful book for young readers. The soft, muted cover illustration invites readers to join the story characters waiting patiently on the window ledge for the next wonderment to appear. Sometimes the wonderment appears outside the window; the wind, the lightening, the snow. Sometimes the wonderment appears inside on the ledge; a visitor from afar, a new friend.

Two aspects of Henkes’ book captured my attention. First is the setting of the story. The story takes place inside (a home?) on the ledge of a rectangular, four-pained window. Because readers share the same view as the characters, Henkes has covertly positioned them in the story waiting along with the pig, the bear, the dog, the rabbit and the owl. I felt like one of the group and I began imagining the wonderment I was waiting for. Readers will surely feel themselves dropping through the pages of the story onto the ledge to wait for their own wonderment to appear.

The second aspect that captured my attention is the placement and size of the window and the perspective it offers readers. Henkes centered the window, giving it prominence on the page. The window covers most of the page yet it doesn’t consume it. Rather, it provides a focal point for readers. The window beckons to readers, “Look here!” The perspective of being inside looking out the window with the characters gave me a sense that I had a place in the story and could participate in the waiting. If my view would have been outside looking into the window, I would have felt like an observer rather than a participant.

Henkes’ theme of Waiting will resonate with readers young and old. At times in our lives we’ve all had to wait for something or someone. The pig, the bear, the dog, the rabbit and the owl (and Henkes) remind readers that good things come to those that wait!

Tracy:

“Delightful” is apt in describing this lovely book. The soft illustrations are dear, and like you, the perspectives were an aspect of the story that drew me in. I also imagined young readers being surprised by the images outside the window, such as the movement through the seasons, the other amazing events taking place through the window. I thought how much fun the young reader would have sharing what they know about what’s going on outside the window.

However, this book didn’t grab me. While I appreciate the illustrations, and the “waiting” theme, I found myself disappointed that some of the toys were waiting for nothing, and I felt like there was just a kind of incompleteness with regards to the plot. However, your statement that, “ Readers will surely feel themselves dropping through the pages of the story onto the ledge to wait for their own wonderment to appear” is compelling; perhaps I just didn’t get that the first time I read it, and will read it again from that perspective. I did think about the interactive potential of the reader with the illustrations as I read the book.

Funny Bones—Posada and His Day of the Dead Calaveras by Duncan Tonatiuh

Mary:

Part biography, part history lesson, Tonatiuh weaves together the struggles and accomplishments of Jose Guadalupe Posada’s life with historical details of Mexico from the mid-to-late 19th century. Of particular interest to Tonatiuh is the creation and evolution of Posada’s much-loved Calaveras. Readers will delight in this long-overdue story of how the Calaveras came to life (pun intended).

At least eight of Posada’s original illustrations are featured prominently in Funny Bones. Calaveras dance, ride bicycles and propose marriage. A few illustrations portray Calaveras acting out Posada’s beliefs and feelings about la Revolución in 1910. Because little is known about Posada and his Calaveras, Tonatiuh provides captions in which he shares his wonderings about the intentions of Posada’s illustrations; “Was [Posada} saying that…no matter how fancy your clothes are on the outside, on the inside we are all the same? That we are all Calaveras?” (p. 23).

I appreciated how Tonatiuh provided me with a glimpse into the evolution of Posada’s art mediums. Posada began his printing career as a lithographer. He also learned to engrave and to etch. Tonatiuh explains the complexities of each art form with simple step-by-step descriptions and images. As a non-artist, I appreciated Tonatiuh’s explanations.

I thought about the intentions of Posada’s Calaveras as I’m sure others have as well. I surmised that Posada is reminding us of the common fate that all humans, regardless of race, religion, political affiliation, sexual orientation, occupation and so forth will end up as Calaveras. Posada might be suggesting that despite our outward differences, we are more alike than different (literally) on the inside. Posada might also be trying to say that joy and happiness can be found in the afterlife. It might also be possible that Posada’s art, similar to the claims of other famous artists like Rene Magritte, means nothing beyond what we see on the page! Regardless of Posada’s intentions, I suspect the story of his life will be wildly popular.

Tracy:

Mary, seeing the Calaveras come to life (to steal your pun) was not only unique, but a story that inspired a visually extraordinary book full of information, both biographical as well as history and politics. I loved Tonatiuh’s Orbis Pictus honor book, Separate is Never Equal, and I think this book may be even better—

A standout feature (of which there are many) was the way the political statements were portrayed through the Calaveras. I can’t think of many examples of political cartoons and posters that would reach a young audience, but in this book they are accessible because they are presented within the larger biographical narrative that focused more on the man than the details of this period in history. The illustrations of the man, his cartoons, and the artifacts are positioned to make this book nothing short of compelling and stunning. I think there is no end to what a teacher could do with a book like this in the classroom with all its connections to history, art, activism, and political satire (as well as including detailed back matter).

Admittedly, I have always loved the creepy lure of the Calaveras, but never knew, or thought to ask about their history, or the traditions they represent (and my grandfather was Mexican!). Reading this book expanded my appreciation for this art form, and deepened my interest in Mexico’s history and people.