by Holly Johnson & Susan Corapi

I Am a Bear by Jean-François Dumont

Holly:

USBBY’s Outstanding International Books (OIB) list for 2016 came out in January, and there are so many wonderful books on that list to discuss, Susan! I thought we might want to take this month’s My Take, Your Take to focus on books that we both really enjoyed reading to address how those books spoke to us particularly, and perhaps how they can be viewed through the lens of “disruption.” Many of the books from the 2016 list (all the books were published in other countries first, but made their US debut in 2015) have the potential for disrupting the status quo, the way many of think about the world, and those within it, or even what often become the focus of stories for young readers. I am going to start with a personal favorite, I am a Bear by Jean François Dumont. This is a picture book that falls under the P-2 category on the OIB list, but I think readers of all ages will be disrupted by the story. It is about a bear that finds himself in a city, not sure how he arrived there or, indeed, what he is going to do now that he is there. He attempts to ask for help, but people are afraid of him, and as he becomes more and more marginalized, he begins to internalize his marginalization. Then one day he is seen by a little girl who talks to him, but then is hustled away from the bear by her father. She notes, however, that she will “see him” again, and suddenly, the bear’s marginalized and alienated existence is disrupted. He is visible to someone else, who not only sees him, but is friendly to him. He starts to spruce himself up for the next time he sees the little girl, and thus begins to internalize another narrative about himself. With the next meeting between the little girl and the bear, the little girl mentions that the bear seems sad, and he is a teddy bear, and teddy bears aren’t sad. The light bulb goes off, the bear accepts this announcement and asserts that he IS a teddy bear and that is no small thing!

This is a wonderful book to think about ideas of visibility and the importance of our social worlds in terms of identity. I also thought about the homeless populations who are and are not visible to many of us throughout the country. In addition, I loved the illustrations. From the cover onward, this book had me! What did you think about this book, Susan? Do you see how it disrupts?

Susan:

Holly, I too loved this book from the start, and it increased my admiration for the people at Eerdmans Publishing who seem to have a great nose for finding a good book that is worth translating and publishing for North American readers. I am a Bear is a real gem!

I teach literacy to pre-service teachers, and this past week we have been discussing Peter Johnston’s book Choice Words. In chapter three he talks about how the words teachers use create identity in their students and I could not help but make a connection to the picture book. When the little girl calls the bear a Teddy Bear, that name creates a whole new identity for him, which includes being clean and happy, and receiving love. This is an enormous disruption in his way of thinking about himself.

I am a big fan of Jean-François Dumont. I have family members who work in human resources and labor relations, so I have given them books like The Sheep Go On Strike or The Chickens Build a Wall, both perceptive social commentaries but also hilarious stories! So I read his books in order to listen to a great story but I also try to read between the lines at what he is commenting on. To me this book is about the bear seeing himself in a new light, but it is also about the little girl taking the time to observe the world around her. When she talks to the bear, it moves him out from being invisible and an inconvenience into the realm of being valuable.

I just finished writing an educator guide for a book on the life of photographer Dorothea Lange (Dorothea’s Eyes by Barb Rosenstock and Gerard DuBois). The author of the picture book focuses on how Dorothea could photograph historical events but also capture the emotions of the people experiencing those events. Lange is quoted as saying “This is the way it is. Look at it! Look at it!” Now back to I am a Bear — The little girl took the time to look and to look carefully. She saw the bear’s heart, not just his smelly dirty exterior.

Holly:

Yes, taking the time to SEE someone is really important. I read some of Parker Palmer’s work and some of those connected to his The Courage to Teach, and remember reading in one of those texts about how we can “listen someone into existence.” That was very powerful for me as a teacher. We need to see and hear people. Of course, then there is the bumper sticker that says, “I love my country, but I think it’s time we started seeing other people.” That falls into this discussion as well. We have our own ideas of the world, as well as value systems, but that shouldn’t preclude us from being concerned about others. By ignoring the bear, or rejecting them as the father seemed to do, we teach our young people that some folks just don’t matter. Everyone matters. We are all part of life’s equation.

In addition to the storyline, I also love the illustrations. There is something about the look of that bear, the way he is rendered that really suits my eye. I think it’s important for young readers to also attend to the illustrations more explicitly and this is a nice book to do that, along with the wonderful Like a Wolf by Géraldine Eischner (Antoine Guilloppé, illustrator) that we will talk about it a few weeks. What do you think about those illustrations?

Susan:

I am a big fan of Jean-François Dumont. His cartoon-style illustrations make me chuckle! I really enjoy that in the middle of this story about marginalized identity, the old lady’s hair shoots straight up, her zig-zag-shaped umbrella has obviously been used to hit objects, and the big lumbering bear has to put on quick bursts of athletic speed to escape pursuers. So in between the serious notes, there are sprinkles of slapstick humor that invite readers to laugh and look carefully at details. Dumont’s attention to the small things make me want savor the illustrations over and over. I also like all the touches about France, Dumont’s home country. Having grown up there, the signs, the shape of the buildings, and even the store window at Charcuterie Legoff bring back lots of memories of being in similar neighborhoods. I think the images give a taste of living in another country, an important feature in a global book.

I am learning to read visual images, so I noticed the various perspectives Dumont uses, everything from views lower than the main character, to face on, and even a bird’s eye view as the bear and the little girl hustle down the street to meet each other. I am still wondering how these different perspectives contribute to the theme of disruption. I also noticed the way he uses grayscale and shadow in several images, particularly when talking about the invisibility of the bear and the way the little girl notices him. These images definitely contribute to another theme you introduced, that of visibility.

Our next book is also about bears. We move from one imaginary story about a marginalized bear, to a novel about bears being marginalized in a different way. I am anxious to hear what you thought of Moon Bear.

Moon Bear by Gill Lewis and Alessandro Gotardo

Holly:

Another book that fits nicely under the topic of disruption is Moon Bear, a wonderful chapter book about a young boy from Laos who grows up in an area inhabited by moon bears. This book shows readers what happens when they take action to disrupt common, but damaging practices involving animals. Tam is 12-years-old, and must go to work to keep his family from starving after an entrepreneur promises his village that if it moves from prime land for forestry, they will have everything they need at a new location he has set up for them. Tam goes to work on a farm that harvests bear bile as a medicinal product. But one of the newest bears is the young moon bear he saw just before he left his village. Tam cannot stand by and let the young bear be milked for its bile as such practices eventually kill the bears. What Tam does to save the bear places his life and perhaps even the lives of his community in danger.

I really enjoyed reading this book, Susan! Tam was a dynamic character that could serve as an excellent role model to middle school readers about what it takes to be an advocate for animals. By disrupting the common practices that others might be afraid to do, Moon Bear shows that sometimes advocacy takes more than one person to make change. So often we are given solitary heroes in books when change is seldom accomplished by one person. And while I really liked the book, I know that parts of it took coincidences and instances of serendipity to have the ending turn out. Of course, books are meant to inspire us, and well, I believe in coincidence and serendipity! What did you think of the book, Susan?

Susan:

This book was interesting on several levels. First the author — I was not at all surprised to find out that she is a veterinarian turned author. Her concern for animals and their well-being was palpable in the story. The action was more than just focused on keeping moon bears from dying; it was also focused on letting them have the chance to live out their bear existence the way they were created to do so. A second aspect that grabbed my attention was the setting of the story: the mountains of Laos, the Mekong river and the city where most of the action takes place. The descriptions of the climate were so sensory-laden that I could almost feel the city heat, smell the array of foods, and feel the mountain breeze and the damp earth. I did wonder how Gill Lewis could know so much about Laos. She did travel the world when she was practicing medicine though her site does not specifically mention spending time in Laos.

While her research process is not clear from her website, what is very clear is her advocacy for animal and environmental concerns. Her pen becomes a mighty weapon as she disrupts what are accepted practices by describing in a story how they impact animals. Her books have won the Green Earth Book Award several times. I appreciate her good writing combined with her awareness of social issues presented from an adolescent protagonist’s point of view.

Holly: What I further noted about the book was Tam’s advocacy. He was forced to work because of family circumstances, but in the working with the moon bears, he discovered his own will and what he was willing to do to save at least one bear. Then, of course, his work with his friend when the bear performed on the streets could be considered another way he advocated for himself, while not necessarily the bear. Of course, when his friend betrays him, Tam realizes that he must also start to listen to his own inner voice, which is a great model of ethical advocacy. There are many examples of advocacy in this book, Susan. That alone would make this a nice book to use with students and then to discuss advocacy and ethics. What did you notice about how people became advocates?

Susan: Tam does a lot of growing and changing over the course of the novel. He starts out as a boy who is manipulated by his best friend into trying to capture a moon bear. Through the death of his father, he ends up taking on the role of breadwinner, and works for a “doctor” who collects bear bile for medicinal purposes. His job is to care for the bears, and he does so diligently, in the process maturing into a person who stands up against the maltreatment of the bears. What is interesting is the way Tam’s concern rubs off on the family he boards with (the Sones) and the General’s daughter. You asked about the way people become advocates. In the end, the Sone family and especially the General’s daughter join efforts to make a way for Tam to rescue the bears. In the beginning of the story each character was more concerned about their own survival, but watching Tam care for and sacrifice for the bears gives them the inner drive to help him save the bears at the risk of their own well-being. So in answer to your question, I think this story demonstrates that people become advocates when they admire someone who models it for them.

The Last Leaves Falling by Sarah Benwell

Holly:

Our next book, Susan, disrupts ideas of life and death, and well, who gets to decide. The Last Leaves Falling takes place in Japan, and is about Abe Sora, who is 16-years-old, and has ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease), which is quite rare in teenagers. Abe has a lot of interests, but finds as his body no longer allows him to even go to school, he begins to wonder about the quality of life rather than the quantity. He eventually finds friends through an online chat room, and their adventures bring new dimensions to Abe’s life. But Abe’s body is still deteriorating, and he begins to think about the practices and poetry of the ancient Samurai, and through his exploration of those two interests, Abe makes a decision about his life. This book not only disrupts readers’ thinking about life and death, but also stereotypical ways of being in the world by sharing ideas based on the philosophy of the Samurai. The book was quietly beautiful. I absolutely loved it. What did you think about this book?

Susan:

I too really enjoyed the book. I found it refreshing—not because of where Abe Sora ends up in his decision-making, but because it was not the typical “death” novel that seems to be abundant these days. It disrupted my own views of that book genre by giving me a different perspective on a teen facing the death of his dreams for an education, for the chance to marry and have a family, and for a happy life for his mother.

I am still “ruminating” on this book! I think where I still struggle is with Abe Sora’s friends. I have a hard time imagining helping my best friend end his life, so the ending seems a bit unbelievable. The rest of the novel is a rich development of the teen characters and the mother. The author makes Abe come alive with all the joys of a teen life and his disrupted dreams because of the disease.

Holly:

You know, we talked a bit about advocacy in our conversation about Moon Bear, and I find myself thinking about that topic in respect to this book as well. Abe Sora becomes an advocate for himself, and how he wants to live the rest of his life. I would also say he advocated for a quality of life that is so important for young adults to address in respect to their own lives. We should all be asking questions about how we are living our lives and is this our best and most ethical life? Now I’ve gone and added ethics to this discussion, just like Moon Bear. It is interesting how these books have similar themes in them. They both deal with tough subjects, issues of ethics and advocacy, and are also told in a thoughtful and almost quiet manner, even though there is a lot of action in both of them. What do you think?

Susan:

I think you gave me a window into thinking about the book. Both books are about advocacy in different forms, one advocating for bears and the other for dreams and quality of life. The teens each become advocates for their dreams. However I feel bad for the mother — her dream of a life with her son is cut off prematurely.

Like a Wolf by Géraldine Elschner and Antoine Guilloppé

Susan:

I am reminded of our discussion of disrupted identities in I Am a Bear when I think about our next book, Like a Wolf by Géraldine Elschner and Antoine Guilloppé. Here is an animal who looks like a wolf and so is treated like a dangerous beast bent on destroying life. He is locked in a cage and ignored because of the way he looks. Then his life changes dramatically because someone looks at him with a different lens. The contrast is striking! He goes from being a predator to a herding dog for sheep, some of the most vulnerable animals around. The words are simple and few and the illustrations are silhouettes with just touches of other colors. Yet they work together to describe how the dog’s identity as a wolf keeps being reinforced. The images create fear and a sense of danger while the words counter that impression, giving voice to the dog’s feelings.

I am curious about your thoughts about this book!

Holly:

I love Like a Wolf! It, too, fits into the same category as I Am a Bear for me. The illustrations are stunning, and the storyline of rejection is disrupted when someone sees the dog for what he actually is, not what some perceive him as. You know, I am really pondering the idea of reality and perception right now, and this book and Bear are really making me think about the differences between reality and my perceptions of the world. I can only speak to my perceptions and recognize that only I can change my perceptions (often with the help of others or books, etc). So many times perception is reality until we step aside from our own egocentricity or ethnocentricity to begin to see and learn from others that life and the world and others are so much bigger, and better, than to what extent my perception limited them. Of course, it’s hard to step aside from or outside of our realities, and there is something to say about perception is reality. But Like a Wolf can help us rethink some of that. Did you like the illustrations?

Susan:

I loved the illustrations! They are extraordinary on so many levels. The black/white contrast reinforces the story and the dichotomy you mentioned between reality and perception. They accentuate the idea of danger and make the reader believe in the danger of this wolf-like canine. They also communicate the dark world the dog lives in, locked in a cage with no chance to run out in the fields. In contrast, the words make the reader understand the reality of the dog’s feelings, and that he is not really dangerous at all.

It was visually interesting when the illustrator added a touch of burnished red color when the shepherd arrived. The red of the sky in the early illustrations is almost a foreshadowing of the disruption in the dog’s life when the shepherd arrives and is viewed for what he really is, a sheepherding dog, not a wolf. Then the images change dramatically with lots of green and sunlight instead of shadow and silhouettes. I also noted the end pages. The first is a cityscape and the last is an incredible view of the dog’s life out in the open under the vast expanse of the sky. Gorgeous! What a disruption from one end of the book to the other.

When you wrote about reality vs. perception, you mentioned that we need to step out of our own ethnocentricity or egocentricity to see and learn from others. How do you think that “stepping out” happens in this book for the dog and the shepherd?

Holly:

I would be overstepping my knowledge base if I understood the perceptions of animals! Ha! But, to address your question, I think the dog had to “remember” the kindness of humans, and there is evidence for animal memory. Just watching the YouTube videos and how animals react to the humans who raised or rescued them shows that animals have memory. In such cases, I guess animals are “stepping out” of the reintroduced wild selves to “visit” or in the case of this book, live with another human. I am not sure the human in the story is a shepherd, but that is an interesting way to look at it given how the man is represented in the book. Shepherds work with animals for a living, and thus, the man in this book was stepping out of the typical way shepherds exist with their flocks and the dogs that help them with the flock. They raise and train animals to do such work. This man saw beyond the cage that constrained the dog and saw beyond the caged mind of the dog, freeing the dog both physically and mentally.

Susan:

I was intrigued with your idea of a caged mind, and thought back to Moon Bear. Some of the bears in Tam’s care were born in captivity, yet there was an instinctive desire for something else, for bear freedom. One of the issues in animal husbandry is making sure that the animals have a chance to live their lives the way they might have before large farm operations were developed. So chickens are free range and have the chance to hunt and peck. Cattle can roam and eat grass as it grows. Pigs can wallow in fresh mud from the last rain. I think that just as each animal in these books has wanted to run free, we have a responsibility to give that quality of life to animals in our care.

Our next book talks about that same care, but in this case it starts with trees.

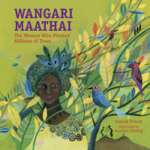

Wangari Maathai by Franck Prévot and Aurélia Fronty

Susan:

It is no wonder that Wangari Maathai has been the subject of multiple picture books. She is a person who disrupted the status quo one tree and one woman at a time. This latest picture book by author Franck Prévot and illustrator Aurélia Fronty, both from France, describes the small steps that Maathai took “with her voice and her hands” that led to the Green Belt Movement in Kenya. The movement has now spread to other places in the world and has helped curb some of the careless deforestation that has impacted the earth’s climate. But, according to this narrative, it started with a question that disrupted tradition. Wangari’s brother asked why his sister did not go to school and their mother had the courage to go against conventions and send her daughter down a path that provided Wangari with the education that allowed her to impact her world.

Each one of the other picture books has told Maathai’s life story with a particular focus. For example Claire Nivola’s Planting the Trees of Kenya focuses on the “oneness” that Maathai felt with nature. In Kadir Nelson’s version, Mama Miti, he points out the way Maathai provided a way for women to earn money to support their families. This book by Prévot and Fronty anchors Wangari in the history and social struggles of her country. It describes how Wangari not only worked to disrupt the destruction of the forests but also how she disrupted the status quo by speaking out instead of bowing her eyes and just listening as women were expected to do.

I was fascinated by the illustrations and want to know your take on how they build on that theme of disruption.

Holly:

I also saw where this book on Wangari Maathai illustrated her ability to disrupt the status quo through, of all things, planting trees of peace! She just would not quit! And what I found so shocking was not that SHE wouldn’t quit, but the Kenyan government had such a difficult time with what she was doing that it was willing to go to the lengths it did to try and stop her. I mean, when you think about it, it was “one woman, one tree”, but when the movement started to grow, well, the government wasn’t going to let any movement start — especially one that would disrupt (that word again) what the government was allowing to be done to Kenya. So, this book is about a series of disruptions that start with the disruption of the earth and how the Kenyan people may have started out living with nature, but that was disrupted by how the products of the earth could benefit the privileged few and thus nature was forsaken, as were the traditional values of the people. Then Wangari starts her tree-planting, which is such a small disruption, but then it starts to grow creating another disruptive practice that in an effort to save the earth, and perhaps by extension, the people of her country.

In addition to the aspect of how one person can make a difference to a community, a country, and eventually the world, this book’s illustrations are fantastic. They expand the theme of disruption by being bold, by showing how one bold woman took it upon herself to plant “trees of peace” and the beauty those trees could produce. The color scheme alone will not let a reader sleep through the book—those illustrations speak! They remind readers of how color in the world is brought by flowering plants and trees. The colors also bring the color back to Kenya, which was being stripped of its natural beauty with deforestation.

By planting trees, Wangari was planting peace, and it seems we don’t want peace in the world. The illustrations, while bold, invite readers to see how nature can produce a kind of peace within our psyches. What did you think of the illustrations, Susan?

Susan:

I have always loved primitive art, so I buy the jigsaw puzzles representing art like that of Grandma Moses. Aurélia Fronty’s art appeals to me in the same way. Some of the paintings are simple, rendered with almost stick figures, while in others the web of lines communicate the complexity of the story. I don’t think Wangari’s life was simple, so those webs communicate how she was impacted by her love of nature, by her concern for women and nutrition, by the politics of colonial rule and the President’s policies, and by the impact of deforestation on how people could grow food and sustain life. The webs also communicate the many ways Wangari and the Green Belt Movement impacted Kenyan society: it provided a way for women to earn money for their families; it kept the soil anchored; it challenged the status quo of the President. In a sense Wangari began to restore the rhythm of nature to Kenya and rural life.

I think you nailed it when you said that the bold color keeps us all awake and noticing the actions of this bold woman! I love the colors and they make me want to read and reread so I can absorb all the details and the glorious bright hues. Right after I finished college I taught school in the Ivory Coast for 19 months. One of the things I remember the best is the color—the vividness of the clothes, the redness of the soil and the mahogany wood, the bright hues of flowers, even the rainbow-colored belly of the cobra—all were a riot of wonderful color, and Fronty’s illustrations communicate that wonderful part of the African landscape.

I am curious about your last comment when you said nature produces a kind of peace in our psyches. We have been noticing disruption in these books and that is sometimes the antithesis of peace. But Wangari disrupts in a way that restores peace. One of the opening lines in the book says that Wangari dug holes with the women in which they could plant hope for today and trees for tomorrow. I link hope with peace, and that hope is a part of all the books we have talked about. So I guess my concluding question for you is one that goes across all the books: how does each book encourage us to keep disrupting, keep working for peace, and keep hanging on to hope?

Holly:

I think all these books disrupt practices that break the possibility of peace and peaceable living (harmony) in the world. All the books give readers hope—the hope for making a difference, for living our fullest lives, for living ethically, and for advocating for ourselves and others in ways that benefit the world. I don’t see disruption as the antithesis of peace, but rather the rethinking of the status quo that is often harmful to people, the environment, and the other species with whom we share the planet.