Learning About Ourselves and Others through Global Literature

Prisca Martens and Ray Martens

In 2011-2012 our literacy community came together to investigate the intercultural understandings young children develop about themselves, others, and the world through experiences with global picturebooks and their use of art to express those understandings. Our community included eight teachers from Pot Spring Elementary School in Timonium, Maryland: Christie Furnari teaches pre-kindergarten; Elizabeth Soper and Darlene Wolinski teach kindergarten; Stacy Aghalarov teaches art; and Michelle Doyle, Jenna Loomis, Laura Fuhrman, and Margaret Clarke-Williams teach first grade. We, Prisca and Ray Martens, are professors/researchers who teach literacy and art education, respectively, at Towson University. As a team, the ten of us met monthly over the year to discuss readings and develop understandings about intercultural learning and global picturebooks, share what was happening related to global literature in each classroom, look at examples of children’s written and artistic responses to the literature, and plan for the coming weeks. Our work was supported by a Literacy Communities: Global Gateways to Innovation Grant from Worlds of Words and by a Learning & Leadership Grant from the National Education Association Foundation.

In this vignette we provide background information about the school, the children, and our work to contextualize the vignettes that follow. In those vignettes, the teachers share specific books and experiences they had with their students around global picturebooks.

Setting the Context

The growing interconnectedness of our world economically, politically, and socially makes it essential that children develop intercultural understandings to foster and support their respect for and appreciation of different cultures and ways of life and realities around the globe (Allan, 2003; Banks, 2004). Pot Spring’s diversity provides added richness for developing these understandings. With 41% of the 550 students being European American, 29% African American, 17% Asian/Pacific Islander, and 13% Hispanic, the school is a small microcosm of the world. Each of the seven classrooms included at least one child (usually more):

•who was born in another country; for example, China, Pakistan, El Salvador, Columbia, Senegal, and India;

•whose family immigrated to the United States within the past 10 years from places such as Guatemala, Kenya, Trinidad, Mexico, Zambia, Iran, and Egypt; and,

•whose family spoke a language other than/in addition to English at home, including Persian, Punjabi, Urdu, Polish, Kiswahili, Arabic, Greek, Mandarin, and Khmer.

The children lived and breathed diversity daily! Global literature provided opportunities to build on and highlight this diversity (Freeman, Lehman, & Scharer, 2007; Short, 2011). This literature depicts cultures, regions, and people outside the reader’s country and includes books published first in another country then translated and published in the United States and books published first in the United States but with settings outside the United States (Hadaway, 2007; Short, 2007). Good books, as Rochman (1993) states, break down barriers and let readers “know people as individuals in all their particularity and conflict” (p. 19). We knew that with global literature the children would “immerse themselves in story worlds [and gain] insights into how people feel, live, and think around the world. [Children would] also come to recognize their common humanity as well as to value cultural differences” (Short, 2009, p. 1). We were confident that through discussions of and experiences with global literature the children would broaden their understandings of culture, develop a pluralistic perspective, value ways of living/being in other parts of the world, and understand interdependence among people/nations (Allan, 2003; Banks, 2004; Short, 2009).

Developing Intercultural Understandings

We had two over-arching goals for our work over the school year. One was to explore the intercultural understandings the children developed about themselves, others, and the world through global picturebooks and the other was to examine how art helped the children express those understandings.

Learning About Ourselves and Others

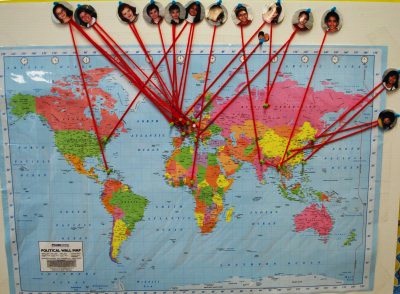

We began our exploration of children’s intercultural understandings with a focus on identity/self-awareness. As Banks (2004) states, “Self-acceptance is a prerequisite to the acceptance and valuing of others” (p. 302). To help the children begin to explore who they are and their family heritage, the teachers asked the parents to complete a survey about where/when their families immigrated to the United States. We wanted all of the children to understand that while some of their classmates moved here recently, all of their families, unless they are Native Americans, originated in another country. While conceptually this was difficult for young children to comprehend, it was a way to help them begin to develop global awareness. The teachers plotted the survey information on a world map in their classrooms, attaching a string from a picture of the child on the outside of the map to their country of origin (when children had multiple countries of origin there were multiple strings). The children took pride in putting up their string and naming their country. Throughout the year the teachers at times referred to the maps to reference where particular global picturebooks were from or the location of a certain place. The photo below is an example of one of the maps.

Figure 1. Class map showing family origins of students.

The teachers tried to read a global picturebook focused on identity every one to two weeks. The usual procedure was to read the book on a document camera so the children could follow along on the written text and read the art. The children responded to the stories, sometimes orally and sometimes first in writing or in sketches that they later shared. Through these discussions the children constructed rich meanings together, building on each other’s insights and connections. Often the teachers went back to the book to closely examine two or three of the artist’s works and talk with the children about why the artist made the particular decisions to represent story meanings.  These explorations of the art further enhanced the children’s understandings of the stories. In “Getting to Know Ourselves through Global Literature,” Laura shares how she used Sebastian’s Rollerskates (de Deu Prats, 2005) to help her children think about who they are and how they grow and develop confidence.

These explorations of the art further enhanced the children’s understandings of the stories. In “Getting to Know Ourselves through Global Literature,” Laura shares how she used Sebastian’s Rollerskates (de Deu Prats, 2005) to help her children think about who they are and how they grow and develop confidence.

As the teachers continued to read books related to identity and self-awareness in their classrooms, in our study group we talked about how to plan for the remainder of the school year. We read and discussed “Developing Intercultural Understandings through Global Children’s Literature” by Kathy Short and Lisa Thomas (2011) which outlines a curriculum framework for intercultural learning. Through this discussion the first grade teachers decided to move from a focus on identity to an in-depth study of another cultural group. Short and Thomas point out that explorations of personal cultural identities complemented with cross-cultural studies encourage students “to examine the complexity and diversity of that culture and to recognize that their personal perspective [is] only one way to view the world” (p. 152).

We decided to study India because in the fall we had read Same, Same But Different (Kostecki-Shaw, 2011). It is the story of two boys, one in America and the other in India, who become pen pals and share information about where they live. While we and the children enjoyed the story, as teachers/researchers we were concerned about the simplistic stereotypic views of both countries that came across. Since none of us knew much about India and Margaret had two students who were born there and another with ties to India, we decided it would be a good learning experience for all of us. In “Crossing Cultural Borders: Our Study of Indian Culture,” Margaret discusses how she immersed her children in learning about India. Then, in “Empowering Young Writers as Authors and Illustrators through a Study of India” Michelle shares how her children pulled their learning together to write and illustrate a nonfiction book on India. While this study was rich and meaningful to the children and to us, we know there are areas in which we can and will grow in future similar studies. For example, discussions around such topics as the interdependence among people and nations, India’s place in the world, and challenges India faces emerged and were addressed but we want to highlight those more in the future.

For their pre-kindergarten and kindergarten children, Christie, Elizabeth, and Darlene felt strongly that rather than focus on one particular cultural group, they wanted to continue to look across cultures with a focus on helping their students understand themselves and their relationships with others, including distinguishing between and celebrating how they, their families, and their lives are similar to and different from others. Since this understanding is a major concept, the teachers wanted to spend the year reading, discussing, and inviting the children to respond to global picturebooks related to this focus. In “Learning about Ourselves and Others in Pre-Kindergarten and Kindergarten” they provide examples of their work with their students around these books and some of the exciting things that happened in their classrooms.

Sharing Understandings Through Art

Art is one of a range of modes through which humans communicate meaning. Other modes include music, movement, oral and written language. While some modes may be foregrounded over others at particular times and not every mode is viable for communicating in every instance, all modes are equally valid and significant for sharing meaning (Bezemer & Kress, 2008). Schools and society, however, tend to consider written and oral language to be the modes central and primary to communication and place much less value on other modes (Kress & Jewitt, 2008).

For the past several years we have been examining ways to support children in reading meanings in art as well as expressing their understandings and ideas through art (Croce et al. 2009; Maderazo et al., 2010; P. Martens et al., in press; R. Martens et al., 2010). In our work we have learned that young children understand the multimodal nature of picturebooks and how meanings are embedded in both the written language and the art. They move easily and seamlessly between both to construct meaning of the whole as they read. We have seen how reading multimodally challenges children to think critically, attend to details, and make strong inferences. Our respect for picturebooks and the rich and powerful meanings they simultaneously offer through multiple modes motivate us to help children appreciate meanings expressed through art.

The art teacher, Stacy, and the classroom teachers collaborated to plan art concepts to share with the children through picturebooks. Sometimes Stacy introduced a picturebook and art concepts and had the children explore and create art using that concept. Other times the teachers introduced the picturebook and then Stacy explored the art with the children. Often, back in the classroom, the teachers had the children write a story to go with their art.

We have found that introducing art concepts to young children with global picturebooks is sometimes difficult. While the art is beautiful and the stories are rich, sometimes for young children both are complex, making it hard for the children to focus on a particular art concept. Introducing concepts in other ways, then looking at how artists in global picturebooks use them, has been more successful. In “Learning to Read and Compose Meaning in Art Using Picturebooks” Stacy shares how she used work by Molly Bang (2000) and other artists with the first graders to introduce art concepts and express emotions in art. Jenna, in “The Art in Writing: Analysis of Two Different Types of Writing Samples,” examines the differences in her children’s personal narratives when their writing is based on art they created or completed as an assessment.

We had a rich and exciting year working together and with the children, reading, discussing, and responding to global picturebooks. We hope the vignettes convey that excitement.

References

Allan, M. (2003). Frontier crossings: Cultural dissonance, intercultural learning and the multicultural personality. Journal of Research in International Education, 2(1), 83-110.

Bang, M. (2000). Picture this: How pictures work. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books.

Banks, J. (2004). Teaching for social justice, diversity, and citizenship in a global world. The Educational Forum, 68, 296-305.

Bezemer, J., & Kress, G. (2008). Writing in multimodal texts: A social semiotic account of designs for learning. Written Communication, 25(2), 166-195.

Croce, K., Martens, P., Martens, R., & Maderazo, C. (2009). Students developing as meaning makers of the pictorial and written texts in picturebooks. In K.M. Leander, D.W. Rowe, D. Dickinson, M. Hundley, R. Jimenez, & V. Risko (Eds.), 58th National Reading Conference Yearbook (pp. 156-169). Oak Creek, WI: National Reading Conference.

de Deu Prats, J. (2005). Sebastian’s roller skates. Art by F. Rovira. La Jolla, CA: Kane/Miller.

Freeman, E., Lehman, B., & Scharer, P. (2007). The challenges and opportunities of international literature. In N. Hadaway & M. McKenna (Eds.), Breaking boundaries with global literature: Celebrating diversity in K-12 Classrooms (pp. 33-51). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Hadaway, N. (2007). Building bridges to understanding. In N. Hadaway & M. McKenna (Eds.), Breaking boundaries with global literature: Celebrating diversity in K-12 Classrooms (pp. 1-6). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Kress, G., & Jewitt, C. (2008). Introduction. In C. Jewitt & G. Kress (Eds.), Multimodal literacy (pp. 1-18). New York: Peter Lang.

Maderazo, C., Martens, P., Croce, K., Martens, R., Doyle, M., Aghalarov, S., & Noble, R. (2010). Beyond picture walks: Revaluing picturebooks as written and pictorial texts. Language Arts, 87(6), 437-446.

Martens, P., Martens, R., Doyle, M., Loomis, J., & Aghalarov, S. (in press). Learning from picturebooks: Reading and writing multimodally in first grade. The Reading Teacher.

Martens, R., Martens, P., Croce, K., & Maderazo, C. (2010). Reading picturebooks: Integrating the written and pictorial texts to construct meaning. In P. Albers & J. Sanders (Eds.), Literacy and the arts, multimodality, and 21st century literacies: Perspectives in research and practice from the Commission on Arts and Literacies (pp. 187 – 210). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Rochman, H. (1993). Against borders: Promoting books for a multicultural world. Chicago, IL: American Library Association.

Short, K.G. (2007). Children between worlds: Creating intercultural connections through literature. Arizona Reading Journal, XXXIII(2), 12-17.

Short, K. (2009). Critically reading the word and the world: Building intercultural understanding through literature. Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature. 47 (2), 1-10.

Short, K. (2011). Reading literature in elementary classrooms. In S. Wolf, K. Coats, P. Enciso, & C. Jenkins (Eds.), Handbook of research on children’s and young adult literature (pp. 48-62). New York: Routledge.

Short, K., & Thomas, L. (2011). Developing intercultural understandings through global children’s literature. In R. Meyer & K. Whitmore (Eds.), Reclaiming reading: Teachers, students, and researchers regaining spaces for thinking and action (149-162). New York: Routledge.

Prisca Martens is a literacy professor at Towson University.

Ray Martens is an art education professor at Towson University.

WOW Stories, Volume IV, Issue 5 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at <a href="https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/iv5" target="_blank".