Young Children’s Explorations of Multiple Perspectives

by Jaquetta Alexander, Second Grade Teacher, Van Horne Elementary School

Young children are often viewed as egocentric, unable to consider perspectives outside of their own. My own experiences have convinced me that young children can consider multiple perspectives when they are engaged in contexts and inquiries that build from their life experiences. Therefore, when we began a semester-long inquiry into human rights I wanted to further explore the contexts that support young children in this type of thinking. I worked closely with Jennifer Griffith, a colleague who teaches first grade, to incorporate our focus on human rights into our classrooms. To give students many opportunities for exploring human rights, Jennifer and I used text sets that included picture books offering multiple perspectives on these issues. We also utilized literature discussions after each read aloud so that the students were exposed to the multiple perspectives of their peers. Finally, we developed a chart to document student thinking so that they could more easily identify their different perspectives across the books.

Several key interactions helped foster a better understanding of the broad concept of human rights and provided evidence that students were considering multiple perspectives. One in particular was our environmental study. We used a text set which included four key books that were significant for students–Just a Dream by Chris Van Allsburg (1990), The Tree by Dana Lyons (2002), Aani and the Tree Huggers by Jeannine Atkins (1995), and Someday a Tree by Eve Bunting (1993).

Prior to beginning the environmental study, we had regularly invited students to engage in thinking through read-alouds, literature discussions, and various response strategies, so they were familiar with these ways of thinking. We began our study of human rights by investigating fair and unfair experiences. When the students identified experiences in their own lives that were unfair we were able to link that understanding to human rights by explaining that those times represented their rights. For example, when Timmy shared that he had been bullied, we helped the students identify that it was Timmy’s right to not be bullied. Finally, we pushed students to think about taking action–making choices for the common good. We carefully selected books that would be both meaningful and engaging for young children to support connections to their own life experiences.

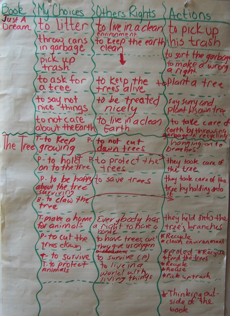

When Jennifer and I began collaborating on the environmental study we knew it would be important to keep a record of the students’ understandings. Our goal was to create connections that would support young children in constructing their own understandings of complex concepts. By creating these charts we hoped the students would recognize that people’s choices, others’ rights, and taking action were all interconnected. What we discovered is not only did they make those connections; they also showed evidence of understanding perspective. We believe that young children can understand difficult concepts as long as they are able to connect those concepts to their own lives.

The charts are a clear representation of student thinking and ability to see connectedness across texts. After reading each book the students listed both positive and negative choices made by characters. When we read Just a Dream, students stated that a choice of one of the characters was to litter, that choice affected others’ right to live in a clean environment, and the action piece was that the character eventually decided to pick up trash.

When Jennifer and I examined the charts, we realized the strong support that recording their thinking provided for students’ understanding of perspective, especially when analyzing students’ thinking about The Tree. Under the category of “My Choices,” children noted the different choices made by each character. The codes next to the choice on the chart represent specific characters (t is for tree, p is for person, and b is for bear), indicating the students’ awareness that these characters had different views. The chart doesn’t reflect the complexity of their discussion about differing perspectives. When one child said that the tree had the right to keep growing, the room buzzed with discussion. Students immediately turned to their neighbor to confer about the validity of the statement. Bailey disagreed with this perspective because, “The tree isn’t alive, it doesn’t have legs or arms.” Manny argued that the tree has choices because it has roots and they move to find water. Destini stated that the tree had the choice to do nothing because it grew underground. When the students were asked to think about how those choices affect others, Bailey responded by saying that it affects our rights because if the tree grows too big we can’t climb it. Matthew then mentioned that others have the right to not cut down the tree, and that trees have the right to grow because they give us oxygen. “And wood products,” added Tanner.

After completing the text set, students were asked about the big ideas across all four books. Their responses included:

A few days later, as a culmination of our focus on the environment, Jennifer and I put the students into groups of nine. We rotated the four key environmental books between groups and asked students to discuss the big ideas from each book and the choices made by the characters in each book to make the world a better place. Originally we planned on each group spending 20 minutes in this discussion, but we had to extend it over two days with each group utilizing about 45 minutes of time because their discussions were so on engaged and in depth in their analysis. Their comments included:

We asked the children to show what they understood about choices and human rights using various mediums, from markers to charcoal, to create a visual response gallery. Their sketches indicated that students understood that choices affect our planet, good choices result in a better world, and sometimes we make difficult decisions that require us to question.

Jennifer and I were excited about the students’ visual and verbal responses, because they provided clear evidence that young children can consider and understand differing perspectives. The ability to consider multiple perspectives was especially significant for us because our school focus has been on developing children’s intercultural and multicultural thinking about their lives and world. If we accept that young children are egocentric and so can not recognize that others have differing perspectives, then we also accept that they can not develop intercultural understandings of the diverse ways that people think and live in the world. Our students understood that they have a perspective, that perspectives change over time, and that multiple perspectives exist on an issue or event, an indication that they are building the conceptual understandings necessary for an intercultural orientation to life (Crawford, Ferguson, Kauffman, Laird, Schroeder, & Short, 1998).

We recognize that young children have fewer experiences in the world and so this type of thinking may be more difficult, but we believe that it is our responsibility as teachers to create learning contexts that support them in using their experiences to build conceptual understandings about perspective and culture. The environmental study provided opportunities for students to build on their knowledge and concern about nature in order to synthesize new information and consider multiple perspectives. These experiences gave them the time they needed to bring together their thinking to form new understandings and to develop their ability to see the world and global issues from multiple perspectives.

References

WOW Stories, Volume I, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi2/.

One thought on “WOW Stories: Connections from the Classroom”