Writing as a Tool for Synthesizing Our Learning

By Kathryn Bolasky, Third Grade Teacher, Van Horne Elementary School

We had engaged in a semester-long inquiry into journeys as a school and were struggling with how to effectively record student learning. Our students had done a great deal of webbing and mapping throughout the process that we studied as teachers to understand the development of their thinking and to make teaching decisions. We needed a summative assessment and finally decided to have the students write essays about their understandings of journeys. We hoped that writing essays would give the students a chance to synthesize their understandings by pulling all the pieces of our study together. Keene and Zimmermann (1997) explain synthesis as creating a road map of our meaning and a way of saying, “I have been there and this is what I remember” (p. 170). They argue that we use synthesis to understand something better for ourselves. Synthesis is a process of “ordering, recalling, retelling, and recreating into a coherent whole, the information that our minds are bombarded with every day” (p. 169).

I have to be honest and say that I was skeptical about whether my class would be able to write effective essays. I was particularly concerned that my students would summarize and retell information, rather than synthesize their understandings. Keene and Zimmerman (1997) state that “a summary is a listing of the parts and synthesis is somehow the creation of a whole” (p. 173). They note that a learner creates a personal composite of their understandings with a strong sense of their own voice and life experiences instead of engaging in a lifeless retelling of main points. The essays my students wrote made me realize that I had underestimated their ability to take their thinking to the level of synthesis and so I decided to reflect on the process of creating these essays. I needed to understand how this process supported them in this writing and thinking.

Our inquiry into journeys took place in our Learning Lab, a place of learning and inquiry for us as teachers. We each take our students to the lab once a week for an instructional engagement and then meet together in a teacher study group every other week to analyze student work and think about where we will go next in this inquiry. The Learning Lab is facilitated by Lisa Thomas, our instructional coach, and the focus of the work in the lab is determined by our professional learning focus as a school.

We spent the fall semester thinking about how to integrate international literature and global perspectives into our units of study. We chose Journeys as a broad concept to explore in the lab because it connected to our individual units at the different grade levels. Students had created their own Life Journey Maps and explored journey as a metaphor through various read-alouds, texts sets, and mapping responses to develop their conceptual understandings of journeys. For several weeks, we engaged in a simulation where students were told that war and fighting were right outside their homes and they had to be ready to leave quickly on a forced journey to a safer country. We read and responded to picture books about children in refugee camps and students researched the country to which they would be moving. They each packed a suitcase, making hard decisions about what to leave behind. Throughout this inquiry, we struggled as teachers with how to encourage the development of conceptual understandings and so were eager to see the thinking in their essays.

Preparing to Write

Lisa signaled the end of our journey inquiry by rereading the same story that had started our study, The Pink Refrigerator (Egan, 2007). The students were excited about hearing the story again and reacted as if they were reuniting with an old friend. As Lisa finished reading, she explained that they were going to write about their learning. She used The Pink Refrigerator to help the students understand that their writing was not an assignment but a response strategy to help them reflect on what they had learned, saying that “our writing is like the ‘Keep Exploring’ note that was on Dodsworth’s refrigerator.” This reference allowed the students to understand that there was not a right answer. Lisa explained that the goal was to use writing to push our thinking about our learning during the journey study. We started the writing process by charting our understandings of journeys on a semantic web.

The students were readily able to contribute their understandings to the web. I was happy to see that they could recall the deeper meanings of some of the books and learning engagements in the lab. They were even able to contribute ideas from journey explorations within our classroom. Lisa continued to scaffold their thinking by listing the “Big Ideas” about journeys from their discussion. The class created the following list:

Even though I was impressed that the students could discuss these concepts, I still questioned whether they would be able to pull together their thinking and ideas to effectively write an essay. It was not until the students chose the big idea that they wanted to write about, that I began to see their higher order thinking developing.

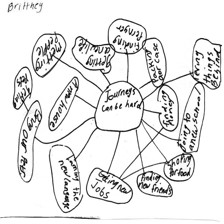

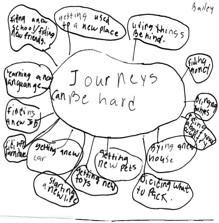

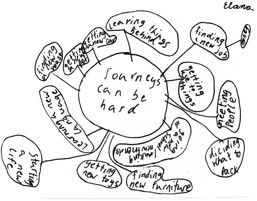

Each student chose a “Big Idea” and worked on brainstorming their understandings about that topic or issue. I sat with one group comprised of Elana, Bailey, Brittney, and Gaby. As I observed them writing I noticed that each girl was making multiple entries on their webs. I was surprised by how many ideas they each had for their topics. My students had previously used webbing as a prewriting activity, but I had never seen them produce such complete webs. Typically, their webs had three to five ideas that connected to the main idea, but in this case they each had more than ten connections on their webs.

Gaby wanted to write about how “Journeys can be hard.” Each piece of evidence for her claim was linked to the forced journey segment of our study. Instead of retelling the details about the lack of choice in leaving your home as a refugee, Gaby brainstormed examples of how being a refugee would affect her life. She backed up her claim with ideas like:

Each idea is an interpretation of concepts that were explored during the simulation on forced journeys. Gaby had gone beyond basic comprehension of the study by using herself as a lens to explain her understandings of the issues. When Gaby personalized her understandings, she was able to combine the details of the activities from the lab and our classroom with her learning to create new meanings. This was a huge step in shifting her thinking.

Upon reading the webs, I could easily identify which stories and engagements were most significant to students at this point in our study. Many made references to Gleam and Glow (Bunting, 2005), Ziba Came on a Boat (Lofthouse, 2007), Home of the Brave (Applegate, 2007), and Esperanza Rising (Ryan, 2002). Along with the stories that were read aloud, numerous students shared ideas and concepts that they gleaned during their exploration of the text sets from the forced journey study. These text sets were collections of picture books that provided information about the countries where the students were seeking refuge. Each set contained fiction and non-fiction that were authentic looks into life in that country. We even had books that were in the native language of each country so the students would be able to gain insights into the new language they would be immersed in. The complexity of their webs would not have been possible without the literature-rich environment that surrounded students during the study.

Creating Thesis Statements

Once the students compiled their thoughts about their big idea, Lisa worked with them on how to draft a thesis statement. She explained that a thesis statement is a sentence that answers the question, “What is it that I really want to say?” and provided students with a few examples of thesis statements she had drafted for her own essay on journeys. The students were handed their webs and given time to compose at least two thesis statements. Again, I was concerned about my class because I knew this thinking was new to them, but was eager to see their attempts.

I saw some students looking at their papers, with a blank look on their faces. When Lisa and I conferenced with those students, it was clear that they had a deep understanding of their learning, but lacked the confidence to write anything down. They were cautious about writing thesis statements because they had never done this type of writing before.

I found this conferencing time to be a turning point for their ability to synthesize the study in words. As I sat with Michelle, I asked her to show me her web and explain the important parts. Michelle’s central theme was the big idea that “Journeys can lead you to a better place” and she had numerous branches that provided evidence for her claim. As she read each one, I saw a pattern in how she worded each idea by repeatedly using the word “risk.” I commented that I noticed her use of risk and asked her to explain why. Her response was “you have to take risks to go on a journey.” I wrote her explanation on her paper and congratulated her on creating her very first thesis statement. I wish I had a picture of her face when she realized she had the ability to write a thesis statement. I told her that I wanted her to try to write one on her own and left her to work while I conferenced with another student. Michelle was able to create another statement as evidence of her understanding.

I was amazed at the thesis statements that my class created. They truly were able to generate statements that provided an insight to what they had taken away from our study. Each thesis was a meaningful representation of what a particular student had learned and felt strongly about. Examples of the big ideas in their thesis statements included:

The most interesting part of reading their thesis statements for me as a teacher was identifying the part of the study to which they felt the most connected. What was even more exciting was that they used strategies and evidence to back up the positions they were taking in their thesis statements.

Providing Evidence

The students thoughtfully provided examples to back up their thesis statements in various ways. Some students chose to share personal experiences to explain a concept. Darell wrote about emotional journeys based on his thesis, “When someone important to you dies, emotions can get in your way.” He supported this claim by using his experience of losing both his grandfathers, saying, “The hardest experience for me is that I keep thinking about them. It’s like my mind is crying and it’s keeping me from my work.” Andy also used personal experiences to explain his thesis, “When you move, you leave things behind.” He argued that, “Life will not fit in a suitcase. When my mom had to move she had to leave pictures of me as a kid. She was really sad because she wanted them. Refugees have to leave their homes, toys, and pets behind.” Alex made sense of changes during a journey by using personal experiences for his thesis, “Sometimes when I am on a journey, my emotions change.” He supported this claim by stating, “I was playing my video game. I was so sad. All of the sudden I got something cool and I was happy.”

All three students engaged in complex thinking to create their own meanings and explanations about what they learned. Their voices come through strongly as they work to create a coherent synthesis around their thesis statements. Harvey and Goudvis (2000) argue that “true synthesis is achieved when a new perspective or thought is born” (p. 144). This type of synthesis is what Darell, Andy, and Alex did in using their own life experiences to help them create meaning for themselves about their learning and to support a strong viewpoint in their writing.

One essay in particular stood out. Along with using personal experiences to make sense of her learning, Sarvnaz used the strategy of taking a narrative stance while writing her essay and directly addressing her audience. After completing her web, Sarvnaz created the thesis, “You need to be brave and smart when you go to a new place.” When she started writing she did not provide evidence from her life, but instead provided confidence-building pieces of advice. She explains to her reader that:

When you get to a new place it will be very difficult. All you need to is be brave and smart. You will use your brain to figure things out and when you look around you will see cars and people, just like old times.

Through this strong sense of self-confidence, I noticed several indications of Sarvnaz’s learning. First she took the stories and engagements that she experienced in our study and applied those understandings to how she would feel being forced to move to a new place. Not only does this show Sarvnaz’s ability to synthesize, but her ability to think intertextually as she made connections with past texts to create a new text (Short, Kauffman, & Kahn, 2000). Sarvnaz showed her understanding of the importance of making connections by explaining that even if you are in a new place you will have the ability to be brave by making connections in your new environment. She clearly explains that you can use what you know already to help you make sense of your new surroundings.

Writing as Tool for Synthesis

Having students write essays as a way to synthesize their learning was a valuable engagement for my students and for me. Despite my initial reservations, using writing as tool to synthesize learning helped validate the students’ understanding from this study. Looking through the completed work, I can see the small steps that supported my students in pushing their thinking and writing. They needed the richness of a learning environment where literature was a way to experience multiple ways of thinking and living in the world and a way to explore complex ideas. The instructional strategy of giving students time to brainstorm the big ideas from their inquiry and then to choose one idea to web and develop was a very important context from which they could develop a position statement and a coherent argument about that position. Having Lisa share her own thinking throughout this process provided students with a demonstration of ways they might engage in this thinking.

Introducing my students to thesis statements in third grade has undoubtedly laid a solid foundation for their academic writing schema. Understanding what a thesis statement is and how it is important to their writing is something my students see as significant and are proud of knowing. During the Love of Reading week, two undergraduate college students visited our class as guest readers. When I introduced the guests, my students excitedly asked, “Do you know what a thesis statement is? We do.” They explained that they had written thesis statements and offered the advice that you have to be sure to relate everything you write back to your thesis statement.

My students had created their own synthesis about synthesis. They had fit together the pieces of our work with essays and thesis statements to create their own understandings about synthesis as well as about journeys. They were engaged in creative, critical thinking that wove together their learning into a more complex whole. In turn, this vignette is my attempt to engage in the same process of creating a synthesis to understand this type of thinking. I only hope that I am as successful as my students in claiming this thinking for my own.

References

WOW Stories, Volume I, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi2/.

One thought on “WOW Stories: Connections from the Classroom”