Celeste Trimble, St. Martin’s University, Lacey, WA

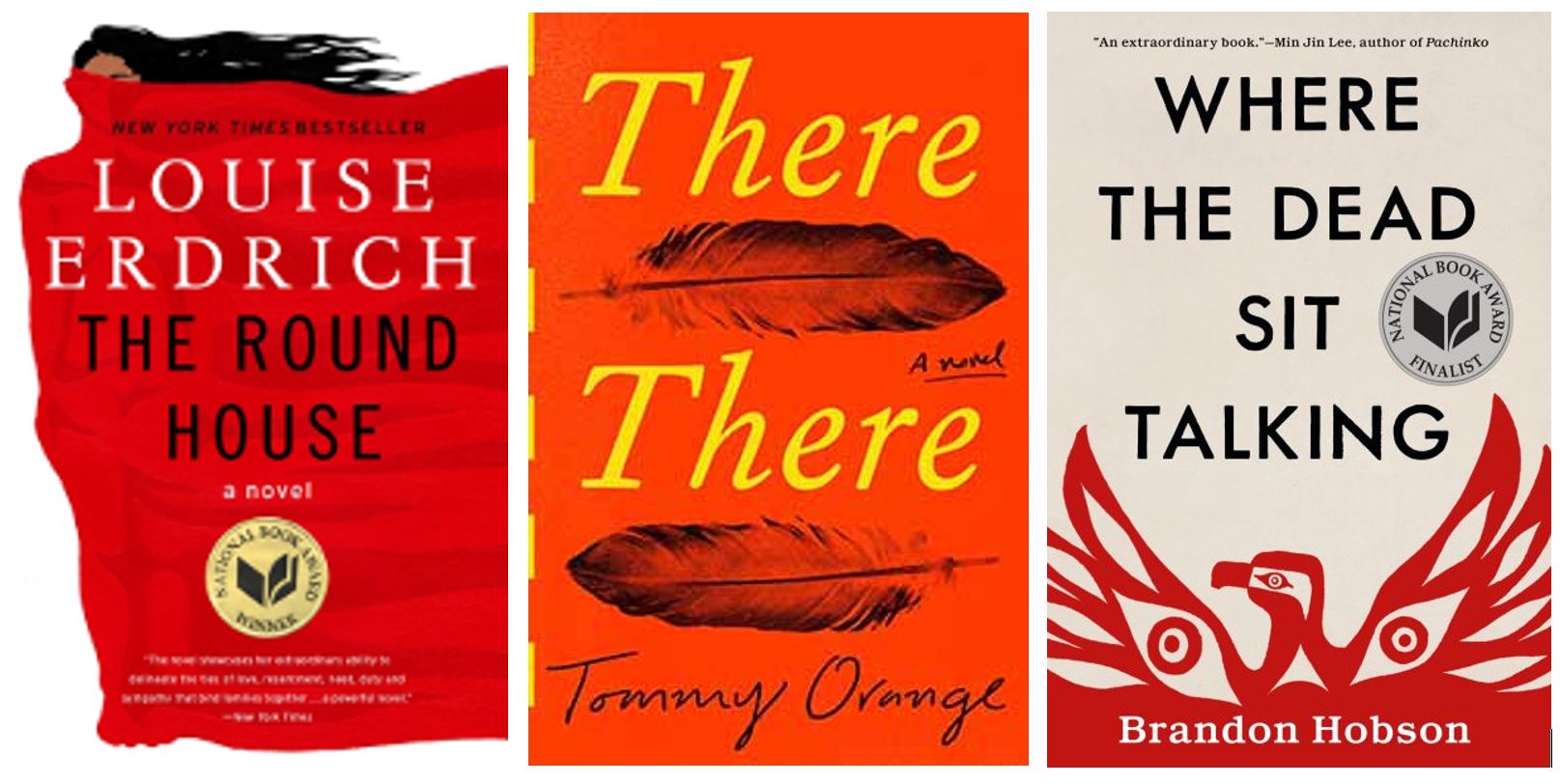

When I taught high school English at a tribal school, the primary class novel I chose was The Round House by Louise Erdrich (Turtle Mountain Ojibwe), winner of the National Book Award for fiction in 2012. Choosing a whole class novel is never an easy task. It should be appealing to everyone (impossible). It should be able to be read and understood by all reading levels in the class (unlikely). It should be important, worthy of lengthy discussion, and worth convincing students that if they just give it a chance, they may like it, and see its worth. Of course, there is also the idea that we shouldn’t read whole class novels at all, allowing students to choose all their own books themselves, thus avoiding the above difficulties. However, for me, there is something deeply pleasurable and vital in having a shared reading experience and community dialogue around this reading.

I chose The Round House because I deeply admire the work of Erdrich in general, her picturebooks, middle grade novels, and poetry and novels published in the adult market. Her language invites me to read and then read again. The complex family systems and histories that are interwoven into all of her books draws me deeply into each book. I chose this particular novel because I wanted to explore issues of justice and jurisdiction with my classes, and think about the demand for the reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act through the novel and through the lives of students.

The Round House is told through the eyes of Joe, a 13 year old boy whose mother has experienced a violent attack. Joe is deeply frustrated with the way the attack is being investigated both by law enforcement and by other adults in his life. Joe and his friends take matters into their own hands, investigating, conducting interviews, researching, and seeing through legal bureaucracies. Beyond the explorations of tribal and state laws, this novel is also a coming of age novel for Joe. He takes action when he sees that adults are not doing so, he is confident in his own judgement and abilities, he grows considerably. However, this text is told from the perspective of grown up Joe remembering when he was 13. It is this element that makes the novel officially not a young adult novel. The adult is reflecting back on his adolescence.

Similarly, Brandon Hobson’s (Cherokee) 2018 novel Where the Dead Sit Talking was a National Book Award Finalist for fiction. The novel explores the experiences of Sequoyah, a fifteen year old Cherokee boy, living in a foster care situation with Rosemary, another Indigenous teen in foster care. Their foster family is not Indigenous. It is a novel looking not only at the idea home and displacement, but also exploring questions of identity and concepts of death. The element of reflecting back on one’s life is negligible for me in this novel, and I imagine this could easily read as a YA novel for a young reader.

I met with Hobson at the 2019 Tucson Festival of Books, introducing him to a handful of the Tohono O’odham students with whom I’d read The Round House. When asked why his book wasn’t considered YA, the simple answer was because adult Sequoyah was reflecting back on his adolescent life. I didn’t get to my next question, though, which was, if we stripped that construction, that definition of YA, if we stripped the marketing considerations, could this be considered a book for adolescent readers? I imagine one of the great distinctions would be that this novel, then, would not have been a finalist for the National Book Award in fiction, but perhaps in fiction for youth, which might not have the same level of respect, unfortunately.

Another novel published in the adult market that has high appeal for teen readers is There There by Tommy Orange (Cheyenne/Arapaho). This novel won the 2019 Pen/Hemingway Award, was shortlisted for the Carnegie award for fiction, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, longlisted for the National Book Award in fiction, amongst other awards. Centered around twelve characters whose lives are interwoven, this novel addresses the lives and identities of urban Natives in Oakland, California. One character, Orvil Red Feather, is identified as fourteen years old. Tony Loneman, the first and the last to speak in the novel, is 21. Some of the other characters are not aged, but are probably in their late teens, early twenties. A few characters are older, having experienced the take over of Alcatraz in the seventies, offering the reader an important piece of urban Native history. In this novel, the youth voice is together with adult voices, so it might more easily read as an adult novel. However, I believe the youth perspective and experience in this novel is so critical that for me this is absolutely a crossover book.

I had the pleasure of hearing Tommy Orange speak this last weekend and I asked him about how marketing affects his process and his imagined readership. He said he does not think about the market at all when he is writing, does not think about audience. Additionally, he does not like the distinction between YA and adult writing.

“I don’t like the hard lines between the genres. I think there’s no reason why we shouldn’t have kid voices in adult fiction and why we can’t talk about some serious stuff in children’s literature and YA. I think all these marketing boundaries are really compromising to good work and a lot of times condescending to young people.”

While I agree that marketing boundaries can interfere with a creative work, and the process of writing, at this time it does matter how a book is categorized. This is one reason why I think the American Library Association Alex Award is a very important award category in terms of highlighting and promoting fiction written for adults that teens might find very appealing, thus busting the dividing line of YA/adult marketing a bit.

These Indigenous authored books, marketed for an adult audience, are examples of profound and important storytelling that should be experienced and enjoyed by teen readers as well.

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit archival stream.

- Themes: Brandon Hobson, Celeste Trimble, Indigenous, Louise Erdrich, Round House, There There, Tommy Orange, Where the Dead Sit Talking, YA

- Descriptors: Awards, Books & Resources, WOW Currents