Susan Corapi, Associate Professor, Trinity International University, Deerfield, IL

Photo Credit: Steve Puppe

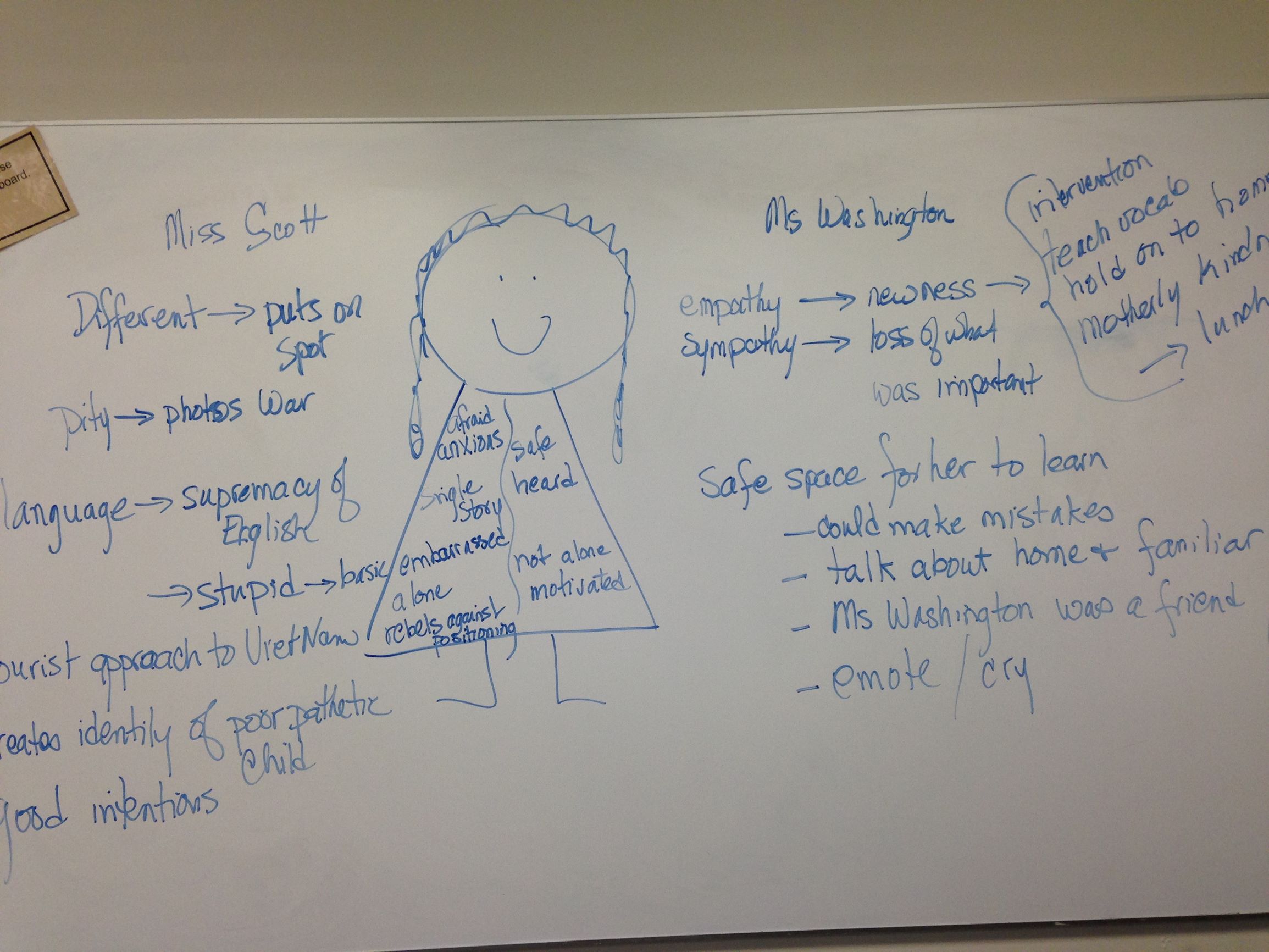

In my classes for K-12 pre-service teachers, we start by talking about the story, then we begin to look deeply at the characters. We create a three-part cultural x-ray of 10-year-old Hà, looking at the values and beliefs that motivate her actions. Then we add a section to the right and the left of our portrait of Hà, and begin to list the actions and perceptions of her teacher Miss Scott (MiSSS SScott) and her neighbor Mrs. Washington (MiSSSiss WaSShington). As we look at what motivates these women’s very different actions, students begin to understand the cultural backgrounds of Hà and the two women who are trying to help her learn and adjust. Students change as we look at Miss Scott’s misperceptions and Mrs. Washington’s compassion. In the process, refugees become people instead of a feature on the news. More importantly to me, students begin to understand the arduous journey of immersion into another country and language.

I first read Inside Out & Back Again in 2011 right after it was awarded the National Book Award. I read it in one sitting because I could not put it down. Finally, someone captured the agony of learning another language when living in a new country. Hà’s story mirrors my own. In her poems, she describes the puzzling parts of a language, the frustration of making friends with people who hold different values, and learning in a school system that is clueless about how to help the language learning and adaptation process. My journey was not forced like Hà’s–I did not move to France because of danger. But my language-learning journey was the same. That is what makes this story so powerful for anyone who is going through a culture and language shift.

Since 2011 Thanhhà Lai has written two other novels that explore other immigrant/refugee journeys. In Listen, Slowly (2015) the daughter of Vietnamese refugees goes to Vietnam to meet relatives she has only heard about. Lai captures the experience of 12-year-old American–born Mai/Mia as she accompanies her surgeon father and her grandmother (Bà) to talk to a detective who claims that Mai’s long-lost missing-in-action grandfather may be alive. During her time in Vietnam Mai/Mia begins to understand more of her cultural heritage along with learning to speak Vietnamese, a language she understood but did not voice.

Butterfly Yellow is a story of yet another aspect of the immigrant journey. Lai, along with her mother and eight siblings, escaped two days before the fall of Saigon in April 1975. They left on a navy ship and eventually arrived safely in Alabama. But many Vietnamese people were unable to escape and ended up living through years with an oppressive government intent on reeducation and punishment. On a website dedicated to recording the stories of the Vietnamese Boat People, the organizers explain that “between 1975 to 1992, almost two million Vietnamese risked their lives to flee oppression and hardship after the Vietnam War, in one of the largest mass exoduses in modern history. Escaping by boat, many found freedom in [a] foreign land, many were captured and brutally punished, and many did not survive the journey.”

I think of myself as a voice driven storyteller. I tell stories and I try to get so close inside my character’s mind that you not only know who they are and what they do. You know how they think, what they smell, how they see, what they hear. (8:04)

After Thanhhà Lai finished college she worked as a reporter in Orange County where she talked to a lot of Vietnamese refugees who came over on the “second wave” (the fishing boat wave infamous for danger and encounters with Thai pirates preying on the boats). In several interviews linked on her website Lai describes how she asked questions about their experiences but instead heard about the before and after of their trip. Their memories of time on the boat were too painful and those telling the stories were trying to forget that part of the narrative. While visiting a memorial in California, she saw a photo of a young woman who had been one of the boat people and did not survive the journey. She began to imagine what would have happened had she made it to the U.S., and the book Butterfly Yellow was born.

The subtitle of the Vietnamese Boat People website is “Stories of hope, survival and resilience.” Lai explains that Butterfly Yellow engages with the “flip” from the despair of the journey to resilience and hope that propel survivors to heal and rebuild their lives. That is the story that she hopes to tell.

Butterfly Yellow

It is the summer of 1981, 18-year-old Hằng has just arrived in Texas to look for her brother Linh who had been pulled from her arms by an American soldier in 1975 and airlifted out on an orphan plane. She has carried the guilt of letting go through the tough years of surviving in the middle of a new communist government intent on punishing any who helped the Americans and the South Vietnamese. Hằng, her grandmother Bà, and her beautiful mother collaborate on devising a plan to get them all to Texas to reunite with Linh.

It is the summer of 1981, 18-year-old Hằng has just arrived in Texas to look for her brother Linh who had been pulled from her arms by an American soldier in 1975 and airlifted out on an orphan plane. She has carried the guilt of letting go through the tough years of surviving in the middle of a new communist government intent on punishing any who helped the Americans and the South Vietnamese. Hằng, her grandmother Bà, and her beautiful mother collaborate on devising a plan to get them all to Texas to reunite with Linh.

When a malignant tumor prevents Bà from escaping, Hằng and her mother, disguised as Buddhist monks, escape in an overloaded fragile fishing boat. Discovered by pirates, Hằng survives because of her mother’s fierce defense at the expense of her own life. Eventually Hằng arrives in Texas where she has an uncle and cousins she has never met.

The uncle wants to keep her in Dallas but Hằng uses all her ingenuity to board a bus and ride across the state to the Amarillo address the American soldier pressed into her hand as he carried off her brother. Stranded but now knowing where her brother lives, her path crosses that of LeeRoy, a wannabe cowboy who dreams of riding broncos in a rodeo. However, after a series of mishaps, LeeRoy and Hằng end up working on the farm next door to her brother and his adoptive mother.

Linh (now known as David) does not remember Hằng or anything about his former life in Vietnam and refuses to even talk or interact with Hằng. Through the long hot summer, Hằng slowly works at connecting with her brother by telling him short five-sentence stories that she has laboriously crafted and practiced with LeeRoy’s help. Then the climax of the novel happens.

At the top of a Ferris wheel ride the three share, a yellow butterfly lands on David, and Hằng sings a song about a yellow butterfly that she used to sing to her little brother in Vietnam. The song clicks in his memory, and he joins Hằng in singing in a language he had forgotten and doing actions that were etched into his muscles. The tune of “Are you sleeping, Brother John” is shared beyond the siblings as LeeRoy adds in Spanish and English words and Hằng sings the song in French. The story concludes as Hằng moves in with David and his adoptive mother. The story’s ending is full of hope for the sibling’s relationships.

What makes [the story] interesting for me is how she conveys what’s inside her mind. And how you do that is you go inside and look at language. (5:12)

As an educator there are three particularly important concepts that Lai discusses in her writings and in her interviews and that I want students to notice. The first is language acquisition and how challenging it is. Language learning takes place in all three stories, whether it is Hà, Hằng or Út (in Listen, Slowly) learning English or Mai learning Vietnamese. In all three books the misconceptions about the target language are transcribed through free verse or Vietnamese phonics so the reader can begin to understand how complicated it is to train one’s ear and tongue to master a whole new set of sounds and words.

Lai explains, “So what you do when you enter a new language is you have to somehow reconfigure it to your mind so that you understand it” (WOW interview). Hà records in her journal that “All day / I practice / squeezing hisses / through my teeth. / Whoever invented / English / must have loved / snakes” (p. 118). Hằng transcribes in her mind how to pronounce English words using a Vietnamese pronunciation key. She has a cousin “En-Di,” which she notes is illogically spelled “Angie” (p. 7), and she asks LeeRoy to “Thóc sì-lâu, bò-li-sì” — talk slow please (p. 41), breaking the words into separated phonemes. Each example of speech gives readers a chance to hear what Ha and Hang hear as they try to understand and master English.

A second concept is the need to tell the stories. In an interview with Publisher’s Weekly, Lai relates her motive for writing Butterfly Yellow. When Vietnamese refugees would skip over the painful stories of their escape, Lai persisted to try and hear what happened. “I noticed that when I asked about what happened people would always say, ‘I’ve heard rumors. I’ve heard rumors that there were rapes. I’ve heard rumors that pirates would take the men.’ No one would say that it was their story, because it’s such a dark story that you don’t want to put your name to it.” (Publisher’s Weekly, 2019).

In Butterfly Yellow, Lai gradually reveals details of Hằng’s trip so the reader understands the horror of the trip. But she does so by relating flashbacks that are injected into the repartee of LeeRoy and Hằng as they muck out stables, dig post holes, or water the cantaloupes. As Hằng’s back story unfolds across the novel, Lai balances the horror of Hằng’s trip with the humorous character of LeeRoy, a teen who breaks away from the academic dreams his parents have for him to dream his own story, that of being a cowboy. Lai explains, “The story is really about healing. I didn’t want to write a story just about what happened on the boat, because I feel that’s all you get to know about [Hằng] and I wanted her to heal” (WOW interview). As an educator that shift is important. Students come to our classrooms with traumatic experiences and needing to heal. This book gives hope.

LeeRoy introduces the third concept important in these stories, that of humor and laughter. Ultimately Butterfly Yellow is about resilience, and as Hằng and LeeRoy work in the heat as farmers, they grate on each other, trick each other and slowly learn to care for each other. Thanhhà Lai is a very funny person to listen to, and she uses her sense of humor to write about the funny relationship two people can have who are from opposite parts of the globe. The humor that was part of her own family, in spite of having a missing-in-action father, infuses each of her characters, whether Hà is describing the snake hisses of English, Mai is narrating her sassy feelings as she meets “the fourth son of Ông’s second cousin” (p. 31), or Hằng is trying to understand Texas idioms.

Why are these stories so powerful? Why do they grip student after student in my classes? Why do I never tire of using them to give a window into the language learning and refugee experience? In a recorded mini-conference hosted by Worlds of Words, Thanhhà Lai gave me a clue. She describes herself as a voice-driven writer and she relates the effort she went through to find the voice of Hà, Mai, Hằng and LeeRoy. Each is portrayed in ways that give readers the chance to go inside the characters’ minds through their language and understand what motivates and drives them to act the way they do. Through word choice and sentence structure she captures the voice of a 10-year-old Vietnamese girl by writing English in a way that sounds like you are thinking in the tonal poetic Vietnamese language. By the end of Inside Out & Back Again, we know who she is and what actions she takes, and we also understand what is inside her mind, how she thinks, what she smells, what she notices, what she does. Lai uses voice to capture the challenges of languages, cultural clashes, and the humor that helps carry her characters (and readers) through to the hopeful endings.

A sequel to Inside Out & Back Again is in process. Hà is two years older, and I can hardly wait!

Authors’ Corner is a periodic profile featured on our blog where authors discuss their writing process and the importance of school visits. Worlds of Words frequently hosts these authors for events in the collection. To find out when we are hosting an author, check out our events page.

- Themes: Butterfly Yellow, Inside Out and Back Again, Susan Corapi, Thanhha Lai

- Descriptors: Authors' Corner