By Deanna Day, Washington State University, WA, and Barbara A. Ward, University of New Orleans, LA

In this column we continue to explore recent trends in censorship and book banning by highlighting how authors feel about their books being challenged. Additionally, we offer some ideas for classroom teachers interested in supporting children’s rights to read by teaching about censorship and book banning.

In this column we continue to explore recent trends in censorship and book banning by highlighting how authors feel about their books being challenged. Additionally, we offer some ideas for classroom teachers interested in supporting children’s rights to read by teaching about censorship and book banning.

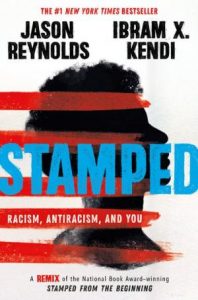

It isn’t just teachers, librarians, and school board members who are put into the position of defending certain books. The recent attacks on books featuring certain types of stories have even had a chilling effect on the publishing industry, with some publishing houses shying away from topics that might be deemed controversial. Many authors of children’s and young adult books are finding themselves on the defensive because their books have drawn negative attention from parents and community members. Author Jason Reynolds, who has written a number of books that have been challenged such as Stamped: Racism, Antiracism and You (2020), a remix of the adult title Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America (2016) by Ibram X. Kendi and All American Boys (2015), cowritten with Brendan Kiely, emphasizes that limiting access to books limits kids’ curiosity and that banning books sends the message that kids shouldn’t ask questions. “Books don’t brainwash. They represent ideas,” he said.

Like Reynolds, we consider books to be one of the best places for children and teens to explore hard topics and complicated issues, offering starting points for honest conversations and providing material with conflicting points of view worthy of discussion. They also foster critical thinking and questioning while enabling young readers the chance to simply wonder or engage with ideas. Instead of fearing and avoiding the uncomfortable or potentially controversial conversations young people might bring up during or after a reading, we need to encourage these discussions. We most likely won’t agree about everything we encounter in books or every idea expressed by an author, but all questions and ideas deserve to be articulated and explored. Reynolds has even maintained that adults who want to eliminate access to books don’t believe children are mature or intelligent enough to have difficult conversations and most likely avoid these complicated conversations. Nothing could be further from the truth. Educators and parents need to give young readers credit for their ability to do so. In our own classrooms—from elementary to middle school to high school—we have seen plentiful evidence that youngsters are sometimes more willing to explore complex topics than some college students.

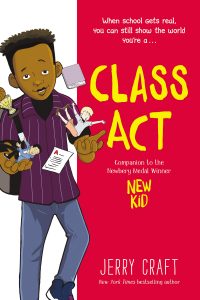

Cartoonist and author Jerry Craft, who wrote and illustrated New Kid (2019), which has also landed on the Frequently Challenged Book List maintained by the American Library Association, shared on NPR that he wrote this award-winning graphic novel to give Black kids’ hope and an example of a bright future. He was surprised when Texas and Pennsylvania school districts challenged his Newbery winner, claiming that it taught critical race theory. He wrote the first book that is now part of a series—Class Act (2020) and School Trip (2023)—because many Black protagonists experience life-changing or catastrophic events, and he wanted to depict a counternarrative. Instead of violence, drug trafficking, police violence and incarceration, his books are about growing up, making friends, and going on class trips.

Cartoonist and author Jerry Craft, who wrote and illustrated New Kid (2019), which has also landed on the Frequently Challenged Book List maintained by the American Library Association, shared on NPR that he wrote this award-winning graphic novel to give Black kids’ hope and an example of a bright future. He was surprised when Texas and Pennsylvania school districts challenged his Newbery winner, claiming that it taught critical race theory. He wrote the first book that is now part of a series—Class Act (2020) and School Trip (2023)—because many Black protagonists experience life-changing or catastrophic events, and he wanted to depict a counternarrative. Instead of violence, drug trafficking, police violence and incarceration, his books are about growing up, making friends, and going on class trips.

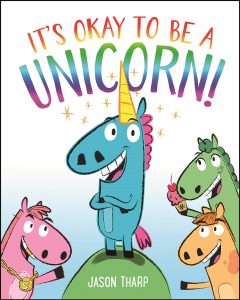

Another author interested in making sure that youngsters with some sort of perceived imperfection had his work attacked for the oddest of reasons. Jason Tharp, who wrote and illustrated It’s Okay to Be a Unicorn (2020), faced a parental complaint over its rainbow illustrations. Because he was often bullied as a child, he wanted youngsters with glasses, a lisp or those who feel different to feel more visible, less marginalized and more secure. There are plenty of rainbows in the picture book but no LGBTQIA+ references. Despite the parent’s concern, Tharp’s appearance to read his unicorn book at a Columbus, Ohio school, went as planned. Although Tharp was shocked about the kerfuffle, he says he will continue to write books that speak to youngsters who feel alone, lost, or even weird.

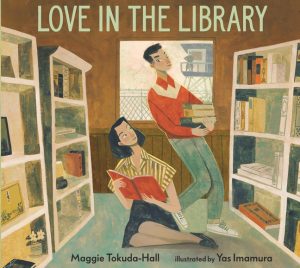

Some authors are even being asked to revise or cut questionable topics from their books. For instance, Maggie Tokuda-Hall wrote the picturebook Love in the Library (2022) about a love story that takes place in a U.S. WWII internment camp. Scholastic Books sought a licensing agreement and wanted to re-package the book for classrooms. The publishing company asked if they could cut a paragraph and remove the word “racism” from her author’s note. When Tokuda-Hall refused, Scholastic decided not to publish the book for the school market.

Some authors are even being asked to revise or cut questionable topics from their books. For instance, Maggie Tokuda-Hall wrote the picturebook Love in the Library (2022) about a love story that takes place in a U.S. WWII internment camp. Scholastic Books sought a licensing agreement and wanted to re-package the book for classrooms. The publishing company asked if they could cut a paragraph and remove the word “racism” from her author’s note. When Tokuda-Hall refused, Scholastic decided not to publish the book for the school market.

Judging from these examples, clearly, things are getting out of hand, and intellectual freedom is under attack. In response to these disturbing trends, more than 1,300 children’s book authors signed a letter to Congress in 2022, condemning book bans in libraries and schools. The letter is signed by well-known authors such as Rick Riordan, Mo Willems and Judy Blume. In part, the letter says: “When books are removed or flagged as inappropriate, it sends the message that the people in them are somehow inappropriate. It is a dehumanizing form of erasure. Every reader deserves to see themselves and their families positively represented in the books in their schools.”

All educators, librarians and community members must fight for young readers to be able to read freely, thus protecting their intellectual freedom and right to question. Furthermore, it’s essential to consider the importance of equity and inclusion, part of learning how to respect and live together. Why? Often, bigotry stems from ignorance or lack of familiarity with some of this nation’s founding principles. Although it’s important to be mindful of intellectual freedom and the perils of book banning throughout the year, perhaps the most important action that all of us can take is to observe Banned Book Week each year. Held annually in the fall, usually in late September or early October, this event gives us a chance to highlight some of the books that have been challenged or banned in the past while celebrating the free exchange of ideas. Launched in 1982 by the American Library Association in response to a surge in book challenges, this year’s celebration is October 1-7 with the theme of “Let Freedom Read!” Observing Banned Book Week can help students and families become aware of the book challenges that are occurring every day. Emphasizing and helping children understand their rights and how they can fight censorship is important.

All educators, librarians and community members must fight for young readers to be able to read freely, thus protecting their intellectual freedom and right to question. Furthermore, it’s essential to consider the importance of equity and inclusion, part of learning how to respect and live together. Why? Often, bigotry stems from ignorance or lack of familiarity with some of this nation’s founding principles. Although it’s important to be mindful of intellectual freedom and the perils of book banning throughout the year, perhaps the most important action that all of us can take is to observe Banned Book Week each year. Held annually in the fall, usually in late September or early October, this event gives us a chance to highlight some of the books that have been challenged or banned in the past while celebrating the free exchange of ideas. Launched in 1982 by the American Library Association in response to a surge in book challenges, this year’s celebration is October 1-7 with the theme of “Let Freedom Read!” Observing Banned Book Week can help students and families become aware of the book challenges that are occurring every day. Emphasizing and helping children understand their rights and how they can fight censorship is important.

During this week teachers and librarians can share and discuss the contents of the First Amendment with students and talk about their rights to read. We believe that teachers and librarians must have open dialogue about the many book challenges. We can invite students to read picturebooks or novels that have been challenged and empower them to fact-find and decide why they think the titles have been challenged. We also can ask students to critically explore the different views on the books, thinking about the impact or harm of each book, discussing why or why not a book should be kept on shelves.

Organizing literature circles or book clubs may be the easiest way to introduce intellectual freedom to children and families. Hosting family book discussions will help build relationships with students and communities. Teachers can select book titles that have been removed from library or classroom shelves for students and their families to read and then encourage them to figure out why the title has been challenged. Amina Akram, co-creator of Ouraan, also suggests that teachers send home family letters or guides with each book to let them know about sensitive themes or topics and give them conversational tools about how to talk with their child. When the family has read the challenged book, they can write a testimonial describing what they learned and why they think others should read the text. Families can gather for literature discussions at school and share their testimonials.

Organizing literature circles or book clubs may be the easiest way to introduce intellectual freedom to children and families. Hosting family book discussions will help build relationships with students and communities. Teachers can select book titles that have been removed from library or classroom shelves for students and their families to read and then encourage them to figure out why the title has been challenged. Amina Akram, co-creator of Ouraan, also suggests that teachers send home family letters or guides with each book to let them know about sensitive themes or topics and give them conversational tools about how to talk with their child. When the family has read the challenged book, they can write a testimonial describing what they learned and why they think others should read the text. Families can gather for literature discussions at school and share their testimonials.

Perhaps it’s best for educators to inform themselves about intellectual freedom and the right to read before they begin choosing books for their curriculum or even shared reading. Knowing the history of book banning and censorship efforts as well as having the tools to combat them is essential. Pat R. Scales’ book, Teaching Banned Books: 32 Guides for Children and Teens, and Suzanne Linder and Elizabeth Majerus’s book Can I Teach That?: Negotiating Taboo Language and Controversial Topics in the Language Arts Classroom are recommended starting points since they offer suggestions about how to justify the use of various books as well as ideas about how to use them in the classroom. After perusing these titles, teachers may want to refer to some of the successful pedagogical practices described in various journals and online platforms.

Winkler (2005), for instance, suggests that teachers who teach older grades incorporate mock trials in which students select a role–school administrator, community member or student–and make a list of 12 reasons why a particular book should be restricted, banned or retained. Students present their positions to the entire class, which acts as the school board and votes on the outcome of the book. Students can be assessed on delivery, preparation and knowledge of the book. Having critical discussions with students about why people want to protect others from material they view as dangerous or immoral can be beneficial for older students.

Another writer and educator, Lisa Storm Fink uses persuasive writing as a tool to explore book banning. Students write persuasive letters or essays for the School Board in order to share their perspectives after reading a challenged book and identifying why they think it has been banned. By doing so they form an opinion about what should be done with the book, reference the First Amendment, even sometimes crafting a rebuttal or opposing viewpoints.

Liou and Diets Cutler (2023) suggest that student voices need to be heard on challenged and banned books, but they caution that schools, teachers and librarians need to proactively solicit students’ voices prior to book challenges. These authors believe that we need to give students many opportunities to choose the books they want to read, choose the curriculum they want to learn as well as learn how to talk to others in multiple ways with partners, groups, surveys, voting and debates. Students also need numerous opportunities for discourse in order to understand that free exchange of ideas, even conflicting ones, are a tenet of democracy. All K-12 students need to participate in literature discussions and restorative circles so that they learn how to talk, disagree, listen, and speak up for their rights as readers. This is especially true today as various civil liberties and intellectual freedom seem increasingly in peril.

Liou and Diets Cutler (2023) suggest that student voices need to be heard on challenged and banned books, but they caution that schools, teachers and librarians need to proactively solicit students’ voices prior to book challenges. These authors believe that we need to give students many opportunities to choose the books they want to read, choose the curriculum they want to learn as well as learn how to talk to others in multiple ways with partners, groups, surveys, voting and debates. Students also need numerous opportunities for discourse in order to understand that free exchange of ideas, even conflicting ones, are a tenet of democracy. All K-12 students need to participate in literature discussions and restorative circles so that they learn how to talk, disagree, listen, and speak up for their rights as readers. This is especially true today as various civil liberties and intellectual freedom seem increasingly in peril.

When young people show up at a school board meeting to talk about books being challenged, this adds to the impact of those who want to keep certain books off library shelves. For example, when hundreds of students, parents and residents in York County, Pennsylvania protested limits on books from the perspective of gay, Black and Latino children, they won. The challenged materials remained in use.

Nowadays parents and political groups such as Moms for Liberty are typically the ones who challenge many books. Pen America learned in a 2022 poll that 41% of the bans in a six-month period were declared by state officials or elected lawmakers, not parents or caregivers. Politicians may be demanding the removal of so many books to polarize communities, prompting concern and fear in order to help them gain votes and win elections. These politicians are also undermining public education, public libraries and the public good to gain power.

Concerned community members can also speak up about book banning. In Orlando, Florida, a 100-year-old woman voiced her thoughts by creating a quilt of some of the books that have been targeted and then appeared at her local school board meeting. Parents and community members need to attend school board and library board meetings to thank them for everything that they do for children and how they support democracy. Their presence also allows them to share that they want their children to have a quality education with books that help them understand diverse peoples and many resources to learn about our nation’s history with its progresses but also its mistakes. Let school boards know that you advocate for books that talk about tough issues because you want children to build empathy and see situations through the eyes of people different from them. In addition, we can also purchase banned books, request banned books at libraries, and read challenged books. But most of all we must vote for those who are advocates for first amendment rights. There are grassroots organizations such as Red Wine & Blue that have online Troublemaker Trainings to help parents testify at a school board hearing, write a press release and file a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. Book supporters often resort to creative efforts to highlight these books. One library in the New Orleans area even has a banned book bingo activity in which patrons fill their cards based on the banned or challenged books they read. Clearly, there are movements afoot to thwart those who would silence certain authorial voices and perspectives. There is hope but only if we think, speak, and act.

We close this blog post with some recent children’s books that discuss censorship and book banning. All books deserve a place on the shelves of libraries and classrooms. These particular titles could be used to discuss the issue and inform students about their First Amendment rights.

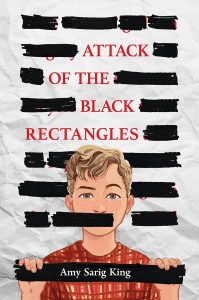

Attack of the Black Rectangles by Amy Sarig King (2022) highlights the actions of a group of sixth graders who realize the novel they are reading and discussing in literature circles has “black rectangles” or certain words and passages that have been covered up with black sharpie. The youngsters want to know who has censored their books. First, they obtain a pristine copy of the book that has no blacked out words. Then, they complain to their school principal and later protest at a school board meeting. These young activists stand up for their rights to read. Through the actions of various characters, readers realize the complexity of book censorship and the possible motives of would-be censors.

Attack of the Black Rectangles by Amy Sarig King (2022) highlights the actions of a group of sixth graders who realize the novel they are reading and discussing in literature circles has “black rectangles” or certain words and passages that have been covered up with black sharpie. The youngsters want to know who has censored their books. First, they obtain a pristine copy of the book that has no blacked out words. Then, they complain to their school principal and later protest at a school board meeting. These young activists stand up for their rights to read. Through the actions of various characters, readers realize the complexity of book censorship and the possible motives of would-be censors.

Banned Book Club by Kim Hyun Sook, Ko Hyung-Ju and Ryan Estrada (2020) is a historical memoir about Sook’s experiences in an underground banned book club at college. This YA graphic novel discusses political oppression in South Korea in the early 1980s. Sook’s parents feared that college would change her, which is exactly what happens. She finds her voice and becomes involved in protests against the government. Because the book takes place in South Korea, reading about intellectual freedom or the lack of it will enable readers to realize how important this country’s First Amendment rights truly are.

Banned Book by Jonah Winter and Gary Kelley (2023) describes a group of people called “We Are Right” or WAR that black out words in books because they consider them to be inappropriate for children. These warriors show up at school board meetings or local schools demanding that certain book titles are removed from libraries. Throughout the picturebook there are phrases and words that are blacked out to show readers what the warriors are attacking. Even though a librarian stands up for the students’ rights to read these books, they are whisked away and thrown into the town landfill, a chilling prediction of a possible future for books deemed problematic in the future. For more on Jonah Winter, see his Author’s Corner.

This Book is Banned by Raj Halder and Julia Patton (2023) humorously showcases what happens when censorship occurs in schools and libraries. Just because we don’t like something, such as giraffes or avocados, doesn’t mean that everyone feels the same and they should be banned. This would make a good read aloud for students to discuss how each of us has different beliefs and whether our beliefs should infringe on others. For example, if one child is scared of the big bad wolf, should the wolf be banned from books for all kids? If we continue to ban or reject books, our library and classroom shelves may eventually be empty.

Next week we will be writing about pushing back against the current wave of book challenges.

References

Liou, D. D. and Deits Cutler, K. (2023). A framework for resisting book bans. Educational Leadership, 80(5), 48-53.

Linder, S., & Majerus, E. (2016). Can I teach that? Negotiating taboo language and controversial topics in the language arts classroom. Lanham: Rowan & Littlefield.

Scales, P. (2019) Teaching banned books: 32 guides for children and teens. Second Edition. Chicago: American Library Association.

Winkler, L. K. (2005). Celebrate Democracy! English Journal, 94(5), 48-51.

WOW Currents is a space to talk about forward-thinking trends in global children’s and adolescent literature and how we use that literature with students. “Currents” is a play on words for trends and timeliness and the way we talk about social media. We encourage you to participate by leaving comments and sharing this post with your peers. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit its archival stream.

- Themes: Amy Sarig King, Attack of the Black Rectangles, Banned Book, Banned Book Club, Barbara A. Ward, Can I Teach That?, Deanna Day-Wiff, Elizabeth Majerus, Gary Kelley, Ibram X. Kendi, It's Okay to Be A Unicorn, Jason Reynolds, Jason Tharp, Jerry Craft, Jonah Winter, Julia Patton, Kim Hyun Sook, Ko Kyung-Ju, Love in the Library, Maggie Tokuda-Hall, New Kid, Pat R. Scales, Raj Halder, Ryan Estrada, Stamped, Stamped from the Beginning, Suzanne Linder, Teaching Banned Books, This Book is Banned

- Descriptors: Debates & Trends, WOW Currents

This is a really great resource about banned books and how important children’s literary freedom is extremely important. I really appreciate the list that was at the end of the article of books about this topic as it provides a platform so these books do not become forgotten.

Hi! I loved this article so much, it helped me understand some very important points and what some authors say about book banning.

I was wondering what are some of your thoughts about explicit themes in books that are challenges and/or banned? I am doing a project on explicit themes in children’s literature / juvenile fiction and patterns that show up on this topic.

I read Attack of the Black Rectangles in a college course, and had the pleasure of meeting the author through a zoom meeting. She said the book was based on a true story and that, from her experience, students are the most effective party at combatting book bans. I wonder if the fact that the students are the ones challenging authority is a large factor in the book’s censorship.

I was surprised to hear about the quilter from Florida! Thank you for sharing her story and expanding on the immense importance of advocacy against book banning! 🙂

Hello,

I really enjoyed your article. The quote you included from Jason Reynolds, “Books don’t brainwash, they represent ideas.” Really stuck out to me. The books discussed in this article almost all discuss the act of book banning or subjects that have been quickly banned, which is not surprising but still jarring to see outlined. In what ways can students at all levels and educators advocate for this to stop in places where it is more prevalent?

After reading attack of the black rectangles it gave me thought about these books. Giving me insight about these books and problems. They teach you about what happens.

I would be interested in “It’s okay to be a unicorn” because the book itself wasn’t censored but a word in the author’s note. I also think the approach to the topic of the book is interesting and engaging for children in a way they could understand.

This website is such a great resource for educators and readers who are just starting out. I appreciate how it brings attention to important issues like children’s right to read while also offering practical ideas and discussions. It’s clear that the content is designed to support both teachers and students in meaningful ways.

I loved this article it does a great job highlighting the harmful effects of book banning while also offering practical ways for teachers and families to support children’s right to read my favorite was the its okay to be a unicorn. I especially liked the mix of author perspectives and classroom strategies that show how communities can stand up for intellectual freedom. It’s both informative and inspiring.

I think it’s interesting that a book can be banned because of something in the author’s note. That’s ridiculous. I like that the author of “It’s Okay to Be A Unicorn” refused to change her author’s note.

Hi there,

This is such a powerful and impactful article considering the times we are in! Thank you for highlighting so many strategies to defend children’s right to read. It helps a lot of us newbie activists with banned books. I really like the passion you had for giving students a voice through literature circles and open dialogue.

One question I’m curious about is in schools or communities where censorship pressure is high, what are some of the most effective “low-risk” first steps that teachers, librarians, or parents can take to begin supporting the voices of our children?

I am currently taking a class at my university about banned books and have read the book “Attack of the black rectangles”. The book was terrific, and we should definitely place more emphasis on the issue of banning books, especially in places where the ban is worsening, such as Texas and Florida. We are planning ways to be more of an activist and would like to know how college students like myself can contribute to addressing this situation.