by Kathy Short, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ

One of the lessons that I have learned as a reader of global literature is to never read a book by itself–to always read a book alongside other books. Over and over, I find that our interpretations and connections change dramatically when we read paired books or read a book within a larger text set or collection. Throughout the next month, my blogs will focus on my experiences of reading books alongside each other, most recently within a graduate course on global literature.

One of the lessons that I have learned as a reader of global literature is to never read a book by itself–to always read a book alongside other books. Over and over, I find that our interpretations and connections change dramatically when we read paired books or read a book within a larger text set or collection. Throughout the next month, my blogs will focus on my experiences of reading books alongside each other, most recently within a graduate course on global literature.

This blog focuses on an example of how our perspectives on a book can change dramatically when we read it within a broader collection. Mirror, written and illustrated by Jeannie Baker (2010), is an Australian picture book that is receiving enthusiastic reviews as visually stunning with a thoughtful message of global interdependence. As an individual piece of literature, this picture book is exemplary and deserving of awards and recognition as an aesthetic masterpiece. When considered within the political structures of our society and the broader collection of children’s books, however, the book is problematic and raises provocative questions about the responsibilities of authors, reviewers, and readers.

Continue reading

Sometimes when colleagues who are insiders to a culture talk about small details of inaccuracies in particular children’s books, like the kimono being folded wrong or the atypical hairstyle of a character, my immediate response is to think, “Okay, I can see your point but aren’t you being a bit picky?” I want to point out that the bigger themes in the book are more significant and that differences exist within a culture, so that what seems like an error to one insider is considered appropriate by another. Even cultural insiders sometimes get these details wrong. I reminded of Yoo Kyung Sung’s conversation with a Korean American author whose young adult novels have won major awards, but who uses Korean terms in how the brother and sister address each other that are incorrect and that infer a feminization of the brother that is not intended. The author’s reply was that Koreans always point that out, and that she didn’t realize the terms were incorrect—they were the ones used in her family who had been in the U.S. for several generations.

Sometimes when colleagues who are insiders to a culture talk about small details of inaccuracies in particular children’s books, like the kimono being folded wrong or the atypical hairstyle of a character, my immediate response is to think, “Okay, I can see your point but aren’t you being a bit picky?” I want to point out that the bigger themes in the book are more significant and that differences exist within a culture, so that what seems like an error to one insider is considered appropriate by another. Even cultural insiders sometimes get these details wrong. I reminded of Yoo Kyung Sung’s conversation with a Korean American author whose young adult novels have won major awards, but who uses Korean terms in how the brother and sister address each other that are incorrect and that infer a feminization of the brother that is not intended. The author’s reply was that Koreans always point that out, and that she didn’t realize the terms were incorrect—they were the ones used in her family who had been in the U.S. for several generations. The need for book reviewers who are either cultural insiders or who consult with cultural insiders in writing their reviews has become increasingly apparent to me. Seemi Aziz Raina and Yoo Kyung Sung in their research on the representations of Muslims and Korean Americans in children’s literature have identified many subtle issues that would be difficult to identify by someone who does not have some kind of insider knowledge. They have also found that the recency of that insider knowledge is critical.

The need for book reviewers who are either cultural insiders or who consult with cultural insiders in writing their reviews has become increasingly apparent to me. Seemi Aziz Raina and Yoo Kyung Sung in their research on the representations of Muslims and Korean Americans in children’s literature have identified many subtle issues that would be difficult to identify by someone who does not have some kind of insider knowledge. They have also found that the recency of that insider knowledge is critical. Book reviews, by definition, are a summary and evaluation of a particular book. Clearly reviewers make those evaluations within their in-depth knowledge of the broader field and body of literature. The reviews themselves sometimes connect the book to other literature, especially in longer reviews, but the general approach to reviewing is from an individualistic standpoint — the book stands alone. Several recent examples have made evident why this is problematic.

Book reviews, by definition, are a summary and evaluation of a particular book. Clearly reviewers make those evaluations within their in-depth knowledge of the broader field and body of literature. The reviews themselves sometimes connect the book to other literature, especially in longer reviews, but the general approach to reviewing is from an individualistic standpoint — the book stands alone. Several recent examples have made evident why this is problematic. Having written book reviews for various publications, I am aware of the difficulty of succinctly conveying a summary of the text, description of the illustrations, discussion of themes, and evaluation of the book in a few sentences. Many book reviews are one short paragraph, providing little space to convey much of a sense of the book. My conversations with other educators over the past several months have led me to wonder about the unwritten rules for writing these reviews that have developed out of a need to be so brief. I wonder if we have fallen into some practices as reviewers that send unintended messages to the mainstream audience for reviews.

Having written book reviews for various publications, I am aware of the difficulty of succinctly conveying a summary of the text, description of the illustrations, discussion of themes, and evaluation of the book in a few sentences. Many book reviews are one short paragraph, providing little space to convey much of a sense of the book. My conversations with other educators over the past several months have led me to wonder about the unwritten rules for writing these reviews that have developed out of a need to be so brief. I wonder if we have fallen into some practices as reviewers that send unintended messages to the mainstream audience for reviews. My major goal for teachers taking my course on multicultural literature this semester was to encourage them to develop a critical lens to use in reading and evaluating literature.

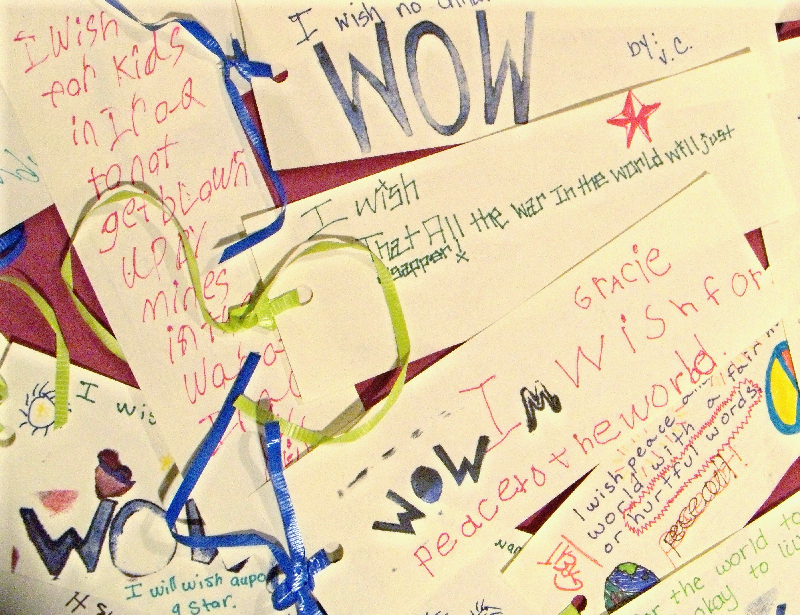

My major goal for teachers taking my course on multicultural literature this semester was to encourage them to develop a critical lens to use in reading and evaluating literature.  Many adults believe children should not be burdened with books that raise difficult social issues, particularly war and violence. They argue to protect the innocence of children, not realizing that what children want is perspective, not protection.

Many adults believe children should not be burdened with books that raise difficult social issues, particularly war and violence. They argue to protect the innocence of children, not realizing that what children want is perspective, not protection.