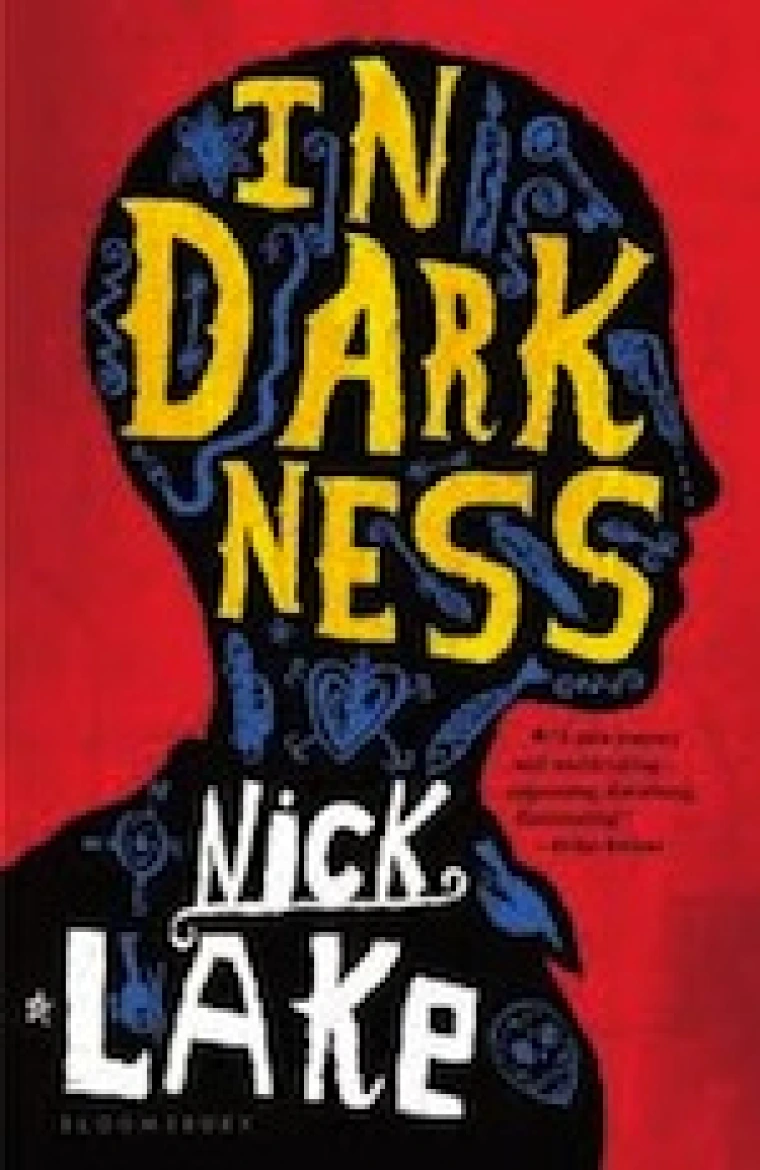

In Darkness

In the aftermath of the Haitian earthquake, fifteen-year-old Shorty, a poor gang member from the slums of Site Soleil, is trapped in the rubble of a ruined hospital, and as he grows weaker he has visions and memories of his life of violence, his lost twin sister, and of Toussaint L'Ouverture, who liberated Haiti from French rule in the 1804.

See the review at WOW Review, Volume 4, Issue 3

9781599907437

Genre:

Realistic Fiction