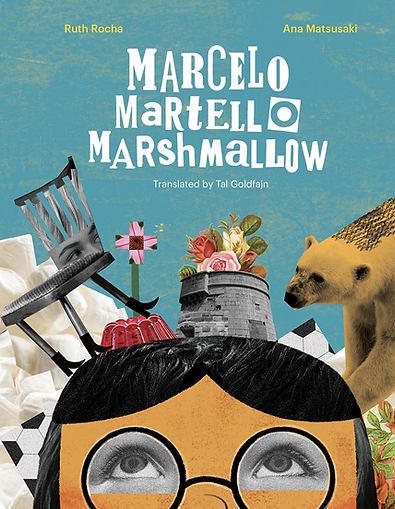

Marcelo Martello Marshmallow

Marcelo Martello Marshmallow

Written by Ruth Rocha

Illustrated by Ana Matsusaki

Translated by Tal Goldfajn

Tapioca Stories, 2024, 36pp [unpaged]

ISBN: 978-1734783995

This translated book from Brazil features a child who asks questions and creatively acts on aspects of his world that do not make sense to him. What he finds most puzzling is the randomness of words. He starts by questioning his name and then goes on to question the words assigned to objects and animals, such as table, chair, and hair. His parents grow tired of his questions, but their answers do not satisfy Marcelo. He decides to create his own words that he feels are a better fit, like calling a chair by the term ‘seater’ and a spoon as ‘scrambler.’ His parents are embarrassed when guests visit and worry about school, but Marcelo continues developing his own language. When Marcelo’s invented language is not understood by his parents, the doghouse burns (the dog is safe). Marcelo complains with frustration that grown-ups do not understand him, and so the parents decide to communicate with him in his language rather than forcing him to conform to adult terminology. The book ends years later with Marcelo’s daughter asking, “Why is a table named table?”

This picturebook is creative both in Marcelo’s invented language and in the translation process. The original book title in Portuguese is Marcelo, Marmelo, Martelo, names that Martelo plays with as possibilities for himself. In Portuguese, marmelo means ‘quince,’ a golden, fragrant fruit used to make jams, so the translation decisions were difficult since using quince would ruin the language play. The translator made the decision to use marshmallow to preserve the language play, since that is central to the book. Martelo in Portuguese means ‘hammer’ but that is changed to Martello in the English translation which is the name of a tower. These shifts in translation to preserve the language play meant that the book needed to be re-illustrated to bring in marshmallows instead of the fruit and a tower instead of a hammer.

The book, originally released in 1976, is considered a classic read in schools all over Brazil and was made into a television series (see the cover and the TV promotion). That book contains three short stories of children, one of which is Marcelo’s story. The original illustrator, Adalberto Cornavaca, used cartoon-style illustrations for the short story, highlighting the main actions in small spot illustrations. The translated book features new full-page illustrations by Ana Matsusaki, who uses a surrealistic style in which fragments of photos are incorporated into each scene, especially the eyes and hands of characters.

Themes of creativity and imagination are highlighted along with word play and child agency. The ending is notable in that the expected ending of Marcelo realizing that he needs to use socially conventional words to communicate is upended by the parents honoring their child’s frustration with grown-ups who do not “understand anything about anything at all.” His father replies, “Please don’t be sad, my dearest boy. We’ll build a new dogstayer for Barky.” Although the parents do not learn to speak exactly like Marcelo, they do “try very hard to understand what he says” and they no longer care what their guests think, honoring their child’s curiosity and creativity.

Another possible interpretation relates to the time period in which this book was originally published in Brazil. Since Brazil was under a military dictatorship at the time, free speech was limited and many writers expressed dissent in subtle ways. Although this book is not explicitly political, Marcelo’s act of redefining reality and creating his own vocabulary can be read as a metaphor for resisting imposed norms and censorship. To highlight the theme of subtle resistance, this book could be read alongside The Composition by Antonio Skármeta and Alfonso Ruano (2000), about a government contest for children to write about what their family does at night, based on a dictatorship in Chile.

Other possible pairings are books that celebrate word play and vocabulary, such as A Chest Full of Words by Rebecca Gugger and Simon Sothlisberger, translated from German by Lawrence Schmiel (2025). The translator faced a similar problem in that words that flow from the chest had to be translated to words that are expressive in English in similar ways to the original German. Since these words are integrated into the illustrations, the illustrations had to be revised. What Makes Us Human by Victor D.O. Santos and Anna Forlati (2024) was originally published in Brazil and uses a riddle format to explore language as the cornerstone of human identity and connection.

This picturebook could also be connected to books that depict child agency especially with adults, such as Fred Stays with Me by Nancy Coffelt and Tricia Tusa (2007) in which a child, who splits her time between her father’s and mother’s houses, tells her parents that her dog is the constant in her life and they do not decide if she can keep the dog. The Rock in My Throat by Kao Kalia Yang and Jiemei Lin (2024) is the story of a Hmong child who asserts her agency by refusing to speak English, the language of impatience and rudeness, in school to reply to teachers, while fluently speaking Hmong, a language of beauty, at home with her family. Head in the Clouds by Rocio Araya (2024) is translated from Spanish and features a child whose teacher complains is always daydreaming with her “head in the clouds” instead of paying attention. In response to the teacher’s criticism, Sofía shares the many questions that fill her mind. Color-filled images from Sofía’s vibrant mind are depicted in contrast to the teacher’s monochromatic dull-gray mind.

This picturebook was named to the 2025 Outstanding International Books, an award that Ruth Rocha received in 2017 for her translated book, Lines, Squiggles, Letters, Words (2016). Ruth Rocha is a beloved and acclaimed Brazilian author who is viewed as leading a new wave of Brazilian children’s literature with her articles and books. She is particularly known for her playful storytelling and her focus on children’s curiosity. Marcelo, Marmelo, Martelo (1976) was her second children’s book. She received the Charge to Cultural Merit from Brazil’s president along with other prestigious literary prizes. She has published 130 books, translated into 500 editions and more than 25 languages.

The illustrator, Ana Matsusaki, is from São Paulo with a degree in graphic design. She worked as an art director before deciding to commit herself full-time to illustration and book design in her own studio. Her work has been selected for inclusion at the Biennial of Illustration Bratislava and the Bologna Children’s Book Fair. The Collector of Heads (2023) was her debut book, originally published in Brazil and translated into English and Spanish, about a girl who collects heads, histories, and memories of those who have died.

Tal Goldfajn is a linguist, translator, and translation scholar who is an assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst in the Spanish and Portuguese Studies department. Along with her students at UMass Amherst, she founded the Pipa Project initiative for the promotion of translated children’s literature and multilingual storytelling. She is working on a book titled Translation and Inheritance, for the Routledge series New Perspectives in Translation and Interpreting Studies. She translates books and articles in Spanish, English, Portuguese, French, and Hebrew.

Kathy G. Short and Christiane Pontes Pimental de Andrade, University of Arizona

© 2025 by Kathy G. Short and Christiane Pontes Pimental de Andrade