Making Connections Matter

by Lenny Sánchez, Dara Bradley, and Jessi Spinder Menold.

The phrase “making connections” immediately calls to mind the popular triad of text-to-self, text-to-text and text-to-world connections. It would not be unusual to walk into a classroom in almost any school across the country and see a poster of these reading strategies tacked up on a wall. Without question, they deserve respectable recognition. Making connections, after all, is what allows reading to become personally meaningful. Louise Rosenblatt (1978) describes how a person’s life experiences are what enable a text to be accessible and entered into by readers. Experiences break the boundary between the reader’s world and the world of the text. Making connections seems to be at the heart of the answer to Rosenblatt’s question, “What is the reader’s starting point?”

Our Group Goals as Educators

As a group of high school teachers, a principal, a media specialist, and a university professor, we came together as a literacy community for a year-long inquiry and found ourselves returning to this query, growing ever more curious about the role that making connections has for reading and beyond. We began to wonder whether we were teaching this strategy cursorily, even though we recited it frequently in our conversations with students. At its core, what does making connections really mean?

Our group met at an alternative secondary school in Columbia, Missouri where all of the teachers and participating principal worked. The school served around 200 students in grades 9-12, who attended the school because the traditional school system did not support them well. The school was designed to provide work-study experience, GED preparation, and career readiness in addition to its challenging academic program.

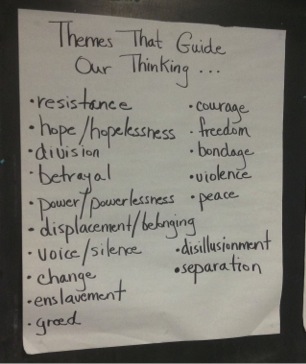

Our initial group goals focused on addressing literature instruction through an interdisciplinary stance and to nurture global awareness through literature studies. Although the teachers and principal were either new or fairly new to the alternative high school, they shared a justice-orientated approach to teaching and a desire to restructure the curricular divides between the English and Social Science disciplines. They wanted to co-construct course outcomes so that whether students were studying Pompeii or prepositional phrases, they could engage in similar cross-classroom learning experiences such as open exchange and perspective-sharing. For example, as students read the novel Sold (McCormick, 2008) in both their English and Social Studies classrooms, they dealt with questions of: “Whose voices are heard and whose voices are silent? What is the evidence of power? Where are the eyes of resistance seen? How do themes of freedom and bondage surface?” Teachers and students relied on powerful questions such as these, which hung on chart paper in the classrooms, to unveil assumptions, explore point of view, and reflect on relevance to their own situations across both classroom contexts. Photo 1 shows another example of a shared chart created by the teachers, used to support cross-cutting themes found in curriculum across subject areas.

On average, we met once a month as a study group to set curricular goals, select and evaluate literature for classroom use, and share classroom experiences in regards to student discussions and teaching difficulties and surprises. The more we talked and shared about our work during the year, the more we recognized making connections was at the heart of our discussions. In what follows, Dara, an English teacher, describes how one literature study at the beginning of the year, in particular, helped her begin to think more deeply about how connections matter.

Connecting to the World through Book Study: Dara Bradley

As a veteran reading teacher, turned first year high school English teacher, I was trying to find books that students would both enjoy and that would fit into the world literature class curriculum I was expected to cover. More importantly, I wanted students to be able to connect to characters outside of their own understandings of the world. They needed to be able see themselves as living and practicing citizens who belonged to an ever-changing global society. My tenth-grade classroom consisted of “at risk” secondary students who began their school careers in other buildings around the district. Most of them had sat through years of teaching that minimally addressed their day-to-day concerns. I wanted to help them process their own life experiences while opening up opportunities to look at the world differently. I hoped using literature set in global contexts could instill a greater curiosity of the world and confront them with ideas and practices from differing vantage points.

I decided to start with a book that I thought would be out of students’ comfort zones, hoping that getting them used to risk-taking from the beginning of the year might encourage questions and sharing as natural responses to text. As I later recognized, these types of interactions operate as necessary gateways that enable readers to link their experiences to texts and, therefore, gain new perspectives and understandings. I selected Markus Zusak’s (2006) I Am the Messenger as our first book study.

This book is set in an unnamed Australian city where the main character, Ed, age nineteen, inadvertently stops a bank robbery. Subsequently, he receives mysterious tasks that send him around the town with specific instructions to decipher. These tasks intersect him with the lives of strangers and friends with whom he must accomplish meaningful acts of goodness. For instance, he finds himself consoling a lonely elderly woman and a depressed teenage girl, and he repairs a broken relationship between a father and daughter and between two brothers. Over time, he gains confidence that he can accomplish anything and recognizes that he has the ability to change lives. Ed, in fact, transforms his own life from one burdened with discouragement and bad luck to one that illustrates how the smallest deeds make the world a better place.

I divided the book into sections to engage the class with the text through read alouds, whole group readings, and independent reading. Together, we explored conventional literary elements such as foreshadowing, flashback, subplots and dialect along with our interpretations and connections with the book. Students also experimented with developing narrative writing as they examined Zusalk’s writing strategies and craft.

As we read, students began sharing topics of interest they wanted to further study such as language variances and the cross-cultural commonality of what it means to be an underdog. These interests surfaced through “aha” moments when students either suddenly understood something they did not know before or when they began drawing parallels between their lives and the life of Ed.

This book was the first time that these students had been exposed to Australian dialects, which piqued an interest in learning more about the language differences between Australian English and American English. Discussions led to investigations on cultural dialects to further reflect on how people form assumptions based upon how one talks. The students shared stories of judgment that they had experienced and spoke about their initial reactions to Ed’s speech.

Moving beyond language and dialect, several students shared an interest in learning more about Australia as a national entity so we stopped reading and writing for a short while to engage in research. We hopped on computers to gather information on Australian culture and society. Looking back at this decision, I am so thankful we took a “break” from reading in this way. Matt, for example, wanted to learn more about a barefoot soccer game in the book called sledge game. He wondered if it was another name for soccer, rugby, or even a different description for American football. We all researched this topic for part of a day and ended up finding ourselves looking into sports in other countries. I realized that putting the book down literally was an important part of our book study because it gave us the opportunity to appreciate national differences, such as sports, and to examine stereotypes, as with our discussions on dialect, and understand them as superficial knowledge that engenders prejudice. Taking time to nurture these types of connections, ones that might on surface appear to be trivial, enabled students to read more deeply and confront what could otherwise be a conflict of understanding between them and the text.

One of my favorite conversations occurred when students discussed the meaning of “underdog” and valued it as an underlying message of the book. Jevon referenced research he conducted about Australia, sharing “Australians like to root for the underdog because of its history of unjust authority.” His comment, astutely made, certainly confirmed to the class that our observation of the underdog theme was perhaps a correct assessment of the author’s intentions. Although the discussion did not lead into grand inquiries on the early settlements, Indigenous wars, or industrial unrest of Australia, his remark added a new way for us to connect to the text, to imagine the possibility that Ed may represent more than a single person in his desire to live a life free of restraint.

Within these conversations, the class also participated in several discussions about what it means to be a passive member of society versus doing something about the problems one sees within a community. In the book, Ed constantly found himself at this decision point as he witnessed his relationships changing with his friends and relatives. Ed forced us to think about the ways we wanted to participate in our communities and if we would act to make a difference.

Across the book study, dialogue emerged in ways that differed from a regimen where students are forced to relate the text to their experiences as dictated by a predetermined scope and sequence. Rather, there was room for ambiguity. I was excited to see which paths our reading would take, and I was more than pleased to find us on the trails of human values, national past times, and language. I would not suggest that their reading of this text translated into transformative global awareness where they understood the interrelationships between the past, present, and future of global issues. However, their questions and curiosities encouraged them to think critically about the text and to connect creatively in ways that helped them care about the decisions Ed made for his life.

We did not approach the text through equal fascination, but our various interests and experiences invited all of us to engage in the text in unpredictable ways. For example, it was not difficult to recognize that not all students enjoyed focusing on dialects, but our conversations about talk did expose us to being analytical about the language used in the text and to see how Ed was shaped by it.

Final Reflection

Throughout the year, Dara’s class continued reading other novels set in various parts of the world such as In Darkness (Lake, 2012), Slave: My True Story (Nazer & Lewis, 2005), and Saving Francesca (Marchetta, 2006). Each text was connected by a theme centered on teenagers as the protagonists who faced their horrifying pasts or everyday drama. The book studies were often tempered with humor as they addressed life-changing moments.

Very similar types of book studies occurred in the other teachers’ classrooms involved in the year-long inquiry group. The teachers carefully selected texts, including I Am Nujood Age 10 and Divorced (Ali, Minoui, & Coverdale, 2010) and First crossing: Stories about Teen Immigrants (Gallo, 2007), which they hoped would not only expand students’ views of the world but would inspire them to see themselves differently within their own communities. Just as Dara listened closely to her students’ questions and interests, our inquiry group gave attention to our own individual uncertainties and wonders related to using these texts in the classrooms. We considered how to encourage author critique with well-defined assumptions and beliefs, nurture rigorous discussions, and focus on issues of difference while instilling a culture of inclusion. These conversations led us to thinking about the meaning of connections.

As educators, we wanted our students to make connections to texts because we hoped the characters and storylines would provide opportunities for self-reflection as students witnessed how others navigated dilemmas and successes. Although we could not predict exactly how the students would relate to the texts, we organized our teaching so that opportunities could emerge. Just as in Dara’s classroom, students linked themselves to stories through their questions and queries. Giving attention to these through whole-class discussions and time for research allowed their connections to be perceived as more than just an automatic response to a text but as genuine life reflections. In this way, making connections involved an examination of experience, figuring out what was similar and different between one’s perceptions of the world and a world that at times seemed unusual.

In our inquiry group, what we ultimately relearned was that making connections is at the heart of all learning. Not just in reading a text or classroom learning, but in how we relate to one another, develop empathy for what we see, and form a worldview different than our own. Encouraging students to make connections to a text is just a stepping stone to the ways they need to make connections to ideas, people, and circumstances intersecting the world in which they live. Even though we live in a world in which everything seems accessible, we must be diligent in reaching out to make connections.

References

Ali, N., Minoui, D., Coverdale, L. (2010). I am Nujood age 10 and divorced. New York: Broadway.

Gallo, D. (2007). First crossings: Stories about teen immigrants. Somerville, MA: Candlewick.

Lake, N. (2012). In darkness. New York: Bloomsbury.

Marchetta, M. (2006). Saving Francesca. New York: Knopf.

McCormick, Patricia (2008). Sold. New York: Disney.

Nazer, M. & Lewis, D. (2005). Slave: My true story. New York: Public Affairs

Rosenblatt, L. (1978). The reader, the text, the poem: The transactional theory of the literary work. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Zusak, M. (2006). I am the messenger. New York: Knopf.

Dara Bradley is an English teacher at Douglass High School in Columbia, Missouri.

Jessi Spinder Menold is a media specialist teacher at Douglass High School in Columbia, Missouri.

Lenny Sánchez is an assistant professor in literacy education at University of Missouri-Columbia.

WOW Stories, Volume IV, Issue 8 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/iv8.

The journey with Genny and her students has been one of the most powerful experience I ever had with books about Korea. Childhood connections became a powerful tool for children to wake up their curiosity to Korean culture and kids in Korea. Eventually this whole experience let them to think about critical stance of reading. Even though language was not all in English, childhood connection helped them to jump over the huddle in language barrier yet helped them to study carefully other visual cues like illustrations in the Korean picture books in return. This particular story Genny O’Herron wrote is empowering for me as a member of ACLIP indeed.

I can honestly say that I truly enjoyed reading this article. When I search for information on reading within the classroom, the majority of the articles are based around the elementary and middle school aged students. I really appreciate this in-depth discussion of how the teacher helped her students make connections and allowed them to follow the path that the book took them on. I teach at the ninth grade level in all co-teaching classes. My students are mostly not very inquisitive. I believe they have been taught all along to simply read and do the questions. We have lost a lot of the fun in teaching reading and learning about the information in the book. I a very inspired by this classroom and the functionality of the processing of the actual information within the text. We need to teach our students how make those connection and inquire into why things are the way they are. I have always loved to read and have never understand the disdain that many students have for reading. However, I know that if I can get them even slightly interested in the subject matter at hand, then the process is so much smoother. Once again, this was a fantastic article that I will be passing along to my colleagues.

Thanks, I agree that there are few examples of using global literature in secondary school classrooms and there is so much potential at that age level. May kids, however, have learned not to think in schools because not much has been asked of them beyond basic literal level thinking. So while they are capable of so much thinking, they also have a long instructional history of not thinking which we have to get beyond. The potential is there, though, as you point out.