Download as PDF

“I’m Making Changes in My Classroom by Welcoming the World”: An Interview with Julia Hillman

By Junko Sakoi

Julia Hillman is the fourth/fifth grade English Language Development (ELD) teacher at Blenman Elementary School in the Tucson Unified School District (TUSD) located in Tucson, Arizona. As a multicultural curriculum coordinator, I observed her teach in the classroom and became interested in her use of multicultural literature with students. Students in this classroom are predominantly from working class families and are first-generation immigrants and refugees from Mexico, Central American, the Middle East, Southeast Asian, Africa, and the Pacific Islands. Many of these students are English Language Learners (ELLs). Julia has worked hard to integrate multicultural and international children’s literature within the curricular framework for a curriculum that is intercultural (Short, 2009).

Julia works to create a classroom where students feel valued, respected, and embraced by displaying literature that reflects students’ cultures and experiences. She also implements response strategies such as cultural x-rays that show students’ cultural identities and displays world maps documenting each student’s home country and language. I became interested in Julia’s experiences and perspectives on multicultural literature, so interviewed her. She reflected on her teaching and shared her beliefs, insights, and teaching journey with the literature. The conversation has been edited for publication.

Why Multicultural Literature?

Julia shared her beliefs about multicultural literature, its role in her classroom, and its importance in providing access to diverse representations of people, culture, and language.

Julia: My purposes for using multicultural and international books are to offer students access to the world and its people, including examples that show empowering portrayals of their cultures. Also, students who belong to groups that have been marginalized should be included, encouraged to pursue their education, and develop their talents. How encouraged would you be if (as a student) you only saw yourself portrayed as a villain, or slave and never as a hero, scientist, or doctor? How encouraged would you be if the stories you read about your culture were inaccurate, demeaning and degrading, or if your culture was invisible within the school’s curriculum? Would you feel dis-identified with school or as part of the school culture? When groups that have been marginalized continue to be excluded from the curriculum, what does that say about us, as educators, and what messages does that send to our students? Those are some of my reasons for using multicultural literature.

Through literature, students have become familiar with multicultural and international characters, and have connected to them, their stories, experiences, and lives. This is important to me and to students. I want to promote familiarity across cultures, and encourage respect across cultures both within my classroom and generally speaking. The message I would like to send is one that has transformed the way I see the world. There are many ways of living in the world; my way is normal to me, but it is not the norm when you consider the world’s diverse population. This approach helps me feel connected to all people, and inspires empathy, compassion and understanding for different ways of life. This understanding has made teaching more interesting and meaningful. There are times I feel like teaching is too difficult for too little pay, but when I reflect on my purposes in education I find comfort in knowing that I’m making changes in my classroom by including and welcoming the world and its people both in my classroom which is very culturally diverse, and through literature.

Critical Inquiry through Multicultural Literature

I asked Julia about her current teaching practice using multicultural literature.

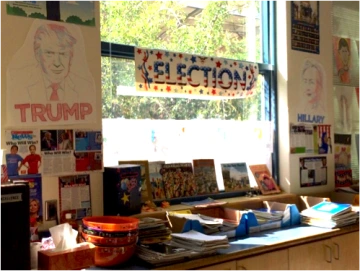

Julia: I use multicultural literature as part of thematic units across subjects and as part of literacy, specifically for silent reading, partner reading, literature circles, writing, math, homework and inquiry. What surprised me was the role that books played during our 2016 Election Unit. Many of my students had background knowledge from exploring multicultural literature on Civil and Human Rights, heroes, art and artists, scientists, innovators, books about war and peace, and other multicultural and international books. Several books students referred to during our Election Unit were Rosa by Nikki Giovanni (2005), White Socks Only by Evelyn Coleman (1996), and The Story of Ruby Bridges by Robert Coles (1995).

During the Election Unit, students read Scholastic articles about the electoral college, the candidates, third parties, and more, and a chapter book, The Election Book: The People Pick a President (Jackson, 1992), a picturebook Grace for President (DiPucchio & Pham, 2008), a variety of newspapers, listened to the candidates’ speeches and debates, and discussed the election from their perspectives. Students were put off by Trump’s use of stereotypes when talking about Mexican immigrants, Mexican people, Muslims and his sexism toward women. Later, it occurred to me that students had the vocabulary to describe this behavior from their background with multicultural literature and the many discussions we had.

Post-election, students became disenchanted with the election process and results. This feeling was expressed the day after the election, when a student ran up to me and said, “I told you Trump was going to win! I told you Americans hate Muslims!” I asked, “Is it fair to say that for all of an entire group of people? Where have you heard stereotypes like the one you just offered me before?” She looked at me and said, “Okay, okay, not ALL but A LOT of people voted for Trump! I wasn’t surprised Ms. Hillman.” We discussed the popular vote versus the electoral vote, and how many people voted against Trump. The message I tried to send this student was that we have respect for religious freedom, such as Muslims, despite the election results.

Our plan that day was to watch Clinton’s concession speech and Trump’s acceptance speech. We got through the concession and had small group discussions. I observed a group of students crying as they discussed the election results. “At least I’ll have a few more weeks with my dad,” a student commented. Students created heart maps to express their feelings, we discussed them, and took a break.

Once we started listening to the acceptance speech, students began to groan. A student asked me to turn it off. Then several more yelled out, “Turn it off!” The first student to complain said he didn’t want to hear what Trump had to say. He continued, “He said Mexicans are rapists.” Students continued to add comments they had heard Trump say during speeches and debates. “He wants to BUILD A WALL!” they said. “He calls women fat and he is fat! He doesn’t think it’s okay for women to be fat but he thinks it’s ok for men to be fat.” “He keeps talking about Muslims and Mexicans. That makes people think we’re bad.” Students continued with comments like, “I can’t believe he won. Why did people vote for him? We don’t want to watch this. Can we do something else?” “Hillary is bad, too!” a student commented. “She deleted all of those emails. They are both bad. I voted for Bernie!” The same student asked, “What about heroes? Can we study people who have made things better, and how they did that? Can we study Civil Rights again?” Several students agreed so we discussed and voted on what to investigate next.

Now that I’m reflecting on the role of multicultural literature, it seems clear that the literature provided students with the background knowledge of various social issues and injustices. Students developed an understanding of the danger of hateful rhetoric. They developed a disdain for unfair policies and racism to the point of disgust with the election results.

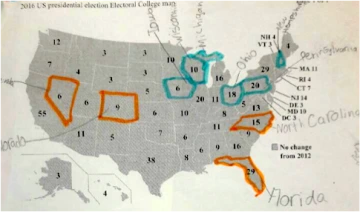

After we investigated the theme of Movements (see Figure 1) for several weeks after the election, students became empowered to participate in the Election Unit once again. I asked, “What questions do you have now?” “How did Trump win?” was a common question, so, as a group, we reflected on the election by identifying battleground states and reviewing the promises Trump made to the people of those states. After investigation, we revisited the question- “Why do you think these states voted for Trump?” “He promised these people jobs,” students answered. “Some people who lost their jobs were blaming immigrants and they liked how Trump blamed immigrants,” a student commented. They began to see Trump’s win as a result of a confluence of factors including promises he made to battleground states, people not voting, misinformation about the candidates, and the DNC rigging the primaries.

I had the opportunity to observe in Julia’s classroom during this 2016 election unit. Her students were immersed in the unit and had heated discussions. They showed tensions and confusion, and they explored the election and the social structures, norms, misconceptions, and stereotypes from critical and open-minded perspectives that impacted their understandings of the election cycle. Their strong background knowledge and broad understanding of social issues led them to in-depth inquiries based on their explorations of multicultural literature and various other resources such as newspapers, magazines, and films before and during the election unit. I observed that Julia always encourages her students to engage in critical inquiry about the social and cultural issues portrayed in stories by making connections to the students’ own lives, asking questions like what the story is for, who writes the story, what messages are portrayed in the story, and whose voices are not heard in the story.

Suggestions for Multicultural Literature Integration in the Classroom

Finally, I asked Julia for instructional advice. Here are Julia’s suggestions about how to integrate multicultural literature into the classroom:

Julia: Students explore multicultural and international books of interest to them, engage in critical discussions and action, and respond to the texts in various ways. Sometimes, they read several picturebooks a day, aside from Avenues stories (the basal reader), such as If the Shoe Fits (Soto & Widener, 2002) and Honoring Our Ancestors: Stories and Pictures by Fourteen Artists (Rohmer, 2013). Some students read multicultural chapter books, too. During art, I pass around a collection of multicultural and international literature about art and artists that include drawing books, music books and poetry. Students can investigate the books and draw, paint or create something of interest to them, or in connection to the unit we are investigating.

From my view, best practice means that the books are integrated, and students have access to multicultural literature for silent reading, homework assignments, and across subjects. Students should both have access to books written about diverse scientists, mathematicians, writers, artists, and historical figures and should also have books written by diverse authors. Having a wide range of books offers students opportunities to inquire about the world and its people, world events, and areas of interest to them. Here are some simple ways I have found to integrate multicultural literature:

- Display multicultural literature around the classroom so that students can begin observing and exploring.

- Allow students time to browse the literature before recess, lunch or dismissal every day or several times per week.

- Read one or two books aloud per day. Students can discuss the stories in small groups and record any questions they have.

- Include student read-alouds across subjects, such as famous artists, scientists, and mathematicians.

- Include small group student read-aloud and discussions.

- Offer students 20 minutes per day or twice a week to partner read, discuss and engage with the literature.

- Choose a day for students to read the literature with partners or in small groups, then discuss and present their connections to the class.

- Have students choose a multicultural chapter book from a list of books from the Worlds of Words (wowlit.org) website. Students can read the book for homework and respond in a format of their choice.

- Students can choose a multicultural book to read aloud before dismissal.

Final Thoughts

Students come into the classroom with their identities, abilities, and experiences. Julia has learned about her students: who they are, what their backgrounds are, and the value they place on their home languages and cultures. Using this knowledge, she encourages them to challenge injustice and stereotypes and value diversity. Together with students, she has thought through the integration of inquiries, response strategies, and engagements using multicultural literature and various forms of texts such as newspapers, magazines, and media.

Since the 2016 election unit, her students, who are mostly immigrants and refugees, have expressed tensions, confusion, and concern about their lives and their families’ lives. An Afghan student expressed in her writing, “I don’t belong here.” Like her, many of these students feel treated as if they are “others” in this society. Julia’s story demonstrates how significant it is to bring literature and students together, thus giving them time to reflect on themselves and foster a sense of inclusion as members of society, thus providing insight into the world beyond their homes.

Our classroom doors need to display “a great big ‘welcome’ sign” for all students in our schools, communities, and society (Sung & O’Herron, 2016). As Julia found, multicultural literature is a powerful resource for promoting this kind of welcome.

References

Short, K. (2009). Critically reading the world and the world: Building intercultural understanding through literature. Bookbird 47(2), 1-10.

Sung, Y. K., & O’Herron G. (2016). Sliding glass doors that open South Korea for American children. In. K. Short, D. Day, & J. Schroeder (Eds.), Teaching globally: Reading the world through literature (pp.137-160). Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Children’s Literature Cited

Coles, R. (1995). The story of Ruby Bridges. New York: Scholastic.

Coleman, E. (1996). White socks only. Morton Grove, IL: Albert Whitman.

DiPucchio, K. (2008). Grace for president. New York: Scholastic.

Giovanni, N. (2005). Rosa. New York: Henry Holt.

Jackson, C. (1992). The election book: The people pick a president. New York: Scholastic.

Rohmer, H. (2013). Honoring our ancestors: Stories and pictures by fourteen artists. San Francisco, CA: Children’s Book Press.

Soto, G., & Widener, T. (2002). If the shoe fits. New York: Puffin Books.

Junko Sakoi is a teacher trainer and program coordinator in the Multicultural Curriculum Department in Tucson Unified School District, Tucson, Arizona.

WOW Stories, Volume V, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/v5-i2.