Learning through Engagements with Multicultural and Global Literature

By María del Rocío Herron and Julia López-Robertson

Rocío is a PreK teacher at Jackson Creek Elementary School in Columbia, South Carolina and Julia is a teacher educator at the University of South Carolina. Our meeting was destined; I (Julia) happened to be in my office one day in the summer of 2008 when Rocío entered our departmental office with questions about teacher credentialing and certification. Since I was the only faculty member around that day, our administrative assistant sent Rocío my way. Coincidentally, a few days prior I had spoken with the principal at my youngest son's school and she shared how unsuccessful she had been in finding a Spanish teacher for the preschool. It was fate; here in my office was a bilingual Spanish-speaking teacher searching for a position! Our paths were meant to cross. I immediately called the principal and my son's school and made an appointment for her to meet with Rocío and the rest, as they say, is history. Rocío spent a few years as the Spanish teacher and teaching assistant at the Montessori program and eventually became a certified teacher with her own classroom.

Fast forward a few years; in the fall of 2017, a brand-new school, Jackson Creek Elementary , opened with the principal from the Montessori program at the helm. Rocío moved to this new school as a Pre-K teacher and I joined her. I have taught literacy methods on site for many years and worked closely with my son's former teacher. I had not, however, worked with a bilingual teacher and was very excited for the chance to work with Rocío. In what follows we share some of our experiences using multicultural children's literature with young Pre-Kindergarten children. The first vignette is told in Rocío’s voice, where she describes how she "brought books to life" through an inquiry into students' cultural heritage using global children's literature and cooking demonstrations. The next vignette describes my work as a teacher educator and how my position working with early childhood educators played out in Rocío's classroom through a favorite children's book.

Bringing Books to Life-Rocío

Many years ago, I asked myself, "How can I bring books to life for my students?" Online I found quite a bit of information and ideas for activities, such as storytelling baskets, dressing up, baking, acting out the story, creating a storybook, creating alternative endings, and story-themed crafts. Although I appreciated these ideas, they did not meet my needs and did not help me connect with the diversity of the students in my classroom; specifically, their ethnic, regional, religious, and linguistic diversity. I wanted these preschoolers to acknowledge, be conscious of, and value the differences in their personal or family cultures so that one day they see their culture as a tool to navigate and understand the world, instead of a barrier as it was sometimes presented.

I started looking for books that reflected students' personal experiences and connected family and school experiences as a part of a family unit. I started the family unit with the children by provoking conversations about people around the world through the video The World's Family (an embracing culture story). After viewing the video students were curious to look for the countries mentioned on the world globe, and the conversations started. Students asked so many questions about the video, such as, "Where is the big clock?" They also made statements such as, "I want to know about that building that is slanted," and "My dad went to Japan for work, and I want to learn about what he saw." To further explore what students wanted to learn, I gathered books from the public library and brought them into the classroom. I wanted students to become familiar with the names of different countries around the world. Browsing and reading books in the text set, students were able to see real pictures and discover, or point out, differences in the food, clothes, and languages across countries.

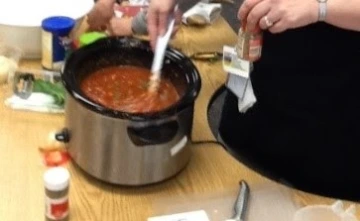

After a week of investigation, I decorated a voting box with red, white, and blue paper and made a slot in the top. We talked about the books and different countries, made a list, and voted on one country they would like to investigate further. The winning country was Italy. We happened to have two teachers in our school whose families were from Italy. I talked with the teachers about coming to the class and discussing Italy with the children. In preparation for their visit, we read the book Pizza for the Queen (Castaldo & Potter, 2005). Our guests talked about Italy and the food they like to make and eat and invited the children to cook with them. Together we made spaghetti and meatballs; Figures 1 and 2 show the cooking process. The children were involved in real cooking; they measured, stirred, poured, and of course, ate!

Investigating the books in the text set provided students with examples of the different foods and places where people live and helped them gain a little understanding that people are different and also share similarities. While cooking and later eating the meatballs, one student said, "my mom makes these but in soup." Working on this inquiry together was a great model for what was to come next.

My goal was to have each family engage in a study of their cultural heritage. I sent a letter to parents explaining the cultural heritage project and included a questionnaire asking about their family's cultural heritage. I asked them to take a moment to complete the survey along with their child and use that opportunity to teach their child information about their family's cultural heritage. Parents were then asked to help their child decide on four symbols that represent their culture (food, clothing, sports, music, etc.), and draw or find images for those symbols. Each child came to school with the questionnaire and symbols, and shared them with the class. We put the finishing touches on the family projects (see Figure 3) and invited the families for a culminating celebration of our collective Culture Story (see Figure 4).

Introducing multicultural and global literature in our classroom, we discovered that students were more involved and more open to speaking in their native language. Also, other students showed interest in and frequently tried to speak in their friend's native language. The stories we read helped students' imaginations and also helped them connect their personal experiences with those in the books.

Connections with Preservice Early Childhood Teachers & Cuentos-Julia

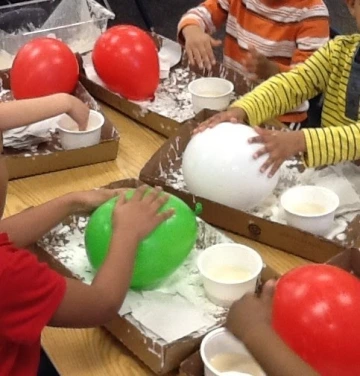

As noted, I teach an undergraduate literacy methods course at Jackson Creek Elementary and work with Rocío and her students every week. A major component of our course is the time we spend with the Pre-K children in a program I call Amiguitos--a Spanish word of endearment for 'friends'. Preservice teachers create lessons based on multicultural children's literature and implement them weekly with their Amiguitos. As preservice teachers, students learn about the importance of incorporating quality multicultural children's literature in all classrooms regardless of the backgrounds of the students (Freeman & Freeman, 2004). Creating weekly lessons, teaching those lessons, and reflecting on the teaching provides students with the opportunity to receive immediate feedback and the necessary scaffolding to support their teaching. Additionally, preservice teachers are able to see firsthand the level of engagement children have when presented with books where they can see themselves reflected.

On Friday mornings I return to Rocío's class and engage the children with bilingual stories/cuentos. For about one and half hours I read aloud a variety of children's books, listen as the children share stories with me as they make connections to the books, and sing children's Spanish songs and fingerplays. Each Friday, I read two books and end with Niño Wrestles the World by Yuyi Morales. The book tells the story of Niño, a young boy who uses his imagination to wrestle a bunch of bad guys and save the world. This book is beloved by each and every child in the class. Since they are so familiar with the book, it has turned into a theatrical shared reading; we groan, laugh, and join Niño as he wrestles the bad guys. Most Fridays, I basically start us off reading and then turn the pages as the children excitedly read aloud with me. I was not a fan of the book when I first saw it; I am not a fan of lucha libre, but after my first engagement with children and the book, I was sold!

Closing Thoughts

While only a few children in the class are bilingual (speaking both Spanish and English), every child in the class believes that they are bilingual and makes sure everyone entering the class knows this. As Rocío noted, reading bilingual and multicultural books with children helps them learn about each other, try out an unfamiliar language, and fully engage with stories that they can connect to in some manner.

Children's literature plays a major role in Rocío's classroom. Children are engaged in the literature with her daily, preservice teachers create and engage them in weekly lessons focused on children's literature specific to their interests, and on Fridays I engage the children in bilingual songs and books. Inquiries into a text set about countries around the world and 'tasting' a cultural dish began the journey into understanding different cultures while the family unit brought the inquiry to the individual family. Authentic engagements with quality bilingual children's literature and multicultural and global literature have opened the children's worlds from the local to the global in culture, language, and ways of being.

One feature of our work together that cannot be overemphasized is the power of collaboration. Rocío and I met by circumstance and developed a professional relationship that supports us both in the critical work of locating quality multicultural and global texts for young learners and preservice teachers at the university and creating engagements that develop cultural awareness in our students through literature and interactions in Rocío's preschool bilingual classroom.

References

Freeman, Y. & Freeman, D. (2004). Connecting students to culturally relevant texts. Talking Points, 15(2), 7-11.

López-Robertson, J. (2013). Tammy and the Sensations: Assessing through talking about stories-A preschool approach. In D. Stephens (Ed.), Reading assessment: Artful teachers, successful students (pp. 31-41). National Council of Teachers of English.

Children's Literature Cited

Castaldo, N. F. (2005). Pizza for the Queen. Illu, M. Potter. Holiday House.

Morales, Y. (2015). Niño wrestles the world. Square Fish.

María del Rocío Herron teaches PreK at Jackson Creek Elementary School in Columbia, South Carolina.

Julia López-Robertson is a Professor in the Department of Instruction and Teacher Education at the University of South Carolina.

© 2020 by María del Rocío Herron and Julia López-Robertson

WOW Stories, Volume VII, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work by María del Rocío Herron and Julia López-Robertson at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/volume-vii-issue-1/5.

WOW Stories: Connections From The Classroom

ISSN 2577-0551