Creating a Window to the World

by Jennifer Crosthwaite and Tiffany Altman

The speaking child has the ability to direct his attention in a dynamic way. He can view changes in his immediate situation from the point of view of past activities, and he can act in the present from the viewpoint of the future. (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 36)

At the beginning of our literary journey, our team decided it was critical to create a strong foundation for student dialogue. In an era of high stakes testing and an overwhelming focus on teaching specific skills in order to meet the necessary standards, educators have become the masters of information while the students have become the passive recipients of our knowledge. As a result, student-centered learning is often pushed to the side in order to make room for drilling of skills. Educators tend to forget and not pay heed to the importance of encouraging students to take ownership of their learning through dialogue.

An important part of empowerment is allowing students to embrace their thoughts, responses, and opinions and building such knowledge through peer-to-peer interaction and dialogue. As Vygotsky states, student speech and dialogue is the foundation of student learning, connecting their past, current, and future knowledge. Undoubtedly, children are able to change their perspective on situations depending on their past experiences, while also taking into account future possibilities. Dialogue allows this shift to occur in a way that supports the dynamic nature of reflection, thought processes, and development of perception. The following activities allowed students to embrace their experiences and bring literary dialogue to the forefront of their education through picture books and read alouds as a steppingstone to global connections.

The Cunningham Colts, a community in Henderson, Nevada, was built on the passion, dedication, and drive of five third-grade teachers. We embarked on a journey in the 2012-2013 school year to bring world literature to students. As a grade level, we had already been working cooperatively together the past few years. We valued the importance of supplementing our required reading series with exceptional literature that connected with math, science, and social studies to provide our students with a richer foundation about the community and world they live in.

As a grade level, we met formally and informally. We sat together daily during our lunch hour, which provided an opportunity to share stories we had read, activities we had done, and student reactions. During these short yet productive sessions, we discussed our initial hesitations of sharing stories that touched on sensitive issues such as poverty, hunger, and other global issues. These hesitations mostly stemmed from our fear of how our students might react and the questions they might ask. Through conversation, practice, and support of each other’s goals, we came to realize that the dialogue that would emerge and questions that would be asked from sharing these stories were the foundation for helping students understand their important role in the world and the changes they can make to make the world a better place.

Our formal meetings provided opportunities to discuss the book we had chosen, For a Better World: Reading and Writing for Social Action (Bomer and Bomer, 2001). Such meetings allowed us to make connections and provide classroom examples of what we had done in our classrooms and how these experiences connected to this text. Finally, these formal meetings provided an opportunity to plan and eventually reflect on our classroom experiences–an essential aspect of our practice.

Student Guided Questions as a Basis for Inquiry

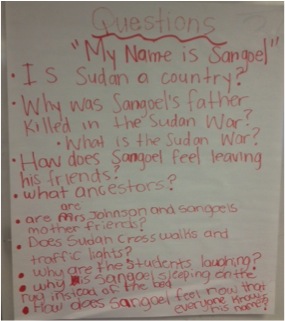

Children are naturally curious, inquisitive, and bubbling with questions. With every read aloud, dozens of questions emerged in our classrooms. With every turn of a page, children’s hands rose in an excitement of wonder. With every illustration observed, students curiously leaned forward to talk about all aspects of the pictures including character’s facial expressions, actions, and feelings evoked as readers. As educators, we constantly nurtured and celebrated their excitement and curiosity and often contributed our own questions and wonderings. Throughout the school year, we recorded our questions in large poster paper and showcased them around our classroom. Students often referenced these questions during their journal responses and served as a means for deeper and more reflective responses.

The process of asking questions was also an important part of our classroom environments. In fact, the act of reading is a social process; it is a phenomenon that not only occurs to an individual, but can also exist within a greater context that includes interpersonal aspects of community learning. The types of opportunities given to students to engage in collaborative learning greatly affect their academic achievement. Eun (2010) states:

A collaborative culture would value common learning goals that are shared by the students as each contributes to the overall classroom learning. Competition would be devalued as the achievement of the shared learning goal would serve as a common purpose toward which everyone strives. (p. 408)

Throughout our classrooms, a sense of camaraderie and support was exemplified as students agreed and nodded when others asked a question. For example, while reading My Name is Sangoel (Williams, 2009), Michael, “Is Sudan a country?” Immediately, this comment created a domino effect of other questions. As students agreed, supported, and encouraged each other through their dialogue, questions were recorded on chart paper, as seen in the following figure.

• Is Sudan a country?

• Why was Sangoel’s father killed in the Sudan war? What is the Sudan war?

• How does Sangoel feel leaving his friends?

• What are ancestors?

• Are Mrs. Johnson and Sangoel’s mother friends?

• Does Sudan crosswalks and traffic lights?

• Why are the students laughing?

• Why is Sangoel sleeping on the rug instead of the bed?

• How does Sangoel feel now that everyone knows his name?

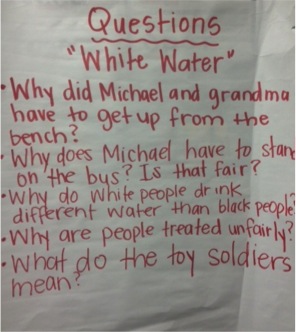

Another book, White Water (2011) by Michael Bandy, is a true story about the experiences of the author who lived during the time of the Civil Rights Movement. Bandy discusses how he fantasized about tasting water from the “Whites Only” water foundation because it seemed more refreshing, cool, and tasty. At the end of the story, he learns that both water fountains receive water from the same pipe and that many of the challenges in his life were merely part of his imagination and so could be overcome.  The following questions were generated by students during the read aloud:

The following questions were generated by students during the read aloud:

“White Water”

• Why did Michael and grandma have to get up from the bench?

• Who does Michael have to stand on the bus? Is this fair?

• Why do white people drink different water than black people?

• Why are people treated unfairly?

• What do the toy soldiers mean?

Literary Letters as Written Dialogue

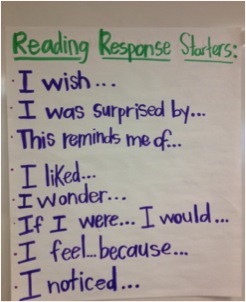

Literary letters were used throughout the year as a way to engage students in written dialogue with their peers in a formal, yet non-threatening way. In the beginning of the school year, we recognized that students often do not know how to talk about a book. They are constantly concerned with making sure they answer a question about a text. In other words, students are accustomed to reading a text and answering literal-level questions. The purpose of literary letters is to go beyond this thinking and more importantly, beyond I liked this book. As a means to help support students, we posted anchor charts of Response Starters. Response Starters were also an important resource for ELL students, as well as those students in special education, since it allowed them an opportunity to have a specific reference point for their thoughts. Students were often observed looking up at this chart and sometimes getting out of their seats to better see the chart paper. Giving students a safer form of responding by providing ideas to generate their thinking, as well as reminding them that they had the freedom to create their own response starters was a successful way of improving student participation and metacognition during the writing process. The following is one of the anchor charts posted in the room throughout the year:

• I wish…

• I was surprised by…

• This reminds me of…

• I liked…

• I wonder…

• If I were…I would…

• I feel… because…

• I noticed…

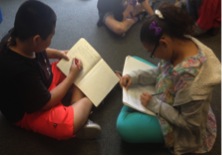

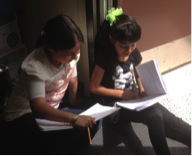

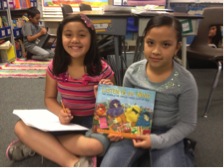

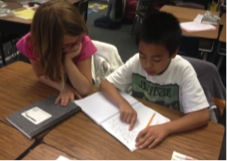

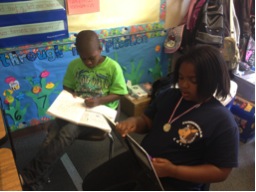

After each read aloud, students were asked to respond in their journals. Students then partnered with another peer (usually predetermined by the teacher) to read aloud their response. Once they read their responses, students were asked to switch journals with each other and begin their literary letter. Finally, students read their letter to their peer and returned the journal. The following pictures were taken during these exchanges:

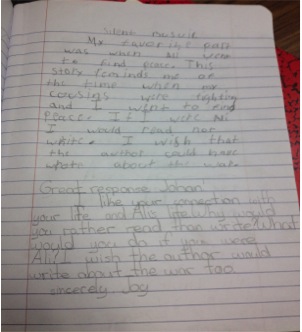

The following is an example of a literary letter from a book called Silent Music: A Story of Baghdad by James Rumford (2008) about a young boy living during times of war who finds peace by writing in caligraphy.

“My favorite part was when Ali went to find peace. This story reminds me of the time when my cousins were fighting an I went to find peace. If I were Ali I would read not write. I wish that the author could have wrote about the war”

“Great response Johan! I like your connection with your life and Ali’s life. Why would you rather read than write? What would you do if you were Ali? I wish the author would write about the war too. Sincerely, Joy”

This letter, along with the others created throughout the year, showed that students were able to make connections with characters and understand the experiences of others. Literary letters was an activity that all students enjoyed because they were able to share their thoughts about a book, while also learning how their peers responded to the same story.

You’ve Got Mail: Perspective Postcards

Another engagement that we decided to do was to write postcards using the characters of the books we read. We found that it was important to teach students about point of view and perspective. By doing so, students developed a sense of empathy towards others. The ability to experience the unknown or unfamiliar through literature widens our understanding of the world, particularly important when the unfamiliar pertains to opposing and divergent views. Acquiring an empathetic perspective towards the distant and unfamiliar allows students to better cope with our increasingly diverse and interconnected world. In a globalized world, students should begin to value those who may be different, which will encourage them to become mindful and develop kindness, positive cooperation, and appreciation of all. Students created postcards using the point of view of a character they chose. They were also given the choice to write to another character from the same story or a character from a different story, since many of the books we read had similar themes.

This postcard was written from the point of view of the character Zero from Zero (Otoshi, 2010), who always felt like he was not worth as much as the other numbers.  He eventually realizes, through the help of supportive friends, that he can be worth a great value when joined with other numbers. This book illustrates the importance of cooperation, being yourself, and respecting others.

He eventually realizes, through the help of supportive friends, that he can be worth a great value when joined with other numbers. This book illustrates the importance of cooperation, being yourself, and respecting others.

“Dear Zero, I know why are sad. You are sad because you are the least number. By the way you can still be a big number with 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7. I know you are sad, but remember you are the first number! Sincerely, Blue”

The next postcard was written from the perspective of Ali, the main character from Silent Music. Ali writes to his mother about his fears of living during times of chaos and war.

The next postcard was written from the perspective of Ali, the main character from Silent Music. Ali writes to his mother about his fears of living during times of chaos and war.

“Dear Mom, I hate when bombs and missiles fall down. I hate when there is a war. Can I ask you a question? Are bombs and missiles going to fall from the sky? I was so scared when bombs and missiles were falling from the sky. Love, Ali”

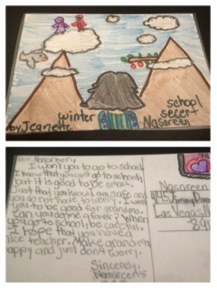

This next postcard was written from the perspective of Nasareen’s mom, who was taken by the government in Afghanistan and leaves her daughter with her grandmother.  In this postcard, Nasareen’s mom advises her to continue to work hard and study.

In this postcard, Nasareen’s mom advises her to continue to work hard and study.

“Dear Nasareen, I was you to go to school. I know that you cant go to school, but it is good to be smart. Just that you know I am safe and you do not have to worry. I want you to be good for grandma. Can you do me a favor? When you go to school, be careful. I hope that you have a nice teacher. Make grandma happy and just don’t worry. Sincerely, Nasareen’s Mom”

Understanding Human Rights

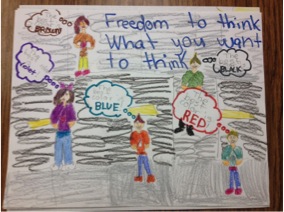

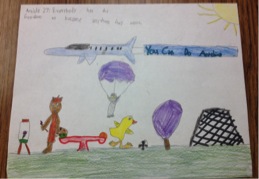

An important theme throughout the year was teaching about human rights. We read We Are All Born Free by Amnesty International (2011). This book was read in the beginning of the school year to help student connect this text with others that would be read throughout the year. As the school year went on, students were able to make clear connections and refer back to human rights. We encouraged students interpret these rights by asking them to choose one right and make an illustration of what it means to them. The following are two student examples:

“Freedom to think what you want to think” “The best color is brown,” “The best color is violet,” The best color is blue,” “The best color is red,” and “The best color is black.”

“Article 27: Everybody has the freedom to become anything they want. You can do anything”

“Article 27: Everybody has the freedom to become anything they want. You can do anything”

Environmental Awareness

One particularly important unit was environmental awareness. Bomer and Bomer (2001) state, “The teacher’s role is to help children hone one topic, delve into it more deeply, perhaps sustaining discussion over several days and feeding it with written responses and rereading” (pp. 49-50). We began with student-generated questions and ideas about recycling and taking care of our earth. This led us to read several books about the earth, compost, recycling, renewable energy, and many nonfiction texts about the earth’s composition. It was an engaging way to connect literature, science, and social studies. One book in particular sparked amazing curiosity among students, Energy Island; How One Community Harnessed the Wind and Changed their World by Allan Drummond (2011). This story tells about a small Danish island decided to become energy independent by using renewable resources to reduce carbon emissions and so has both a narrative and informational components. It led students to engage in inquiry about whether or not our country and state use renewable resources, and the effects of using them for our planet. We believe that these are the type of stories that genuinely engage our students, create a love for learning, and most importantly, can change the world.

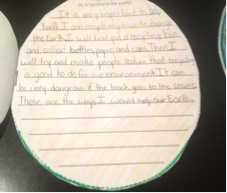

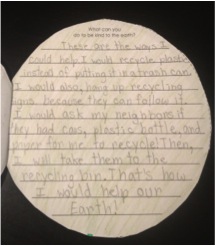

The following are a few pictures from activities during our unit.

“It is very important to help Earth. I can recycle my trash to change the Earth. I will first put a recycling bin and collect bottles, paper, and cans. Then I will try and make people realize that recycling is good to do for the environment. It can be very dangerous if the trash goes to the sewer. These are the ways I would help our Earth. “

“These are the way I could help. I could recycle plastic instead of putting it in a trashcan. I would also, hang up recycling signs because they can follow it. I would ask my neighbors if they had cans, plastic bottles, and paper for me to recycle! Then, I will take them to the recycling bin. That’s how I would help our Earth!”

World Literacy: Making a Difference

Our culminating project brought together the reasons we read world literature–learning about the experiences of others, widening our perspectives of the world, and building empathy and care for those who differ from our own cultures. Our students decided to write, illustrate, and publish books to donate to a third world country in hopes of improving education and world literacy. Throughout the year, we constantly referred to The Librarian of Basra: A True Story from Irag by Jeanette Winter (2005), Nasreen’s Secret School by Jeanette Winter (2009), and We are all Born Free (2011) by Amnesty International (2011). These books instilled a strong sense of what the world is like for children and education.

Upon reading these texts and referring to the article of human rights concerning education for all individuals, one student asked the important question, what can we do to help? It was as though all of our read alouds, dialogue, questioning, and wonder had come together to bring about this important question about advocacy, change, and agency. Although we had already thought about having students write books to donate, they initiated the idea, giving them authentic ownership over this endeavor. After our discussion and brainstorming ideas, we decided to use our own literacy and knowledge to publish books for other children. Through a long process and many revisions, we were able to donate over 80 children’s books published by our very own authors and world advocates. Books, along with school supplies that we collected, were donated to an organization called Teach Cambodia for a school being built in the small village of Boeng.

As in other units, this activity led students to learn more about Cambodia, other world problems such as hunger and malnutrition, and ways to combat such problems. As world advocates, our students learned about peanut butter as a new and effective way of helping those who are malnourished in other countries (Project Peanut Butter), leading them to also engage in a peanut butter drive to send to Cambodia along with the books and school supplies. Undoubtedly, our students became change agents and world advocates. Through engaging in world literature, we made a difference in the world. A true education is making a difference for ourselves and the world we live in.

The following are pictures from our book showcase event:

Children’s Book References

Amnesty International. (2011). We are all born free: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. London: Frances Lincoln.

Bandy, M.S. (2011). White water. Somerville, MA: Candlewick.

Drummond, A. (2011). Energy Island: How one community harnessed the wind and changed their world. Toronto, Canada: D&M Publishers.

Mortenson, G., & Roth, S. (2009). Listen to the wind: The story of Dr. Greg & three cups of tea. New York: Penguin.

Otoshi, K. (2008). One. Los Angeles, CA: KO Kid’s Books

Rumford, J. (2008). Silent music: A story of Baghdad. New York: Roaring Book Press.

Williams, K.L. (2009). My name is Sangoel. New York: Eerdman.

Winter, J. (2005). The Librarian of Basra: A true story from Iraq. New York: HMH

Winter, J. (2009). Nasreen’s Secret School: A true story from Afghanistan. San Diego, CA: Beach Lane.

References

Bomer, R. & Bomer, K. (2001). For a better world: Reading and writing for social action. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Eun, B. (2010). From learning to development: a sociocultural approach to instruction. Cambridge Journal of Education (40) 4, 401-418.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Jennifer Crosthwaite is a teacher for the Clark County School District in Las Vegas, Nevada and is pursuing a doctoral degree in literacy at the University of Nevada Las Vegas. Jennifer is committed to social justice education and integrating world literature across the curriculum.

Tiffany Altman is a lead teacher at Rocketship Brilliant Minds Academy. Tiffany is the third grade English Language Arts teacher at her school and is passionate about instilling core values among her students, focusing on respect, responsibility, persistence, empathy, and initiative.

WOW Stories, Volume IV, Issue 8 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/iv8.

The journey with Genny and her students has been one of the most powerful experience I ever had with books about Korea. Childhood connections became a powerful tool for children to wake up their curiosity to Korean culture and kids in Korea. Eventually this whole experience let them to think about critical stance of reading. Even though language was not all in English, childhood connection helped them to jump over the huddle in language barrier yet helped them to study carefully other visual cues like illustrations in the Korean picture books in return. This particular story Genny O’Herron wrote is empowering for me as a member of ACLIP indeed.

I can honestly say that I truly enjoyed reading this article. When I search for information on reading within the classroom, the majority of the articles are based around the elementary and middle school aged students. I really appreciate this in-depth discussion of how the teacher helped her students make connections and allowed them to follow the path that the book took them on. I teach at the ninth grade level in all co-teaching classes. My students are mostly not very inquisitive. I believe they have been taught all along to simply read and do the questions. We have lost a lot of the fun in teaching reading and learning about the information in the book. I a very inspired by this classroom and the functionality of the processing of the actual information within the text. We need to teach our students how make those connection and inquire into why things are the way they are. I have always loved to read and have never understand the disdain that many students have for reading. However, I know that if I can get them even slightly interested in the subject matter at hand, then the process is so much smoother. Once again, this was a fantastic article that I will be passing along to my colleagues.

Thanks, I agree that there are few examples of using global literature in secondary school classrooms and there is so much potential at that age level. May kids, however, have learned not to think in schools because not much has been asked of them beyond basic literal level thinking. So while they are capable of so much thinking, they also have a long instructional history of not thinking which we have to get beyond. The potential is there, though, as you point out.