Supporting Personal Inquiry within a Collaborative Experience

By Gloria Kauffman with Krish Boodhram, Armand Bronqueur, Bindoo Caullychurn, Kim Han, Elizabeth Caselton, Dini Lallah, and Laura Burgess

The children remove their shoes and quietly enter the classroom, smiling and chanting in unison, “Good morning, Miss Gloria.” Their class is one of eight classes from Years 3 to 6 (Grades 2 to 5 in the U.S.) that come to the literacy lab once a week for an hour. Our purpose is to engage in critical talk around picture books with an international focus. The school is situated in a small village against a mountain; the only International Baccalaureate Primary School on the island of Mauritius, off the east coast of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. The majority of the children are Mauritians coming from a range of cultural backgrounds that reflect the descendants of the island from India, Africa, China and France. I came to the school three years ago to work with curriculum and professional development. The literacy lab, as a form of professional development, is a personal inquiry for me as the staff developer, while the study group is professional development for teachers to pursue group and personal inquiries (Thomas, 2008).

In the literacy lab our focus is on using text sets as a way of opening up individual inquiry within a collaborative experience, so that each child and teacher finds his/her own passion within that shared classroom experience. Teachers in the school struggle with issues of how children can explore, as a whole class or as individuals, group and personal inquiries and create a collaborative community of learners. “Even though ours is an inquiry-based curriculum, inquiries are completely guided by teachers. Prior to starting a unit, teachers have already made up their minds about what they want children to inquire into. As a consequence, stock responses are encouraged and any deviations are frowned upon or children are steered right back on track,” comments Krish. Inquiry coming from children is a huge risk for Mauritian teachers who have only experienced instruction delivered as lecture and as memorization of “facts” deemed important by the government mandated test. As part of the school focus on a curriculum of inquiry, we are examining critical thinking and inquiry through literature, in particular by having children explore their personal connections and inquiries through text sets of conceptually related books organized around a broad theme. Taking this leap of faith and trusting children as learners within a curriculum that is not fully understood by many teachers is a huge risk for all of us.

Our Professional Learning Context

As staff developer, teaching and learning are rooted in belief so these processes need to be supported by teachers coming to understand the relationship between belief, theory, and practice (Short & Burke, 1991). We meet as teachers every Wednesday after school in a study group to discuss a range of topics. We have focused on improving our teaching practices, more specifically on how to push children’s thinking more deeply about issues that are important in their lives and the world. My past research working with children in literature discussions led me to share ideas about how we could introduce literature to children to develop critical thought.

Since my role in this school is to coordinate curriculum development and to help teachers improve their teaching practices, the study group and literacy lab as a professional development were an option open to all teachers. The literacy lab offers an opportunity for teachers to observe putting theory into practice with me leading each lesson created from our study group discussions. I coordinate the curriculum in the lab, teachers attend the sessions and take field notes, and then all of us share and discuss those observations in study group. “The literacy lab and the study group have brought to me the ‘thinking together’ part. Through observations in the lit lab, writing it up, discussing issues in study group, I’ve been able to reflect and take it back to my teaching and practice,” shares Dini.

The literacy lab allows us to enact our professional study with children and move from theory into practice. Teachers who come to the lab are in the study group and bring their classes to the lab one hour a week for lessons that grow directly out of the discussions in study group. Our initial focus was on how to help children identify and talk about issues in picture books grouped together to form a text set (Short & Harste with Burke, 1996), a set of conceptually related books around a theme, in this case, the multiple journeys we experience in our lives and the lessons learned from these journeys.

We planned the curricular experiences and engagements so that we could get to know the children in multiple ways. Our curricular goals for the first few sessions in the lab were to gather preliminary information on how students viewed the concept of journeys and themselves as learners and the ways in which they talked about these experiences with their peers. We created a series of engagements to inform us of children’s attitudes and learning experiences about journeys, and then their attitudes and learning experiences about making connections and sharing those connections with their peers. “On the whole I must say that the children’s responses were beyond my expectation as their answers were very deep and the different strategies used contributed to their understanding and at other times energized the sessions,” reflects Armand. Through the process of experiencing these planned engagements, we came to understand children’s thinking and the tensions of building trust and sharing with others.

The curricular engagements were planned so that each experience built off of the next, adding knowledge about the concept of journeys by making connections and coming to understand a process of how to share those experiences with others. Along with multiple experiences we had multiple strategies to support children in their understandings and growth as critical readers and thinkers.

We started this nine-week action research by discussing literature related to the theme of “Journey” and what it means to engage in literature discussions with children. The broad concept of Journey is open-ended and a means of encouraging connections to self and generating ideas. It is not meant to be a unit of study with certain concepts to master or answers to find. The broad concept provides a frame within which children can move toward inquiry, posing their own questions, and finding individual answers to those questions (Short, Schroeder, Laird, Kauffman, Ferguson, & Crawford, 1996).

As a teacher study group we brainstormed and webbed out journeys to come to an understanding of the depth and breadth of the concept and to realize that each of us would pose our own questions and could find our own answers, and that these would be different for each member of the group. We needed to experience this process ourselves because the teachers’ own school experiences as children and adults had been limited to lecture with no experiences of discussing ideas with their classmates or their professors. Dini states, “Being able to discuss ideas based on observation and practice is not something most of us would have an opportunity to do in the normal course of the day.”

“The struggle is we have to collaborate. It is not easy to find agreement when each one has his/her own perception of the topic,” states Bindoo. Teachers struggled with the idea that this broad concept would allow each individual to explore a wide range of interests and yet be linked together to focus our discussions and would enable us to plan curriculum that related to all teachers and students.

Planning Curriculum to Enact Our Beliefs

The first session with children started the same way as with the teacher study group, webbing “What are journeys?” All eight classes had the opportunity to talk and web out their ideas of journeys. Not surprisingly, children came up with similar ideas as teachers. Children brainstormed journeys as:

- Going to another place.

- A special day.

- Somewhere you’ve never gone before.

- Something beautiful, fun, or exciting.

- Maybe spending a day at a friend’s place or grandmother’s place.

- The time from sun to night.

- It could be about nature.

- Or a change, an idea.

- You walk, go by car or plane.

- Or have no destination.

- Journey might be travel, a book, your mind, something to remember.

- How you live, a visit, a holiday, a trip.

- A way for better living.

- It might be immigration, to discover, a job.

- Doing research.

- Having an adventure.

- It’s something new.

- An advantage.

To get us started with Journeys, I read aloud the picture book Miss Rumphius by Barbara Cooney (1985), the story of a woman with three goals in her life — to see foreign countries, to live by the sea when she retires, and to make the world more beautiful. The story covers her life from a young child to an elderly woman and shares her journeys throughout her life time. After the read aloud, children were asked to web out the journeys of the main character. “Gloria did not accept or reject their answers. Instead, she challenged their thinking and the children were responsive to this strategy. This helped me understand how to conduct an inquiry and I must admit that this attitude is quite hard for me, who cannot remain silent for long,” noted Armand.

The journeys the children identified for Miss Rumphius included: Family, Migration, Travel (visiting different countries), Her Jobs (the processes she used within these jobs, such as painting as an artist), Her Mission (to make the world more beautiful), Visiting Cities, Library Work (reading about different places), Thinking, Unforgettable Moments, Time, Pollination (wind/birds to carry the seeds) and the Growing of Plants.

Each child chose one journey from their class web and created a recording device to express one of Miss Rumphius’ journeys. Ryan chose to draw a sketch of Miss Rumphius’ house by the sea as an end to her traveling journey and a beginning of her new journey into retirement. He commented about our process, saying, “At the beginning of the session, it seemed easy. Gradually, it got harder. Listing down the journeys of the old lady when she was young was just the start. We had to think of something to do like story maps, time lines, sketches, graphs, or cartoons with no one in the class using the same recording device.”

Children used a range of recording devices, such as a graph to show the journey of love, a written conversation to show the journey of helping, a comparison chart of all the hot and cold places Miss Rumphius visited and lived, a treasure map of her walking, and a list of all the places she visited. Small groups of children drew their recording devices on the same large sheet of chart paper to create a graffiti board of Miss Rumphius’ journeys throughout her life.

Using the journey webs from the study group and each class of children, we read through and categorized the ideas into themes. Once we had organized the ideas into categories, we discussed the categories to come to a common understanding of each category. “As a result of experiencing this kind of process, my teaching practice with EAL has improved to include more meaningful engagements, so I can focus on more depth in children’s thinking and more inquiry-based learning,” shares Dini. Through our discussion we named each category as a theme.

- beginnings of journeys,

- multiple perspectives about journeys,

- overcoming obstacles and fears,

- remembering journeys,

- cultures meeting cultures,

- journeys as dreams and hopes.

Focusing on these broad themes we could then explore each theme through conceptually related books grouped as text sets, each containing a variety of picture books, multiple genres and cultures and varied reading levels.

Exploring Browsing and Text Sets

Reading aloud and discussing picture books as a whole class was a powerful strategy to create community within the classes, focus our study, create shared understandings, and prepare ourselves for literature discussions in small groups. “What was lacking is teachers having a repertoire of strategies to scaffold children thinking more profoundly about texts and to articulate their thought processes more succinctly,” reflects Krish. After each read aloud, we discussed the different types of journeys in that book. Our whole class discussions helped children be less confused or unsure about how to talk about books when they moved to small literature discussion groups. They had experienced talking together and were aware of the tensions created in groups, especially when not everyone participates or comes to the group ready to share ideas, personal connections or opinions. “To close the session Gloria gave an idea of what the next session would be about — our own lives. Then she sent the children back to class. This is a interesting strategy as it gives the children the opportunity to start thinking about the next step as well as it allows them to notice and make connections to what they will do next,” says Armand.

Each read aloud related to one of the themes and was a way to gain an understanding of each text set in the study of Journeys. Miss Rumphius introduced the concept of multiple journeys and became the touchstone book we returned to often in our discussions and at the end of the study. This book connected to all of our text sets as well as to each of our lives — Luke’s Way of Looking (Wheatley, 2001) emphasized the need for multiple perspectives, The Pink Refrigerator (Egan, 2007) made real the need to overcome obstacles and fear while Five Little Fiends (Dyer, 2002) shaped understandings of new beginnings and perspectives. “My struggle is to have more strategies in order to think of a year-long plan to build on children’s interests, using wider ranges of text and helping children internalize their strategies for more profound thinking,” states Krish. I chose books for the read alouds that helped build multiple concepts about journeys and so we added to the journey webs for each class after the read alouds.

Creating text sets takes time. To do so, one must locate 8-12 picture books on each theme and make sure each theme has a variety of genres to capture the interests of children as well as to meet their reading abilities. Each theme also needs books with multiple perspectives and cultural views, enabling readers to find connections to their own lives, have their preconceived ideas challenged, and come to a new understanding of the broader world.

Once the text sets were created, we wanted the children to browse them and make a choice as to which set they wanted to spend their time reading and discussing. I talked to each class about choices and reasons for deciding on a set to read and discuss. I emphasized that they should think about their connections to the books, the appeal of the writing and illustrations to them, whether they could talk about the ideas in the book, and their interest in the theme. I warned them that choices based on whether or not their best friends were in the group could lead to not wanting to read or discuss the books because of lacking a personal connection or interest in the books.

The children did not have much experience handling books or talking about books and so I knew I would have to teach them how to browse. “At school, books are chosen by the teacher and there is not a wide variety. The same books remain in the class for the entire semester,” states Bindoo. Students were used to reading to gather facts and writing those facts in copy books. In order for children to choose a text set and spend time reading and discussing books, I started the session with the question, “What is browsing?” Each class brainstormed their ideas:

Preiyanka: Is it searching?

Chloe: Looking into different books.

Shuaib: When you look for a book and you’re searching something to read aloud.

Kartik: Take a book and look through it to see if it’s what you’re looking for.

Keshinee: Exploring for books and…

Rishab: Analyzing facts? The main points?

Kreetish: You’re looking at the pictures. You might read a bit.

Each table had a set of text sets in a basket clearly marked with the name of the theme. In groups of four, children stood at a table and chose a book from the basket. They were asked to hold the book and read the title, the end pages, and the first page to get a sense of the author’s voice. I also suggested that they flip through the book to view the illustrations in order to predict the story. They were reminded to check the author’s and illustrator’s name to see if they had read this author or recognized the illustrator. Once they had browsed one book, I asked them to move to another book in the basket. After five minutes, the group of four moved onto another table and repeated the process of browsing that basket of books. Kids caught on right away but it was hard for some to stand and not sit at the tables to browse. I also had to teach them how to put books back into the baskets with spines facing the ceiling and without damaging the covers.

Once all of the theme baskets of text sets had been browsed, children had to make a choice of which text set to read and discuss. As children made their selections, they were asked to reflect on why they had chosen the set in a quick write. Once the groups were selected, children sat with their group and each read at least one book to share with the group at the next session.

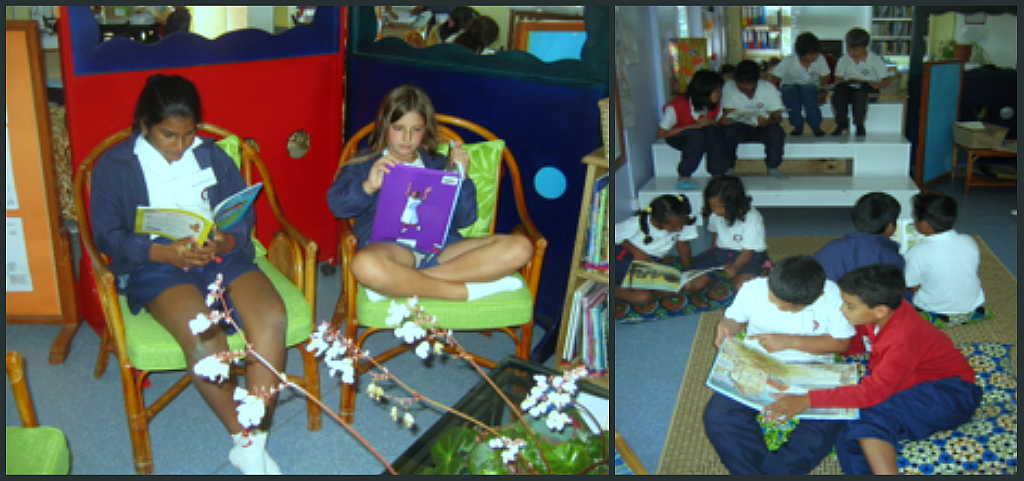

I encouraged children to read these picture books in multiple ways to encourage community building, thinking and conversation, I suggested they could read as partners or in groups of three, read and talk about what they were reading after a few pages, or read alone and then share. To build community and create a safe environment for sharing ideas, children were invited to move to different parts of the room to read on the risers, pillows or comfortable sitting areas. The most important aspect of getting ready for a discussion is being able to understand what is read and so it was important to support the range of reading abilities in each group.

Exploring Personal Inquiries with Text Sets

To understand how the groups functioned and supported individual inquiries, I want to share some of interactions from the text set group that was exploring Overcoming Obstacles and Fears as a form of journey. Some of the books in this text set included Scaredy Squirrel (Watts, 2006), Prince Cinders (Cole, 1997), The Other Side (Woodson, 2001), Teammates (Golenbrock, 1992), Oliver Button is a Sissy (de Paola, 1979), Summer Wheels (Bunting, 1996), The Name Jar (Choi, 1993), and The Ghost-Eye Tree (Martin, 1988).

The group of children looking at obstacles and fears each joined the group for different reasons. Keshinee had lost her father several weeks earlier and wanted to think about dealing with loss due to death. Cardine felt she did not have any fears and so wanted to understand people who did have fears. Andy was struggling through understanding divorce, Michelle was interested in issues of prejudice and racism, and Zain was dealing with being afraid to take risks.

These five children read and discussed the books, having heated discussions and supporting each other in exploring their individual issues. For example, after Zain shared Scaredy Squirrel (Watt, 2006) with his group, they suggested that he try to go places he had never been and venture out alone without his family, such as walking along the beach alone or going for a hike in the forest. Zain was open to the discussion and said he would try the suggestions. The group then moved on to helping Zain create a survival pack for his risk-taking adventures patterned after Scaredy Squirrel’s survival pack.

Michelle, who had moved from Ireland to Mauritius, opened up discussions about racism by confronting Cardine, whose mother is Indian and father is German, about Cardine’s treatment towards her when they were five-year-olds. She told Cardine she felt she had been excluded from play groups and made fun of because she had white skin, freckles and red hair while all the other children had brown skin, black hair and brown eyes. Cardine said that she had read books about how white people didn’t like people with brown skin and so assumed that Michelle would be prejudiced towards her. She shared how she believed what she had read. Zain asked her how she could believe what is written in books. The group teased Cardine, saying, “Well, she believes in Cinderella.” Cardine stated that they had been all taught to believe everything they read in school. The discussion was open and healthy with Cardine asking if anyone thought she still showed signs of being prejudiced. Cardine apologized to Michelle and asked her if she may have also been prejudiced because of her skin color, but Michelle said her best friend was a boy from Africa so color was not an issue for her. Andy, an American, talked about the reality that he still saw prejudice in the classroom toward anyone who didn’t speak French or Creole, the common languages of the island. This discussion led the group to decide to look into whether kids who only speak English are discriminated against and excluded from play.

Andy and Keshinee had their own individual inquiries but were not ready to talk about them. They openly shared that they would continue to read and think about death and divorce but were not ready to talk to others about their situations. The group supported them and moved back to talking and laughing at the possibilities of helping Zain with his survival pack and possible adventures.

The Overcoming Obstacles and Fear group shared an inquiry into fear and into reasons for not including children in play groups, but they also each had their own personal inquiries to pursue. “I wonder how we can connect what we do in lab to what is happening in class. My big question is that journeys and the text sets bring forward much of our personal emotions and I must admit that I am not at ease with this aspect. So, if children study content-based themes, are emotions associated with these themes? If we bring to the front our emotional beings instead of our intellectual beings, how do we as teachers handle this?” asked Armand. The power of a small group discussion around a text set is that children are in a collaborative context where they can think together, and still they have their own personal space where they can grow as learners to pursue their personal inquiries.

Final Reflections

The use of a broad concept and the text sets provided a learning context that encouraged critical thinking about issues important to each individual but within a shared focus. The literacy lab provided this collaborative context for children just as the study group provided a collaborative context for each teacher where they could ask questions and pursue personal inquiries. “In our weekly study group we have grown to value the trust built over time. It’s the confidentiality which binds the group and allows a certain freedom to share personal connections, to look for personal connections, to ask each other for ideas and share our failures,” remarks Laura. For some teachers these inquiries focused on new ways to talk with children, the significance of mother tongue for personal stories, and teaching as a conversation rather than a lecture. “Study group has given me the confidence to explore new ideas, put into place practice based on my beliefs that will benefit children. One of those beliefs is to value mother tongue and work collaboratively with class teachers to find personalized strategies for each EAL child,” emphasizes Dini. Others focused on how learning takes place when children are ready to take on challenges even though teachers might not completely understand a particular kind of a learning environment. “I feel my professional experience is at stake. It seemed that I was overlooking kid’s interests and I was just delivering what I wanted kids to learn. I thought I knew what was best for my kids without hearing their voices. As a child, I had just listened to my teachers and never had a voice,” writes Bindoo.

As a study group, we want to build on our learning by focusing on the use of a variety of organizational tools for generating ideas as well as responding to ideas. We want to encourage children to think using talk and written responses, organize thoughts on webs, lists and time lines, draw scenes, and sketch their thinking about issues. “When children are freed from thinking to search for the ‘right answer’ and begin to think for themselves, then they will want to connect their thinking and communicate,” said Elizabeth. Through using multiple tools for thinking and responding we hope to send the message that learning occurs through multiple ways of knowing and that these tools can be powerful ways to continue their personal inquiries within class-based units or themes.

Professional References

Short, K. & Burke, C. (1991). Creating curriculum. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Short, K. & Harste, J. (1996). Creating classrooms for authors and inquirers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Short, K., Schroeder, J., Laird, J., Kauffman, G., Ferguson, M., & Crawford, K. (1996). Learning together through inquiry: From Columbus to integrated curriculum. York, ME: Stenhouse.

Thomas, L. (2008). Creating a vision of possibility as professional learners. WOW Stories: Connections from the Classroom, (1)2. Retrieved November 12, 2008, from at http://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi2/?page=3.

Children’s Literature

Bunting, E. (1996). Summer wheels. Ill. T. Allen. New York: Harcourt.

Choi, Y. (2003). The name jar. New York: Knopf.

Cole, B. (1997). Prince Cinders. New York: Putnam.

Cooney, B. (1985). Miss Rumphius. New York: Puffin.

De Paola, T. (1988). Oliver Button is a sissy. New York: Harcourt.

Dyer, J. (2002). Five little fiends. London: Bloomsbury.

Egan, T. (2007). The pink refrigerator. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Golenbrock, P. (1992) Teammates. Ill. P. Bacon. New York: Sandpiper.

Martin, B. & Archambault, J. (1998). The ghost-eye tree. Ill. T. Rand. New York: Holt.

Watt, M. (2006). Scaredy Squirrel. Toronto: Kids Can Press.

Wheatley, N. (2001). Luke’s way of looking. Ill. M. Ottley. LaJolla, CA: Kane/Miller.

Woodson, J. (2001). The other side. Ill. E.B. Lewis. New York: Putnam.

Gloria Kauffman was the staff developer/curriculum coordinator and a PYP International Baccalaureate curriculum trainer at Clavis International Primary School in Mauritius. Currently she is the curriculum coordinator/language specialist and PYPIB curriculum trainer in Batam, Indonesia.

Krish Boodhram is a year 5 (grade 4) classroom teacher; Armand Bronqueur was a year 5 (grade 4) classroom teacher but currently teaching year 4 (grade 3); Laura Ponder Burgess is a parent volunteer and resident horticulturist;Elizabeth Caselton is a drama and movement teacher; Bindoo Caullychurn is a year 5 (grade 4) classroom teacher; Dini Lallah is the English as an Additional Language teacher for years 3-6 (grades 2-5); and Kim Han Wai Sang was the French teacher for year 3 (grade 2) but currently is teaching French in year 4 (grade 3). All are with the Clavis International Primary School in Mauritius.

WOW Stories, Volume II, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesii2/.