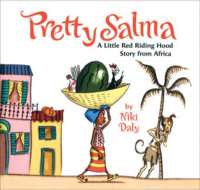

Pretty Salma: An African Little Red Riding Hood Story

By Judi Moreillon, Texas Woman’s University

In 2008, the United States Board on Books for Young People (USBBY) selected Pretty Salma: An African Little Red Riding Hood Story for inclusion on the Outstanding International Books (OIB) for children and young adults. This book was recommended for grades K-2. The book jacket notes Pretty Salma is set in West Africa and a brief glossary with two Ghanaian words accompanies the book’s dedication “For Salma.” The book is shelved in the 398.2 section of the library indicating that the Library of Congress determined it is a folktale originating in the oral tradition.

In 2008, the United States Board on Books for Young People (USBBY) selected Pretty Salma: An African Little Red Riding Hood Story for inclusion on the Outstanding International Books (OIB) for children and young adults. This book was recommended for grades K-2. The book jacket notes Pretty Salma is set in West Africa and a brief glossary with two Ghanaian words accompanies the book’s dedication “For Salma.” The book is shelved in the 398.2 section of the library indicating that the Library of Congress determined it is a folktale originating in the oral tradition.

Young Salma, who lives with her grandparents, is sent to the market by Granny who warns her not to talk to strangers. On her way to market, Salma sings a sweet song (tailor-made for storytellers to include in their retellings). At the market, she buys a watermelon, a rooster, a pink drink, and a bunch of straws.

She sets off for home with a heavy basket. Hot and taking a shortcut, Salma meets Mr. Dog who offers to carry her basket. Mr. Dog asks for Salma’s sandals, her wrap-skirt, her scarf, and her beads. He demands that she teach him her song and won’t return her things until he learns to sing it well. When she begs for her clothing and her basket, Mr. Dog threatens to bite her in two.

Salma runs until she finds her grandfather telling stories and wearing his Anansi costume. Grandfather and Salma hatch a plot to save Granny from Dr. Dog. Salma dons the mask of “the Bogeyman” and beats on Anansi’s drum, Grandfather shakes his rattles, Little Abubaker claps sticks, and they march home making quite a racket.

Meanwhile, Mr. Dog arrives at Granny’s house. When Granny asks for a kiss, Mr. Dog obliges her. “What a wet nose you have!” she exclaims. Famished, Mr. Dog chases the rooster. “My what an appetite you have!” exclaims Granny. Granny gives Mr. Dog a bath and becomes suspicious when she discovers his tail.

To test his authenticity, she asks “Salma” to sing their song and realizes she’s been tricked when all Mr. Dog can do is “Woof! Woof! Woof!” Granny attempts to chase Mr. Dog with her broom, but he threatens to bite her in two. Granny jumps into her cooking pot, and Mr. Dog snaps the lid closed and begins to make Granny soup. Just then “the Bogeyman” and his gang burst through the door and scare Mr. Dog, who turns tail and runs back “to the wild side of town.” And yes, Salma learned her lesson!

This story seems to have been written to be told. The repeating song, the sounds, the Ghanaian words, and rhythm of the story provide an opportunity for a dramatic retelling. What are your ideas for bringing this story to life through oral storytelling?

Reteller-illustrator Niki Daly lives in Cape Town, South Africa. He has written and illustrated many children’s books that involve various African cultures. His cartoon-like illustrations for Pretty Salma convey both a modern urban as well as aspects of a more traditional Ghana setting and portray various aspects of the culture, including fabric patterns and masks. The book itself does not provide any information about his folktale beyond what is mentioned in this review. I did find a post on Niki Daly’s blog about reading the book to school children while someone translated the story into Afrikaans. I noticed that you can leave Mr. Daly a note by clicking on his “About” page.

How can storytellers authentic this story? Are there other “Little Red Riding Hood” stories from Africa? One possible option for making connections and further research on aspects of this story is to investigate West African folklore centered on Anansi, the trickster African god who often appears in stories as a spider. Many popular children’s book authors and illustrators have retold Anansi stories including Eric Kimmel, Janet Stevens, and Gerald McDermott, who earned a 1973 Caldecott Honor Award for Anansi the Spider: A Tale from the Ashanti (Henry Holt, 1972). What do you know about this popular character from African (and Caribbean) folklore? What African folktale picture books have been written or illustrated by non-white Africans?

Next week’s title will be Juan Bobo Goes to Work: A Puerto Rican Tale/Juan Bobo busca trabajo retold by Marisa Montes, illustrated by Joe Cepeda.

Works Cited

Daly, Niki. Pretty Salma: An African Little Red Riding Hood Story. New York: Clarion, 2006. Print.

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit archival stream.

- Themes: Judi Moreillon, pretty salma

- Descriptors: Books & Resources, Student Connections, WOW Currents

Pretty Salma is a beautifully rendered retelling of Little Red Riding Hood that is a sharp contrast to the classic version. The classic Little Red Riding Hood takes place in the deep, dark wood where Little Red is walking all alone to her grandmother’s house, whereas Pretty Salma is a bright, airy, colorful retelling of this classic cautionary tale. Pretty Salma fills the senses as it projects the culture of Ghana as it depicts the bright clothing, colorful food filled open air markets, bustling buildings, song, native vocabulary and onomatopoeia; the reader becomes immersed in the world of Pretty Salma.

The cultural authenticity of Pretty Salma, for me, immediately comes into question with this story as it is an African rendition of a European classic fairy tale. There are no supporting documents to support that Pretty Salma is story born out of African folk tales, nor was I able to find any other similarly themed stories from Africa, however, I feel that Pretty Salma achieves a certain degree of cultural authenticity through the ways it diverts from its European inspiration. One of my favorite ways Pretty Salma diverts from the classic Little Red Riding Hood is how Pretty Salma and her grandfather deal with Mr. Dog (the big bad wolf). Rather than chopping off Mr. Dog’s head with an ax, Pretty Salma dresses up as Ka Ka Motobib, the African Bogeyman, Salma’s grandfather dresses up as Anansi, the African trickster and with the help of a friend who uses clapping sticks to making a loud kattack-attack sound, they scare Mr. Dog into leaving granny’s house. By mixing the caution of the classic Little Red Riding Hood with a dash of the trickster Anansi, and the vibrancy of West Africa, Pretty Salma becomes an African trickster story all its own.

References

Daly, N. (2006). Pretty salma; a little red riding hood story from Africa. New York,

NY: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 9780618723454

Dr. Moreillon,

You asked, “Are there other ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ stories from Africa?”

According to the research of Jamshid J. Tehrani (2013), there are African versions that resemble the “Little Red Riding Hood” folktale, but those versions AND “Little Red Riding Hood” have evolved from an older folktale called “The Wolf and the Kids”.

Tehrani (2013) also lists, in a link to Table S1, tales that he used as reference sources, which include the following:

Frazer, J. (1889). “A South African Little Red Riding Hood”. The Folk-Lore Journal 7: 167-168.

AND

Thomas, N. T. (1913). “Little Red Riding Hood”. Anthropological Report on the Ibo-Speaking Peoples of Nigeria, Part 3. London: Harriss & Sons, pp. 82-84.

As you stated, “Pretty Salma: A Little Red Riding Hood Story from Africa” is set in Ghana, a West African country, so it is interesting that this second source of Tehrani’s is based in Nigeria, which is near Ghana.

I found Tehrani’s article more difficult to understand with its technical jargon and incredible detail, but there are several other news articles that report on his findings and are easier to comprehend, such as the Huffington Post article in my references below. I also was fascinated by Tehrani’s tree diagrams which show how the tale branched off and spread.

I hope someone will check out these articles and tell me what they make of it all.

References

Gannon, Megan. 2013. “”Little Red Riding Hood” Tale Dates Back to First Century, Math Model Suggests.” Huffingtonpost.com, accessed March 24, 2014, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/11/14/red-riding-hood-math_n_4275490.html.

Tehrani, Jamshid. 2013. “The Phylogeny of Little Red Riding Hood.” PLOS One 8 (11): March 24, 2014. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078871.

This story would be a fun story to tell orally. As Dr. M. mentions, the rhythm of the story and the repeating song and sounds would engage children from start to finish. A way to further engage the students would be with props. Using items like the ones that Salma puts on at the beginning of the story (scarf, ntama, beads and sandals)would add a fun element. Having a mask like the one Salma’s grandfather wore would also interest the audience.

Putting a tune to Salma’s song and being expressive with all the different sound words would make the retelling fun and entertaining.

After telling the story, the children could create their own Bogeyman masks.

Daly, Niki. Pretty Salma: An African Little Red Riding Hood Story. New York: Clarion, 2006. Print.

Niki Daly’s Pretty Salma: A Little Red Riding Hood Story from Africa is rich with vibrant illustrations depicting a bustling Ghanaian urban market and rhythmic text infusing the emotion and energy of the region into this familiar tale. I agree with Dr. Moreillon when she writes that it seems this story was written to be told aloud; Daly’s text pulses with both song and sound that nearly demand to be brought to life by the reader or storyteller. While reading the book to myself, I found it nearly impossible to not sing Salma’s song aloud. In addition, Daly’s use of onomatopoeic words throughout the text, such as the “floppety-flip, flippety-flop” (p. 13) of Salma’s yellow sandals and the “Goema goema!… Shooka shooka! …Kattack-aatack!…” (p.19) of Grandfather’s musical instruments, provide many opportunities for a storyteller to delight an audience. I imagine as a storyteller, it would be great fun to bring the antagonist of the story, Mr. Dog, to life. If I were telling this story, I would play on the humor of Mr. Dog’s inability to sing Salma’s song; “All he could do was go, Woof! Woof! Woof!” (p.15) While reading the story, this image struck me as particular funny and as one that would translate well to an oral telling of Daly’s story.

My curiosity about the origins of the Little Red Riding Hood story was peaked when I read an article in which Daly explains that when he was developing the story idea for Pretty Salma, he was reminded of two traditional tales, Little Red Riding Hood and Mbulumukhaza, a tale told by the Tsonga people of North South Africa (Brian, 2008). Although I could not find any more information about the African tale, Mbulmukhaza, I did find interesting research by Tehrani (2013), where he attempts to analyze the evolutionary patterns of African stories with similarities to Little Red Riding Hood. One example is a folktale from Botswana, which similar to Little Red Riding Hood, warns children against talking to strangers and has a villain who uses trickery to try to eat the protagonist (Frazer, 1889). Perhaps due to the oral tradition of African tales, I have found it difficult to research and find many African tales that are similar to Little Red Riding Hood.

References

Brain, Helen. “How Children’s Writers Find Ideas.” suite. (2008). Accessed March 08, 2014. https://suite101.com/a/how-childrens-writers-find-ideas-a54948

Frazer, J.G. “A South African Red Riding Hood.” The Folk-Lore Journal 7 (1889) : 167-168. http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Folk-Lore_Journal/Volume_7/A_South_African_Red_Riding_Hood

Tehrani, Jamshid J. “The Phylogeny of Little Red Riding Hood.” Plos ONE 8, no. 11 (2013) : 1-11. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed March 25, 2014).

Pretty Salma: A Little Red Riding Hood Story from Africa

Pretty Salma is a lively and engaging story. Based in Ghana, the author Niki Daly sets a lovely scene for this West African version of “Little Red Riding Hood.” According to Hazel Rochman at Booklist (2007), this story “shows a mixture of the traditional and the contemporary in a Ghanaian urban setting.” This allows the readers to encounter a vast mixture of sounds, colors, textures, and personalities. Rochman (2007) also notes that this is a “fractured fairy tale,” and as mentioned above by Dr. Moreillon, the book is shelved in the 398.2 section of the library.

Salma visits the market and buys several different things, including food and drinks, giving the reader more insight into the climate and culture of the setting. Encountering the tricky “Mr. Dog” sets the traditional and familiar scene of meeting the “Wolf” in Little Red Riding Hood. However, the tactics used to foil Mr. Dog are localized to Ghana, as Salma and her Grandfather utilize scary wooden masks and raucous musical instruments that reflect that specific culture.

The Anansi West African trickster (Spider) god, as reflected in the mask that Grandpa wears, plays a prominent role in African Literature. A search conducted in the Children’s Literature Comprehensive database (CLDC 2014) for “Anansi” yields over 700 results, many of which contain the trickster’s name in the title, or are stories which answer the question: “How can we foil the tricky Anansi?”

An article by Marshall (2007) argues that Anansi the Spider god originated with the Asante (Ashanti) people of Ghana, and further: “demonstrate[s] the ways in which [Anansi] directly reflected key elements of Asante thought and culture.” The presence of Anansi in Pretty Salma lends cultural credibility to the story. The Anansi mask and the musical instruments, as well as the onomatopoeic sounds conveyed in the story, also add wonderful, vibrant details that bring the story to life and help to portray an authentic portrait of the culture.

CLDC, LLC. 2014. “Children’s Literature Comprehensive Database (CLDC).” Accessed 25 March

2014, via TWU Library Online.

Booklist. 2007. “Pretty Salma: A Little Red Riding Hood Story from Africa” by Niki Daly. Book Review by Hazel Rochman. http://www.booklistonline.com/Pretty-Salma-A-Little-Red-Riding-Hood-Story-from-Africa-Niki-Daly/pid=1871439

Marshall, Emily Zobel. 2007. “Liminal Anansi: Symbol of Order and Chaos.” Caribbean Quarterly 53, no. 3: 30-40. Literary Reference Center, (accessed March 26, 2014).

In the assessment of whether or not Pretty Selma was culturally authentic or not, I thought of the website Africa Access Review (http://africaaccessreview.org/). Africa Access is a not for profit organization that that reviews books and gives awards for children’s books that are set in Africa. Their mission is to improve the quality and authenticity of books about Africa, in order to better educate parents, librarians and teachers about Africa and the depiction of Africa in children’s stories and illustrations. Although Pretty Selma was not itself reviewed on this site, other books by Niki Daly were reviewed, which gave me some insight into the author. For example, the site reviewed The Herd Boy (Daly) which supplies many cues to a favorable authenticity, such as Daly being able to incorporate the everyday life of a young boy and his family, as well as authentic depictions of the veldt/grassland of the countryside, including culturally accurate traditional Xhosa designs and homestead depictions of traditional Xhosa dwellings. The reviewer states that Daly used some creativity in expressing the protagonists outfits, but to Daly’s credit, admitted that he was a cultural outsider and had to do extra steps to research for culturally accurate depictions of the Xhosa culture. Thus, this well-reputed website for African authenticity gives Daly a big thumbs up for cultural authenticity when writing about African cultures that differ from his own background. In fact, this review also mentions that Daly published the first picture book in South Africa that had a black child as a protagonist. Thus, although this site did not review Pretty Selma itself, it was a useful tool in learning more about Niki Daly’s reputation for cultural accuracy, which can be used to infer the amount of research and care that he would have needed to create Pretty Selma.

Works Cited

Baldwin, Carl. “The Herd Boy.” Africa Access, 09 Feb 2014. Web. 26 Mar 2014. .

Daly, Niki. The Herd Boy. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Books for Young Readers, 2012. Print.

Daly, Niki. Pretty Salma: An African Little Red Riding Hood Story.New York: Clarion, 2006. Print.

Niki Daly’s, Pretty Salma: A Little Red Riding Hood Story from Africa (2006) is an excellent picture book to teach children a part of West African culture by using a familiar tale. Many children have heard the Little Red Riding Hood story and Pretty Salma follows along similar plot lines with a few words in the Ghanaian language for children to learn. A simple, four lined song is repeated throughout the tale which encourages children to sing along with the storyteller and hold their attention. The story is well told using simple dialog and provides enough clues for children to anticipate what will happen next. The story is illustrated using vibrant, yet pastel colors to depict the clothing, buildings, automobiles, and costumes with just enough blank space on the page to not crowd the text and enhance focus on the importance of each scene. The addition of props such as wearing a head scarf or a colorful wrap skirt, showcasing a basket with some of the items from the story or an African mask and drums while playing West African instrumental music in the background, the storyteller of this tale will surely captivate the audience and create a cultural learning experience.

Even though the title of the story states that the setting is in Africa and Ghanaian words are used, my lack of knowledge of the culture did not allow me to immediately pinpoint the story’s cultural authenticity on my first reading. I found that by looking at the illustrations alone, the people, clothing, foods shown, buildings and automobiles and tropical setting could all have been set in Cuba, Jamaica or another Caribbean country. However, on the second reading I was able to find a visual clue to the story’s cultural authenticity embedded within the illustrations. On the scene on page 10, a man is shown wearing a yellow T-shirt with the image of the continent of Africa colored red, green, yellow and black and the words “AFRICA VIVA”. I verified the colors on the national flag of Ghana using the government of Ghana official portal and found that it too has a red strip on top, a yellow strip in the middle, a green strip on the bottom and a black star in the center (Ghana, 2013). This may not be an accurate way to judge a picture books cultural authenticity, but I believe it was a clue to that authenticity intentionally left by the author and illustrator of the tale.

References

Daly, Niki. Pretty Salma: An African Little Red Riding Hood Story. New York: Clarion, 2006. Print.

Ghana, (2013). Government of Ghana Official Portal. The National Flag. Web. 25 March 2014. Retrieved from .

Amy Staples,

Thank you so much for bringing up Tehrani and his work! I also was exploring and researching the topic of the evolution of the “Little Red Riding Hood” folktale and came across and article from this same author.

Tehrani writes in the Atlantic (2013) that folktales are told and retold repeatedly through the ages, but that every time it is told, it changes just a little. He brings up the point that the tales are spread both through the generation, and through entire societies over the whole world.

Little Red Riding Hood is one such oikotypes (international tales with lots of regional variations). Tehrani’s point is that we can study these folktales just like a scientist can study how biological species evolve.

I thought this article spread some light on just how global this particular folktale it. However, I disagreed with Tehrani’s premise that folktales could be used to trace the development and evolution of societies through the retelling of stories. One problem with this theory is that sometimes cultural outsiders retell a story on behalf of a people.

Thanks for the lively discussion!

Deborah

Works Cited:

Tehrani, Jamie. “Do Folktales Evolve Like Biological Species?.” The Atlanatic. Atlantic Monthly, 15 Nov 2013. Web. 27 Mar 2014. .

This story, set in Ghana, West Africa is full of references which firmly ground it in the West African setting. Among those are the spider Anansi, which Grandfather was dressed up as. According to Wikipedia, Anansi is “a West African God who often takes the form of a spider. He often takes the shape of a spider and is considered to be the god of all knowledge of stories. He is also one of the most important characters of West African and Caribbean folklore” (Anansi, 2013). In the Wikipedia information, “Anansi tales are believed to have originated with the Ashanti people of Ghana” (Anansi, 2013). Two of the Anansi stories explained in this Wikipedia post are How Anansi Got His Stories and Anansi and the Dispersal of Wisdom. Wikipedia lists many stories and gives titles of books based upon Anansi stories.

According to Michael Auld’s website of Anansi stories, Kweku Anansi is the son of the great Sky god, Nyame who turned his prankster son into a spider to teach him a lesson. His mother was the Asase Ya, the Earth goddess. This website contains a profile of Anansi which lists his time of birth as “around the time when animals and humans spoke to each other”, and his profession as “trickster”. Anansi has many powers, among them being the power to bring rain, the “Keeper of All Stories” (Anansi Stories, 2007). Anansi has a habit of getting himself into trouble and then having to use his wits to get himself out of the situation. I found this to be a very appropriate link to the character of Pretty Salam, since she got herself into difficulties because she foolishly did not listen to her granny (10), then had to use her wits to fix the problem (18).

I thoroughly enjoyed read Pretty Salma. Daly portrays Salma as a strong protagonist who is not afraid to seek help when she needs it. Pretty Salma is a clever and a resourceful character who defeats Mr. Dog through her wits rather than using violence. Even though she initially created her problem by ignoring her granny’s advice, Salma came up with a plan and enlisted the help of Grandfather in his Anansi costume to outwit Mr. Dog and save her granny(18). I think Pretty Salma makes a great role model for young girls. The lesson that Salma learns about following Granny’s advice gently nudges youngsters in the direction of listening to direction from their elders.

This oral story has so many possibilities as a re-telling. I would use masks for the characters as I told the story, and involve the listeners in the repetitive song, the “”Goema, Goema “ of the atumpan, the “Shooka Shooka” of the rattles, and the “Kattack-attack” of the clapping sticks (19). I would then follow up the story telling with a craft activity, allowing students to make their own versions of an Anansi or Ka Ka Motebi Bogeyman mask (18). This story would also make a great reader’s theater for the audience members to act out after designing their own costumes.

References

“Anansi.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 18 Mar. 2014. Web. 28 Mar. 2014. .

“Anansi Stories.com.” Anansi Stories.com. Michael Auld, 2007. Web. 27 Mar. 2014. .

Daly, Niki. Pretty Salma: A Little Red Riding Hood Story From Africa. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2007.

Deborah Carter,

Thank you for sharing the African Access Review website information! What a valuable resource to have access to!

Dr. M. & Kim Copeland,

I couldn’t agree more that this story is an ideal one to tell orally! With Granny and Salma’s favorite song, the flipping noises of the sandals, the sounds of the instruments, and the noises accompanying the scare tactic mission of Salma, Grandfather, and the children with instruments and masks, the auditory senses are sure to be stimulated in an oral re-telling.

Kim had some great ideas for props to use. I also thought of using old white towels and sharpie markers to create authentic Ghanaian textile patterns for head wraps and the ntamas (wrap-around skirts). Throw in some rattles and clapping sticks and homemade masks, like Kim suggested, and we could create a live, mirror version of Grandfather telling stories to the village children. How fun AND educational!

Kim,

To piggyback on your comment and Dr. M’s introduction, I agree that readers and listeners of this story could really benefit from hearing it told orally. Your idea about using the props as enhancements is a great one, as well as making the Bogeyman masks afterwards. Any sort of props would lend a dramatic air to this story, even a Mr. Dog mask or a basket full of “market things.”

The elements of the story that stood out to me the most were the sounds that the instruments made: “goema goema!” and “shooka shooka!” and “kattack-attack!” (pg. 19). I love the onomatopoeia and can imagine the way the instruments look, just based on these sounds. Being able to track down some of these instruments, or ones that make similar sounds, or even to reenact these sounds using hand claps and lap slaps, would add a lot to the story’s presentation and make it even more memorable. The rhythm of the story words, especially the dialect words and sounds, place the listeners directly into the story setting.

I like your idea of putting a tune to the song that Pretty Salma sings, and I wonder what your version sounds like! I bet there are a lot of different variations of that “song” based on who’s doing the telling, and I wonder which ones sound similar. Great discussion!

Daly, Niki. Pretty Salma: An African Little Red Riding Hood Story. New York: Clarion, 2006. Print.

Dr. M.,

You asked “How can readers authenticate this story?”

One of the ways to look for cultural authenticity is to see if the artifacts of the story are true to its setting. In Pretty Salma, Daly introduces us to two Ghanian words in the forward: ntama- a wrap-around skirt, and Atumpan- a talking drum. When you check the tourism website for Ghana (Touringghana, n.d.) you find that the wrap-around skirt is commonly worn, and drums are important in Gahnian music.

Another way to gauge the merit of the work is by looking at the awards and reviews the author has earned for this story, which you listed in the original post. My group also discussed the cultural authenticity of the family unit portrayed in Pretty Salma: A Little Red Riding Hood Story From Africa. One theme of the story which is culturally accurate for Ghana is the importance of the family unit according to the faimly.jrank.org web page I found on Ghana family structures. Although in this story, the family consisted of Granny, Grandfather and Pretty Salma, rather than a traditional nuclear family or even a traditional one, still the importance of the family is evident. While it is a mystery as to why Granny would have chosen to get into the soup pot to get away from Mr. Dog (25), we did find that soup is an important part of Ghanian cuisine (“Ghana” Travel ).

An interesting topic of discussion for us was about which came first: Pretty Salma or Little Red Riding Hood. While trying to discover the answer to this question, I found that there are even more versions of Little Red Riding Hood than I had realized, and even the Grimm version, (which most might assume was the original tale), might have been borrowed from another source. I decided to try to find out which version of “Little Red Riding Hood” came first, assuming that it was the Grimm version. I stumbled upon D.L.Ashliman’s website of “Little Red Riding Hood” versions, and found that while the Grimm version, Little Red Cap, no doubt preceded Pretty Salma, it was probably not original.

You also asked if there were other “Little Red Riding Hood” stories from Africa. Anthropologist Dr Jamie Tehrani claims that all “Little Red Riding Hood” versions, including the Grimm version and African versions may have descended from the same source- “The Wolf and the Kids” (Burrows). The article does not name the African versions, however. I cannot help but feel that with as many versions of “Little Red Riding Hood” are in existence, there must be others, and I just haven’t found them yet.

Whether or not there more versions, or which one came first, Pretty Salma” does appear to be culturally accurate, and is a delight to read.

References

Ashliman, D.L. “Little Red Riding Hoodand other tales of Aarne-Thompson-Uther type 333. N.p. . 1999. Web. 5 Mar. 2014. http://www.pitt.edu/~dash/type0333.html/.

Burrows, Ben. “Little Red Riding Hood May Have Relatives in Africa and Asia, Research Reveals.” Mirror News. Mirror Online, n.d. Web. 29 Mar. 2014. .

Daly, Niki. Pretty Salma: A Little Red Riding Hood Story From Africa. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2007.

“Ghana.” Travel Guide To, Africa. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 Mar. 2014. .

“Ghana – Family Structure, Family Formation, And Family Life.” – Ties, Lineage, Unit, and Marriage. Net Industries, n.d. Web. 29 Mar. 2014. .

“Touringghana.com – Ghan a Tourism Homepage.” Touringghana.com – Ghana Tourism Homepage. N.p., n.d. Web. 06 Mar. 2014. .

It was most difficult to response to Dr. Moreillon’s question of, “What African folktale pictures books have been written or illustrated by non-white Africans?” After doing some initial research, I was very surprised to discover that most African folktales had been written by Caucasian authors. This is true for African folktale stories that were written in the past and even those recent published.

In my research I used Google, Google Scholar, Wikipedia and finally stumbled upon the author Baba Wagué Diakité on Scholastics Authors and Books website. I found that Mr. Diakité is an African author who was born in Mali, West Africa but currently lives in Portland, Oregon (Scholastic, 2014). Mr. Diakité has written The Hunterman and the Crocodile: A West African Folktale (1998), The Hatseller and the Monkeys (1999), and The Magic Gourd (2005). He also illustrated I Lost My Tooth in Africa (2005) which was written by his twelve year old daughter Penda.

Even though I feel that authentic folktales are best told from the people of that culture, it is important to preserve these stories, no matter who is doing the preservation. It is much too important to have the stories written down and translated into various languages than to split hairs about the cultural affiliation of the author. As long as the author does his or her best to maintain the integrity of the original storyteller’s tale, that tale can be retold in a way that is best suited for the audience of interest to learn from and enjoy.

References

Diakité, Baba Wagué. The Hatseller and the Monkeys. New York: Scholastic, Inc., 1999. Print.

Diakité, Baba Wagué. The Hunterman and the Crocodile: A West African Folktale. New York: Scholastic, Inc., 1998. Print.

Diakité, Penda, & Illus. Baba. Wagué Diakité. I Lost My Tooth in Africa. New York: Scholastic Press, 2005. Print.

Scholastic. Authors & Books. Web. 29 March 2014. .

Many times stories are used to teach children a lesson. Reading this story about Pretty Salma I thought about what lessons children could be learn from the story. First of all, it is a cautionary tale. Salma learned to listen to her granny. Children will see the mistakes Salma made and a discussion about Salma’s choices would help them see why it is important to listen to adults.

Salma also used her wits to get herself out of the bad situation she had gotten herself into. Having a discussion about the different ways Salma could solve her problems helps children see that they can use their heads to think through situations. Children need to be empowered to solve their problems. Using folktales as cautionary tales is a great way to start the discussion.

Daly, Niki. Pretty Salma: An African Little Red Riding Hood Story. New York: Clarion, 2006. Print.

Dr. M.,

You asked “What African folktale picture books have been written or illustrated by non-white Africans?

I typed African folktale picture books into the search engine, and found the Powell’s Books website. They had a selection of 35 books fitting my criterion. Next, I looked through to find out how many of those books had been written or illustrated by non-white Africans. Of the Thirty-five books listed, I could find information to support that three were written by non-white Africans.

One non-white African author/illustrator I found is Baba Wagué Diakité. Wague was born in Bamako, Mali in West Africa in 1961. Some of the picture books he has authored or illustrated are: I Lost My Tooth in Africa, The Pot of Wisdom: Ananse stories, the Magic Gourd, The Hatseller and the Monkeys, Mee-An and the Magic Serpent, and The Hunterman and the Crocodile: A West African Folktale.

Nelson Mandela, South-Africa’s late, first democratically-elected president authored a collection of folktales in: Nelson Mandela’s Favorite African Folktales.

Another non-white African author is Chinua Achebe. Chinua Achebe was born in Nigeria in 1930. Achebe authored the African folktale picture book How the Leopard Got His Claws. Although he is listed as the author of many other books, they are mostly novels. I could not find any other children’s picture books by this author.

I found this research to be a bit disappointing. I really would have thought that a higher percentage of the books were written by non-white authors from Africa. I was not able to find enough information about some of the authors/illustrators to verify their ethnicity or place of birth. I also did not include African Americans in my research. More research on my part will be required to find out whether or not this is an accurate percentage.

References

“Children’s Picture BooksFolktales African.” Let’s Talk Books- Powell’s Books. Powells City of Books, n.d. Web. 30 Mar. 2014. .

There is something so pleasurable in Pretty Salma and how Daly takes a potentially violent situation (where Mr. Dog is threatening Granny) and resolves it with brains, family and friendship! As I have explored more of Africa’s many different cultures I have delved into many of the different Anansi stories that pepper African literature. I think it is telling of how a society approaches conflict when characters like Anansi, who often irritate, anger and inflame the other animals of his stories is rarely treated with violence. While Anansi often becomes entangled in his own tricks, he often learns a valuable lesson (or perhaps it would be more truthful to say that the readers/listeners learn a lesson) in the end. The readers/listeners see how trickery often gets nowhere and while you think you might deserve better than your neighbors – you probably don’t!.

“Anansi.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 29 Mar. 2014. Web. 29 Mar. 2014.