by Yoo Kyung Sung, The University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM

“I didn’t know what was happening in Asia during WW II. I had no idea Korea was under Japanese occupation!” Every semester I repeatedly hear this message from my preservice teachers after reading books like When My Name Was Keoko, by Linda Sue Park. I wonder, “How did they miss this in their American history courses?”

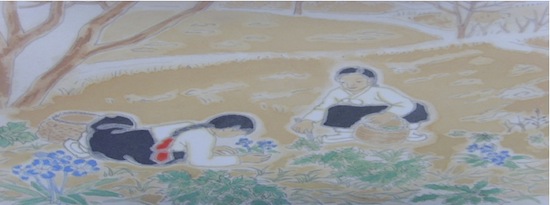

These comments, and the picturebook The Grandmother Who Loves Flowers by Yoonduck Kwon, were catalysts that led me to reflect on the childhood texts I read, as a young Korean schoolgirl, about the WWII Japanese occupation of Korea. Seeking the truth about our history was important to me, but it was also equally uncomfortable. The Grandmother Who Loved Flowers is based on the story of Dahl Yun Sim, a thirteen-year-old Korean girl, kidnapped by Japanese soldiers during WW II as she and her sister were out picking wild greens.

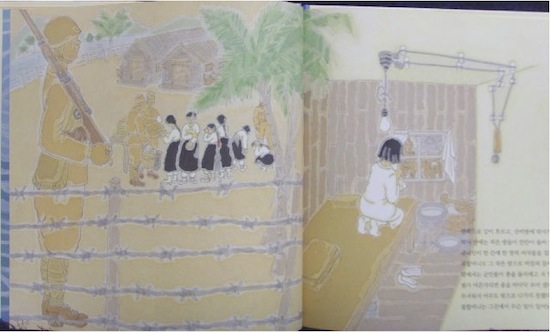

The recounting of how Dahl Yun Sim was forced into being a sexual slave for Japanese soldiers during WWII was disconcerting because she was but one of many young girls violated. Like my preservice teachers who lacked any familiarity with the Asian theater of WWII, I knew little of this myself when I was young. Literature like The Grandmother Who Loved Flowers simply wasn’t available in my childhood. I now wonder, “Why?” What my preservice teachers made clear to me was that, for them, what happened in Korea during WWII was considered of minor importance in American history texts. That, however, doesn’t explain Korean students’ lack of awareness. “How about my classes in Korea? Can we, as Koreans, acknowledge that we knew about sex slavery by the Japanese military without actually experiencing those stolen voices in our literature? ” Reading about it in the abstract as a historical recounting lacks the visceral reaction literature provides.

One explanation is that historical fiction in Korea, traditionally, has been an adult genre. Historical fiction, for children, was encapsulated in biographies – stories about historical heroes and heroines. A book like The Grandmother Who Loves Flowers is a welcome development in that it challenges the established notions of historical fiction in Korea. Experiencing parts of Korean history through ordinary people’s voices instead of concentrating on heroic characters is a new direction for children’s literature in Korea.

The book has a unique history. It is the first collaborative project developed by the Collaborative International Picture Book Project, a group of four authors from Korea, Japan, and China as well as a publisher from each of them. These three nations are geographical neighbors, yet their history is replete with disputes, conflicts, and war with each other. Bridging these age-old controversies is the Collaborative International Picture Book Project. Their purpose is “honest recording, sharing each other’s sadness, and moving forward for the peaceful future through the collaborative works among three nations”

The author of The Grandmother Who Loves Flowers, Yoonduck Kwon, should be familiar to her U.S. readers with My Cat Copies Me. Kwon describes the journey of publishing picture books around ‘peace and war’ as extremely challenging. Because nations have their own positions, biases, and perspectives on topics like war and it colors how they confront their history, a collaborative project demanded much persistence and courage. For example, it took four years to actually write the story. Twelve draft editions were produced prior to finally publishing The Grandmother Who Loves Flowers.

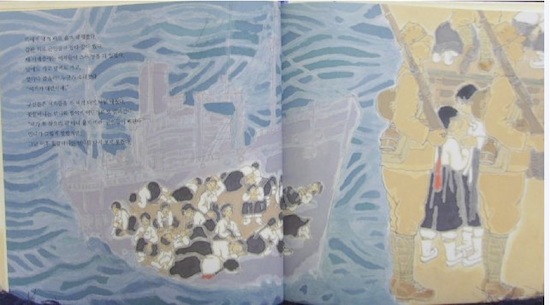

Dahl Yun Sim was 83 years old when she finally revealed what happened to the world. The title refers Ms. Sim’s love of flowers and how touching flowers became therapeutic. The Grandmother Who Loves Flowers reflects just one of the many stolen voices whose human rights were abused. Throughout, the book poetically and powerfully portrays the abducted girls’ uncertainty and confusion. Dahl Yun Sim’s story is a surrogate for not only all of the comfort women from Korea, but also those from other Asian countries, including China, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia, etc. who were similarly abducted during WWII. For her, the tragedy was compounded even further when she returned home after the war and Korean society refused to accept her. Ms. Sim, who recently passed away, is quoted in the book, saying “Nobody should have to go through I went through. I lost my life, but it was not my fault.”

The Grandmother Who Loves Flowers content is intense and potentially ‘controversial’ due to its picture book format, reminiscent of Faithful Elephants: A True Story Of Animals, People, And War, by Yukio Tsuchiya. Listening to these stolen voices, uncomfortable as they are, makes us rethink the meaning and the consequences of war. Classroom teachers in the U.S. can, moreover, use texts such as these to challenge stereotypes about Asian culture and enhance their students’ socio-political and cultural awareness.

References

Heo, M. K. (2010) Fruitful achievement, The Grandmother Who Loves Flowers. Hangyeorae Time.

http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/culture/book/425321.html retrieved December 5, 2010.

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit archival stream.

- Themes: historical fiction, Yoo Kyung Sung

- Descriptors: Books & Resources, Debates & Trends, Student Connections, WOW Currents

It is interesting to know that Japanese publisher felt uncomfortable and hesitated to publish the picture book dealing with comfort women in Japan because of their lack of knowledge about the comfort women. In Japan, “comfort women” is a critical controversial issue, only among politicians. Only authorities have argued the issue and many of them don’t acknowledge it and say, “There didn’t exist “comfort women”‘ or “They volunteered to become comfort women”. Some politicians have also claimed that ordinary people, especially children in Japan, don’t need to learn about it.

The picture book is going to publish in Japan soon. I think it becomes a powerful tool for people to know, learn, discuss the event and seek truth about the history by themselves in Japan.

Just as a follow-up, it took until 2018 for the Japanese translation to be published because the original publisher wasn’t comfortable doing it, and so a group crowd-sourced to raise the funds to do it. The Japanese translation is based on the 2015 edition of the Korean original. ISBN: 9784907239299 As of 2021 there is no English translation, and there really should be.

Hi Sharon,

That’s powerful to learn that a group of people funded the book project in Japan. I had a chance to meet the translator who worked on my article about books about comfort women for JBBY’s Bookbird journal also had to fight hard for the article to get published. I appreciate your follow-up on this.