by Yoo Kyung Sung, University of New Mexico Albuquerque NM

Why, in the classroom, is immigration often presented only as a parochial issue? Seldom do U. S. students read and discuss migration as a worldwide political and economic concern. Far too often their understandings of other countries are formed from easily generalizable geographical and cultural information. This denigrates the complexity of socio-political realities and the historical experiences of other countries. For example, they often reference Africa as one large nation instead of as a continent of many countries and diverse cultures. They are primarily aware of dominant groups within countries who, for their part, are frequently dismissive of others (i.e. Koreans in Korea dismissing non-Koreans). Sophisticated inquiry required for deeper understandings of global issues is too often neglected. I want to, then, introduce two books that may challenge such superficial assumptions about other nations.

Why, in the classroom, is immigration often presented only as a parochial issue? Seldom do U. S. students read and discuss migration as a worldwide political and economic concern. Far too often their understandings of other countries are formed from easily generalizable geographical and cultural information. This denigrates the complexity of socio-political realities and the historical experiences of other countries. For example, they often reference Africa as one large nation instead of as a continent of many countries and diverse cultures. They are primarily aware of dominant groups within countries who, for their part, are frequently dismissive of others (i.e. Koreans in Korea dismissing non-Koreans). Sophisticated inquiry required for deeper understandings of global issues is too often neglected. I want to, then, introduce two books that may challenge such superficial assumptions about other nations.

In both stories young Korean boys are living in other countries, though the stories are set in two different historical time periods. The first is the story of a thirteen year old in WWII near Ube, Japan working as a forced-laborer. The second story is of a boy who is a descendant of a Korean independence fighter and occurs during the Chinese Cultural Revolution in Manchuria. The struggle for both to retain their Korean identity in the midst of social upheaval is a core theme in both books. Such stories of young children during Korean Diasporas are new in Korean historical fiction. Moreover, voices that echo the sufferings of forced-laborers in WWII and the struggles of the descendants of Manchurian independence fighters are a radical departure in Korean children’s literature.

Why these texts are not available in English is an interesting question. In the U. S., the American experience of WWII in the Pacific is frequently limited to what occurred between Pearl Harbor and Hiroshima. Similarly, the Cultural Revolution involving Mao Tse Tung is just a “Chinese issue.” This should not be the dominant way of understanding the issues encompassing WWII and its consequences. These books represent the voices of a “foreign minority” forced on journeys of physical and cultural survival because of their diaspora status. The novels are written in Korean and are not likely to be published in the U. S. That is disheartening because stories like these can help us to deconstruct the common and simplistic conception of Asians as one homogeneous cultural group.

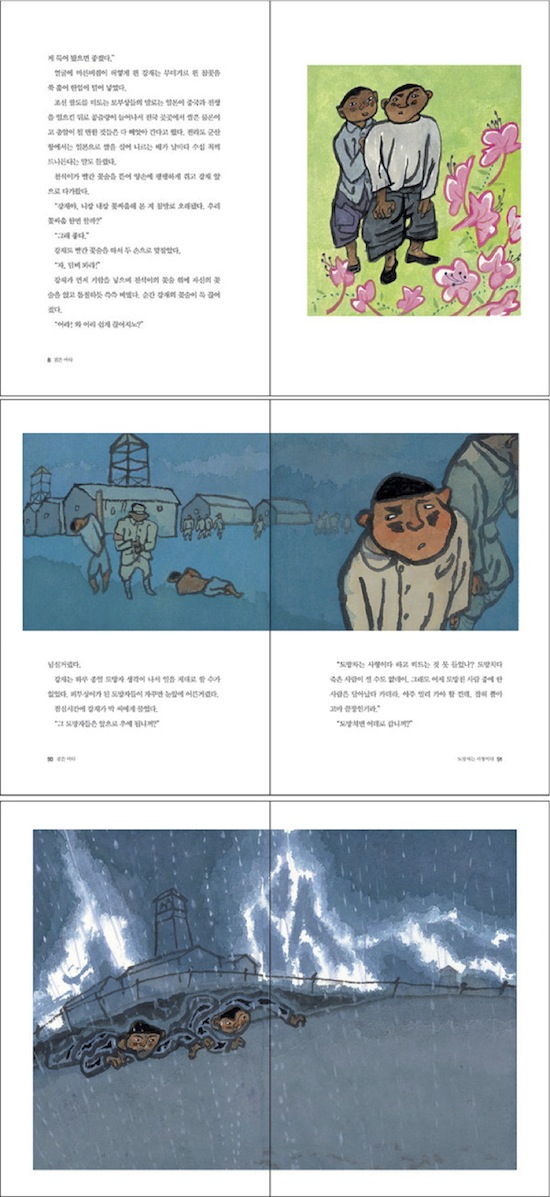

The Black Ocean (2010) relates the story of Chun Suk and his best friend Gahng Jae during WWII. Japan, in the middle of a war, desperately needed money, labor, and raw materials. To help fill that need young males in Korea were forced aboard ships heading to Japan to work in labor camps. Chun Suk, though too young, is asked to substitute for his big brother. His parents, concerned about his brother’s mental illness due to bullying at school, encourage him. In exchange, Chun Suk is told that he will have a position as a government official when he returns from Japan. His best friend, Gahng Jae, is kidnapped by the Japanese due to his mature look, height, and size and so was not even able to tell his parents goodbye. Filled with confusion, uncertainty, and fear, they are arrive in Japan to work in a mine drilled under the ocean floor by the Chosei Mining company. Naïve Chun Suk and Gahng Jae had hoped to learn valuable skills, yet they soon realize that they were merely slaves doing dangerous jobs for Japan. Despite rumors that the coal mine will collapse and flood, the oppressing conditions don’t change and security is, instead, tightened. Eventually, the tunnel collapses and the miners in the tunnel are all killed. The story is based on actual events, but public awareness of this incident is recent. Underwood (2010) reports this tragedy:

- The so-called “Water Emergency” (Mizuhijo) disaster, which occurred offshore near Yamaguchi’s Ube city in February 1942, has also lately come to public attention. One hundred eighty workers, 140 of them Koreans, were drowned in a massive tunnel collapse at Chosei Mining’s undersea coalmine. No remains were recovered.

Chun Suk and Gang Jae manage to escape, but end up separated. When reunited, Chun Suk sees that Gahng Jae has lost his hand and is suffering from shock after the detonation of the second atomic bomb in Nagasaki. Chun Suk manages to contact his parents and learns that his little sister was also taken for a “factory job” in Japan. Knowledgeable readers can reasonably infer that she was actually into forced sex slavery (“comfort girls”) for the Japanese military. Chun Suk’s fight to return home to Korea continues, but does not have a happy ending.

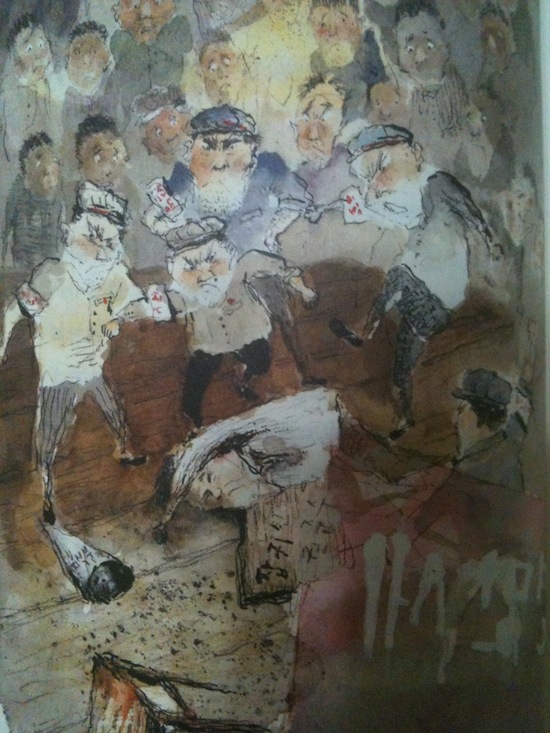

The other story, Kori Bangs: Korea Stick (2006) is about a Korean diaspora family who live in the Manchuria area in China. Geographically, parts of Manchuria border Korea. A series of early Korean dynasties held territory on the Chinese side of Manchuria. A small Korean community remained in this area. During the Chinese Cultural Revolution, minorities were forced to learn Chinese while the teaching of the Korean language and Korean heritage was prohibited. Burying diversity and tradition were the focus of Mao’s revolution. The protagonist, Dong Hyuk’s grandfather, was a Korean independence fighter. His uncle, a college professor, was in jail because expressing intellectual thoughts was a crime during the Cultural Revolution. His father was taken to a People’s Court. He was convicted for teaching that the Korean written language, Hanguel, was created by King Sejong. Treating history, knowledge, property, and capitalism as evil were hallmarks of the Chinese Cultural Revolution.

The other story, Kori Bangs: Korea Stick (2006) is about a Korean diaspora family who live in the Manchuria area in China. Geographically, parts of Manchuria border Korea. A series of early Korean dynasties held territory on the Chinese side of Manchuria. A small Korean community remained in this area. During the Chinese Cultural Revolution, minorities were forced to learn Chinese while the teaching of the Korean language and Korean heritage was prohibited. Burying diversity and tradition were the focus of Mao’s revolution. The protagonist, Dong Hyuk’s grandfather, was a Korean independence fighter. His uncle, a college professor, was in jail because expressing intellectual thoughts was a crime during the Cultural Revolution. His father was taken to a People’s Court. He was convicted for teaching that the Korean written language, Hanguel, was created by King Sejong. Treating history, knowledge, property, and capitalism as evil were hallmarks of the Chinese Cultural Revolution.

The title, Kori Bangs, is a phrase over one thousand years old that had served as a nickname for Korean descendants in China. In the story classroom peer pressure divides Chinese children and Korean children. It is exacerbated by the confusion of the Cultural Revolution and, as a result, “Kori Bangs” morphs into slang for bully. Later, Dong Hyuk’s grandmother and father teach him that “Kori Bangs” is a Chinese pronunciation for “Korean Stick.” Korean stick originated in an ancient Korean dynasty. Brave soldiers of that era used a “stick” that became the symbol of their heroic warrior style, in contrast with the usage of “Kori Bangs” as a synonym for bully. Dong Hyuk, his friends, and other Korean community members band together to save historic Korean treasures from destruction during the Cultural Revolution.

The voices of young children such as Chun Suk and Dong Hyuk are relatively new for readers in Korea. It is a welcome change that historical fiction is broadening its horizons to reflect our past and present. Perhaps, through this historical continuum, the stolen voices from Korean history occurring outside of Korea may help Korean children to understand non-Korean peers and the recent new phenomena of multiculturalism.

Reference

Underwood, W. (2010). Names, Bones and Unpaid Wages (2): Seeking Redress for Korean Forced Labor. Retrieved December 16. http://www.japanfocus.org/-William-Underwood/2225

Texts written by Young Sook Moon. She is a well known historical fiction writer.

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit archival stream.

- Themes: global migration, historical fiction, Yoo Kyung Sung

- Descriptors: Books & Resources, Debates & Trends, Student Connections, WOW Currents

One thought on “Confronting History: Young Korean Diasporas During WWII and the Chinese Cultural Revolution”