By Prof. Carmen M. Martínez-Roldán & Elizabeth Morphis, Teachers College, New York.

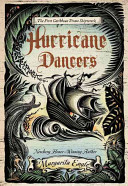

In this week’s blog, Elizabeth Morphis, a university student taking my Latino literature course, conducted a read aloud of the book Hurricane Dancers by Margarita Engle with six fifth grade students at a New York City public school. Here she shares some highlights of her experience. We hope that other teachers or readers will feel inspired to offer their thoughts regarding the use of historical fiction and of verse to reflect on the complexities of historical events.

In this week’s blog, Elizabeth Morphis, a university student taking my Latino literature course, conducted a read aloud of the book Hurricane Dancers by Margarita Engle with six fifth grade students at a New York City public school. Here she shares some highlights of her experience. We hope that other teachers or readers will feel inspired to offer their thoughts regarding the use of historical fiction and of verse to reflect on the complexities of historical events.

Elizabeth: I used the book Hurricane Dancers because the students had been studying the theme of exploration during the Age of Discovery in their social studies class. I selected this book because it offered a different perspective to the traditional narrative of the discovery that the textbook used in class was offering: a celebration of the European Explorers without any information about the native people nor the civilizations who were already living on the land before the Europeans arrived. The book was written through the lens of a native boy name Quebrado (The Broken One) who was half native and half Spanish. My goal was to introduce the students to a different viewpoint of the age of exploration and provide an opportunity to learn about a culture beyond their own.

Written in verse instead of prose, Hurricane Dancers is a collection of three fictional accounts of historical events surrounding the early Spanish exploration of America. The first story is about Quebrado, who has been enslaved and is seeking his freedom. After I read the first account, I asked the students to turn and talk to their partner about what they noticed about Quebrado, the main character. The students had understood that he was half native and half Spanish and the author explains that Quebrado’s name means “the broken one.” While listening to one conversation, I heard a student say “So, if his name means ‘the broken one’, who named him, his parents or the pirates [who had captured him]?” In general there was some confusion over why his name is “the broken one.” It struck me as interesting that the students were able to pick up on the uniqueness of his name and question how it was given to him. Another comment that I heard from a student was “I wonder if his father is ashamed that Quebrado is half native. Maybe that’s the reason his dad left him”. After only eight pages, the students were already questioning the motive for the father deserting his son. Through their questions of the book, the students were grappling with issues of power and authority that they saw in the treatment of Quebrado by the Spaniards. They were attributing his name and his abandonment by his father to the fact that he was a native rather than a European. As they continued sharing their interpretations, the students showed that they had begun to go beyond “extracting the public meaning of text” (Rosenblatt, 1982, p. 271), and they were producing their own meanings and understandings of the text. I was also happy to see their responses to a narrative written in verse, which they were not familiar in their reading of historical fiction.

We would love to learn about other readers’ experiences with Hurricane Dancers as well as other teachers’ use of this or other similar texts with their students.

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit archival stream.

- Themes: Carmen M. Martínez-Roldán, Elizabeth Morphis, Hurricane Dancers

- Descriptors: Books & Resources, Student Connections, WOW Currents