By Yoo Kyung Sung, University of New Mexico,

and Junko Sakoi, Tucson Unified School District

Last week we explored a range of Japanese picture books describing natural disasters. The books became significantly meaningful to children in Japan when the earthquake of 2011 occurred. Allowing time for thinking and talking about the earthquake through picture books developed even more meaning outside of school. Social outreach programs thru mobile libraries were essential for young readers as they, in part, ameliorated the effects of the earthquake for children who lost their schools and access to books. We’d like to explore the traveling library as a type of Japanese cultural artifact that will continue to be important in its future.

Book Access as Action Taking

Mobile libraries, depicted through picture books, may be more familiar in other global settings than in the U.S. Two powerful ones are Biblioburro: A True Story from Colombia by Jeanette Winter (2010) and Waiting for Biblioburro by Monica Brown (2011). Both books tell the true story of a librarian, Luis Soriano, who frequently carried a load of books on a donkey to reach young “patrons” in isolated rural areas of Colombia. The meaning of the library expanded beyond simply book availability to happiness and excitement when books arrived after a long wait. Mobile libraries convey their own magical charm and energy. The Japanese mobile libraries provide the same emotional reactions, especially for the victims of the March, 2011 earthquake. Authors and publishers have been important in retelling earthquake stories, especially through children’s books, so that earthquake victims and their communities areas are not forgotten as media interest inevitably fades away. Many children are still displaced from their home, particularly the area around Fukushima where radioactive contamination severely damaged the environment. No one, as yet, can guarantee when they will, if ever, return. Meanwhile, communities continue making books accessible for these earthquake victims through ongoing support of the mobile libraries.

About Mobile Libraries in Japan

In Japan, mobile library service first started in 1945 in the immediate chaos following World War II using cars and ships. It enabled people in distressed situations – no access to public libraries in rural communities, debilitating physical disabilities, residing in areas affected by natural disasters – to access to information, ideas, and stories (Ishikawa & Oiwa, 2012; Nakayama, 2006). The number of mobile libraries declined with the increase of traditional public libraries. Yet 559 mobiles are still delivering books around Japan every day (Japan Library Association, 2010). Each mobile library usually carries between 2000 to 4000 books, many of them children’s literature and kamishibai (Japanese traditional visual storytelling). A mobile library visits locations such as nurseries and elementary schools, public parks, shrines, nursing homes, hospitals, community centers, and sometimes even a person’s house once or twice a month, staying for approximately an hour at each stop. A person can check out ten to twenty books at a time.

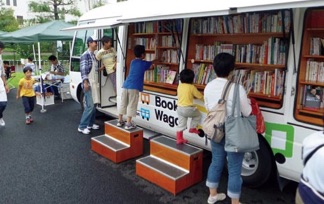

In the post-2011 disaster recovery period, mobile libraries played a significant outreach role in the Tohoku, Iwate, Miyagi, and especially the Fukushima prefectures (Kamakura, 2014). The earthquake and subsequent tsunami washed away many schools and libraries. People who were not in the disaster areas began to bring books to victims via Ehon Cars (smaller than a regular mobile library with more inherent flexibility for servicing a rural disaster area), Book Wagons, or Bookmobiles. Right after the disaster, Chieko Furuta Suemori, a former IBBY executive member, launched the 3.11 Ehon Project Iwate for children (Suemori, 2013; 3.11 Ehon Project Iwate, 2011). Ehon Project Iwate has delivered 232,000 books, which Chieko Furuta Suemori received from all over the country, using six Ehon Cars to children in evacuation centers and temporary shelters. When she encountered a boy who sought out a specific book, she remarked:

In the post-2011 disaster recovery period, mobile libraries played a significant outreach role in the Tohoku, Iwate, Miyagi, and especially the Fukushima prefectures (Kamakura, 2014). The earthquake and subsequent tsunami washed away many schools and libraries. People who were not in the disaster areas began to bring books to victims via Ehon Cars (smaller than a regular mobile library with more inherent flexibility for servicing a rural disaster area), Book Wagons, or Bookmobiles. Right after the disaster, Chieko Furuta Suemori, a former IBBY executive member, launched the 3.11 Ehon Project Iwate for children (Suemori, 2013; 3.11 Ehon Project Iwate, 2011). Ehon Project Iwate has delivered 232,000 books, which Chieko Furuta Suemori received from all over the country, using six Ehon Cars to children in evacuation centers and temporary shelters. When she encountered a boy who sought out a specific book, she remarked:

One boy kept on searching for one of his favorite books, and when he found it, he clasped it dearly as he left. I realized that the children were searching for their favorite picture books they had read at home, kindergarten or day care before the tsunami.

Each Book Wagon visited one place a day for a week from July 11, 2011 to March 31, 2012. Some librarians helped select the books that considered the various needs of the victims such as mental health issues, the appropriateness of picture books, and topics such as cooking, knitting, and gardening – all needed to rebuild an ordinary life. According to the data of 2012 by Toppan, the highest number of books lent was for picture books in the summer when children were out of school for vacation. In addition to Ehon Cars and Book Wagons, Shanti (a non profit volunteer association) ran three Bookmobiles in Fukushima, Iwate, and Miyagi beginning in July 2011 (Shanti, 2015). Each of their Bookmobiles carries around 1,500 to 2,000 books and visits eight places once every week. Thus, Ehon Cars, Book Wagons, and Bookmobiles have created a “Salon Space” (Toppan, 2012, p. 9) for displaced people in Tohoku – they browse books, share storytelling time, exchange information, connect with other people, and enjoy conversations.

Meaning of Promoting Importance of Continuity in Literacy Practice

When we think of mobile libraries, we may think of books being checking in and returned. While this was what was intended, it has become so much more by creating community among residents living in temporary housing that provides “mental support for victims” (Toppan CSR Report, 2012). When we experience our own sense of place, it is not just about the space, but also the people around us. Weekly visits by Ehon Cars or Book Wagons initiates conversations among members in this “Salon Space” and prepares them to move forward. Although this format of a moving library may appear to be a new trend associated the 3.11.earthquake, Japan has a long history of outreach for the purpose of providing comfort and help to its citizens as they work to return to a normal life. We have interpreted such outreach programs as reflecting a well-established outreach with significant historical and cultural roots to care for disaster-impacted regions. Clearly, Japan has developed socially resilient systems to cope with countless earthquakes that, whether weak or strong, evoke worry and fear. As Japan developed strong systems to minimize consequent loss and damages, support for victims’ mental recovery is one of them.  This trend builds on Kamishibai as one of those resilient systems that individuals developed. Kamishibai goes back to the 1920s, right after the Great Kanto Earthquake around Tokyo that contributed to a long-term economic depression in Japan. What began as individual “entertainment” businesses telling stories with enlarged index card images became the springboard for Japan’s famed animation and manga industries.

This trend builds on Kamishibai as one of those resilient systems that individuals developed. Kamishibai goes back to the 1920s, right after the Great Kanto Earthquake around Tokyo that contributed to a long-term economic depression in Japan. What began as individual “entertainment” businesses telling stories with enlarged index card images became the springboard for Japan’s famed animation and manga industries.

There are many different iconic items and images of Japanese culture like sushi, Toyota, kimono, ninja etc. We hope mobile libraries eventually become yet another cultural icon representing Japanese resiliency. Natural disasters happen quickly, yet recovery often involves extensive structural and emotional rebuilding. Ecologically and historically Japan exists in an area prone to earthquakes. The socially constructed cultural ethos that supports community resilience found in various types of resistances–resistance to being demolished, resistance to being helpless, resistance to being forgotten etc. demonstrates the power of a nation that has grown and has been strengthened by viewing a crisis as a “resource.”

Reference

3.11 Ehon Project Iwate. (2011). The “Ehon Car” (Picture Book Car) Project. Chieko Furuta Suemori & JBBY. Retrieved from http://www.ehonproject.org/iwate/e/ehon_car.html

Brown, M. (2011). Waiting for the biblioburro. Berkeley: Tricycle Press.

Ishikawa, T. & Oiwa, K. (2012). 戦後移動図書館活動の検証:千葉県立図書館「ひかり号」調査の概要報告 (A stury of Chiba Prefectural Library’s bookmobile “Hikari” in postwar Japan). Quarterly Journal of the Japan Institution for Library Science, 64(2), 154-163.

Japan Library Association Planning and Survey Committee. (2010). Statistics on libraries in Japan 2010. Tokyo: The Japan Library Association.

Kamakura, S. (2014). 走れ!移動図書館:本でよりそう復興支援 (Mobile libraries, run!: Disaster reconstruction support with books). Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo Publishing.

Nakayama, A. (2006). 日本の移動図書館の現状と課題:西日本の図書館への訪問調査から (Field research on mobile libraries in Western Japan). Journal of Information Society, 11, 47-59.

Shanti. (2015). Mobile library project: Run in Tohoku! Shanti Volunteer Association. Retrieved from http://sva.or.jp/english/

Suemori, F. C. (2013). Remembering the great east Japan earthquake and tsunami, March 2011- “We want them to know they are not alone”. Paper Tiger Blog. Retrieved from

http://www.papertigers.org/wordpress/tag/ibby-congress/

Toppan CSR Report. (2012). Book wagon: Mobile libraries to support the creation of communities. Special Report 1, 6-9.

Cited Children’s Books

Brown, M. (2011). Waiting for Biblioburro.Berkeley: Tricycle Press.

Winter, J. (2010). Biblioburro: A true story from Colombia. New York: Beach Lane Books.

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit archival stream.

- Themes: Junko Sakoi, Yoo Kyung Sung

- Descriptors: Books & Resources, Student Connections, WOW Currents