An Interview with Mary Margaret Mercado: Authentic Picturebook Stories

Interview conducted by Judi Moreillon

Part 3: Authentic Picturebook Stories

This month, I interview Pima County public librarian children's librarian and children's book reviewer Mary Margaret Mercado. Last week, Mary Margaret responded to questions related to publication practices with a closer look at the author, illustrator and translator's cultural knowledge. This week, our conversation centers on the authenticity of the story itself.

Authenticity of Story

Individuals and organizations such as We Need Diverse Books (#WeNeedDiverseBooks) make a concerted effort to draw attention to the number and quality of multicultural, intercultural and global books for young people. In this time of heightened awareness about the need for diverse books, some book review sources are offering free or fee-based, required or optional training for book reviewers. To further ensure accurate reviews, some review sources are increasing their efforts to pair culturally specific books with book reviewers who have cultural insider knowledge.

Mary Margaret and I use these questions to frame our thoughts about culturally authentic stories:

- From whose perspective is the text written?

- Are characters, plot and setting authentic or are stereotypes presented?

- What do the review sources say, and how have cultural "insiders" responded to this text?

Judi: While it may or may not be easy for a cultural insider to spot inaccuracies in literature from their own culture, cultural outsiders likely have a more difficult time doing so. Stereotypes and subtle instances of prejudice and other inaccuracies that harm readers may not be obvious to reviewers who review as cultural outsiders.

What are your strategies for spotting stereotypes in Mexican-themed children's picturebooks? Are there strategies you can share that can help cultural outsiders identify these inaccuracies?

Mary Margaret: Detecting Mexican culture stereotypes involves reading the world of the book through my own cultural experience and also reading the book as if I were a cultural outsider. Closely examining the characters is essential. For a present-day story in which all of the characters are Mexican or of Mexican descent, I would expect there to be representation from all social classes, that gender roles are portrayed appropriately for this century, and that believable characters are naturally taking the roles of family or community members. In short, if there were someone portrayed as a fool or as always doing dumb things in such a book, it wouldn't raise an alarm bell.

However, if in a story with characters from multiple backgrounds, the only brown-skinned character was portrayed as not the brightest crayon in the box, I would immediately intensify my interrogation of the story and look for stereotypes. The names given to characters, the way their physical features are described in print, and their roles in the story are all areas where stereotypes can be hiding in plain view.

For cultural outsiders, which I am when I review a story set in other Latin American or Caribbean countries such as Argentina or Puerto Rico, I recommend asking oneself questions like:

- If there is humor in the story, I ask, "Am I laughing at or laughing with the character?" For example, if a story were set in China with characters speaking in stereotypical mangled English, using such phrases as "no tickee, no washee," I, as well as most readers, would see this as obviously offensive. Yet a story set in Mexico with language like, "Vamos, Skippito--or it is you the Bandito will eato!" is considered acceptable not only to a large sector of the country, but to educators as well. It is surprising how using this type of "humor" to disrespect Spanish speakers and their language can be given a "pass" with no guilt or second-thought whatsoever.

- In addition to characterization and language use, I examine the plot. I ask, "Who has agency and power in this story? Does succeeding or failing, winning or losing, have any connection to a stereotype about which I am aware?" For example, if a story features a main character who represents the dominant culture overcoming obstacles to reach a goal and any character of a different race or ethnicity or a different socio-economic background is solely portrayed in the role of side-kick or supporting cast, I scrutinize the secondary characters more carefully. Is the Native American friend always spouting wise, enigmatic advice? Is the African-American friend always saving the day because of his/her athletic prowess? Is the Mexican-American friend helpful because of his/her street smarts? Is the Asian-American friend the genius computer geek? These types of insidiously "benign" and entrenched stereotypes reflect pigeonholing in real life. It is important to allow characters who are not of the dominant culture to have the full range of experiences, aspirations, talents and expression as any human being would possess in real life.

- Also, the story's setting must be authentic. I especially appreciate stories in which Mexican or Mexican-American children and families are engaged in every day 21st-century activities. While a rural setting with a poor family may be "appropriate" for historical fiction, I often wonder, "Where are the books with middle class Mexican children and families playing video games, using cell phones and flying to the U.S. to visit Disneyland?"

Judi: Do you have advice for the publishing industry with regard to the selection of Mexican or Mexican-American themed picturebooks for publication?

Mary Margaret: There is increasing pressure on the publishing industry to produce high quality books that represent the diverse richness of human experience, and publishers should be more cued to the portrayal of non-dominant culture characters that come across their desks as being honest and authentically well-developed.

Judi: When and why do you consult other published reviews? For a book that is outside your cultural experience, what is your experience of accessing cultural insiders' responses to a book?

Mary Margaret: Before I review any book, regardless of cultural perspective or themes, I go on the Internet and bring up whatever I can find. Many reviews are published in blogs, some can still be found on Amazon, Google Books, and the like regardless of the pre-pub date because of ARCs (advance reader copies). If the name of the reviewer is provided, I do background sleuthing to see if ethnicity/nationality is mentioned. If the book is published outside the U.S., e.g. Barcelona, I try to find images of the author and/or illustrator and to read anything about their cultural credentials in regards to the theme of the book I'm reviewing.

Many times, the reviews rave about a book's diversity, treatment of a global culture theme, the illustrations and more, and I am puzzled. Did the reviewer read the same book I just did? Alternately, I find the book in question has illustrations that are disrespectful or insulting, the featured theme is reinforcing stereotypes, or there is just plain no cultural awareness or expertise on the part of the reviewer. Did the reviewer enjoy said book because it reinforced preconceived or erroneous paradigms that have been made popular in the media or dominant-culture-perceived-reality?

If I find an element that raises my eyebrows and/or hackles, or just resonates off-kilter, and there are no reviews available, I read the publisher's promotional copy. If the book was translated from another language, I can read a little French and Italian because of my Spanish-language fluency. I can also dredge up some of my college German to get the gist of what reviewers in home countries are saying about a specific title.

But reviews from culturally-specific blog sites can alert me to particularly sensitive issues. For Latinx themed books for children, I consult Latinxs in Kids Lit, and for all ages, I consult La Bloga. With further research about theme, author and/or illustrator, I can usually couch my reviews to express any information regarding controversy or insensitivities surrounding a title.

I try to use everything I can get my hands on before I pen my take on a title. I certainly try to incorporate the information gleaned in my review while referring to specific flags triggered by the books' different elements—story, illustration, language and authenticity of cultural representation.

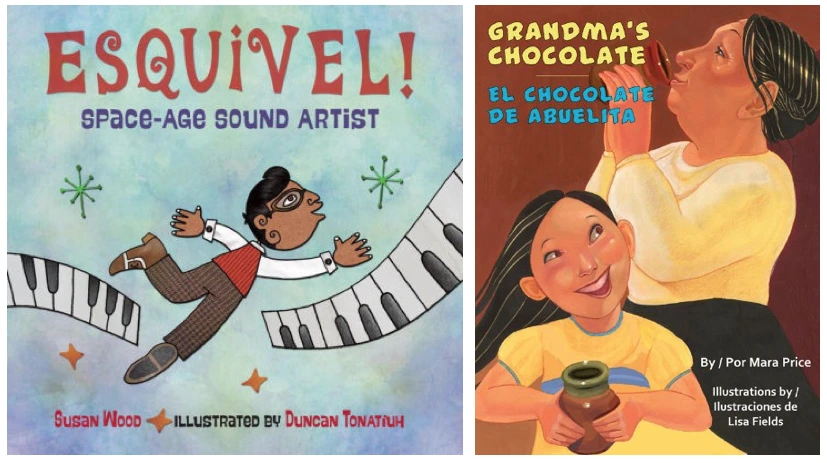

Judi: The book jackets included in this post are two of Mary Margaret's favorite, less well-known titles in terms of authentic storytelling in Mexican and Mexican-American themed picturebooks. Grandma's Chocolate/El chocolate de Abuelita, written by Mara Price and illustrated by Lisa Fields, is bilingual English/Spanish (Piñata Books, 2010). Esquivel! Space-Age Sound Artist, written by Susan Wood and illustrated by Duncan Tonatiuh, is in English only but has a Spanish version, ¡Esquivel! Un artista del sonido de la era especial (Charlesbridge 2016).

Next week, we pick up this interview by exploring ideas related to illustrations in global picturebooks.

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. Check out our two online journals, WOW Review and WOW Stories, and keep up with WOW’s news and events.