by Karen Matis with Charlene Klassen Endrizzi

In our last WOW Currents entry of the month, Charlene and I consider the challenges of supporting science preservice teachers. In past weeks we examined the usefulness of Young Adult picture book biographies to humanize complex content in ELA, history and math classes. We believe middle school learners deserve occasions to study change agents whose lives demonstrate a bridge between complex school content and purposeful use of this content in everyday lives.

My middle school students would express how reading a science or math textbook felt like being immersed in a new language. Science and math textbooks differ from those in social studies and ELA classrooms. Math and science teachers need to incorporate strategies that focus on using the language of their disciplines to communicate ideas. This presents new challenges for students, too. New vocabulary is introduced. Familiar words become unfamiliar in the discipline’s context. Abstract concepts and lexical density disrupt reading pacing, creating an “overload of content information” (Johnson, 2013).

This month’s focus on disciplinary literacy stems from the need to prepare pre-service educators for students who need different strategies and skills for understanding complex texts. In the science classroom, “generic literacy skills and strategies may be inappropriate, and thus the current challenge is for content teachers to identify which strategies have merit” (Johnson, 2013). Batchelor (2017) found that students’ curiosity and interest was positively stimulated when using picture books as an introduction to learning about ancient civilizations. Could the success in the her classroom be replicated in science by introducing nonfiction picture book biographies?

We continue to see the usefulness of using picture book biographies to introduce change agents and related concepts within disciplines. The language in biographies is easier for students to understand. Accompanying illustrations set a productive tone for learning, help to clarify complex concepts, and in general create a “story” that’s easier to follow. In the science classroom, these productive elements represent the merit Johnson (2013) seeks.

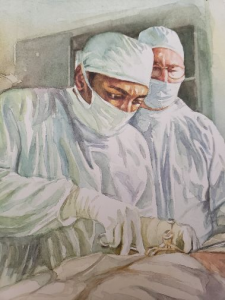

Marina, a neuroscience major, centered her first Learning Invitation on engaging students in an exploration of the heart’s blood circulation pathway. Using Hooks’ biography Tiny Stitches: The Life of Medical Pioneer Vivien Thomas, Marina began her invitation by featuring the heart’s functions, using visual literacy strategies and historical connections. Though the history of Viven Thomas is sprinkled with racism and resistance, his resilience persevered; Thomas developed a surgical procedure for “blue babies” to repair specific heart defects. His determination to pioneer new procedures provided hope to parents of these special babies.

Classified as a janitor before he advocated for the title of “researcher”, Thomas studied the circulation of blood in healthy hearts and noted four defects that caused oxygen-poor blood in some babies. Assisting Dr. Blalock, cardiac surgeon, Thomas “coached” Blalock performing over 150 of these surgical procedures. Marina found how Thomas’ biography, filled with science-rich vocabulary (artery, ventricle, atrium), offered a relevant context that aided students’ understanding. The National Endowment for Humanities funded Partners of the Heart, a video documentary of Thomas’ hidden rise to notoriety.

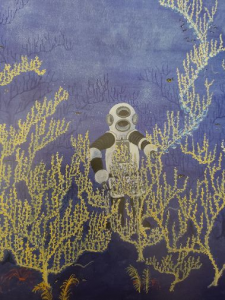

A memorable experience I cherish is snorkeling in Hawaii. Hidden treasures under the water’s surface introduced me to a colorful world not observable from a sandy beach. Life in the Ocean: The Story of Oceanographer Sylvia Earle (Nivola, 2012) introduces plant and animal life underwater and the need to protect their habitat. Sylvia found a “home” in the undersea world she investigated. One topic for physics classrooms (sound wavelengths) is explored through Sylvia’s experience hearing whales sing. Her descriptions of the whales’ behaviors, rollicking, frolicking and dancing, stem from her close observations.

As a Language Arts teacher, I noticed Nivola’s use of figurative language to describe Sylvia’s underwater experiences. Her observations of bioluminescent creatures at 3,000 feet below the water’s surface is recounted like “diving into a galaxy”. Creating a visual for the reader, Nivola compares Sylvia’s aqua suit to one “that looked like a space suit”. Exploring coral reefs, the author describes Sylvia’s experience, “There weren”t stars visible. . . but there were bioluminescent creatures flashing with their blue fire”. Nivola’s expressive language encourages learners to visualize underwater phenomena.

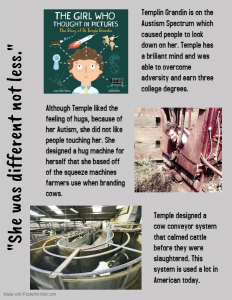

Preservice teacher Ella was fascinated by the biography picture book The Girl Who Thought in Pictures: The Story of Dr. Temple Grandin (Mosca). Capturing the diversity of this amazing scientist, Ella created a visual for her learners to meet Grandin and learn about accommodations that inspire creativity and industry. She encouraged students struggling with science to explore Grandin’s courage, “All students have things they need to overcome throughout their life . . . this book will help students see that even though Grandin has Autism, she still earned three college degrees.” Mosca reinforces Ella’s thoughts suggesting, “Being DIFFERENT might just be what makes you so NEAT!”

Grandin’s website provides further glimpses into her personal struggles with algebra. Math major Ella seizes on Grandin’s cross-curricular connection by discussing how “Science goes hand-in-hand with math.” Grandin admits her life would have taken a different course had it not been for her own constancy in study and the assistance of academic tutors.

Environmental studies often focus on water quality and engage students in collecting water samples from nearby creeks for testing. Introducing Tantoh Nforba, better known as Farmer, provides students with foundational insight into areas where clean water is a scarce commodity. I Am Farmer: Growing an Environmental Movement in Cameroon (Paul & Paul, 2019) follows Tantoh’s life as a young boy with a secret garden, who brought hope in the form of clean water to communities in his native Cameroon.

As a young boy, Farmer was curious. He questions his ma kfu (grandmother) about gardening. At school, he asks so many questions his teacher becomes frustrated. Still, Farmer nurtures his interest in soil and planting, keeping a journal of his processes, observations, and discoveries. Overcoming taunts from his peers who believed farming was synonymous with a life of poverty, Farmer’s resiliency and interests were instrumental in his success. Introducing Farmer to students in the science classroom invites students to learn about watersheds and clean water as well as the importance of the scientific process of observation and documentation.

Charlene’s disciplinary literacy course with English, history, math and science majors continues to undergo changes. Over five years we discovered patterns of English and history preservice teachers being more willing to consider the usefulness of disciplinary literacy and the exploration of relevant, relatable young adult fiction and non-fiction texts. Math and science majors will continue to challenge us. We maintain the need for biographies featuring diverse, inspirational change agents, offering points of connection between complex content and professional lives beyond high school. We hope secondary preservice teachers and classroom teachers continue to investigate resources such as picture book biographies that explore hidden legends and stories. In our current era filled with health and social justice uncertainties, we advocate for the place of culturally responsive instruction featuring inspirational global citizens like Vivian Thomas, Zaha Hadid, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Arturo Schomburg.

References

Batchelor, Katherine E. (2016). Around the world in 80 picture books: Teaching ancient civilizations through text sets. Middle School Journal, 48:1, 13-26. DOI: 10.1080/00940771.2017.1243922

Johnson, H. (2013). Letter from the editor: What’s literacy got to do with science and math? School Science and Mathematics, 113(3), 107-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssm.12011

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit its archival stream.

Since all students do not learn the same way, creative strategies must be explored to find a way to feed each individual’s unique style of learning. The strategy discussed in this article is a reasonable and useable approach and should be explored by educators. If you teach a child “how-to-learn” at an early age, that process will be repeated in every challenge presented, regardless of the subject matter. The destination is a given, but how the student arrives is determined by what road map he/she uses.