By Holly Johnson, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH

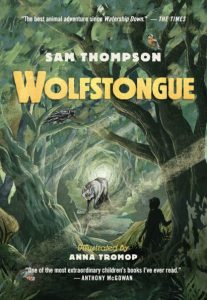

There are many great books for young people available, and summertime is a great time to take advantage of the books we might have set aside hoping to get to them. Within the numerous books we might read, every now and then there is one that not only brings us pleasure but can have us thinking deeply about the state of the cosmos. Wolfstongue (2021) by Sam Thompson is one such book. I want to take nothing away from any number of books that might also have readers thinking philosophically about the world, but this book awed me in its thoughtfulness and its cosmopolitan way of envisioning the relationship between humans and nonhuman animals, and the role language plays in our often-hierarchical stance toward other species and the power differential displayed within those relationships. In the following paragraphs, I want to share some of the instances that had me contemplating and appreciating the marvels of this book.

There are many great books for young people available, and summertime is a great time to take advantage of the books we might have set aside hoping to get to them. Within the numerous books we might read, every now and then there is one that not only brings us pleasure but can have us thinking deeply about the state of the cosmos. Wolfstongue (2021) by Sam Thompson is one such book. I want to take nothing away from any number of books that might also have readers thinking philosophically about the world, but this book awed me in its thoughtfulness and its cosmopolitan way of envisioning the relationship between humans and nonhuman animals, and the role language plays in our often-hierarchical stance toward other species and the power differential displayed within those relationships. In the following paragraphs, I want to share some of the instances that had me contemplating and appreciating the marvels of this book.

A wonderful story about Silas, a young boy who has difficulty with speaking, Wolfstongue features language usage and the power of language to harm others as well as undermine a person’s own value. Silas is bullied at school because he has difficulty speaking. At home, his parents demonstrate care and anxiety over Silas’ inability to express himself fully. But when Silas encounters a wolf on his way home from school, his situation changes. As Silas learns about Isengrim and Hersent, a wolf family, he finds that when he is with them, he has begun to speak more clearly. And it is through his relationship with the wolves that Silas eventually becomes a “Wolftongue,” one who speaks for the wolves. He uses this ability when Isengrim’s and Hersent’s three cubs are kidnapped by the foxes and taken to the city of Earth—the foxes elaborate underground den modeled after the human world.

The issue of power becomes quickly apparent when the boys at school harass Silas, but it is the situation within the forest that will have readers thinking about how language works to the detriment of one species over another. Foxes have power over wolves, and replicating their understanding of the human world, the foxes enslaved the wolves to do their bidding. It was by naming the wolves that this situation occurred. To name something or someone can be one way to gain control or power, and as Isengrim, the lion, explains about Reynard, the ruler of the foxes, “He gave me my name…before that, I could have ignored him. Or I could have ended him with one blow of my paw. But after he gave me a name, I had to listen.” (p.34) Thinking about how naming or identifying something, labeling it, can create a power dynamic is a concept especially critical for young people to understand. Along with the concept of power and language is how the appropriation of language has been used for determining class or social status. How does the use of particular words and language garner power for the user? How has such appropriation changed a language user and that person’s relationship with others?

And then there is the issue of rules. “The foxes get their power from their rules…” (p.51) And determining the rules—both socially and linguistically—has often determined the power dynamic between humans and also between humans and nonhuman animals. Every day humans measure their power over other elements of the cosmos, by suggesting their use of language is what creates our dominance over the earth and everything in it. Perhaps the use of words and that dominance needs to be re-evaluated. At one instance, Isengrim is explaining how the wolves had no need for words noting, “so that we could live as wolves ought to live. Free from words.” (p.81) Given how language has proven so detrimental to the wolves’ welfare, readers might begin to think about how sometimes silence, and a lack of definition, can be empowering.

Further into the book, a renegade fox who bands with Silas and the wolves explains how things are not going well for Earth, the foxes’ city, now that there are no more wolves remaining to do labor. In this passage, readers find out about how the city was meant to “bring a better life for every fox” but now the foxes must do for themselves, and a class system has been established (p. 93). Thinking about history and how nations and civilizations have been built on inequitable labor is another aspect for young people to explore through Wolfstongue.

Later on, the company of a young boy, one fox, two wolves and two other nonhuman animals who are on a mission to rescue the young wolf cubs, they encounter caged chickens and readers are quickly reminded of how the food we eat is often “farmed” in small cages and enclosures from birth to butchery.

There are other instances through the book that we have readers revisiting their world view and the “norm” of language usage, social status, and human and nonhuman animal relationships. Thinking more about the way we encounter the world and our interactions within it is one of the strengths of Wolfstongue, but there are many more. A story with the potential to become a classic, this story not only is a great adventure, but a treatise on how we might better think about our place in the world.

WOW Currents is a space to talk about forward-thinking trends in global children’s and adolescent literature and how we use that literature with students. “Currents” is a play on words for trends and timeliness and the way we talk about social media. We encourage you to participate by leaving comments and sharing this post with your peers. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit its archival stream.

- Themes: Holly Johnson, Sam Thompson, Wolfstongue

- Descriptors: Books & Resources, WOW Currents