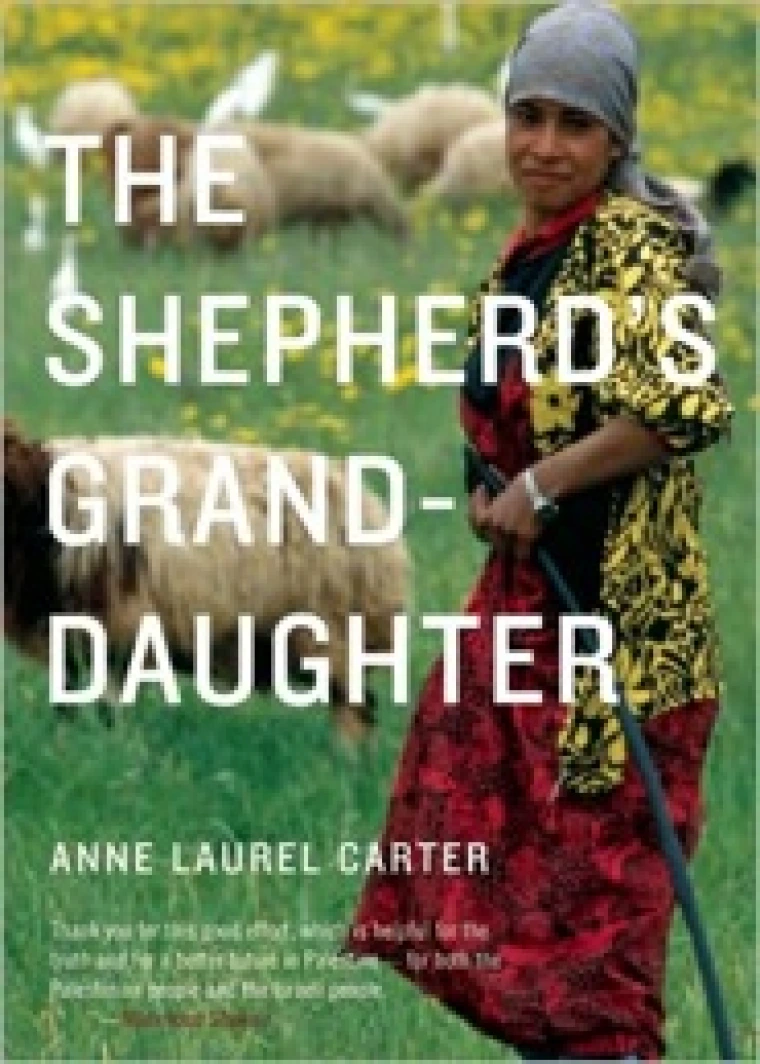

The Shepherd’s Granddaughter

Amani longs to be a shepherd like her beloved grandfather Sido, who has tended his flock for generations, grazing sheep on their family’s homestead near Hebron. Amani loves Sido’s many stories, especially one about a secret meadow called the Firdoos. But as outside forces begin to encroach upon this hotly contested land, Amani struggles to find suitable grazing for her family’s now-starving herd. While her father and brother take a more militant stance against the intruding forces, Amani and her new American friend Jonathan accidentally stumble upon the Firdoos and begin to realize there is more to life than fighting over these disputed regions. Amani learns a difficult lesson about just what it will take to live in harmony with those who threaten her family’s way of life. Take a closer look at The Shepherd's Granddaughter as examined in WOW Review.