By Holly Johnson, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH

Like most people, when I read I have images playing my head, almost like a movie. I am traveling! But to get that movie and to take that journey, I need some prior knowledge about the setting of the story along with other details that bring the text to life. If I have a sense of the setting I don’t attend to the description as much as when I need to build the picture in my head from scratch. If I have been to a place, it serves as a handy backdrop to the piece of literature I am reading. When I haven’t been there, I need help. Of course, most of us do not have the extensive travel experience we would need (or like) to feel comfortable reading in this way. But travel is handy. It was also my passion when I was younger, and so I find that my experience of different places I have been are useful for my reading of international literature—on two accounts.

First, I like reading about where I have been. The reading is enriched when I can picture it. I pull the images from my memory to help envision the world to which the author has led me. Secondly, the reading enriches my experience of the places I have traveled. It’s also great to find books to read about a place—whether fiction or informational—when planning to travel in it. Some fun texts for cities across the globe are the Miroslav Sasek series such as This is London and This is Rome. These books were written in the 1960s and 1970s, but have “this is today” excerpts that help students see how cities change over time.

First, I like reading about where I have been. The reading is enriched when I can picture it. I pull the images from my memory to help envision the world to which the author has led me. Secondly, the reading enriches my experience of the places I have traveled. It’s also great to find books to read about a place—whether fiction or informational—when planning to travel in it. Some fun texts for cities across the globe are the Miroslav Sasek series such as This is London and This is Rome. These books were written in the 1960s and 1970s, but have “this is today” excerpts that help students see how cities change over time.

Continue reading

If you ask me what I came to do in the world, I, an artist, will answer you: I came here to live out loud. — Emile Zola

If you ask me what I came to do in the world, I, an artist, will answer you: I came here to live out loud. — Emile Zola I am on a hunt. I am searching for the variety of ways international literature might be conceptualized by teacher educators, teachers, and teacher candidates. I am also interested in the ways in which they might address and differentiate between international and multicultural literature as well as how they perceive various other terms that might be used for literature that, well, transcends its native borders. I became interested in such a venture because it seemed as though as much as I discussed what I suggested was the difference between, say, “international” and “multicultural” literature, the terms and their nuances seldom transferred to my students. Was I not trying hard enough? Was I being too esoteric? Needless to say, I found the phenomenon intriguing, and so thought I would broach the topic via WOW Currents.

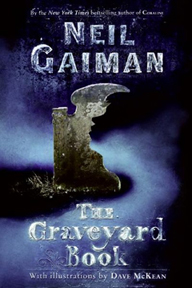

I am on a hunt. I am searching for the variety of ways international literature might be conceptualized by teacher educators, teachers, and teacher candidates. I am also interested in the ways in which they might address and differentiate between international and multicultural literature as well as how they perceive various other terms that might be used for literature that, well, transcends its native borders. I became interested in such a venture because it seemed as though as much as I discussed what I suggested was the difference between, say, “international” and “multicultural” literature, the terms and their nuances seldom transferred to my students. Was I not trying hard enough? Was I being too esoteric? Needless to say, I found the phenomenon intriguing, and so thought I would broach the topic via WOW Currents. This is the fourth of a planned four-part interview with Nick Glass, member of the 2009 Newbery Committee, conducted electronically by Judi Moreillon.

This is the fourth of a planned four-part interview with Nick Glass, member of the 2009 Newbery Committee, conducted electronically by Judi Moreillon. This is the third of a planned four-part interview with Nick Glass, member of the 2009 Newbery Committee, conducted electronically by Judi Moreillon. Readers may refer to

This is the third of a planned four-part interview with Nick Glass, member of the 2009 Newbery Committee, conducted electronically by Judi Moreillon. Readers may refer to

Sometimes when colleagues who are insiders to a culture talk about small details of inaccuracies in particular children’s books, like the kimono being folded wrong or the atypical hairstyle of a character, my immediate response is to think, “Okay, I can see your point but aren’t you being a bit picky?” I want to point out that the bigger themes in the book are more significant and that differences exist within a culture, so that what seems like an error to one insider is considered appropriate by another. Even cultural insiders sometimes get these details wrong. I reminded of Yoo Kyung Sung’s conversation with a Korean American author whose young adult novels have won major awards, but who uses Korean terms in how the brother and sister address each other that are incorrect and that infer a feminization of the brother that is not intended. The author’s reply was that Koreans always point that out, and that she didn’t realize the terms were incorrect—they were the ones used in her family who had been in the U.S. for several generations.

Sometimes when colleagues who are insiders to a culture talk about small details of inaccuracies in particular children’s books, like the kimono being folded wrong or the atypical hairstyle of a character, my immediate response is to think, “Okay, I can see your point but aren’t you being a bit picky?” I want to point out that the bigger themes in the book are more significant and that differences exist within a culture, so that what seems like an error to one insider is considered appropriate by another. Even cultural insiders sometimes get these details wrong. I reminded of Yoo Kyung Sung’s conversation with a Korean American author whose young adult novels have won major awards, but who uses Korean terms in how the brother and sister address each other that are incorrect and that infer a feminization of the brother that is not intended. The author’s reply was that Koreans always point that out, and that she didn’t realize the terms were incorrect—they were the ones used in her family who had been in the U.S. for several generations. The need for book reviewers who are either cultural insiders or who consult with cultural insiders in writing their reviews has become increasingly apparent to me. Seemi Aziz Raina and Yoo Kyung Sung in their research on the representations of Muslims and Korean Americans in children’s literature have identified many subtle issues that would be difficult to identify by someone who does not have some kind of insider knowledge. They have also found that the recency of that insider knowledge is critical.

The need for book reviewers who are either cultural insiders or who consult with cultural insiders in writing their reviews has become increasingly apparent to me. Seemi Aziz Raina and Yoo Kyung Sung in their research on the representations of Muslims and Korean Americans in children’s literature have identified many subtle issues that would be difficult to identify by someone who does not have some kind of insider knowledge. They have also found that the recency of that insider knowledge is critical.