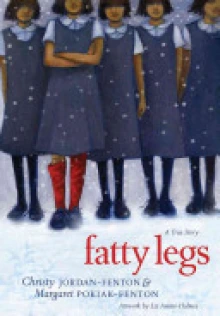

Beginning with Fatty Legs: A True Story, these two books comprise the story of young Margaret Pokiak growing up in the high Arctic during the early twentieth century. At eight she wants to go to school and learn how to read in English. The problem is that missionary Christians run the only school teaching English. The nuns look and act differently from most of Arctic nomads and the school is far from where they live. Despite the long trip, the missionaries come looking for the children and force them to attend their school. Margaret has an older sister who has been to this school but her sister’s stories of the terrors and pressures of the school are ignored by Margaret and she convinces her father to send her there.

Margaret soon learns that her free spirit and love for learning are challenged at every turn in her new life. Her encounters with a teacher known as the Raven, a black-cloaked nun with a hooked nose and bony fingers that resemble claws, immediately puts Raven on the defensive. The nun, in turn, immediately dislikes the strong-willed Margaret. Raven humiliates her at every turn and finds insignificant reasons to poke fun at Margaret. Raven gives her red stockings when she has a perfectly fine pair of grays (a school color), making Margaret the laughingstock of the entire school, and she burns the stockings. Thus, the battle of wills continues. Sister MacQuillan is the opposite of Raven and steps in when life is unbearable for Margaret. There is no learning to read at the beginning of the school year, instead the students are taught to clean themselves and their surroundings. They are forced to work in the fields and throw away buckets of refuse. These tasks are new and distasteful to the students from the Arctic, but they have to do it anyways because their families are far away. The nuns also intercept the letters that students write home to ensure that nothing negative about the school is sent home. Margaret and others are prisoners in the school and miss their free lifestyle. Due to an especially strong winter, the students cannot visit their families at the end of the year and are forced to endure another year within the suffocating school walls. Margaret vows never to come back once she goes home.

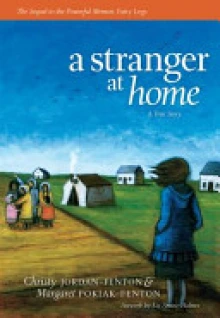

A Stranger At Home: A True Story is a sequel and continues the childhood memories of Margaret Pokiak. This story begins at the end of the two grueling years when Margaret was forced to stay at the boarding school and not able to see her family. She endures all kinds of humiliation at the hands of the nuns but learns a lot more than reading in English. At ten she finally travels to be reunited with her family in the Arctic; she can hardly contain her anticipation. She finds that two years have altered her beyond recognition, and she has forgotten the things that were second nature to her including her own language.

As she comes ashore, Margaret spots her family, but her mother refuses to recognize her and repeats that Margaret is, "Not my girl." It is at this point that she realizes how much she has changed not only outwardly but also psychologically. She resides in a “third space” marked as an outsider by her own people. She has forgotten not only her language but also the stories of her people and her ancestors. She can't even stomach the food her mother prepares which she used to love and dreamed of when she was a prisoner in the boarding school.

As she is so different from her former self, she starts referring to herself as two separate people: Olemaun her real name as her older self and Margaret as her new self with new ways. “I said grace silently in my head six times, once for each of them and once for Olemaun, because Margaret knew about kneeling and bowing and praying, but Olemaun did not” (p. 43). Margaret tries to force her newly learned mandatory religion (Christianity) on her family because she wants to protect them from Hell. When she insists on reading the Bible and praying before eating, her father reacts angrily and says, “I have read the Bible…just stories. That’s all I found in it, so you can leave that God business at the school” (p. 43). She does not seem to be able to move away from that influence. Other people from her tribe stay away from her for fear she will adversely influence their children with her foreign ways and religion. Her friends are not allowed to be with her. Her experiences of ostracism from her own people are so great that she feels one with a “large, dark-skinned man” (p. 47) who comes to sell pellets and is referred to as the Devil “Du-bil-ak” because of his physical persona.

After many emotional, psychological, and physical struggles she finally settles into her old life and relearns a lot that she has forgotten, especially her language. Her father is a gentle presence who guides her through this unlearning and relearning process. Her mother later accepts her differences and supports her. Her interactions with her younger siblings and family are carefully developed, but there is no mention of her older sister whose influence made her want to attend the school in the first place

In the sequel, Margaret once again needs to go back to the abhorred school as it the only choice for education for her younger siblings and she is the one who can protect them as they are now being forced to attend by the nuns. The author’s note explains that Margaret did go to the school and provided the necessary scaffolding to her sisters so that they did not forget their language, stories and ways.

The author, Margaret, is the real protagonist of the novels and it is her life events that she and Christy, her daughter-in-law, use to inform the writing of these books. Christy lives in British Columbia. The first book is spontaneous and the truth of the story weaves together with the storytelling but the writing is not well developed. The second novel is written better than the first one and keeps the audience captivated. There are actual photographs from ‘Olemaun’s Scrapbook’ that lend authenticity to the anecdotes and stories. There are photographs added as sidebars within the actual narratives that explain a term or direct the reader to the photographs at the end of the books. The author’s notes lend clarity and credibility to both narratives. The art by Liz Amini-Holmes, is beautiful with emphasis on deep vibrant colors. The expressions of the characters are captured well. Even though the illustrator is from San Francisco she seems to cross the cultural boundaries on wings of imagination by evoking an authentic cultural atmosphere and facial features. Having lived in Catholic convent boarding school when I was growing up in Pakistan, I saw many similarities with the incidents mentioned in this story specifically the letter writing and censorship and differences in treatment between Christians and Muslims. As Muslim girls, we were made to scrub church floors and undertake other menial jobs for nuns and the Christian girls while our Christian counterparts were protected and favored.

This story is one of many about forced journeys and ‘education’ by missionary Christians within the regions that the Western nations colonized and occupied. It was especially difficult for indigenous peoples from regions settled by western societies, such as Australia and the United States. First Nation people and American Indians have many books capturing these events with similar thematic threads, such as: The Indian School (Gloria Whelan, 1996), Indian School: Teaching the White Man's Way (Michael L. Cooper, 1999), and Boarding School Seasons American 1900-1940 (Brenda J. Child, 1998).

Seemi Aziz, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK

WOW Review, Volume IV, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/review/reviewiv2.

Reference

Seemi Aziz. “Book Review: Fatty Legs: A True Story”. WOW Review, vol. IV, no. 2, Worlds of Words: Center for Global Literacies and Literatures (University of Arizona), Jan. 2012.