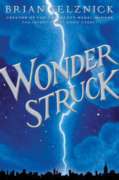

Wonderstruck

Written by Brian Selznick

Scholastic, 2011, 608 pp.

ISBN: 978-0545027892

After the sudden death of his mother, Ben has to live with his well-intentioned, financially struggling aunt and uncle, sharing a room with his cousin, Robby, who delights in bullying him. Desperate to find out more about his father whom he has never known, Ben is drawn back one night to the cottage where he and his mother used to live and, in the middle of a lightening storm, finds a clue about his father that persuades him to run away to New York City. Fifty years earlier, Rose feels stifled by her life with her father in Hoboken, New Jersey, and is frantically trying to connect with her film star mother whose life she tenderly documents in a scrapbook.

Caldecott medal-winning author, Brian Selznick, intertwines two lives—Ben’s told in words and Rose’s in drawings. Both are searching for love and belonging. Both collect objects and facts that connect them to the world. Both are deaf, but have come to deafness in different ways. Readers certainly empathize with Ben’s and Rose’s struggles, but they also become acquainted with their obvious strengths. Selznick reveals that deafness itself can be an asset, for example, by having Ben use his deaf ear to tune out his cousin’s annoying CB radio. In the field of Disability Studies, Swain and French (2000) have contrasted the medical model of disability (as an abnormality to be cured, a personal tragedy, a charity case, etc.) with the affirmation model where disability has a positive identity for the individual or the group. Ben and Rose clearly represent the affirmation point-of-view.

Although more than 600 pages long, over 460 pages convey the story through illustrations that engage younger and older readers alike and support individuals who experience reading difficulties. With compassionate prose and spellbinding graphite drawings that transport us from Gunflint Lake, Minnesota, in 1977, to Hoboken, New Jersey, in 1927, we are swept up in a mesmerizing journey through movie theaters, book stores, the American Museum of Natural History and the Queens Museum of Art in New York City. Selznick is masterful at varying the tempo of the narrative. At times, we share Ben and Rose’s panic as they search for family members; at other moments we pause to absorb the intricate details of the “Cabinets of Wonders” and the “Panorama.” When Ben starts to use fingerspelling toward the end of the storyline, the reader must slow down to work out what he is saying, and to fully appreciate his new self-empowerment.

In the Acknowledgements, readers learn that Selznick, whose brother was born deaf in one ear like Ben, carefully researched Deaf culture as well as the transition from silent films—where deaf and hearing audiences could enjoy the world of cinema together—to the “talkies” that, by their very nature, excluded deaf film goers. Selznick’s story shatters the monolithic term “the deaf” by including two very different portrayals of deafness where the individuals use a variety of means to communicate, including ASL, fingerspelling, writing, lip-reading as well as some speech. The author’s attention to detail and socio-historical accuracy, ground this fantastic story in reality. A discussion and exploration guide for educators is available.

Scholastic provides Intriguing essays by scholars on Deaf culture, silent to sound film, the American Museum of Natural History, etc., as well as an interactive game to learn how to fingerspell.

Educators should acquaint themselves with the history and diversities within Deaf culture in the United States and also with the disturbing ignorance and prejudice towards deafness within the hearing world. The documentary, Through Deaf Eyes (Diane Garey and Lawrence Hott, 2007), and Myron Uhlberg’s memoir about growing up as the hearing son of deaf parents, Hands of My Father (2009), influenced Selznick’s writing and are thought-provoking resources for educators. To extend understanding about deaf experiences with young readers using exquisite storytelling and illustration, Wonderstruck can be paired with Andrea Stenn Stryer’s Kami and the Yaks (2007) and Myron Uhlberg’s The Printer (2003) and Dad, Jackie, and Me (2006). For readers in the secondary grades, Anthony John’s Five Flavors of Dumb (2010) challenges assumptions about deafness and disability in a sassy and sensitive way. Educators will undoubtedly want to heighten appreciation for Selznick’s craft as an author illustrator by connecting readers to his other major works. The Invention of Hugo Cabret (2007) shares common themes with Wonderstruck—films, orphans, survival and self-discovery— and are both complemented by fine graphite drawings. In both novels Selznick provides a refreshingly affirmative understanding of disability experiences.

Swain, J., & Frenchm S. (2000). Towards an Affirmation Model of Disability. Disability and Society, Vol 15.4, pp. 569–82.

Chloë Hughes, Western Oregon University, Monmouth, OR

WOW Review, Volume V, Issue 4 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/review/v-4/