Journey on the Silk Road: Creating a Google Lit Trip

By Sue Corbin

In an essay about a musical piece based on the Silk Road, cellist Yo-Yo Ma wrote:

For me, the Silk Road has always been fundamentally a story about people, and how their lives were enriched and transformed through meeting other people who were at fist strangers.

Our collaborative team consisted of one reading teacher (Sue Corbin), one English teacher (John Koppitch), two social studies teachers (Maureen Carroll and Jessica O-Brien), a science teacher (Paul Repasy) and a math teacher (Jennifer Weisbarth), all in seventh grade classrooms at Shaker Heights Middle School. In our group meetings, we talked a lot about how integral traditional literature is to an understanding of cultures, and how such tales could be foundation pieces for learning across the curriculum. In seventh grade, students study the Silk Road nearly all year in social studies, so this was a natural theme to incorporate into every core subject. We met weekly to choose stories we thought students would relate to, and to plan lessons that built on their growing knowledge of the Silk Road.

We wanted to create a product that would be interactive, high tech, global in scope, and literature-based, and found exactly what we were looking for in Google Lit Trips. These trips are multimedia journeys through fiction and nonfiction literature that allow students to experience a story as if through a prism of information. A Lit Trip uses Google Earth to navigate the places in a book, look at them from a myriad of perspectives, and consider the interactions between the places and the characters and plot of a story.

Jerome Burg developed the idea and created the first Lit Trips. He wanted students to be able to “see” the places they were reading about without having to leave home. The approach is a brilliant way to help students make connections between the text and the world.

Most Lit Trips involve stopping along a journey by zooming in on a particular place using Google Earth protocols. Students can read and answer questions at each site and reflect on the book they are reading. There are links to websites about the place, embedded photographs and videos showing particular aspects that are in the book, and different ways to view the landscape. All of the possibilities that are available on Google Earth are also available on a Lit Trip, so that students can check the weather or see borders and roads. They can virtually fly from place to place along the route, following the numbered stops, in or out of sequence.

We knew that our middle school students were interested in finding places on Google Earth from watching them during their spare time on computers. They are digital natives who are usually more motivated to read from a screen than from a book. They are diverse learners who need to participate in multisensory lessons that appeal to their visual, auditory, and kinesthetic learning styles.

One of the recurring themes in the seventh-grade World History curriculum is the history and culture of the Silk Road, so we chose this as a natural basis for a Lit Trip. We wanted our trip to show historical and current information about the places, people, inventions, knowledge, art, literature, and cultures that made the Silk Road such an important route. We wanted students to better understand how the past influences the present and the future, and to see how human experiences from faraway places and times can affect people everywhere.

We had some difficulty determining an appropriate book that could provide authenticity of the Silk Road’s history, and, at the same time, be appealing and accessible to all of our students. It was crucial to find a “reader friendly” text that could be read by struggling readers and be challenging for the more advanced readers in our classrooms. We found that while there are many historical fiction books about places along the Silk Road for adolescents, many of them provide perspectives that are uniquely Western. So, we thought of using traditional literature to offer clues about the cultures, knowledge, and beliefs of the ancient Asian and Middle Eastern inhabitants along the road.

We were concerned about the use of traditional literature with seventh-grade students in that they might view these stories as “baby” stories, especially in a picture book format. However, we believe that traditional literature is rich with information, and that these stories beg to be read by readers of all ages. Jane Yolen (1981) called the dissemination of folk tales “mouth to mouth resuscitation” (p. 22). In Touch Magic, she says,

Folklore is, of course, imperfect history because it is history constantly transforming and being transformed, putting on, chameleonlike, the colors of its background. But while it is imperfect history, it is the perfect guidebook to the human psyche; it leads us to the understanding of the deepest longings and most daring visions of humankind. (p. 50)

What better reason to use ancient tales as the foundation for the Silk Road project?

Our literature search led us to Cherry Gilchrist’s (1999) Stories from the Silk Road, illustrated by Nilesh Mistry. In her introduction, Gilchrist provides background about the trade route that linked the East to the West, possibly even into Western Europe. One of the more important points that she makes is that the road “was also an important route for the exchange of ideas. Knowledge of astronomy, medicine and science passed along it, and religions were spread via it…Art too changed and developed because of this exchange” (p. 6). The stories themselves are simply told and can be explored on many levels. We felt that this was a “just right” book for our purpose of using global literature for a cross-curricular study that would explore the interconnectedness of people across time and place.

Gilchrist uses the voice of the “Spirit of the Silk Road” to guide readers from Changan to Samarkand, listening in on storytellers as they relate the mysteries of silk, mischievous monkeys, demons and dragons, and the foibles of human nature. Each story has a two-page introduction to the trading stop told in a “you are there” format that draws readers into the city or town. Mistry’s masterful use of border illustrations reveals the presence of the guiding Spirit as he shows the splendors of the trading stops. Readers can spend a long time looking for clues about the people, places, and stories in the colorful drawings. A common thread within the images for each story is a caravan of traders as they work their ways across mountains, rivers, and deserts by camel and on foot.

We also chose a companion nonfiction picture book, The Silk Route: 7,000 Miles of History by John S. Major and illustrated by Stephen Fieser. This book served as a quick review of places and topics for students who had already completed studies about the Silk Road in their social studies classes.

We wanted to engage students as much as possible so that they could contribute to the Lit Trip with their written questions about the stories, information and websites on the Internet, and content area activities that could be included on the stops. An excellent way to keep students actively engaged is to use learning stations that allow students to explore in their own ways. There was no time limit for the length of a visit to a learning station, but all students were expected to complete all stations by the end of the unit.

Our learning stations included:

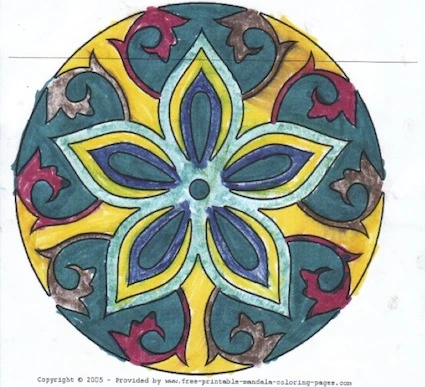

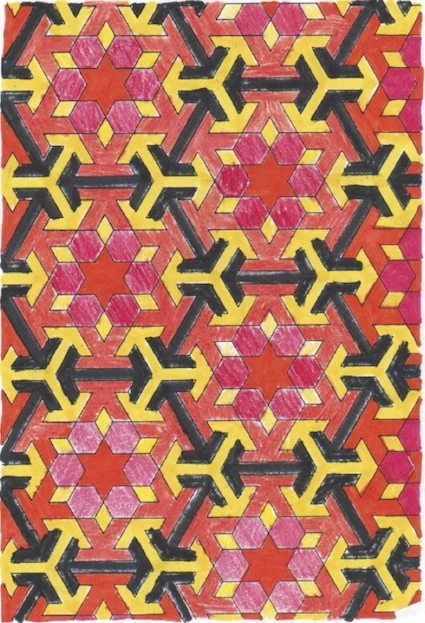

- Tiles and mosaics (exploring mathematical geometric patterns through reading articles, examining illustrations, and coloring copies of mosaics)

- Confessional or Diary Entry (planning and composing a confessional or diary entry of a traveler along the Silk Road)

- Music of the Silk Road (listening to samples of music from the Silk Road on selected internet sites)

- Time line (creating a time line banner in words and pictures about the history of the Silk Road)

- Mapping (locating and coloring in maps depicting stops along the Silk Road)

- Folk Tales (reading Stories from the Silk Road by Cherry Gilchrist individually or in pairs or small groups)

- Web quests on the Silk Road and Stanford University virtual lab and on Marco Polo (students work at computers to explore websites based on Silk Road adventures of travelers, particularly Marco Polo)

- Video of Genghis Khan (students watch an internet video of Genghis Khan and take notes on his biography and contributions to the Silk Road)

- Artifact Walk (students explore illustrated posters of objects found along the Silk Road, predict and study their uses)

- Children’s Book (students write a children’s picture book about a traveler along the Silk Road)

- Silk Worm Lab (students view actual silk worms under microscopes, read articles about silk worm biology and life cycle, and take lab notes; an optional addition is the opportunity to write a haiku about silk worms)

- Silk Road Math (students work on word problems based on length, distance, and time for a Silk Road traveler)

The stations were intentionally designed to invite students into ancient cultures by engaging them in literature, music, art, math, science, and history. We wanted students to attempt to transform themselves and enter the ancient or current environment of the Silk Road, to use the four major academic content areas to submerge themselves into the Silk Road cultures, and to think of themselves as citizens from this particular geography. Materials needed for the learning stations were:

- Computers (about 20)

- Microscopes

- Silk worms (containers)

- Large pieces of paper and colored pencils

- Copies of Stories from the Silk Road and The Silk Route: 7,000 Miles of History

- Calculators

- Handouts

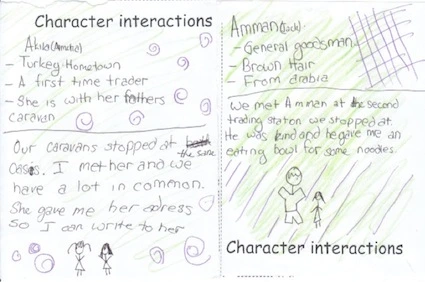

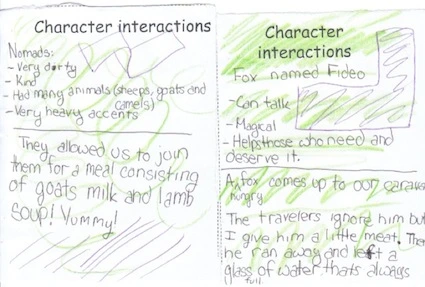

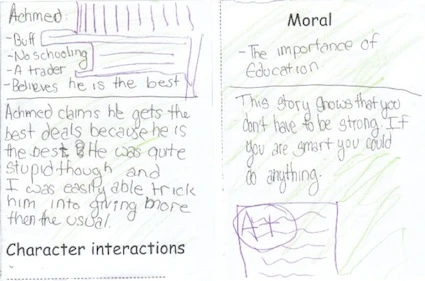

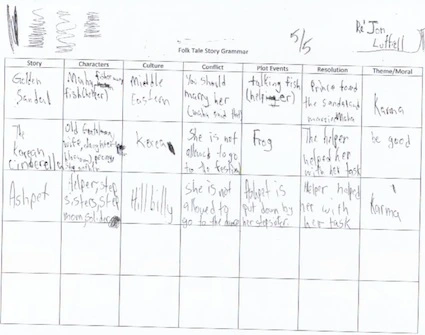

In English, John led students in a study of Chinese folk tales. Students read and studied five traditional tales from Stories from the Silk Road and researched five characteristics of Chinese folk literature. They had to identify each of these traits in one of the tales from the book. Students were asked to create their own character following the structures and characteristics of one of the stories, and participate in “mock” conversations or interactions with other students’ creative characters. After three such interactions, they completed a short children’s story with a moral or lesson, either by writing their own story or collaborating with a partner. The following images illustrate two such self-published books:

Story 1 (in appendix below)

Story 2 (in appendix below)

One student shared her vision of a young girl’s longing to travel the Silk Road as a merchant. A girl had little hope of realizing her dream until her parents consented to letting her go with her brother’s caravan. A diary (in appendix below) entries show the connection to a character from a long ago time in a faraway place.

To explore the history of the Silk Road so that students could add to their understandings of the cultural traditions, Jessica led students in social studies to create a life-size historical timeline (big enough to wrap around a classroom). It also displayed visually how the cultures overlapped each other. Students also completed a web quest concerning current and historical aspects of the Silk Road.

Maureen’s social studies classes, among many other cross curricular activities, used a website about Marco Polo to discover facts about Polo’s journeys and to explore and infer the purposes and significance of Marco Polo’s contributions through his travels. Maureen also found a wealth of information at Stanford University’s site, enabling students to involve themselves with maps, timelines, music and sights along the Silk Road. Students also created a large timeline that was color-coded to represent different countries. The students chose one interesting fact, printed it, and pasted it to the timeline so that it resembled a collage of information.

Jennifer’s math students determined distances of cities using the Pythagorean Theorem, which was known by the Babylonians, Indians, and Chinese. They read about the differences in the theorems between cultures, further illustrating the many ways that art, literature, and even mathematical formulas can hold secrets of people’s ways of thinking and seeing the world. As in Maureen’s classes, Jennifer’s students used formulas and logic to determine which route along the Silk Road they would take, considering the distance and the terrain that would need to be covered.

Both Jennifer’s and Maureen’s classes created symmetrical patterns (rotation and line of symmetry) using Islamic tiles as examples. Websites provided information on the history of mosaic tile practices enabled students to create a mosaic online. Students read about how the symmetrical designs (in appendix below) that came to be associated with Islamic art may have represented Islamic beliefs about order and balance.

One of the more popular learning stations involved the study of real silk worms along with an exploration of Islamic science. Students got first-hand looks at the underlying reason for the Silk Road coming to pass – silk. For Paul’s science classes, there were three distinct parts to this activity.

The first was an observation of living silkworms. Approximately 50-60 living silkworms were purchased from The Silkworm Shop. Using dissecting microscopes, hand lenses and blunt probes, students observed the anatomy and behavior of silkworms. Students were asked to sketch and label the anatomy of the silkworm, as well as record in words a description of their behavior, including both feeding and their response to being touched by a blunt probe. Because this packet was designed as a discovery activity, with the students having no prior knowledge or lessons regarding silkworms, poster-sized pictures of labeled silkworm anatomy and labeled silkworm life-cycle were provided for students to reference while they were observing and to help them label their drawings.

The second was a website excerpt reading/writing station. Students sat in a separate area of tables to read a handout containing information about the history of silk and silkworms, as well as interesting facts about silkworms that would appeal to middle school students. Students were also asked to write a haiku about silkworms. A poster explaining the structure of a haiku as well as several examples of haikus were provided at this station to help guide the students in this endeavor.

The third was a video viewing station. Students were provided with a table, chairs, and a laptop with several headphones attached to a listening station to view a YouTube video related to silk production and manufacturing. There are several excellent YouTube videos on this topic from which to choose. Paul used one titled "Dream Ribbon" which shows an artisan creating a silk bookmark out of silk harvested from silkworm cocoons in his own kitchen. Of course, the highlight of this station was the observation of the living silkworms. Give middle school students the opportunity to observe anything that's unique, weird and alive, and you have yourself a winning lesson!

The purpose of Paul’s second science activity was to provide students with a general overview of Islamic science during the time frame of the Silk Road, more specifically the 13th - 14th centuries. Once provided with some background information, students interacted with a series of images of scientific artifacts found at the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford, England, in an attempt to discern what each artifact or instrument was made of, it's purpose or function, and by whom, when or where the artifact was made. This discovery portion of the lesson was completed in pairs to allow for discussion and exchange of ideas, after which students immediately self-checked and corrected their ideas so they were not left wondering about the accuracy of their ideas. Checking their answers related to the artifacts also provided each student with the knowledge that, while every artifact or piece of "technology" had a scientific purpose or function, many were often originally developed and used for religious purposes related to Islam, such as measuring the time of day or the direction of Mecca, both essential for daily prayer. Students gained an understanding of the contributions and ideas provided by the Islamic world to science, as well as an appreciation for the interaction between science and religion.

Finally, Sue’s reading classes focused on reading Stories from the Silk Road, and composing “thinking” questions for each story. Previous to beginning the book, Sue had introduced the students to patterns of story structures in folk literature and her classes investigated several Cinderella stories to compare characters, problems, solutions, and themes. Similarities and differences were recorded on a semantic features chart.

Students read the stories in literature circles. Reciprocal teaching helped students to model and practice examples of good questions, and these became the focal points for the book study on the Google Lit Trip. Examples of the questions are:

“The Bride with the Horse’s Head”

- Why did the father kill the horse? Why did he regret his decision?

- Who was the silkworm?

- The trouble in this story happened because the parents were not happy with the promise they had made. What happened to the horse because of a broken promise? Have you ever broken a promise? If so, what were the consequences?

“The Jade Gate”

- How did Monkey find a way to get a horse for his friend?

- What did you learn about Buddhist beliefs from reading this story?

- Why is enlightenment so important?

“White Cloud Fairy”

- How can you tell that the White Cloud Fairy has sympathy for people?

- Why was the Sand God jealous?

- What do people who live near Dunhuang still believe about the Sand God?

Conclusion

The Google Lit Trip is still a work in progress at the time of this writing. It takes time to gather so much information, and still more time to decide what to include and what to leave out. According to exit interviews with students at the end of the unit, the Silk Road project was a success. Students revealed that they loved the interactive learning stations. They even suggested that they liked reading the stories, albeit in picture book form. We hope that this experience will encourage them to explore the traditional literature of other cultures and to become more consciously aware of the wealth of information and understanding that these tales offer. We believe that in order to appreciate who you are, you must also understand and empathize with other people. Our Silk Road journey and the forthcoming Google Lit Trip have and will continue to be our passports to global perspectives.

Bibliography

Gilchrist, C. (1999). Stories from the Silk Road. Illus. N. Mistry. Cambridge, MA: Barefoot Books.

Major, J. (1995). The Silk Route: 7,000 Miles of History. Illus. S. Fieser. New York, NY: Harpercollins.

Yolen, J. (1981). Touch Magic: Fantasy, faerie and folklore in the literature of childhood. New York: Philomel.

Sue Corbin teaches seventh-grade English and reading at Shaker Heights Middle School in Shaker Heights, Ohio and chairs the reading department. She teaches as an adjunct professor of graduate courses in reading at Notre Dame College of Ohio in South Euclid, Ohio and is designated as a master teacher in Ohio. Her articles regarding reading and children’s literature can be found in The Journal of Reading, Ohio Reading Teacher, Middle School Journal, The ALAN Review, The Dragon Lode, and Children’s Literature in Education under her former name, Sue Misheff.

Appendix

Silk Road Story One

Silk Road Story Two

Ida's Diary

February 27th, 220 A.D.

Dear diary,

In three days I will be thirteen. As I have said before, all I want is to travel the Silk Road and be a successful trader. I have been waiting for 5 years only to be turned down by my parents. By the power of Allah! They won’t let me do anything!“You’re just a fragile girl and your brother is a strong boy,” they say.

Isn’t that so nice. Sure, I’m not as strong as Sheesk but I am so much smarter than him! I bet I could make more of a profit in one trip than he could in 5! My parents are yelling at me to blow out the candle and go to sleep.

Goodnight, Ida

February 28th, 220 A.D.

Dear diary,

I am the luckiest girl in the whole world. Momma and Poppa have considered what I said and how important it is to me and decided to let me y\go! YAYAYAYAYAYAYA! I do have to go with my brother’s caravan but it’s better than nothing! I leave the night of the full moon so I must hurry and pack. I can’t wait!

Yours Truly,

Ida

March 3rd, 220 A.D.

Dear Diary,

I am leaving tonight. I have packed and can’t wait. Now that I am going, I realize how dangerous it will be. The bandits, sandstorms, and the possibility of getting lost. It’s really frightening, but I am determined to show I can do anything. I have prayed extra and I am itching to embark on my journey.

Ida

April 2nd, 220 A.D.

Dear diary,

It is almost a month inot our journey and there have been some difficulties and pleasant surprises along the way. We met a group of nomads who were nice enough but they had a very heavy accent. We have stopped at one trading city and it was so cramped. I was to watch my brother and learn but I think I cam up with more tips for him than he gave me. We haven’t had any trouble food or water wise but it is very hard work. We walk and ride our camels about 17 hours and sleep for 7. I can do it though. I am just as good as any boy.

Wish me luck,

Ida

Mosaic Tiles