Learning about Latin America through Multiple Texts in Middle School Classrooms

By Anne Hawkinson and Lauren Freedman

The Martin Luther King Middle School Literacy Community came together in September to plan our school year. Our group consisted of a literacy coach, social studies teacher, math teacher, science teacher, language arts teacher, a district liaison, and a consultant from Western Michigan. During the year, we met twice monthly to discuss and continue our learning about using texts sets of multiple materials and inquiry as an instructional model. At these meetings, each teacher shared what was happening in his/her classroom and discussed successes and needs. We also discussed interdisciplinary connections. The literacy coach, the district liaison to MLK and the WMU consultant served as support for the content teachers especially when it came time to focus on building the text set for our focus study and planning our interdisciplinary unit.

As a community, we also reviewed student work with the group splitting into trios (two content teachers and one of the support people) to discuss the strengths and needs of individual student’s products. The trios changed over the course of the year. These cross-disciplinary conversations led to deeper thinking as we worked toward the interdisciplinary unit. As we got to know each other better, we were also getting to know the sixth graders better within and across the content areas. We gained understanding of their strengths and needs regarding background knowledge, interest, and literacy development. We think this was a major factor contributing to the success of our unit on Central America, South America, and the Caribbean.

Background of Our Project: Anne Hawkinson, Literacy Coach

In 2008, WMU professors Lauren Freedman and Karen Thomas came to work with our staff at Hull Middle School. They proposed an exciting model for middle school learning: inquiry through engaging, multileveled, topic-centered text sets. With the financial support of the partnership between Benton Harbor Area Schools and Western Michigan University and the expertise of the librarian, Wayne Herman, we soon had our first “very heavy” tubs of nonfiction trade books that aligned with our units of study in science and social studies.

Over the next three years, as the building’s literacy coach, I worked with teachers to develop units that made use of the text sets. Although professional development was limited and “buy-in” was not universal, the response was enthusiastic among teachers who tried the inquiry model. I noticed a few things in particular as use of the text sets increased.

First, from repeated exposure to the text sets in different courses, students began to accept that the development of reading skills could occur in any subject area. Reading stamina also improved, as students spent more time with books. Background knowledge was increased as students were exposed to more far-ranging visuals and concepts than are typically offered by a textbook. Second, instructional efficacy increased as teachers began to plan units to include the building of reading and research skills. Teachers saw that in order for the text sets to be truly useful for student learning, reading and research skills needed to be explicitly taught. In social studies and science, categorization of information, note-taking, and expressing learning in original projects and prose came to be key objectives.

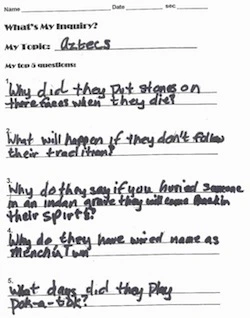

A good example of this growth in student skills and teacher expertise occurred in Ted Zahrt’s sixth-grade social studies class at the beginning of this past school year. Ted had used text sets in previous years, and brought this experience to bear as he developed a strong inquiry unit on Aztec and Mayan civilizations. He began by posing the essential question: “What elements make a civilization?” Together, the class built a list of features that distinguish a civilization from other ways people can form social groups. After a “wander and wonder” in the Mayan and Aztec text set, students formed questions to pique interest.

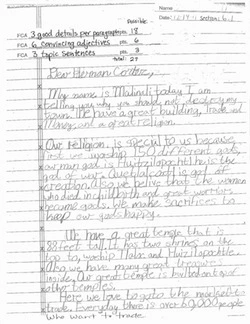

The students were then asked, “What evidence can you discover to show that the Mayans or Aztecs had a civilization?” As they began independent research, the students practiced categorizing information as they recorded their findings on a graphic organizer. To build note-taking skills, Ted led the class in frequent practice sessions, using excerpts from the text set. The students used the information they had gathered and evaluated their notes when they were asked to select three important ideas write about and illustrate on a pyramid.

In language arts, they explored persuasion, point of view, and audience by writing a letter to Cortez in the role of an Aztec or Mayan person. They wrote to convince Cortez not to destroy their civilization, using the text of their own notes as evidence.

When I debriefed this unit with Ted, he expressed confidence that his increased expertise in designing and managing the inquiry model had led to high engagement, increased reading stamina, and strengthened research skills among his students. He was also very pleased with the content learning that occurred.

The third major observation as we worked in the text sets had to do with their limitations. Our middle school student population contains a sizable amount of below-grade level readers. Most of these students fall in “just below”—at first glance, they may seem to be reading at close to grade level, but on closer inspection, lack of background and “think as you read” skills are prohibiting them from successfully analyzing more challenging texts. Others (perhaps 25% of the total population) are seriously struggling, being two or more grade levels behind in reading. Both these groups of readers do not handle complex informational texts well. They tend to flip through our text set books and look at the pictures. If they read, they have a hard time making meaningful notes. They are getting exposure, but not really experiencing the reading practice at their independent reading level that they need. I began to collect titles of books that would enhance the text sets and provide greater access for our struggling readers. The books with greater readability were dog-eared, while many of the texts were never touched. Our text sets needed revision.

Finally, higher-order thinking was increased if students were engaged in research projects that had a well-developed written component. This needed to occur more frequently, but when it did, as when Ted’s students wrote in language arts class about their Mayan and Aztec research, knowledge seemed to “stick”. This is not to say that posters made in science class about ecosystems are not a valuable learning experience. But to carry a topic to another class and really develop it through writing has no parallel in terms of guiding students to make big picture, real-world connections.

The MLK Learning Community Project: Lauren Freedman

We thought about this background this past spring as the sixth grade team embarked on the integrated research unit. We had previously developed a basic text set for the Caribbean, Central and South America, but it’s hard to get 30 sixth graders to do inquiry when there aren’t enough books they can actually read. An integrated unit using an enriched text set would help us bring our student researchers to the next level of meaning-making so we added new trade books to this text set. With the help of a local book store owner, we were able to add the missing pieces so that every student could engage with and learn through interesting and navigable texts. The teachers had experience with inquiry learning, which gave our planning a strong platform. We had experienced the way writing in language arts about social studies learning had enriched our students’ thinking. We were excited now to see how integration across all subjects, including science and math, would further deepen the experience.

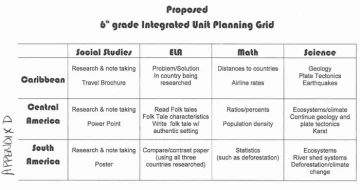

In our planning, the sixth grade team determined that organization was the key to the success of the project. Therefore, we met weekly on Thursday mornings to brainstorm ways to integrate the four content areas using Social Studies as the cornerstone. This chart shows the organization we decided to follow.

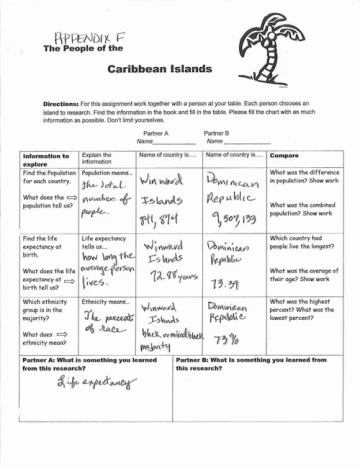

For the study of the Caribbean, the students began in Social Studies by wandering and wondering in the text set and asking questions. They then took notes. From these notes the students created a Travel brochure.

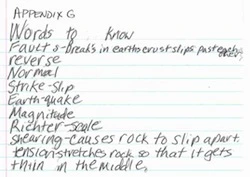

The students also gathered data that they used in Math to compare information about populations. In Science, the students began work on geological vocabulary and concepts. In Language Arts, the students discussed in small groups problems that were specific to Caribbean countries.

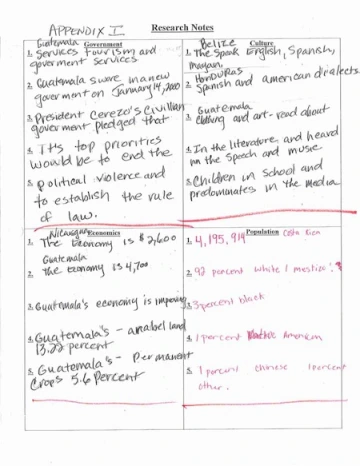

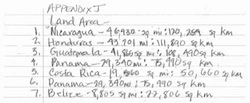

During the student of Central America, the students browsed, asked questions and took notes on Government, Culture, Economics, Population, History, Climate, Natural Resources, Landforms. Data on land area was taken to Math to compare the size of the Central American Countries. In Science, they used their notes on climate and landforms and continued the study of geological concepts.

The study of South American countries was cut short as the school year ended. So while our community’s plans did not all come to fruition, it was an important learning experience for us as educators. We observed the value of the students working independently and then sharing their findings. They demonstrated more interest in discussing the content they were learning as they were able to make connections across subject areas and were using the information gathered to think about life in this region as compared to their own in the United States.

Before the year ended, we were able to interview several trios of students about their experiences with the text sets and the notebooks and their observations about the integration across subject areas. In this video below,students express their enthusiasm about the project and discuss what they learned. They especially appreciated the ways in which the notebooks helped them organize and keep their papers from getting lost in the bottom of their backpacks. They could readily find the information they needed and could revisit their work by turning to the section of their notebook for a given content area.

After school year ended, we asked for volunteers to speak to the School Board at their meeting in June. Four boys agreed to speak to the board. The board meeting was at 6:00 p.m. At 4:45, the four boys came to MLK to talk about what they wanted to share at the meeting. These boys were not “ringers.” In other words, they were not the compliant, straight A students. Rather, they could easily get off topic in class, but could also be engaged if interested. At 6:00, we went to the meeting. Each of the four boys expressed some nervousness, but did extremely well. They talked about reading in the text set books (we brought about 10 with us and set them up on a table behind where the boys spoke) and taking notes in their notebooks. They brought their notebooks with them and showed the board each section and what the focus was for that section. They also talked about creating a bibliography of the materials they used. Then they shared their culminating brochures. It was quite impressive! In fact, the board and the audience gave them a standing ovation.

Anne Hawkinson is the Literacy Coach at Martin Luther King Middle School in Benton Harbor, Michigan.

Lauren Freedman is Professor of Literacy Studies at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo, Michigan and a consultant with Benton Harbor Area Schools.

MLK Learning Community members: Anne Hawkinson, Literacy Coach; Ted Zahrt, Social Studies; Joe Elsheikhi, Math; M’Shannon Rockette, Science; Matthew Walker, Language Arts; Don Pearson, District Liaison to MLK; Lauren Freedman, Western Michigan University Consultant