Inspiring Global Citizens in Rural Oregon

By Mariko Walsh

As a young Asian-American woman who grew up just outside of the major city of Portland, Oregon, teaching high school language arts in the rural community of Scio, Oregon has had its fair share of challenges. However, the most personally challenging part of teaching in this context has been the limited global and cultural awareness of my students. This limited awareness makes sense, considering exposure to these issues and experiences in their own school or community are narrow in scope and perspective. Scio is a wonderfully tight-knit community that has a population of 800, consisting of 95% Caucasian, 3% Hispanic, and 2% two or more races. Scio High School has 231 students, 92% of whom are Caucasian. That means that out of the entire school population there are only around 13 students who are not Caucasian. Scio is a wonderful community to work in, but I wanted to try and inspire my students to take interest in cultures across the world and possibly even create global citizens in the process.

As a teacher I’ve felt strong tensions seeing my students graduate and enter the world with such a narrow frame of knowledge. I often noticed students making small minded comments about other races or cultures, I believe, because they did not understand culture as a way of thinking and being in the world, and so dismissed cultural diversity as “different from me.” I wanted to expose my students to different cultures in a way that they could relate to and explore on their own; both the common values they share as well as the unique ways people had of living in the world.

Prior to my involvement with the Worlds of Words Global Literacy Communities grant, the only piece of literature we read in my 9th grade language arts class that explicitly focused on another race was To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee (1960). My students loved reading about the Tom Robinson trial, and became furious when the guilty verdict was delivered. Teaching To Kill a Mockingbird provided a great opportunity to start a conversation about prejudice and how we still see it today. I noticed that my students were able to easily connect to the events in To Kill a Mockingbird, not because they could relate to them, but because they were told in the voice of a child. Once I became involved in the Worlds of Words grant I knew that I wanted to bring in more global texts that utilized an adolescent narrator.

Selecting the Texts

For me, the first step was to identify what format I would use to create my global literature unit. I wanted to expose students to more than one global culture, but due to time constraints I was not able to have them read more than one book. I decided to utilize literature circles so that I could incorporate several texts in my classroom at once. Next, I searched for texts that focused on cultures from around the world and that used an adolescent voice for the narrator. I chose the following texts: Ashes by Kathryn Lasky (2010), Bamboo People by Mitali Perkins (2010), Home of the Brave by K. A. Applegate (2008), Milkweed by Jerry Spinelli (2003), and Words in the Dust by Trent Reedy (2010).

Ashes is narrated by a young girl named Gabriella who lives in 1932 Berlin. Through Gabriella’s eyes the reader learns about Hitler’s rise in power and the increasing hatred towards the Jewish community. Bamboo People is narrated by two teenage boys from different sides of the conflict between the Burmese government and the native Karenni people in modern day Burma. Having two narrators who were raised to hate each other brought depth to the novel, and exposed the reader to two very different cultures that exist in the same country. Home of the Brave is a novel that takes place in modern day Minnesota, but is narrated by a Sudanese refugee named Kek. This novel gives the reader a sense of the unique experience of a newcomer to the United States. Milkweed takes place in Nazi-occupied Warsaw during World War II and is narrated by a young orphan named Misha who survives the ghettos. Like To Kill a Mockingbird, the narrator is young and naive about what is going on around him. His somewhat childish observations allow the reader to come to their own conclusions about what is really happening. A young teenage girl named Zulaikha who lives in modern day Afghanistan narrates Words in the Dust. I was most excited to have my students read this novel because I often hear small-minded comments about people from the Middle East. Through Zulaikha’s narration, the reader is able to see what it is like to live in modern day Afghanistan. In addition to the novels using a child or adolescent narrator, I selected them because of the rich opportunities they presented for inquiry into global issues such as racism, genocide, immigration, and current events.

Creating Research Queries

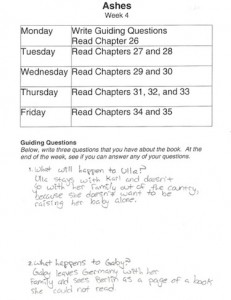

When the students chose the novel that they wanted to read and began meeting in their literature circles, I guided them in creating individual research queries. I wanted students to further research the cultures that they were reading about, but to choose aspects of that culture that really interested them. My students had never met in literature circles in my classroom before, so I still wanted to be able to nudge my students in the right direction while still giving them freedom to pursue their own interests and curiosities. I utilized two techniques to help my students identify their lines of inquiry. Every week each literature circle was given a reading schedule for that week. I carefully organized these reading schedules so that all of the literature circles would finish their book the same week. Along with their reading schedule there was space to write three “guiding questions” about their book as well as a space to record any additional notes or observations. Each individual student wrote three guiding questions at the beginning of the week, and then at the end of the week students shared the questions that they had written and the entire literature circle engaged in a discussion around these questions. Students recorded the group’s responses to their guiding questions, and kept them until their literature circle had finished the entire book. See Figure 1 for an example of the worksheet.

Figure 1.

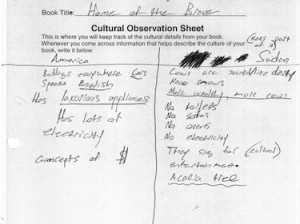

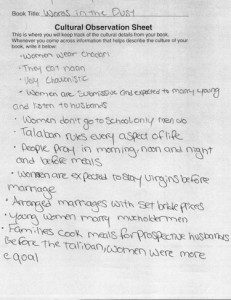

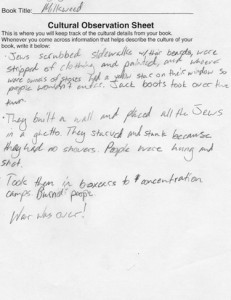

Another technique that I utilized was to have students record any differences or similarities they noticed between the cultures represented in the books and their own. These lists provided great insight into not only what made the cultures in the books unique, but also what my own students had in common with the characters of a culture. The students actually found it easier to find similarities than differences between their own cultures and the cultures in their book. I gave each student a “cultural observations” sheet on which to record these differences and the students kept them and filled them out the entire time they were reading their books in their literature circles. Here are some examples:

Figure 2. This student chose to compare and contrast the differences in Home of the Brave between the narrator’s native country of Sudan and their new home in America.

Figure 3. A cultural observation sheet from the Bamboo People literature circle.

Figure 4. A cultural observation sheet from the Words in the Dust literature circle.

Figure 5. A cultural observation sheet from the Milkweed literature circle.

I found that both of these strategies encouraged my students to critically analyze their books and the unique differences they identified while exploring another culture. I was continually impressed with their insightful observations, but was even more excited by how analyzing the differences between their culture and the culture of their book made my students realize how many similarities they shared as well.

I wanted students to share what they learned about the cultures represented in the novels with each other so the entire class collectively gained the new knowledge and insights about cultures they had learned about through their readings and discussions. I invited each literature circle to choose topics to further research on their book’s culture and then present a slideshow to the class sharing their information. The students chose their research topics by looking back over their guiding questions and cultural observations to see what topics they had the most questions about or made the most observations about as they read their book. I wanted students to pick topics that they were genuinely interested in, not topics that I assigned to them. Students really enjoyed conducting their research, and the slideshow presentations were incredibly insightful and educational. See Figures 6, 7, 8, and 9 for examples of slides from the students’ presentations.

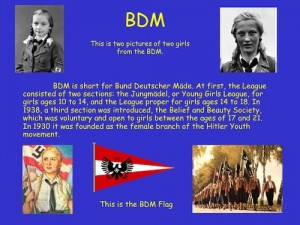

Figure 6. A slide from the presentation by the Ashes literature circle.

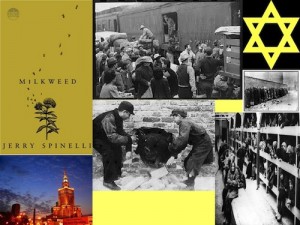

Figure 7. A slide from the presentation by the Milkweed literature circle

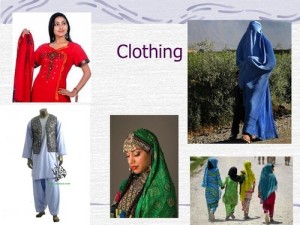

Figure 8. A slide from the presentation by the Words in the Dust literature circle

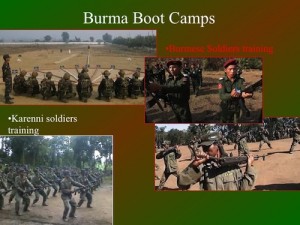

Figure 9. A slide from the presentation by the Bamboo People literature circle

Reflecting on the Experience

After the literature circles had completed their research I asked students to reflect on their experiences with their novels. I asked what they learned about their new culture, and if they found the global literature unit interesting. Here are a few of the sample responses I received:

I liked my book because it was interesting to learn about the culture. I didn’t know anything about the African culture before I read my book, and I learned a lot. (Justin, Home of the Brave)

I enjoyed reading about the SA and the SS, and also learning more about Hitler. I had no idea that people were so angry about losing World War I, and now I understand how Hitler was able to get so much power. I learned a lot and I liked how it was from a girl about my age. (Jessica, Ashes)

I’ve always been interested in the Holocaust, and this was the first book I’ve read where the narrator of the story is a young kid. It was really interesting to read about what Misha saw and experienced, and it gave me a really neat look at the Holocaust and what it would have been like to be there. (Chris, Milkweed)

I really liked reading about how different it is to be a girl in Afghanistan, like how girls can’t go to school or learn to read. I really liked how the book took place recently because I am always hearing about our troops over in Afghanistan. It was cool to read about what our soldiers are doing over there, and how they are trying to help the people. (Melissa, Words in the Dust)

I thought it was really interesting how scared the Burmese government was of its own people. I can’t believe they had a war over it. I liked all of the details in the book about the Karenni culture, it was fun to learn about them. (Trevor, Bamboo People)

These responses truly reflect the excitement that my students and I experienced as we engaged in critical analysis and research queries together. It was thrilling to witness my students discover the knowledge that they were not just a citizen of Scio or Oregon, but that they were a global citizen.

I cannot wait to teach this global literature unit again to a new group of freshmen. I plan to add to my novel collection to offer more choices and cultures to my students, which I believe will benefit the unit and increase my students’ cultural awareness. I have already begun talking with the social studies teacher at my high school on ways that we can create interdisciplinary connections throughout this unit. We have decided that we will create a Current Events assignment at the end of the unit where students relate what is happening in their book to what is currently happening in the world. Along with the success of my global literature unit, my experience with literature circles has been so positive that I am now trying to incorporate literature circles in the other classes that I teach. I have found that literature circles are a great vehicle for student-led inquiry, insightful discussions, and inquisitive learning. I believe that this experience has helped me give my students the tools to continue to stay informed and curious about the world around them, and I am so thankful for that.

References

Applegate, K. A. (2008). Home of the brave. New York, NY: Square Fish.

Lasky, K. (2010). Ashes. New York, NY: Penguin.

Lee, H. (1960). To kill a mockingbird. New York: Grand Central Publishing.

Perkins, M. (2010). Bamboo people. Watertown, MA: Charlesbridge.

Reedy, T. (2010). Words in the dust. New York, NY: Scholastic.

Spinelli, J. (2003). Milkweed. New York: McMillan.

Mariko Walsh is an English teacher at Scio High School in Scio, Oregon. She is currently on the Executive Board for the Oregon Council for Teachers of English and the Oregon Writing Project.

WOW Stories, Volume IV, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesiv2/.