Children Revaluing Themselves as Readers and Writers: Critical Dialogues about Identity in Children’s Literature

By Maria Perpetua Socorro Liwanag, Koomi Kim and Peter Duckett

We wanted to understand how elementary students make critical connections as they transact between texts and their own social world (Dyson, 1993) and so invited students to engage in critical dialogues in reader response journals to explore authors’ ideas as their own. Reading aloud books such as My Name is Sangoel (Williams, 2009), Rene has Two Last Names (Colato-Lainez, 2009), and My Name Jar (Choi, 2001) offered our students an opportunity to actively transact with the text. In Williams’ (2009) book, an elderly character tells the child: “You carry a Dinka name. It is the name of your father and of your ancestors before him…You will be Sangoel. Even in America.” (n.p.). By sharing children’s literature that explores names and identities, our students engaged in a journey of revaluing themselves as readers and learners.

Students from an elementary school in the northeast of the United States were participants at an after school literacy center where read aloud and independent reading sessions are a regular part of a reading practicum course for university graduate students. The practicum provides the graduate students with a culminating experience in assessing and instructing students with reading difficulties. The school has 400 K-5 students and 86% are white, 14% Black, Hispanic, Asian, and other races and ethnicities. Approximately 60 first through fifth grade students have participated since we started this project in Spring 2010. Each semester, we have 15-20 students in the Literacy Center. The majority of the students are white. At least five percent of the students who participate in the literacy program are English Language Learners (ELLs). This percentage also mirrors the demographic population of ELLs in this rural school. Also, the majority of the students who attend the after school reading program were considered “struggling readers” by the school based on their test scores. For read aloud sessions, we intentionally selected multicultural children’s literature to uncover how elementary students explore their own names and identities as well as those of others through conversations in response to the books.

We share multiple ways to use authentic multicultural children’s books to engage children as literate beings with our graduate students. We focus on various themes for book selections which include names and identities, families, friendship, and overcoming personal struggles. We regularly observe and examine students’ oral and written responses to uncover how the use of multicultural children’s literature focusing on names and identities builds a learning community and connects elementary students through critical literacy engagements. For this vignette, we share our experiences and what we’ve learned from engagements with multicultural children’s books that focus on names and identities (see Table 1). In this study, we highlight student responses to understand how they revalued themselves as readers and learners in responding to multicultural text sets. We include oral and written responses of five students as focal points and provide the general context of the article.

Choosing a Theme

Martinez & Roser (2011) have explored how professors of children’s literature design their courses. They mention Kathy Short, who “believes that organizing books around themes is much more significant for children” (p.16). As an opening engagement, we select stories about individuals with diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds, and characters that have diverse names because we know this theme of diversity will engage students. Each week we read picture books, discuss them with the whole group, and then invite students to participate in a variety of response activities. These activities include writing free responses, sharing reading, conversing about books, writing responses to the books, creating posters, writing poems, and creating illustrations/drawings.

In this article we include specific examples using students’ responses to these books:

Book Title | Author | Summary |

|---|---|---|

| My Name is Yoon | Helen Recorvits | A Korean-American girl wants to explore other English names before sharing her name with her new friends in school. |

| The Name Jar | Yangshook Choi | Unhei is a Korean-American girl who learns to show her classmates why she has chosen to keep her name and what her name means. |

| My Name is Sangoel | Karen Lynn Williams | A boy who comes to America and wants to be called Sangoel, even in his new home. |

| Rene has Two Last Names | Rene Colato-Lainez | Rene wants his classmates and teachers to know that he has two last names, which represent his two sets of grandparents from his father’s and mother’s sides. |

The children’s books we selected deal with intricate social and cultural issues concerning identities, especially dealing with the socioculturally, linguistically and ethnically diverse names of main characters who are living in the United States. We choose these books as an invitation for students to view multiple perspectives about children’s names and identities so that they can see and examine themselves and other cultures in the books they read (Freeman & Lehman, 2001; Sims, 1983).

In the following sections, we describe what we have learned about students’ insights through conversation and written responses to these books. We use a lens of critical literacy (Vasquez, 2010; Wink, 2010) to understand how children position themselves socially and transact with multicultural literature.

Building a Learning Community

It has been an engaging learning experience for us to understand how students respond to these selected read aloud choices. Cai (2002) reminds us that “it is not enough to know multicultural literature itself; it is imperative that we know how children will respond to it” (p.171). Our goal is to have students personally connect with a topic that invites them to share their thoughts with the group, to go in depth and think about the issues themselves, and to critically examine how the topic can influence their thinking. We have learned that students are genuinely interested and engaged whenever they are introduced to culturally and socially relevant children’s literature. Our students are eager and ready to read and listen to the reading of authentic multicultural children’s literature in every session because the books we selected are worth reading and talking about.

We explored the topic of names and identities in an effort to understand how children use the themes and topics to dig deeply into concepts that are as personal as names and as complex as personal identity. Issues like losing one’s name in My Name is Sangoel (Williams, 2009) or being teased because of one’s name in Rene has Two Last Names (Colato-Lainez, 2009) and Unhei in The Name Jar (Choi, 2001) are topics about which our students have something to say. Providing opportunities for students’ voices to be heard about the issues presented in texts helps drive the learning process (Lewison, Leland, & Harste, 2008, p.67).

We observed how committed students were to helping one another during a pre-reading activity for My Name Is Yoon (Recorvits, 2001). After we showed them the cover of the book and read the title of the story before reading the book, we asked children where they thought the character of the story was from. The students shared their knowledge and experiences. Most responded that Yoon could be from Japan or China. Some mentioned Mexico, but later changed their response to either Japan or China as well when someone in the group said “it’s the name.” The students were quick and eager to share their predictions and assumptions. By listening to differing responses, students validated each other’s knowledge. This demonstrates how students “use others to help them understand” (Martinez-Roldan, 2005, p.23). In general, exploring names and identities through the selected multicultural children’s books motivated the children to share thoughts, feelings and experiences. We also learned that they freely share what they know and that they like to write about their experiences. Short (2011) reminds us that children’s discussions about books enabled them to “think with each other” (p.52). These broad ranging discussions “focus on their processes of thinking, not a final answer” (p.52).

In later sessions, students began to reflect further and make multiple connections through their personal interpretations of the literature. Here is an example of an interaction with Rene has Two Last Names (Colato-Lainez, 2009). Note that pseudonyms for children’s names have been used throughout the article.

Teacher: So why do you think Rene has two last names?

Bree: Probably his mom and dad are divorced.

Johnny: He could be like me, I was Johnny in Ghana and I’m John here now and that’s probably also true with Rene.

Here, Bree shares a personal hypothesis about family relationships while Johnny makes critical connections by drawing on his own experience in the two countries where he has lived. These responses demonstrate how children position themselves or are critically aware of their own sociocultural contexts to make critical and reflective connections. Bree is a third grader who is a monolingual English speaker and was referred to our literacy center because she needed additional support in reading and writing. Johnny is a fourth grader who came to the United States from Ghana when he was seven years old. He belongs to a large family and is multilingual. He receives ESOL instruction twice daily to support his English language development. He joined the literacy center because he also needed extra support with literacy. Connecting their experiences with the multicultural children’s books provided our students with opportunities to revalue themselves as readers and thinkers in much the same way as the characters in the story valued their own names and personal identities.

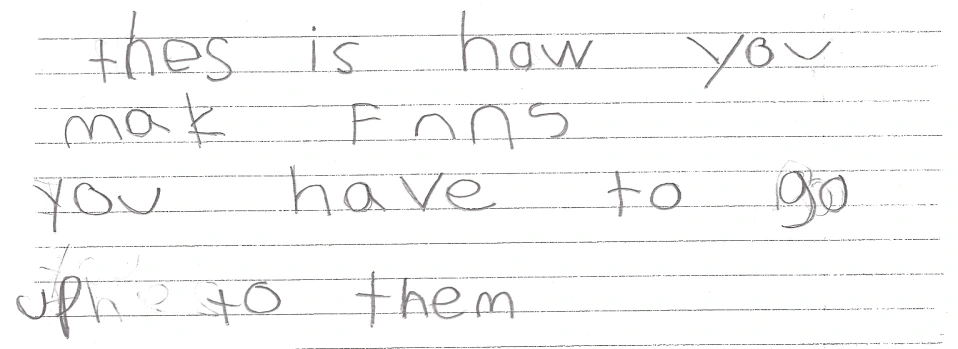

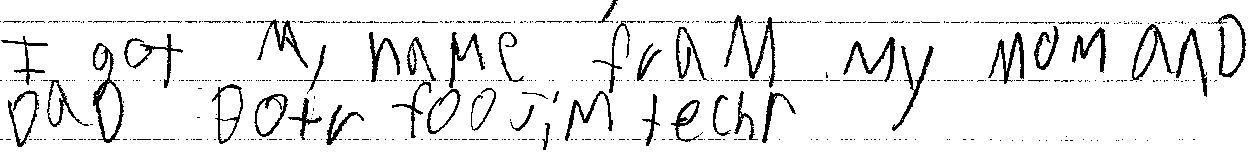

The following week, we read The Name Jar (Choi, 2001).The students wrote how they could be a friend to a new student in their school.We asked Carlyn if we could use her writing sample to share with the class. She was very pleased that we had selected her writing piece to share. Carlyn is a monolingual English speaker. Carlyn’s written piece provided us with an opportunity to communicate as a group and become comfortable with each other. Carlyn shared the following piece with us:

Everyone in the group had a chance to approach another person to talk about their thoughts on The Name Jar. We are discovering how struggling readers in our center make reflective personal connections with the stories and share ideas with one another, and how this contributes to the students revaluing themselves as readers and learners.

Writing about the Self to Connect with Others

As teacher educators, we use multicultural children’s literature in our curriculum because it allows students to reflect on cultures that are different from their own (Harris, 1997; Henderson & May, 2005) as well as to examine their own cultural and linguistic backgrounds. We select stories about children’s names and identities and invite them to think and talk about their own names. We also negotiate with our students on the selection of writing topics. They are encouraged to be critical learners in their understanding of social issues as well as themes which are presented in the stories we read. In the following example, Miranda chooses to write personal information about her family after reading and listening to Rene has Two Last Names.

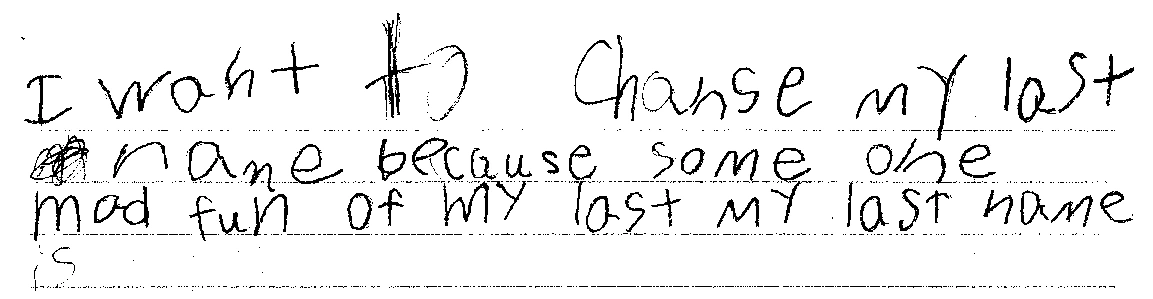

Miranda speaks Spanish and English. Like Johnny, she receives ESOL instruction. She decided to rewrite her own understanding of the story by situating her name based on the vocations of her parents. Rene, the character in the story, explains why he has two last names to his classmates by sharing his family tree. He acknowledged that his grandparents helped him become who he is now. He cannot just be Colato from his mother’s side or Lainez from his father’s side. He is Rene Colato-Lainez. In much the same way, Miranda acknowledged her family name but also added the vocations of her dad as a doctor and her mom as a teacher. By writing the origin of her name, she linked her own experience with that of Rene (Colato-Lainez, 2009) who also explained his last name in the story and linked them with his family’s talent and work. We see how Miranda was re-writing her own world in much the same way as Rene did in the story. This provides us with a platform to share more about ourselves and our families. Another example comes from a fourth grade monolingual speaker, Mark, who forged a sense of sharing when he wrote in his reader response journal and shared the following in our class:

Social issues such as name-calling and labeling became a focal point of our discussions when everyone agreed that it’s not good to make fun of other people’s names, especially concerning ethnic names. Mark’s response above was also his own way of sharing information about his name after we read and listened to My Name is Sangoel (Williams, 2009). In the book, Sangoel goes to America to start a new life with his family but also finds that people have trouble pronouncing his name. His teachers and classmates in his new school do not know how to say his name. Sangoel doesn’t like it when his name is mispronounced. In the end, he creates a rebus of his name to help his new teachers, classmates and friends to pronounce his name the way it should be said. Sangoel’s situation resonated with Mark as he wrote about how others also “made fun of his last name” because it was difficult to pronounce. By sharing his writing with others, children had an opportunity to talk about issues surrounding name-calling and labeling. This book also helped them be reflective as we examined how name-calling and labeling can make a person uncomfortable and why it’s important to respect others. Wilhelm (2009) talks about how “reflection is essential to critical literacy and to effective teaching” because reflection privileges our experiences as “a source of knowledge” (p. 37). In this case, Mark’s writing helped us validate his experience and knowledge as a teachable resource for helping others become better individuals. Students had a starting point to share personal information and to explore family stories and names because of their experiences reading and listening to authentic multicultural literature (Short, 2011; Cai, 2002; Mathis, 2011).

Examining students’ initial reading responses and journal entries helped us understand how names and identities can be topics for exploration. Even students who do not usually like to read and write are eager to read their work aloud to the group. They are motivated to read and write about names and about themselves or their identities because they are the experts in their stories about their names/ identities. Our students develop positive self-concepts while simultaneously learning about other cultures.

Conclusion

Students in our literacy center helped us understand how they developed and grew as literate beings. Our students engaged in authentic writing events. The culturally diverse literature provided them with opportunities to extend the story and apply concepts and ideas “to and from” their own lives.

The students all showed that their life experiences transact with the stories we read and listened to in class. While they each have different cultural and linguistic backgrounds compared to the stories they read and listened to in class, they experienced a sense of connectedness through the topics and themes found in the literature. By thinking about the characters’ experiences, they generated their own insights and meanings. The children in the literacy center revalued themselves as readers and learners as they rewrote their own stories and offered their own perspectives. Like the characters in the multicultural children’s books, students had the opportunity to discuss and offer their own perspectives. Orally sharing and writing stories about names and identities helped them find meanings in their own names and identities while also creating a sense of personal ownership for learning.

References

Cai, M. (2002). Multicultural literature for children and young adults. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

Dyson, A. (1993). Social worlds of children learning to write in an urban primary school. New York: Teachers College Press.

Freeman, E. & Lehman, B. (2001). Global perspectives in children’s literature. MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Harris, V. (1997). Using multiethnic literature in the K-8 classrooms. Norwood, MA: Christopher Gordon.

Henderson, D. & May, P. (2005). Exploring culturally diverse literature for children and adolescents. Boston: Pearson.

Lewison, M., Leland, C., & Harste, J. (2008). Creating critical classrooms: K-8 Reading and writing with an edge. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Martinez, M. & Roser, N. (2011). What’s going on in children’s literature classes? In A. Bedford & L. Albright (Eds.) A master class in children’s literature: Trends and issues in an evolving field (pp. 3-21). Urbana, IL: NCTE.

Mathis, J. (2011). Multicultural literature. In A. Bedford & L. Albright (Eds.) A master class in children’s literature: Trends and issues in an evolving field (pp. 93-108). Urbana, IL: NCTE.

Sims, R. (1983). What has happened to the “all-white” world of children’s books? Phi Delta Kappan, 64, 650-653.

Short, K. (2011). Reading literature in elementary classrooms. In S. Wolf, K. Coats, P. Enciso, & C. Jenkins (Eds.) Handbook of research on children’s and young adult literature (pp.48-62). New York: Routledge.

Vasquez, V. (2010).Getting beyond “I like the book”: Creating space for critical literacy in K-6 classrooms. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Wilhelms, J. (2009). The power of teacher inquiry: Developing a critical literacy for teachers. Voices from the middle, 17 (2), 36-39.

Wink, J. (2011). Critical pedagogy: Notes from the real world. Boston: Pearson.

References for Children’s Literature

Choi, Y. (2001). The name jar. New York: Dell.

Colato-Lainez, R. (2009). Rene has two last names. Texas: Piñata Books.

Recorvits, H. (2003). My name is Yoon. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

Williams, K. & Mohammed, K. (2009). My name is Sangoel. Michigan: Eerdman.

Maria Perpetua Socorro U. Liwanag is an assistant professor at SUNY Geneseo.

Koomi Kim is an Associate Professor in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at New Mexico State University.

Peter Duckett is Curriculum Coordinator and Director of Professional Development at Cairo American College in Cairo, Egypt

WOW Stories, Volume IV, Issue 6 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesiv6.