Download as PDF

Freedom and Justice for All: Exploring Black Lives Matter and the Significance of Civil Disobedience

By Desiree Cueto and Shannon Clowes

Not since the Civil Rights Era has national attention been as focused on issues concerning the African American community as it is today. Over the past five years, a significant number of wrongful death cases and those involving the use of force by police have played out in the media. Most notably the deaths of Trayvon Martin, Oscar Grant, Sandra Bland, Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, Michael Brown and Freddie Gray dominated news headlines and spurred unrest between the African American community and the criminal justice system (Tatum, 2015). Black males are 21 times more likely to be shot by police than are their White male counterparts. In response, #BlackLivesMatter became a trending topic on social media and has since grown into a widely recognized movement.

Because schools do not exist in vacuums, highly politicized issues such as racial injustice often find a way into classrooms (Hess & McAvoy, 2015). It was not surprising that some of Shannon Clowes’ fifth grade students wanted to discuss what they knew about the Black Lives Matter Movement and what they had heard about the untimely deaths of so many African Americans. When Shannon and I met to discuss what was happening in her classroom, she shared:

My students read news stories and we regularly discuss current events in class. They get into impassioned conversations about what is happening in the world. Some students are enraged that innocent people are being killed and I know this is a topic we need to address.

Despite being a new teacher—only in her second year—Shannon is committed to teaching for social justice. Inspired by Jonathan Kozol’s (1991) Savage Inequalities, she entered the profession believing that effective teachers empower their students to take action. With that in mind, she embraced inquiry as a stance toward teaching. Short (2009) defines inquiry as “a collaborative process of connecting to and reaching beyond current understandings to explore tensions significant to learners” (p.12). Shannon shared that, “the unit was inspired by students’ genuine interest in the subject.” The African American students in Shannon’s class prompted the conversation about #BlackLivesMatter. However, she believed that racism was an essential issue to address with all students. When I asked her if she had any reservations about presenting this unit she shared:

I have a few concerns about discussing racial issues. Once we start to really talk about it (race), I don’t not know what they might say, do, or feel. My primary concern is that they talk with each other, and learn from one another. They are beginning to form opinions about a topic that is extremely complex, bringing to the table with them very different life experiences and knowledge.

While the Caucasian students in Shannon’s class had heard about the Black Lives Matter Movement, many of the African American students and other students of color had a deeper understanding of racism based on their own personal encounters. A challenging aspect of doing this work for Shannon was to educate every student (and herself), and at the same time ensure that all students felt safe and respected.

In terms of racial demographics, Peter Howell Elementary closely resembles the broader school district: White (27.16%); African American (9.85%); Hispanic (56.72%); Native American Indian (6.27%). However, it is above both the state and district averages for the percentage of students eligible to receive free or reduced-price lunch. On average, 53 percent of students in TUSD qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, while 70 percent of students at Peter Howell do (LaFleur, 2014). The hardships of life have been real for most of Shannon’s students, and she knew that each of them would connect on some level with the topic. But, racial issues can be particularly sensitive in nature and difficult to navigate. For that reason, Shannon appreciated the unique space that literature provided to support the discussion.

What is Civil Disobedience?

There are a number of books that depict acts of civil disobedience and non-violent protests. Some of the titles we located: The Boston Tea Party by Russell Freedman (2012), Brave Girl: Clara and the Shirtwaist Makers’ Strike of 1909 by Michelle Markel (2013), Dolores Huerta: A Hero to Migrant Workers by Sarah Warren (2012), Gandhi: A March to the Sea by Alice McGinty (2013), Harvesting Hope: The Story of César Chávez by Kathleen Krull (2003), ¡Sí, Se Puede! / Yes, We Can!: Janitor Strike in L.A. by Diana Cohn (2002), Sit-In: How Four Friends Stood Up By Sitting Down by Andrea Davis Pinkney (2010) and We March by Shane W. Evans (2012). However, only one book, Daddy, There’s a Noise Outside by Kenneth Braswell (2015) specifically addressed the Black Lives Matter Movement. This book portrayed an African American family living in an urban community. After the two children are awakened by noises outside their window, they ask their parents to explain what happened. The family sits down to discuss what it means to protest and the reasons why members of their community are currently protesting. Through this conversation, Braswell located the Black Lives Matter Movement within the larger historical context of civil disobedience and the African American struggle for equality and justice.

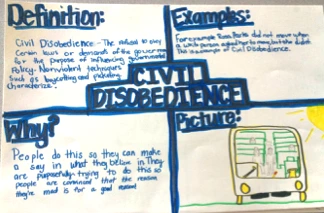

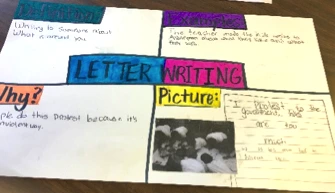

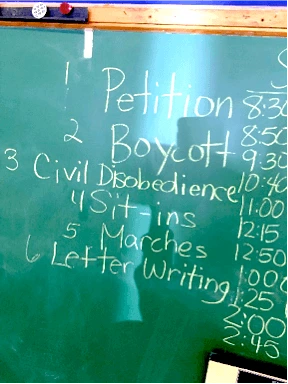

Because we could find no other children’s books about the Black Lives Matter Movement, Shannon downloaded images from the internet. The students also visited the websites, blacklivesmatter.com. Shannon asked students to work in pairs to browse the text set and internet resources. First, students were instructed to try to locate the different forms of civil disobedience mentioned in Daddy, There’s a Noise Outside (boycotts, marches, speeches, sit-ins, petitions, and letter writing campaigns). Next, students were asked to do a quick write answering, “What did you notice?” and “What did you wonder about?” At this point, the goal was simply to get students to explore the concept of civil disobedience. Shannon concluded the lesson by having students web their thinking about the concept of civil disobedience.

The term “civil disobedience” is defined as a strategy of non-violently refusing to cooperate with injustice.

Exploring Injustice

Shannon revisited ideas from the previous lesson by asking students why they thought some citizens might engage in acts of civil disobedience. Students offered a variety of responses including: “Because they didn’t like the laws.” “They did not agree with what was happening.” “They wanted rights.” Shannon wrote the word “JUSTICE” on the board. She explained,

When our founding fathers wrote the American Constitution, “justice” was a set of laws put in place to make sure that every citizen would receive equal protection under the law. Justice is what guarantees that certain rights can never be taken away or destroyed. Laws of justice are in place to ensure that all people are treated with fairness.

The purpose of the lesson was to encourage students to make deeper connections between civil disobedience and injustice. Additionally, Shannon wanted to move students closer to an understanding of how the African American community has historically and continuously struggled for justice. She shared,

I hoped that students would look at how African Americans have united and mobilized throughout history in order to combat injustice. I also wanted my students to come away from the text set with a deeper understanding of the injustices that continue to take place in our country. Perhaps the books will show them what they can do in the face of it.

The set of books spanned African American history from slavery to the present. Within the text set, authors examined injustice through the protagonist’s efforts to either circumvent established law or to change it. Before allowing students to browse the books, Shannon asked them to focus their attention on the actions various characters in the books took, and why. She felt it was important that the students understand that people were fighting for rights that should have been theirs simply because they were born in America.

While the students browsed the books, Shannon posted the words to the Pledge of Allegiance on the board. As they read, students marked the books with sticky notes, documenting actions and reasons for the actions. They met in small groups to discuss their findings and to web new connections they made to the word “injustice.” Shannon wrapped up the session by calling the students’ attention on the Pledge of Allegiance. She explained,

As time progressed, Americans realized that all men and women were not being treated equally and something needed to be done to grant the same rights guaranteed by the Constitution and Declaration of Independence to everyone. For example, African Americans, women, and immigrants did not have the same rights as White men. Each of these groups were excluded from this protection because they were not viewed as citizens. People from these groups fought for many years to also benefit from the rights guaranteed by the Constitution.

Students shared in small groups about what they knew about the injustices experienced by African Americans, women and immigrants. Then they worked together as a class to complete a consensus board about what they had learned: "People were grouped together based on shared similarities such as skin color, gender or immigration status." As a result, these groups were often treated differently and were not afforded equal rights. Before exiting, students were asked read the Pledge of Allegiance and to Free Write their thoughts about whether or not “justice for all,” applies to all people today.

Stepping Back to Scaffold

When we reviewed the students’ responses to the previous lesson, it was evident that most understood that there was injustice in world and that certain circumstances warranted protest. However, it did not appear that students were having the kind of “lived through” experiences with the texts that we had anticipated (Rosenblatt, 1978, p. 24). Because the majority of the books we presented were set in distant history, we surmised that the students were not easily making text-to-self or text-to-current world connections. Some of the books may have seemed less relevant, even to the African American students. Moreover, we saw little evidence of what Shannon had hoped for in terms of the students’ readiness to take action for social change. In one-to-one interviews, students reported feeling powerless to intervene in situations they felt were unjust.

The students needed to draw upon their experiential backgrounds to make sense of the text. Revisiting the Inquiry Cycle (Short, 2009), we knew that we needed to provide a space for them to define injustice in terms that reflected their own cultural and historical context. For the next lesson, Shannon introduced Memory Maps and guided students in a discussion about places they have either witnessed or experienced injustice in their own lives. The students represented their experiences on large pieces of chart paper. Because the Memory Maps were constructed in a diverse setting, Shannon hoped that the engagement and subsequent small group discussion might also facilitate cross-cultural understanding. She concluded with a forum for students to share their maps and reflect on their current stance about injustice.

My students made personal connections right away and they were quick to share instances of injustice in their own lives – like getting blamed for something they did not do or being treated differently because of their gender or being called names. Some students even mapped out places where they had been referred to in racially derogatory terms.

While conversations surrounding the maps allowed the students to see where their experiences diverged and overlapped, Shannon was not convinced that they were making the kind of critical connections that might inspire them to take action against injustice. When we met again, she reported that students, “Listened attentively to one another. They even demonstrated empathy by looking shocked or angry when a classmate recalled being verbally insulted.” However, racially charged insults did not necessarily register as being significantly different from other kinds of insults. In light of our focus on the Black Lives Matter movement, this was particularly troubling. Lopez (2000) writes, “When people absorb racial ideas cognitively, treating racism as an accepted, expected part of the natural order, race functions institutionally” (p.1806). We wondered how much students had absorbed and how they were processing stories in the news and on social media. With the public’s attention (and our unit) focused on violent forms of racism—wrongful death and police brutality—we also questioned whether students were becoming immune to less overt forms of racism. We wanted to make sure that students understood that all forms of racism are interconnected and that racism is about division and power.

Tackling Racism

As the unit progressed, Shannon wanted to focus on deconstructing racism with the premise of empowering students to take action and promote a positive change. To accomplish this, we considered how she might present the text set in a way that bridged the gap between historical racism and present-day racism. She also wanted to encourage the students to imagine a world free of racism. Short’s work on critical inquiry, which highlights the need to focus on issues of power and on questioning oppression, was instrumental to the way we considered engaging students in this inquiry. Short (2003) states that, “Readers ought to be challenged to critique and question ‘what is’ and ‘who benefits’ as well as to hope and consider possibility by asking ‘what if’ and taking action for social change.

We had already spent a good amount of time getting students to think about “what is.” For example, students could define civil disobedience, name historical figures and groups who experienced injustice, and speak about instances of injustice in their own lives. Because the focus of our unit was Black Lives Matter, the texts we selected reflected African American history and highlighted the racial discrimination and ensuing injustices that Black people have endured. After multiple text set readings, students easily made connections between injustice, inequity and racism. A take away from an early lesson was that society tends to group people who look alike and consequently treat them differently as well. Students needed to start to ask the question, “who benefits?”

Who Benefits?

There are biological reasons as to why people look different from one another. However, race as we understand it today is a social construct. Assigning significance to skin color, with darker skin tones representing inferiority, has been linked to slavery. Negative perceptions of particular races justified inequalities as being natural. Critically examining these ideas with students is important because they shape students’ interactions and attitudes towards different racial groups. Each of the books in the text set provided a space for students to think critically and to question who benefits from social constructs. Short (2003) recommends teaching students to “read against the grain of texts to question dominant messages and uncover the different layers of meanings, beliefs and perspectives embedded in a book.” Shannon modeled this approach, using the book White Socks Only by Evelyn Coleman (1996). The book begins,

When Grandma was a little girl in Mississippi, she sneaked into town one day. It was a hot day—the kind of hot where a firecracker might light up by itself. But when this little girl saw the “Whites Only” sign on the water fountain, she had no idea what she would spark when she took off her shoes and—wearing her clean white socks—stepped up to drink.

Based on the previous stories they had read, the students immediately anticipated trouble. Some students gasped. Others shook their heads. This was the empathy we hoped they would express. However, the goal was to move from aesthetic responses to critical analysis. As she read aloud, Shannon paused to ponder questions, such as, “When a big white man accosts the little girl and threatens to whip her, who benefits?” Shannon commented, “The only person who seems to be okay with what is happening is the man who is trying to stop the little girl from taking a drink.” She turned to the class and asked if the man’s actions reminded them of something else that they have learned about. The students connected the man’s action to the word “segregation,” which they had read about in other books. The word “segregation” was also posted on a growing list of words on the class’s word wall. Shannon reminded them that, “The practice of segregation was put into place by the dominant group in order to maintain an imbalance of power. It was used to support injustice.”

The issue of power was also important for students to consider. We intentionally selected books that presented a shift in power—a moment when the character or the community resisted being oppressed by the mainstream or dominant group. For example, before “the big white man” in White Socks Only was able to remove his belt to whip the little girl, bystanders from the African American community removed their shoes and defiantly drank from the fountain. The actions of the bystanders showed their strength and willingness to fight the injustices that were governing their lives. This action really resonated with Shannon’s students. Most of the students related the question, “who benefits” to bullying and how bullies seek to maintain power. Some students talked hypothetically about unjust situations they may face and ways that they might positively and constructively deal with them, if they were to occur.

After giving the students the opportunity to question “Who benefits,” we wanted to encourage them to ask, “What if.” Moving forward, the class read selected poems from Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson (2014), coupled with an author study. Short (2003) writes, “Providing brief information about the background of authors and illustrators before reading aloud can raise children’s awareness about the significance of this frame in interpreting literature.”

Shannon stated, “The author study made it feel as if we had a guest speaker. The students read about what was what like for an African American to grow up in the 1960s.” Because Brown Girl Dreaming is Woodson’s memoir, students got a first-hand account of the social and political constructs to which the African American community has historically been relegated. At the same time, they were encouraged to imagine a better future. Shannon recognized the unique space this book provided for students to continue to grapple with the question, “what if?” The chapter that immediately caught both of our attention was entitled “The Revolution.”

The revolution is always going to be happening. I want to write this down that the revolution is like a merry-go-round, history always being made somewhere. And maybe for a short time, we’re part of that history.

The students wrote their own poetry in response to stanzas that struck them. One student drew from Woodson’s (2014) first poem in Brown Girl Dreaming, “too many people too many years / enslaved, then emancipated / but not free” (pp. 1-2) writing in her own poem, “stuck in a small cage / you’re set free / only to find out / you’re in a bigger fence.” Writing with and in response to the text prompted students to make deeper connections to their own lives. Slowly, they began to recognize that racism is part of a continuous cycle that must be broken, and that they have the ability to do so.

In the end, Shannon felt that, because the literature discussions were open and comfortable, students were able to trust each other enough to candidly express their experiences, feelings and thoughts. She said, “The most notable, yet least measureable change I saw within them was their willingness to talk about complicated issues in the world in a more confident and compassionate way.”

After the 2008 presidential election in the United States, much of the public opinion suggested that racism had declined. Many people believed that “a black man in the White House signified that we had finally matured as a nation, embraced diversity, and were forging a future of equality” (Kaplan, 2011, p. xi). However, just eight years later, people seriously questioned what was thought to be progress. The rhetoric leading up to surrounding the 2016 election presented an entirely different picture. What we learned is that fighting racism is a long and difficult battle. What we witnessed is the immense power of books to create safe spaces for our students to resist messages of today and imagine a “merry-go-round” where, “history is always being made” (Woodson, 2014, pp. 308-309).

Final Thoughts

For white teachers, or any teachers hoping to have open conversations about race in the classroom, honesty, openness and respect are key. Students need a space where they can say what they think and not shut down when others disagree. We came up with air symbols that meant, I agree/I wanted to say the same thing or I respectfully disagree, so students could also non-verbally share their thoughts and feelings. I always made sure to follow-up with students privately who chose to use air signs, to see if there was anything more they wanted to discuss.

~Shannon Clowes

African American Text-Set

Barack Obama: Son of Promise, Child of Hope. Nikki Grimes & Bryan Collier (2012). Ever since Barack Obama was young, Hope has lived inside him. Even as a boy, Barack knew he wasn’t quite like anybody else, but through his journeys he found the ability to listen to Hope and become what he was meant to be.

Brown Girl Dreaming. Jacqueline Woodson (2014). A novel in verse, the author shares what it was like to grow up as an African American in the 1960s and 1970s, living with the remnants of Jim Crow and her growing awareness of the Civil Rights Movement.

Busing Brewster. Richard Michelson & R. G. Roth (2010). Bused across town to a school in a white neighborhood of Boston in 1974, a young African-American boy named Brewster describes his first day in first grade.

Henry's Freedom Box. Ellen Levine & Kadir Nelson (2007). A fictionalized account of how in 1849 a Virginia slave, Henry "Box" Brown, escapes to freedom by shipping himself in a wooden crate from Richmond to Philadelphia.

I, Too, Am America. Brian Collier & Langston Hughes (2012). Presents the poem of Langston Hughes which highlights the courage and dignity of the African American Pullman porters in the early twentieth century.

Most Loved in All the World: A Story of Freedom. Tonya Cherie Hegamin & Cozbi A. Cabrera (2008). An authentic and powerful account of slavery and how a handmade quilt helps a little girl leave home for freedom.

A Place Where Hurricanes Happen. Renee Watson & Shandra Strickland. (2010). New Orleans is known as a place where hurricanes happen . . . but that’s just one side of the story. New Orleans friends Adrienne, Keesha, Michael, and Tommy take turns speaking in spare free verse.

Something Beautiful. Sharon Dennis Wyeth & Chris K. Soentpiet (1998). A young African-American girl, depressed/oppressed by the ugliness in her inner-city neighborhood, searches for "something beautiful," and finds it in the small details of her community.

Underground: Finding the Light to Freedom. Shane Evans (2011) Follows a family's journey toward freedom as they travel along the Underground Railroad.

When Marian Sang. Pam Munoz Ryan & Brian Selznick (2002). Marian Anderson is known for her historic concert at the Lincoln Memorial in 1939, which drew an integrated crowd of 75,000 people in pre-Civil Rights America.

References

Hess, D., & McAvoy, P. (2015). The political classroom: Evidence and ethics in democratic education. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kaplan, H. R. (2011). The myth of post-racial America: Searching for equality in the age of materialism. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education.

Kozol, J. (1991). Savage inequalities: Children in America's schools. New York, NY: HarperPerennial.

LaFleur, J. (2014). The opportunity gap: Peter Howell Elementary School. Retrieved from http://projects.propublica.org/schools/schools/40880000853

Lopez, I. H. (2000). Institutional racism: judicial conduct and a new theory of racial discrimination. The Yale Law Journal, 109( 8), 1806.

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1998). The reader, the text, the poem: The transactional theory of the literary work. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Short, K. (2003). Reading critically through global inquiry. WOW Stories, I(3). Retrieved from

http://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi3/2/

Short, K. (2009). Inquiry as a stance on curriculum. In S. Carber & S. Davidson, (Eds.), International Perspectives on Inquiry Learning. London: John Catt.

Tatum, E. (2015). Why don’t Black Lives Matter? New York Amsterdam News, 106(16), 12.

Worlds of Words. (n.d.). Language and Culture Book Kits & Global Story Boxes. Retrieved from http://wowlit.org/links/language-and-culture-resource-kits/

Children’s Literature Cited

Braswell, K., Dent, J., & Anderson, J. (2015). Daddy, there's a noise outside. Atlanta: Black Rose Mediaworks.

Cohn, D., & Delgado, F. (2002). ¡Sí, se puede!/Yes, we can!: Janitor strike in L.A. El Paso, TX: Cinco Puntos.

Coleman, E., & Geter, T. (1996). White socks only. New York: Albert Whitman.

Evans, S. (2012). We march. New York: Square Fish.

Freedman, R., & Malone, P. (2012). The Boston Tea Party. New York: Holiday House.

Krull, K., & Morales, Y. (2013). Harvesting hope: The story of Cesar Chavez. Columbus, OH: Zaner-Bloser.

Markel, M., Sweet, M., & Zegar, R. (2013). Brave girl: Clara and the Shirtwaist Makers' Strike of 1909. New York: Balzer Bray.

McGinty, A. B., & Gonzalez, T. (2013). Gandhi: A march to the sea. Las Vegas, NV: Amazon.

Pinkney, A. D., & Taylor, M. L. (2010). Sit-in: How four friends stood up by sitting down. New York: Little, Brown.

Warren, S. E., & Casilla, R. (2012). Dolores Huerta: A hero to migrant workers. New York: Marshall Cavendish.

Woodson, J. (2014). Brown girl dreaming. New York: Nancy Paulsen Books.

Desiree Cueto is an Assistant Professor of Education at Western Washington University, Bellingham, Washington.

Shannon Clowes taught fifth grade at Peter Howell Elementary School in Tucson, Arizona before moving to Chicago to take a position as a sixth grade teacher at Alain Locke Charter School.

WOW Stories, Volume V, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/v5-i2.