Download as PDF

Seeing Me: Confronting Real and Symbolic Borders through Stories

By Desiree Cueto and Julia Hillman

Some agreed with the fisherman, but others were louder…And they built a great wall all around the island, with watchtowers from which they could search the sea for signs of rafts, and shoot down passing seagulls and cormorants so that no one would ever find their island again.

~Armin Greder (2008)

Arabic-Speaking Countries and Cultures Language Kit

Immigration has historically been a “hot-button” issue. Nearly every group that has arrived in the United States, including those from Italy, Ireland, Poland and China, has been met with some resistance. Today is no different; immigration remains an issue brimming with controversy. What is different, however, is the way in which this issue has come to represent the extreme tensions between left wing and right wing politics, and how it is increasingly linked to racial, ethnic and religious intolerance. Current immigration debates have concentrated on building walls across the United States-Mexico border and on the mass deportation of the nearly 11 million undocumented immigrants, including children (Goo, 2015). Descriptions of radical terrorists have been used to represent every member of the Islamic faith. Suggestions have also been made to bar all Muslims from entering this country. Still, many people see America as a land built by immigrants and the Statue of Liberty as a beacon of hope. As questions over whose voices will be louder loom in the air, teachers wonder how to decrease fear and inspire hope in the students they serve.

This vignette extends an invitation into Julia Hillman’s fourth/fifth grade English Language Development classroom. When students in this class saw familiar experiences reflected in literature, they made deep connections, kept the books close and shared them with others. This is illustrated in the following response:

“Ms. Hillman, look! This book shows people like me.” A girl, who had recently come to the United States from Afghanistan, held up Coming to America: A Muslim Family’s Story (Wolf, 2003). She patted the seat next to her and invited her teacher and fellow classmates to take a look. “This is my story,” she said.

Over the course of the unit, many students in Julia’s class made similar connections. As a whole, the students evolved into engaged readers, writers and proud authors of their own immigration stories.

Julia’s Story—Transforming Practice

For Julia, inspiration to start this work came after she read “Building on Windows and Mirrors: Encouraging the Disruption of ‘Single Stories’ Through Children’s Literature” by Christina M. Tschida, Caitlin L. Ryan and Anne Swenson Ticknor (2014). In the article, the authors highlight research on the importance of providing students with “mirrors” and “windows” that reflect their own experiences and also open their eyes to the experiences of others. Julia admits that prior to engaging in this work, she was not certain that any of this was possible—at least not in a public school setting. Like many teachers, she felt stifled by the rigorous testing and data (test scores) collection that had been driving instruction since No Child Left Behind (2002). She shared,

Teaching and learning were beginning to feel meaningless. I started to question the purpose of education. It wasn’t until I learned new strategies and started using multicultural and global books to develop text sets that I became excited again. This felt like a natural way to teach.

Throughout the eight years she has taught at Blenman Elementary School, Julia has welcomed students from the Marshall Islands, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Iran, Nepal, India, Japan, China, Vietnam, Ethiopia, Congo, and Mexico, among other countries. There are currently 7 different languages spoken within her classroom including: Swahili, Farsi, Arabic, Spanish, Marshallese, Nepalese, and English. She says that the opportunity to work with students from diverse countries and cultures has provided her with invaluable experience. Her students are, by far, the greatest inspiration for her work.

Worried about the impact that public discourse might have on her students, Julia decided to join fellow teacher, Amy Edwards, to write a unit that centered on immigration under the broader theme of Forced Journeys. Initially, the work felt impossible. One tension that Julia felt was whether an expansive enough collection of books to represent all of her students’ experiences actually existed. To remedy this, Julia applied for a grant to buy additional titles that had not been ordered through the district’s purchase. She shared,

A student once asked why I don’t have any books on Marshallese culture, so I explained that when we ordered books there weren’t any, but that I would look for some or he could write some for this class.

Another problem Julia faced had to do with time. In Arizona, English Language Development classes like the one she teaches are required to follow a 4-hour language block. To solve this issue, Julia integrated literature into every aspect of her teaching. Because the students were deeply interested, they wanted to spend time reading and talking about the books. Their enthusiasm carried over and across disciplines. Julia found that a real transformation occurred when the students were immersed in the literature and invited to participate in variety of engagements around the books.

They became active and interactive participants in their own learning. I saw the excitement in their eyes every time I set out the books. I also saw it when I read aloud to them. They huddled close to take in the story. Almost immediately, students made connections and shared their reactions to the books. They were really eager to share the books they were reading independently as well.

Through multiple transactions with the texts, students began to see for themselves what literature had to offer them. As time went on, the books and discussions surrounding them inspired students to draw, write, create PowerPoints and other presentations. They also engaged in inquiries prompted by their own connections and tensions. Julia says that it was upon witnessing this transformation in her students that her own teaching practices were forever changed.

Forced Journeys

During our workshop sessions, fifth grade teachers decided that the enduring understanding for their second unit would be: Journeys are movements along a pathway (e.g. physical, emotional, or cultural). Under the broader theme of Forced Journeys, teachers wanted to explore issues such as immigration, detainment, deportation and refugees’ experiences. Considering both the framework for intercultural understanding and the Inquiry Cycle, Julia intuited that her students would easily make connections to these issues. Starting with immigration, she arranged a text set on the back counter in her classroom and asked students to join her in surveying the images across a number of books. Several books, In the New World: A Family in Two Centuries by Christ Holtei (2015), Have a Good Day Café by Frances and Ginger Park (2008), Fiona’s Lace by Patricia Polacco (2014) and Home at Last by Susan Middleton Elya (2006), focused on family journeys. Others like, I’m New Here by Anne Sibley O’Brien (2015), My Two Blankets by Irena Kobald (2015) and Here I Am by Patti Kim (2015) featured children who struggled to adjust to life at a new school and in a new culture without losing their sense of identity. What was consistent across the set of books was their ability to capture the humanity of those who have moved from one country to another. In this way, the books served as a counter-narrative to negative representations of immigrants portrayed in some media outlets.

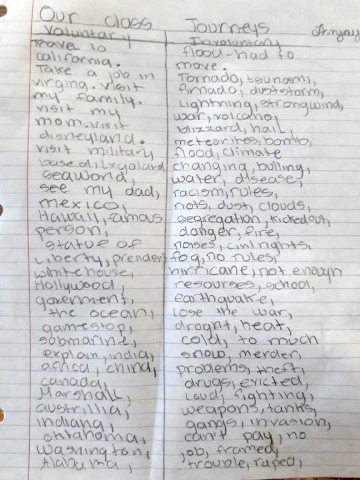

As she turned the pages of each book, Julia commented that many of the students in the class had been on journeys similar to those depicted in the books. The students nodded in agreement and she acknowledged the various countries from which they had come—Nepal, Congo, Mexico, and so on. She also talked about how they might have travelled—by boat or plane or foot. Then she paused, allowing students to think about the enduring understanding. She asked, “What is a journey?” and “What kinds of journeys do you know about?” Students shared based on their own experiences and Julia webbed their ideas on a large piece of chart paper with the word JOURNEY written in the center.

Enduring Understanding:

Journeys are movements along a pathway (e.g. physical, emotional, or cultural).

Essential Questions:

What is a journey? What do you know about journeys?

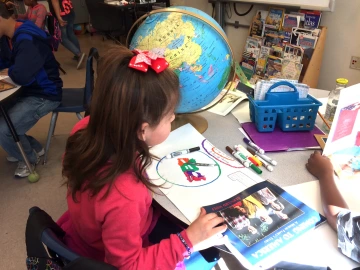

After writing the enduring understanding and essential questions on the board, Julia invited students to select books to which they felt a special connection, or books that reflected their personal experiences in some way. Students spent a good amount of time browsing the books and commenting to one another about the connections they were making. Julia documented the ways in which they selected their books. Some chose books that had familiar images. For example, several students selected One Green Apple by Eve Bunting and Ted Lewin (2006). On the cover, a young girl is wearing a hijab. They also chose books that contained familiar languages. Two boys, who emigrated from Mexico, opted to read My Diary from Here to There: Mi diario de aqui hasta alla by Amanda Irma Perez (2002). The boys shared the book, alternating pages and languages as they read aloud. Still others gravitated toward books featured in the opening engagement, like Two White Rabbits, a Mexican migrant story by Jairo Buitrago (2015) and Inside Out and Back Again by Thanhha Lai (2011), which explored the immigration experience of a family fleeing Vietnam.

Once students selected and read their books, they were given time to engage in an adapted version of the Book Pass engagement (Kaser, 2012). For the purposes of this lesson, Julia wanted to provide students with exposure to a range of immigration stories and also allow them to talk about their own experiences in relation to the books. She wrote the following prompts on the board:

- This book is about (book summary)

- This book reminds me of (something in your life)

- You may find it interesting to know (something the book made you think about)

Throughout this engagement, students shared a great deal of excitement, connected the stories to personal experiences they each wanted to share and explored topics of interest to them. Julia observed as one group of students made an intentional decision to examine how closely the books reflected their own experiences. The following is a conversation that occurred when one student passed the book, Name Jar.

Student 1: In this book the girl wants to change her name. Well she’s thinking about it. Has anyone ever wanted to change your name?

Student 2: I have.

Student 1. Why?

Student 2. Because no one could say it right. People, like, they don’t even try.

Student 3. I never wanted to do that, but I wanted to change other things. Like I wanted to change my clothes.

Student 2. You wanted to change your clothes?

Student 3. Yes. Cause if you wear this [pointing to the hijab on the cover of One Green Apple (Bunting, 2006), they look at you strange.

Student 2. They look at you strange for everything...

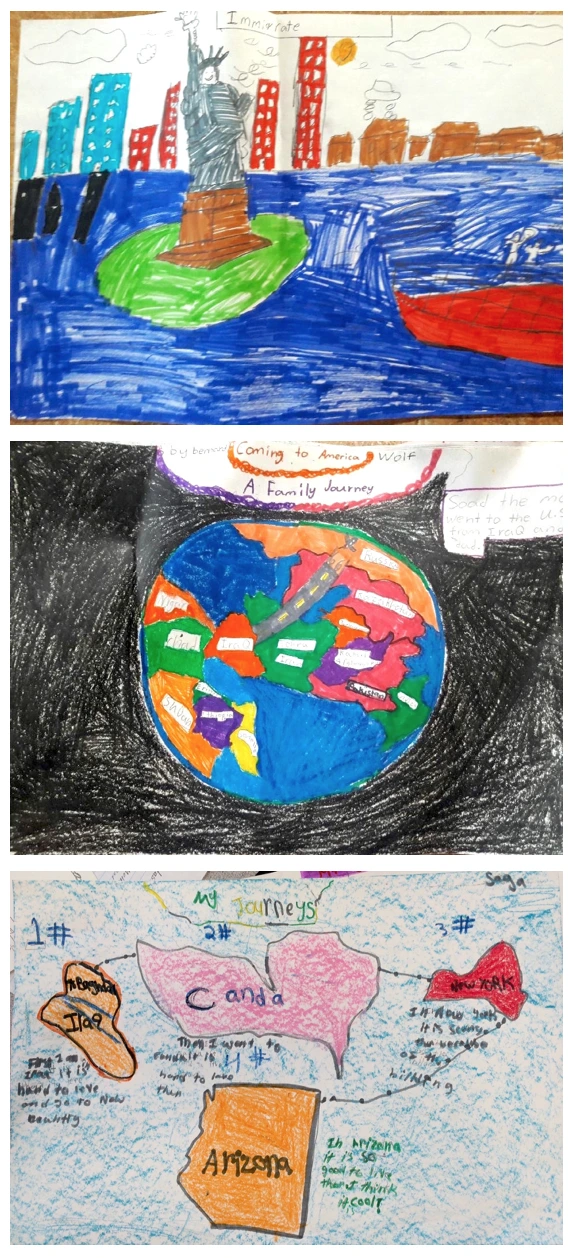

As the reading block came to a close, Julia informed students that they would be creating a Life Journey Map to reflect their own experiences as part of that day’s writing block. She shared an example of her own life journey map, but told students that all of the maps would look different. She instructed them to represent their lives in creative ways on the life journey map. They could choose to represent their lives literally or conceptually. Students were also told that the maps could be a timeline, bar graph, line graph, highway, garden, iceberg or any other creative way to represent the journey they are on. She told them that they would share these maps with other students in class when they were finished. Below are some of the maps the students created.

Engaging with Complexity

Essential Questions

- What are the causes and effects of forced journeys?

- How are forced journeys similar to and different from one another?

The next time I visited Julia’s classroom, the students were engaging in a strategy that Kathy Short developed called, “Comparing to Understand” in which students search for similarities and differences between cultural communities and for the reasons behind those differences. Julia and I talked about how she might use this strategy to help students think about differences between the immigration stories they had previously read, and the stories of those who had been on forced journeys (refugees, detainees and deportees). Julia intuited that the Forced Journeys theme might be difficult for some students, but she also understood the importance of allowing them to grapple with the complexity of their experiences. Of all the schools in the district, Blenman Elementary School and its feeder pattern to Doolen Middle School and Catalina Magnet High serve the highest number of international students and those who have refugee status. According to Tucson Weekly, “These schools are safe havens, mini-societies where all the students get nurturing, mentoring and guidance to adapt to and appreciate difference” (Bustamante, 2009). Julia wanted to be conscious and intentional in the way she went about exploring differences. More than anything, she wanted students to leave the engagement feeling empowered.

To start the lesson, Julia explained that sometimes we don’t have choices in life, and we are forced to do things we don’t want to do. She asked the students to give examples of things they have been forced to do. They came up with examples such as going to bed early, doing homework, and moving to a new country, among others. Julia held up Brothers in Hope by Mary Williams (2005), which tells the story of the Lost Boys of Sudan. Many of these young men ended up in Tucson and are currently living in the same central neighborhood as Julia’s students.

The next book Julia added to the text set was Anna & Solomon by Elaine Snyder (2014), a love story about a young Jewish couple forced to flee Russia in 1897. The third addition was Landed by Milly Lee (2006), about a young Chinese man eager to arrive in America, only to be detained at Angel Island until he is able to pass an oral language examination. Finally, she presented the students with Mama’s Nightingale by Edwidge Danticat (2015). This book portrays a young girl’s deep concern about her mother who has been taken away to a detention center and is facing deportation to back to Haiti. Julia gave each group in her class one book to examine closely. After studying the books, the students were instructed to have one representative from each group to add new thinking to the class’s Journey Web. Students contributed words like:

- Difficult

- Harsh

- War

- Sad

- Afraid

- Homeless

- Alone

In small groups, students were more expressive about their observations of the books, and began connecting what they read in the new books to what was portrayed in the immigration text set. They used the words “stereotypes,” “racism,” “injustices” and “status” to discuss their connections between the two sets of books. One student also referred to book characters as “invisible” because “they don’t speak English.” As Julia listened to interactions between her students, she noted, “The students are very aware of what is happening to these characters. They are sensitive to their needs and feelings.” This conversation provided a segue into the Comparing to Learn Engagement. Julia had photocopied a page from Brothers in Hope (Williams, 2005) for each student. The caption below the page read: “Some of the boys were only five years old. The oldest boys were not more than fifteen. We were children, not used to caring for ourselves. Without our parents we were lost. We had to learn to take care of one another.” On another sheet of paper, she gave each student a photocopied image taken from Home at Last (Elya, 2006). The text on this page read: “That night, Papa asked, ‘Do you like school?’ ‘Yes, I like it.’ Her parents smiled. Mama made supper while Papa told them about his new job. Papa had to start with sweeping and cleanup work, unlike Uncle Luis, who had been at the factory longer and could run a machine.” The students worked independently to answer the questions outlined on the Comparing to Understand strategy sheet.

Global Thinking: Comparing to Understand

Intercultural understanding involves a willingness to engage with complexity by exploring both how we connect to people in a specific global context and how we value what makes each culture unique. Compare two groups of people engaged in a similar activity but in different cultural contexts with these questions:

Looking for connections and similarity

What are the connections across these two situations?

What about these two situations looks similar?

Looking for uniqueness and difference

What is unique about each situation?

What about these two situations looks different?

Asking deep questions

What deep questions or big ideas might help us understand what is going on?

What are possible reasons why these actions are occurring in each situation?

Going beyond

What questions do we still have?

What do we need to know more about to understand these situations?

How can we go beyond our current understandings?

After a time, Julia focused the students’ attention to the board, where she had written the questions across four panels. The students’ responses were as follows:

Connections and Similarities:

- They all came from another country

- They all came here (the United States)

- They are children

Uniqueness and Difference:

- The girl has parents

- The boys just have each other

- The boys are their own family

- The girl has a mother who cooks

- The girl has a father who works

- The boys have to work and cook for themselves

- The boys walked everywhere

- The girl (we think) came to America on a plane, car or bus

Asking Deep Questions:

- Where are the boys’ parents?

- Why does the girl’s dad have to sweep floor?

- Why did the boys leave their country? Was there a war?

- Why did the girl and her family leave their country?

- Did they want to stay in their country?

Going Beyond:

- The students decided that they wanted to know more about what happened to make each of the characters leave their home countries. Some students were familiar with the story of the Lost Boys, but they wanted to know more. Another issue that came up for students centered around war. They wanted to know why the fighting had occurred in Sudan. To find out more, they made plans to interview people and to Google, “War in Sudan.”

Julia continued teaching this unit into the third quarter. Whenever I checked in with her, she shared something new and exciting that happened in her classroom. Her stories often reminded me of words of wisdom shared by Jerry Harste and Kathy Short (1996), "Classrooms are not here to silence children, but to hear from them. In a democracy schools are not here to marginalize some children, but to hear all voices" (p. 17). The most powerful events in Julia’s classroom centered on students writing and telling their own stories. Indeed, the books had served as a source of inspiration. In the process of articulating what they read in books, students came to develop and recognize their own voices. They realized that there was power in sharing their stories with one another and with the world.

Final Thoughts

More than anything, I wanted my students to feel empowered. I wanted them to know that they have rights and they can use their voices to fight for their rights. Our unit—the books we read and the stories they wrote—became a way to speak truth to power.

~Julia Hillman

References

Bustamante, M. (2009, April 11) Refugees’ diversity celebrated at midtown schools. Tucson Citizen. Retrieved from http://tucsoncitizen.com/morgue/2009/04/11/114128-refugees-diversity-celebrated-at-midtown-schools.

Goo, S. K. (2015, August 24). What Americans want to do about illegal immigration. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/08/24/what-americans-want-to-do-about-illegal-immigration.

Short, K. G., Burke, C. L., & Harste, J. C. (1996). Creating classrooms for authors and inquirers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Tschida, C. M., Ryan, C. L., & Ticker, A. S. (2014). Building on windows and mirrors: Encouraging the disruption of single stories through children's literature. Journal of Children's Literature 40(1), 28-39.

Worlds of Words. (n.d.). Language and Culture Book Kits & Global Story Boxes.

Children’s Literature Cited

Buitrago, J., Amado, E., & Yockteng, R. (2015). Two white rabbits. Toronto: Groundwood.

Bunting, E., & Lewin, T. (2006). One green apple. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Danticat, E., & Staub, L. (2015). Mama's nightingale: A story of immigration and separation. New York: Dial.

Elya, S. M., & Dávalos, F. (2013). Home at last. Columbus, OH: Zaner-Bloser.

Greder, A. (2008). The island. Crows Nest, NSW, Australia: Allen & Unwin.

Kim, P., & Sánchez, S. (2015). Here I am. London: Curious Fox.

Kobald, I., & Blackwood, F. (. (2015). My two blankets. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Lai, T. (2011). Inside out and back again. New York: Harper Collins.

Lee, M., & Choi, Y. (2006). Landed. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux.

O'Brien, A. S., Corzo, F., Livier, R., Ocampo, R. D., & Delawari, A. (2015). I'm new here. Watertown, MA: Charlesbridge.

Park, F., Park, G., & Potter, K. (2005). The have a good day cafe. New York: Lee & Low.

Perez, I. & Gonzalez, M.C. (2013). My diary from here to there: Mi diario de aqui hasta alla. (2009). Paradise, CA: Paw Prints.

Polacco, P. (2014). Fiona's lace. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Raidt, G., Holtei, C., & Woofter, S. (2015). In the new world: A family in two centuries. Watertown, MA: Charlesbridge.

Snyder, E., & Bliss, H. (2014). Anna & Solomon. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux.

Williams, M., & Christie, R. G. (2007). Brothers in hope: The story of the Lost Boys of Sudan. New York: Lee & Low.

Desiree Cueto is an Assistant Professor of Education at Western Washington University, Bellingham, Washington.

Julia Hillman teaches forth and fifth grade English Language Learners at Blenman Elementary School, Tucson, Arizona.

WOW Stories, Volume V, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/v5-i2.