Inquiring about Language through Dual Language Picturebooks: A Case Study

By Dorea Kleker, Kathy G. Short, and Nicola Daly

It is the first session of the Spring 2020 Global Cultures afterschool club. Safita, an inquisitive fifth grader, enters the library and eagerly sits down at a table to browse a collection of dual language picturebooks that combine English with a range of languages. She settles in with several books, placing post-its on places she finds interesting. After browsing, Safita selects Naupaka (Beamer, 2008), written in Hawaiian and English, as her favorite to share. She gives a detailed summary of the book, informing her peers that "it looks like a longer read because of the Hawaiian but it's superfast" because she had read only the English text in the book. Nicola informs the group that all of the books they browsed contain more than one language. While other children flip back through the pages of the books to locate the languages other than English, Safita goes a step further, using her knowledge of English phonology to attempt to quietly read the Hawaiian sections that she had previously skipped. Her immediate attention to an unfamiliar language was an inquiry about the pronunciation of that language and a willingness to take a risk. Later that day, as children compile a list of the languages they have heard about, Safita adds Hawaiian.

Safita is a curious fifth grader who arrived each week at our afterschool Global Cultures Club eager to learn and enthusiastic to share her knowledge and discoveries. In one of the first club sessions she described herself as "mostly North American and Mexican" with a "little part" Scottish who lived in an English dominant home. While her mother and grandparents speak Spanish, Safita shared, "I can't necessarily understand Spanish, but I know a few words".

This article follows Safita over the course of six weeks as she engaged with dual language picturebooks to develop language awareness and inquire about how these languages are used in books, her life, and the world around her. We selected Safita as a case study because she often shared her theories out loud as she talked her way into understanding, giving us access to her in-process thinking. Through this case study, we argue that dual language picturebooks provide a unique opportunity for children to explore their understandings and challenge their beliefs about language and language diversity.

Our Teaching Context

The Global Cultures Club began in Spring 2019 at a public magnet elementary school in a Latinx neighborhood in Tucson, Arizona. Dorea and Kathy started this club as a space to engage third to fifth-grade students in inquiries around global cultures, avoiding the pitfalls of only exploring easily observable aspects of these cultures--food, fashion, folklore, festivals, and famous people—through making connections between these aspects and deeper cultural values. The school has an active after school program with a range of options in which children can participate. Each semester, both paper and electronic invitations to the Global Cultures Club were sent home with families and all children who applied were invited to participate free of charge with class sizes ranging between 5-12 children.

In the spring of 2020, Nicola, a Fulbright scholar from New Zealand, joined our team and we shifted from a broad exploration of global cultures to a specific focus on language exploration using dual language picturebooks. Our goal was not to use these books to teach children specific languages; rather, we were interested in how children would engage with invitations around dual language picturebooks to inquire about language and develop language awareness.

Dual language picturebooks combine two or more languages in three ways:

- interlingual (one language dominates with words and/or phrases from another language interwoven throughout, often in dialogue)

- bilingual (entire text is presented fully in two languages, either on the same page, on facing pages, or in different sections of a book)

- dual version (book published as two separate versions featuring the same cover, design, illustrations, and layout but different languages)

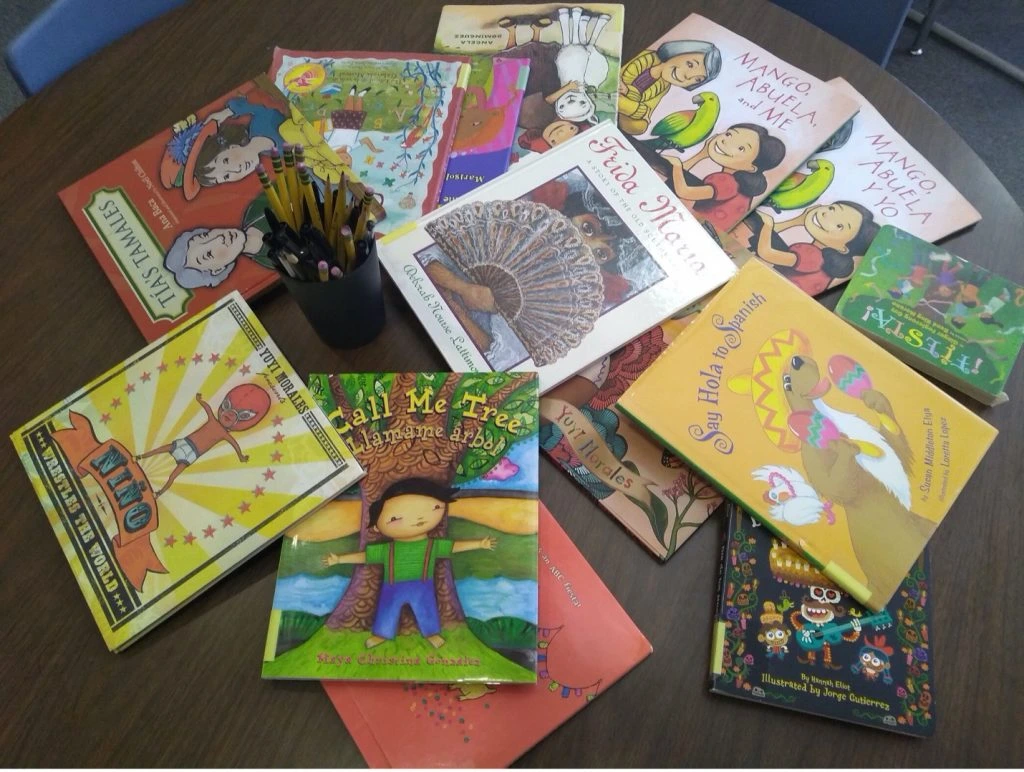

The club met once a week after school for 90 minutes in the school library. Each of the six sessions were built around a specific language focus (Spanish, Māori, or Indigenous languages spoken in the U.S.) and followed a similar format. Sessions began with time for children to browse dual language picturebooks related to that week's focus. During this time, children could engage with the books in any way they chose and regularly used post-it notes or large pieces of chart paper to note their connections and wonderings. Immediately following browsing, children shared their favorite books with the whole group, why they selected these, and any interesting observations. Sessions always included a read aloud of a dual language picturebook and a guided invitation that engaged children with the featured languages. Each session ended with children recording something they learned and something they were wondering about in their journals.

Inquiry is a collaborative process of connecting to and reaching beyond current understandings to explore tensions significant to learners (Short, 2009). As we analyzed our curriculum plans, field notes, and children's responses from the sessions, we realized that we could use an adapted inquiry cycle framework (Short & Harste, 1996) to describe the different opportunities that dual language picturebooks provided for the children within our club.

Connections to the life experiences and understandings of learners were our starting point of inquiry. Experiences that immersed children in exploring dual language picturebooks added to their life experiences from which they could build connections for a close study of these books. These invitations for close study after read-alouds expanded their knowledge, experiences, and perspectives through guided inquiry in that we determined a focus around which children asked questions to examine these books. Some of these invitations were demonstrations by teachers or children of strategies to use in reading and making sense of the languages in dual language picturebooks. As children expanded their understandings, they posed problems or tensions that were significant and compelling to pursue through inquiry explorations of the books. They also needed time to pull back and engage in reflections on their learning, to attend to difference about what was new or unlike what they already knew.

As children engaged with dual language picturebooks within this inquiry cycle, we particularly noted the active engagement of Safita and decided to use her language inquiries to build a case study. Safita often talked out loud as she went about her inquiries and so provided access to her thinking processes. This case study examines both what she explored related to language and how she went about her inquiries.

Safita as a Language Inquirer

In the first session, after children shared the books they had browsed and brainstormed the names of languages they knew, Nicola brought out a world map and asked children where they believed the languages they knew might belong. While some children immediately begin placing post-its with their languages on the map, Safita took her time; she examined the map and looked closely at the names of countries to confirm the languages she thought she knew as well as to play with the possibilities of new ones, "I don't know Egyptian, I don't know Canadian, I don't know Saudi Arabian". She then wondered where Swahili was, a language encountered in Lala Salama (MacLachlan, 2011), a book she had browsed earlier in the day. Kathy reminded her that the book takes place in Tanzania and together they located this country on the map.

Rather than top-down lessons about languages and where they are located, guided invitations such as these were intentionally planned so that open discussion and conversations became the central focus. It was this talk about language—to both herself and with others—that allowed us to see Safita's strategies for making sense of language. She used her personal connection to the languages she knew to explore other language possibilities, bringing in books she had browsed to pursue inquiries about the names of languages and where they are located.

Exploring Language Use in Picturebooks

In week 2, Spanish/English dual language picturebooks were set out for browsing. After browsing, Safita chose to share Rubia and the Three Osos (Elya, 2010) and Clara and the Curandera (Brown, 2011). This time she incorporated her observations about the presence of two languages into her description, telling us, "One is a mix of English and Spanish and the other is in two languages, English and Spanish". When Nicola asked her to say more about how each of her books uses language differently, she replied, "This one kind of just mixes Spanish in...like it uses Spanish words in English, and this is in both languages. It'll have one page with English and then with Spanish". When Nicola wondered aloud why the books might be made like this way, Safita suggested, "because they think that if some people speak Spanish, they can mix Spanish in a bit with English and the other one is if you only know Spanish and they only know English". Nicola drew upon Safita's observations about the use of multiple languages in picturebooks and gently invited her into a deeper study and consideration of author intent.

As the weeks progressed and children continued to browse and explore picturebooks in different languages, Safita remained enthusiastic in sharing her discoveries with others. In addition to providing detailed retellings, she also routinely included what she noticed about the ways languages are used within books. In a session focused on Indigenous languages spoken in the U.S., such as Cherokee, Hopi, and Navajo, Sarita shared a book, offering her usual detailed retelling, and then concluded with an analysis of language order in the book, "The other language is in Navajo. They put Navajo on top and English on the bottom". When Nicola asked her why the languages might be in that order, she replied, "It's a Navajo story. The most related language comes first". Safita shared her belief that Navajo came first because this book was written for Navajo children who could read that language and therefore was the most important language, in contrast to the majority of bilingual books she had explored in which English comes first.

A few minutes later, when a child shared a book featuring three languages (Inuktituk in script, Inuktituk in Latin script and English), Safita used her developing language awareness and understandings of decisions about language placement in books to offer yet another interpretation, "I noticed that it has the symbols first, then the sounds second, and the English last". When asked by Nicola why this might be the case, Safita continued to build on her previous analysis adding, "It's the most important to the least important. English is the least important, even though it's the language everybody knows". Safita demonstrated her knowledge of the societal dominance of English, noting that English in this Indigenous book was the least important for the audience, "even though it's the language everybody knows". These open spaces to talk about and explore language in the context of dual language picture books--both independently and alongside others--allowed us to see what Safita was making sense of and how she was doing it.

Trying Out New Languages

At the beginning of each session we provided a wide range of dual language picturebooks for browsing in order to see what children would find interesting and build from these, not to guide children to a specific observation. In two sessions, we drew from children's noticings about the presence of multiple languages in the books to conduct our read alouds of bilingual picturebooks in both languages; we wanted to invite children to consider the impact of reading/hearing two languages in different orders. This allowed children to experience hearing a familiar language first because both books presented the English language text first, and then to immediately experience hearing the same story in another language. For example, Kathy and Nicola read My Colors, My World/Mis colores, mi mundo (Gonzalez, 2007) with Nicola reading the English text and Kathy reading the Spanish text. Once this was done, we read the book again, this time in Spanish first and English second. Contrary to our expectations, children appeared to listen more intently to Spanish (less familiar language) when it was read first rather than second. Safita said that because she knew some Spanish, she liked to listen to Spanish first to see how much she understood and then check herself when the English was read second.

Each session of the Global Cultures Club included a read aloud of a dual language picturebook with demonstrations of how readers might approach books containing languages that are unfamiliar to them by using illustrations, context clues and pronunciation guides. Safita began to use these as she shared her favorite books from browsing. In one sharing, she showed a page to the group and pointed out how the text was written in English with a few Spanish words thrown in. She proceeded to read a line aloud to illustrate her point, paying careful attention to the Spanish pronunciation. Later, in a session focused on dual language picturebooks featuring Māori, Safita shared Seven Stars of Matariki (Rolleston-Cummins, 2008), intentionally using Māori words and attending to careful pronunciation throughout her retellings. As noted in the opening vignette, Safita was curious about and quietly attempted to read the Hawaiian to herself in our first session. After a few sessions of guided invitations, demonstrations, and book browsings about and around various languages, she was eager to make her language attempts more public. We noticed that it became important to Safita to not only notice the presence of other languages in the books she was browsing, but also to attempt to use them as often and as accurately as possible in her sharing and discussion of them.

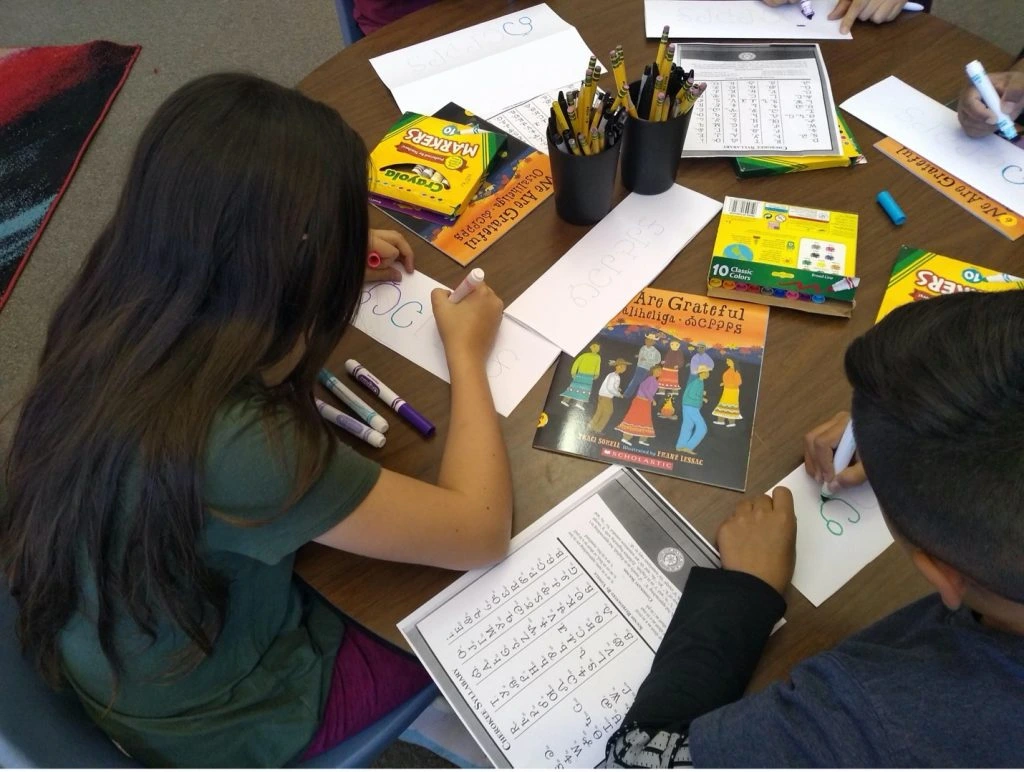

As a guided invitation designed to have children engage with a language that neither the children nor we were familiar with, Nicola introduced We are Grateful: Otsilaheliga (Sorell, 2018) an interlingual book written in Cherokee and English and the children quickly took note of the Cherokee on the cover. The other students guessed this to be a "secret language" and Safita wondered if "those marks are symbols?" Nicola provided additional context, telling them that Cherokee has its own unique way of writing. She pointed out the title written in English 'We are Grateful', in Cherokee spelled using the Latin alphabet, 'Otsaliheliga', and in the Cherokee writing system. She then read aloud the book, in which post-its had been used to cover the English translation for the Cherokee words in the English text. Nicola was able to read aloud the Cherokee words because the book provided a pronunciation key at the bottom of each page. As she read, children guessed the meaning of the Cherokee words using cues from the visual and textual context. They could immediately check their guesses by removing the post-it.

After reading the book aloud, Nicola concluded by showing children the end page which contains the Cherokee syllabary. As children read the word "syllabary," Safita excitedly exclaimed, "it's like a syllable library!", building upon her previous noticing of symbols to create a different, more elaborate understanding of this unfamiliar orthography in which each symbol is a sound for a syllable. Nicola invited children to use the Cherokee syllabary to attempt to write their own names. Safita quickly noticed that the top row "looks like it's the vowels 'cause it's a, e, i, o, u". She added, "some of their letters look like normal letters, like the G and the D and the R and the T and the Y and the A". Safita worked alongside her peers, looking carefully at the chart and attempting to find the syllables that corresponded with those in her name.

As Safita looked for the /fi/ in her name without success she considered a previous engagement with a read aloud of The Marae Visit (Beyer & Wellington, 2019), a dual language Māori/English book. During this read aloud, a peer wondered about a particular word—whia—which led to a discussion about how the "wh" makes a /f/ in Maori. Safita pondered this as a possibility in Cherokee and searched for a close alternative in her syllabary chart. Safita continuously used intertextual connections from books, group discussions and her life to test out her hypotheses about new languages and how to use them.

Conclusion: Lessons from Safita

As we reflected on our experiences with dual language picturebooks in the afterschool club, we were impressed with Safita's interest in these books, her depth of insight about the books and languages, and her excitement in exploring new languages. Dual language books challenged her expectations of the format of picturebooks and her notions of which she could and could not read. Despite the presence of multiple languages in all the books, Safita did not initially see--or was unsure of--how to interact with them. A dedicated time to connect with the format and content of these books and the space to have open conversations about these allowed her to explore her inquiries and continue to draw upon these understandings in new contexts.

Safita's responses to and engagement with dual language picturebooks over the six weeks of the Global Cultures afterschool club offer important lessons to consider when using these books in classrooms: 1) picturebooks in languages that are familiar to children provide a good beginning point to encourage connections to their language resources; 2) children should have access to interlingual books that contain unfamiliar languages so they can develop strategies for how to engage with unfamiliar words and phrases in new languages; 3) time to browse books is essential as the anchor to provide a source of rich connections and possibilities for inquiry across other experiences; 4) a dedicated time for sharing self-selected books opens a space for children to reflect on their connections and wonderings and gives teachers insights into children's knowledge, inquiries, and misconceptions from which invitations can be created; and 5) teachers who read and work alongside children in spaces that are not dominated by teacher questions or highly directed activities create opportunities for informal talk with children and for placing themselves in the position of co-learners. This co-constructed talk provides teachers with deeper insights into children's thinking and inquiries.

Many children have a great deal of linguistic capital that comes from living in multilingual communities, families, and classrooms, even though they may be unaware of that knowledge. They also bring a joy to exploring new languages that is inspiring, almost as though language is a puzzle for them to solve, a perspective that differs from how many adults approach a new language. Dual language picturebooks provide a means for children like Safita to tap into and expand their linguistic capital and put them in the position of becoming language inquirers.

Children's Literature References

Beamer, N. (2008). Naupaka. (C. K. Loebel-Fried, illus.). Bishop Museum.

Beyer, R., & Wellington, L. (2019). The Marae visit. (N.S. Robinson, illus.). Duck Creek.

Brown, M. (2011). Clara and the curandera. (T. Muraida, illus.). Little Brown.

Elya, S. M. (2010). Rubia and the three Osos. (M. Sweet, illus.). Little Brown.

Gonzalez, M.C. (2007). My colors, my world/Mis colores, mi mundo. Children's Book Press.

MacLachlan, P. (2011). Lala Salama: A Tanzanian lullaby. (E. Zunan, illus.). Candlewick.

Rolleston-Cummins, T. (2008). Seven stars of Matariki. (N. S. Robinson, illus.). Huia.

Sorell, T. (2018). We are grateful/Otsilaheliga. (F. Lessac, illus.). Charlesbridge.

References

Short, K. (2009). Curriculum as inquiry. In S. Carber & S. Davidson, (Eds.). International perspectives on inquiry learning (pp. 11-26). John Catt.

Short, K.G., & Harste, J., with Burke, C. (1996). Creating classrooms for authors and inquirers. Heinemann.

Dorea Kleker is a Lecturer in Early Childhood Teacher Education at the University of Arizona. (ORCID https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4551-2945)

Kathy G. Short is a professor and endowed chair of global literature for children and adolescents at the University of Arizona, and Director of Worlds of Words, Center of Global Literacies and Literatures. (ORCID https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9431-366X)

Nicola Daly is an Associate Professor at the University of Waikato in Hamilton, New Zealand. (ORCID https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3548-0043)

© 2021 by Dorea Kleker, Kathy G. Short, and Nicola Daly

WOW Stories, Volume IX, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work by Dorea Kleker, Kathy G. Short, and Nicola Daly at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/volume-ix-issue-1/4.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551