"Who's Big Mama?" Building Community in Math through Story

By Amy Corp

My first years of teaching were in urban classrooms where children of color comprised the majority of the students. As a white, middle-class female, much of the culture was new and differed from my own. I immersed myself in the community and found a wealth of cultural capital and connections to integrate into my classroom. I tried my best to represent these connections through art on the wall, literature in the classroom library, family photos on students' lockers, and posters with inspirational quotations from famous African Americans. Years later, when working on my Ed.D., I thought about ways to capitalize on culture when teaching specific mathematics content. I knew how to create a culturally affirming classroom environment from my previous experiences, but I struggled with the idea of affirming culture in mathematics. The struggle was connecting the mathematics content and processes to culture. Traditionally I followed the district curriculum that taught concepts in isolation and asked students to apply their problem-solving skills on test-like word problems. None of this content connected to culture or students home lives. After reading and researching ideas, I decided to harness the wonderful power of stories.

Stories have a rich history for engaging students. In mathematics instruction, stories can introduce a concept, demonstrate mathematics in real life, or be utilized to practice a concept, skill, or problems from the story (Whitin & Whitin, 2004; Wilburne, Keat, & Napoli, 2011). Stories with African-American characters have been used to engage African-American children in language arts (Altieri, 1993; Heflin & Barksdale Ladd, 2001), literature, and social justice (Copenhaver, 2001; Tatum, 2006). However, there was no research on using culturally responsive (Gay, 2002) stories in mathematics. I wondered if using culturally responsive stories where the characters reflect the race and/or culture of students would affirm culture and potentially engage all students in mathematics. I had to find out by doing my own research.

A 12 Week Experiment

During my dissertation research, I had the privilege to work with Mrs. Daniels (pseudonym) and the children in her two third-grade mathematics classrooms. The semester before the study we explored how using stories that affirm a non-dominant culture would build community and teach mathematics. Mrs. Daniels and I had piloted the idea with three stories, all featuring non-white characters, and concluded that all students had enthusiastically engaged in the stories. They also seemed to have common understandings from the stories and worked together quite eagerly on the mathematical activities from the stories. We believed that the stories also gave students a space to talk about similarities and differences in culture and decided to test our idea with a full study.

Over the summer we vetted 12 stories using criteria from Heflin and Barksdale-Ladd (2001) for selecting high quality literature with African-American characters to mirror the dominant culture in the school. We also looked for stories that would resonate with students from lower SES homes. Next, we developed lessons to draw attention to the mathematics in each story and aligned them with state standards (similar to Common Core State Standards for Mathematics). In the fall, we implemented these lessons in Mrs. Daniels' two sections of mathematics. There were 42 students: 18 African American, 7 Latinx and 17 White. There were 25 females and 17 males all from low SES homes (WISD district records, 2013). One of the district and school goals was to increase student engagement in mathematics, especially with African-American students. As a result, I decided to observe all students and especially focus on the African-American students in Mrs. Daniels' classrooms.

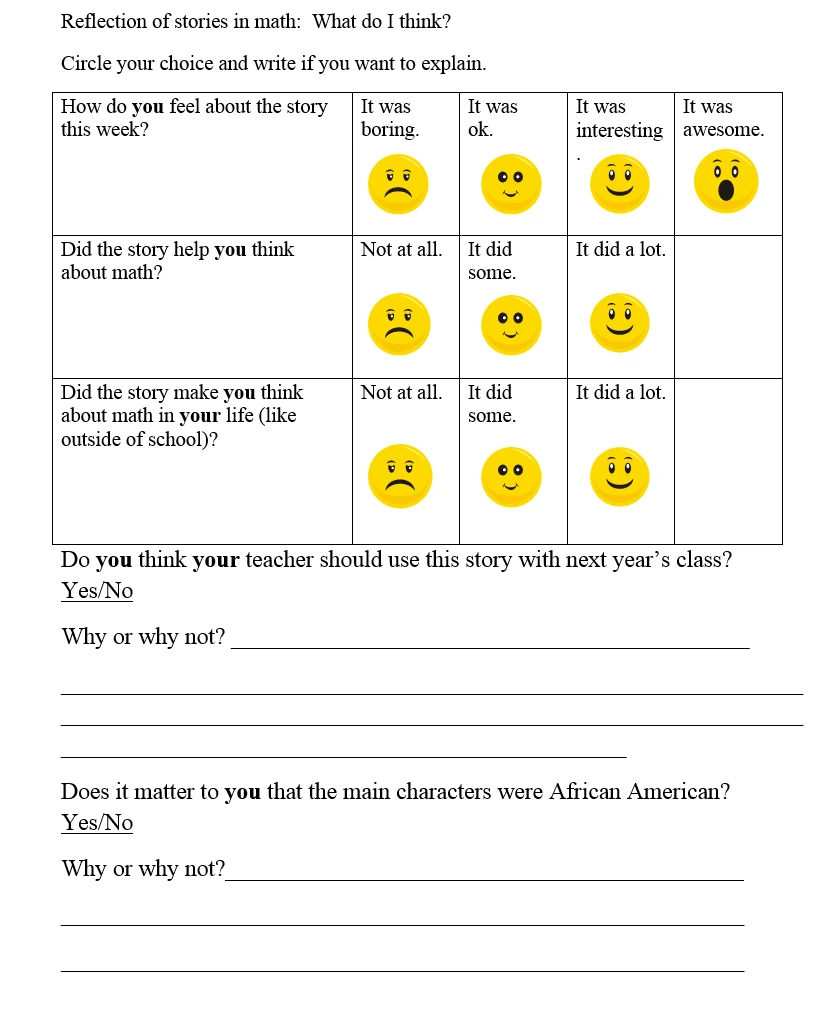

Each Wednesday Mrs. Daniels implemented one of the crafted lessons with students in each mathematics class in three distinct parts: reading the story, discussing the mathematical connections to the story, and facilitating mathematical activities or problems connected to the story. I sat to the side and scripted what I saw and heard during each lesson. All students filled out a reflection sheet at the end of each lesson. Students' responses to the reflection questions showed that they enjoyed the stories, and the stories helped them think about mathematics to varying degrees (Corp, 2017). The responses also showed that students gleaned social benefits while engaging in the lessons. For example, students made connections to each other and to the story through questions about food, vocabulary and other commonalities found in the stories. Additionally, students bonded around shared memories of lesson activities like tasting soup (described below). Mrs. Daniels sometimes heard them reminiscing about an activity or making connections to one of the stories during recess.

This vignette illustrates the mathematical engagement we experienced in this study. Just Right Stew (English, 1998) is the story of a secret kept by Big Mama (the matriarch and main character of the story), who cooks with love, and of the strong family bonds between members of the African-American culture. In our problem-solving portion of the lesson students connected mathematics to Big Mama's following the recipe with fractions and varied measurements of different ingredients, and to how the stew was dished out (subtraction or division). Students extended the math by thinking about who they would invite to such a celebration, and about purchasing the ingredients to create their own "just right stew." As you read our story imagine simmering broth and excited children awaiting a read aloud.

Our Story

As the first class ambled in the room, students noticed an aroma right away. Soon we heard comments like, "I'm hungry, what are we making?" and "That smells like my mom's chicken soup." As soon as the morning "business" was done, Mrs. Daniels called the students to sit criss-cross on the carpet in front of her. Students quickly got to the carpet and began to discuss the book she held as she waited for them to settle. "Just Right Stew, oh, we're gonna have stew?" commented one boy.

Mrs. Daniels invited students to share what they knew about stew or to predict what the story would be about with a partner for a few seconds. Several students said stew was like soup. Some students claimed it sounded like Carne Guisada (Mexican beef stew) and others commented about cooking with their grandma, mom, or aunt.

As Mrs. Daniels enthusiastically read the story aloud, I recorded students' behavior. Students interacted by acting out the story, talking to the characters, making comments about the characters or story plot, asking questions, reacting with laughter and/or surprise, and clapping loudly at the end. At the beginning of the story students all sat criss-cross but as the story continued many (especially those in the back) were up on their knees or leaning over toward the book. Body posture suggested that students were eager to learn Big Mama's secret ingredient for her stew and were highly entertained by the interaction of the women in the family, as well as the warm relationship between granddaughter and grandmother.

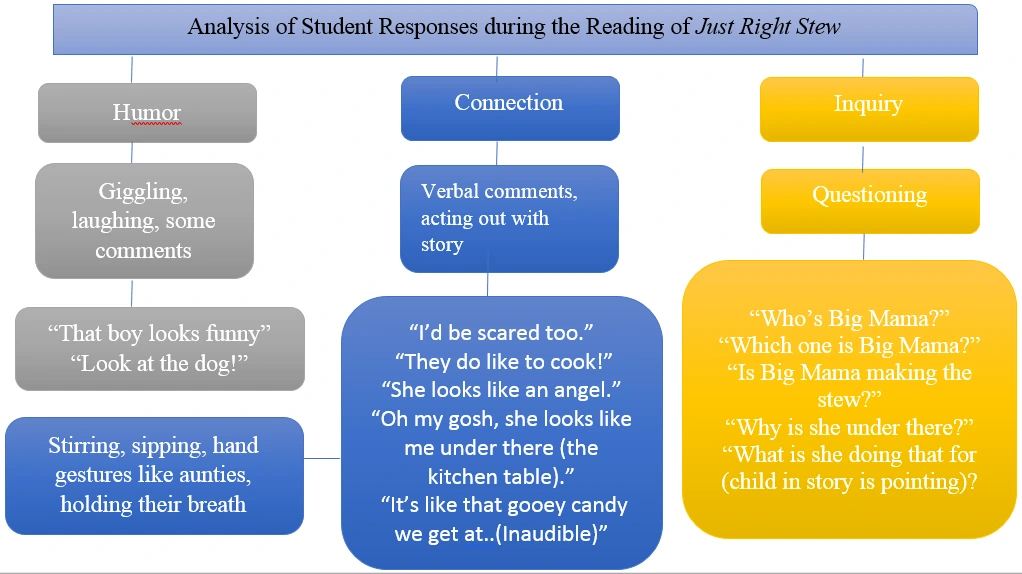

Analysis of my focus group observation data showed that 86.6% of students had eye contact on the story or the teacher at the beginning, middle, and end of the read aloud. Seventy-five percent of these students made comments or noises during the story. When analyzed, these comments were categorized as finding humor, making a connection, or inquiry (see Figure 1). Mrs. Daniels stated that these same students were not often interested or engaged in her mathematics class unless she called on them.

Figure 1. Themes that emerged from observing them during the reading of the story.

Discussion Time

When the clapping died down Mrs. Daniels asked, "What are some things in the story that go with our objective for this week?" The objective was written on the board: Solve one and two step problems using adding, subtracting, and/or multiplying, and dividing. Many hands shot up as she gave students time to think. When she called on students, most students commented on using addition and subtraction with the amounts of certain ingredients going into the stew. Others mentioned adding to find out the number of guests coming to the party. Several students mentioned dividing the stew into portions for the guests. A student connected the story to money, "You have to buy the ingredients, that's adding and subtracting." Another student mentioned, "Well, there are probably fractions in the recipe." These comments showed us that students identified some of the mathematical thinking that happens in the real-life situations of food preparation and service at a family gathering. Students would soon solve some of these very problems during their practice time.

Practice Time with Activities and Problems from the Story

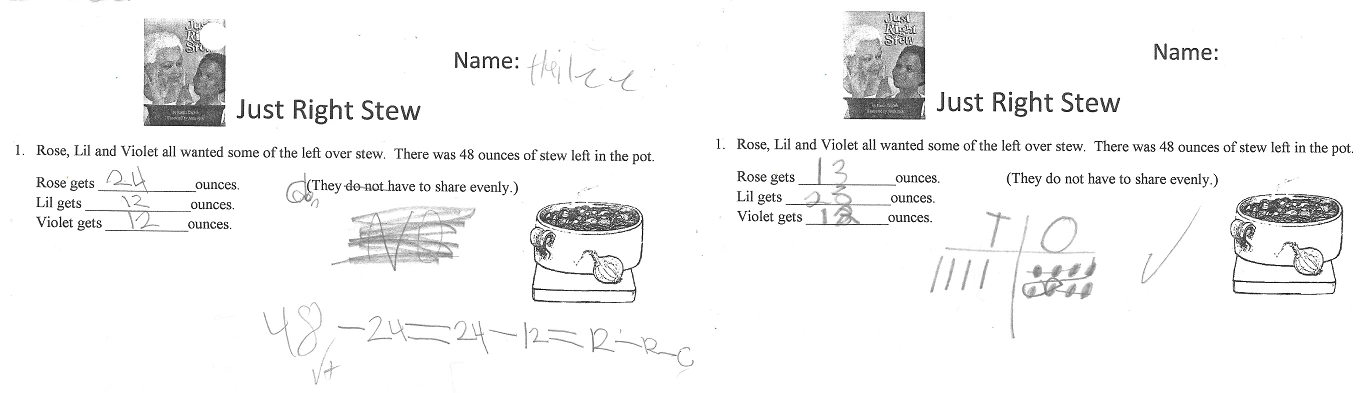

Mrs. Daniels complimented students on their thinking about the use of mathematics to plan and create recipes, meals, parties, etc. for families. Then, with a few instructions from Mrs. Daniels, students received their activity page and smiled as they went to their tables to work. In developing the activity pages, Mrs. Daniels and I took care to scaffold the problems from review of simple addition to more complex reasoning and operations. As I observed students working on different parts of the activity, I noticed students talking about the problems. One of the problems required students to divide the leftover stew (See Figure 2). Some students used three numbers that added up to the total amount, some drew a picture, and one student said she used the number line on the wall. The example below shows a student decomposing the amount using base ten.

Figure 2. Problem 1 from student work: division of the leftover stew.

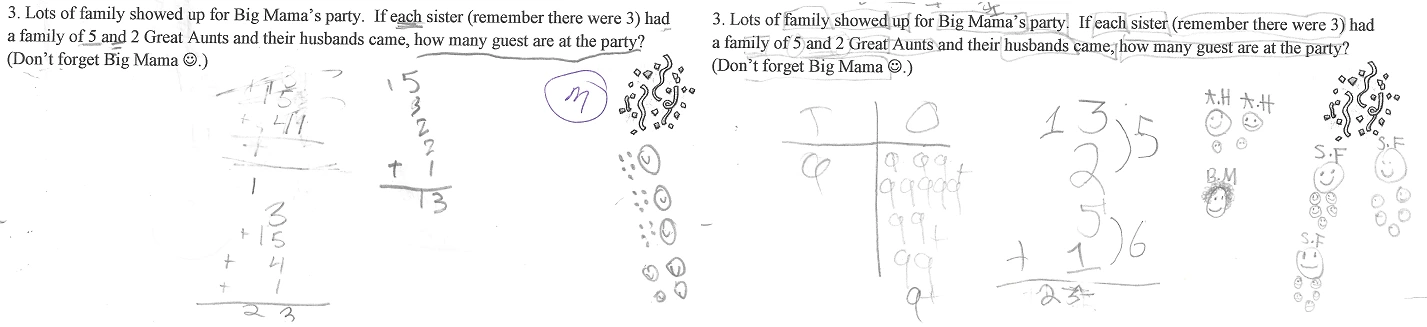

This variety of responses also occurred when determining how many people were coming to the party (see Figure 3). Students' work frequently showed erasures, and often a supplemental or second way of trying to solve the problem.

Figure 3. Problem 3 from student work: multiple step problem with operations.

Because students reworked their solution and/or tried another strategy to solve the problem, we concluded that students were persisting. In Problem 3 (see Figure 3), students already knew that everyone came to the party with their own family, and like the characters in the story, they would need to total the number of guests. Most students went straight to drawing circles as they worked through the list of families that attended. No one seemed stuck on where to start or confused about what they needed to do. Mrs. Daniels was especially delighted because in the past, students had not put much effort into the word problems from their workbook or homework.

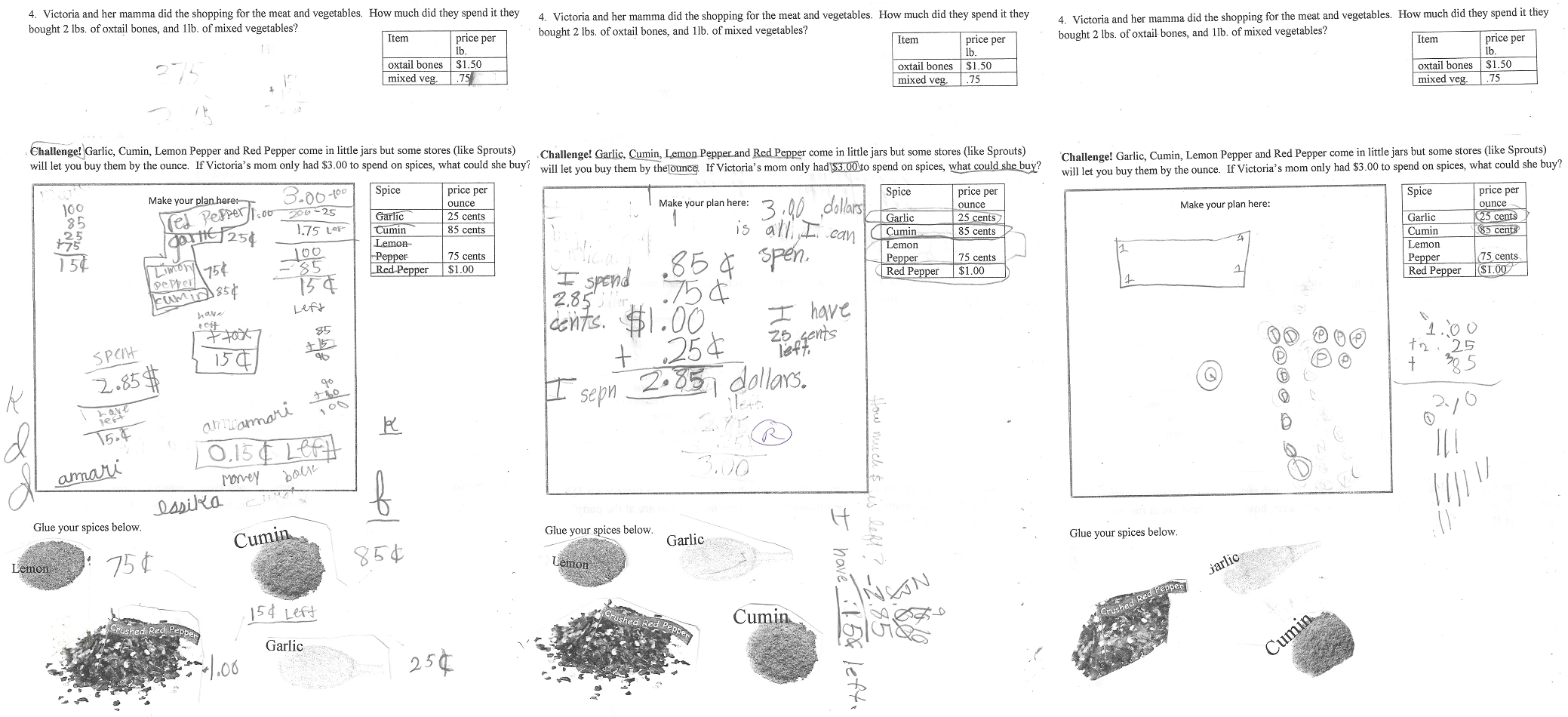

The challenge problem seemed to elicit the most reasoning. Students wrote their plan, drew out the needed coins, combined $1.00 amounts first, then the change, and glued their choices to the bottom of the page (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Challenge problem: Garlic, cumin, lemon pepper, and red pepper come in little jars, but some stores (like Sprouts) will let you buy them by the ounce. If Victoria’s mom only had $3.00 to spend on spices, what could she buy? Glue your choices at the bottom of this page.

Results

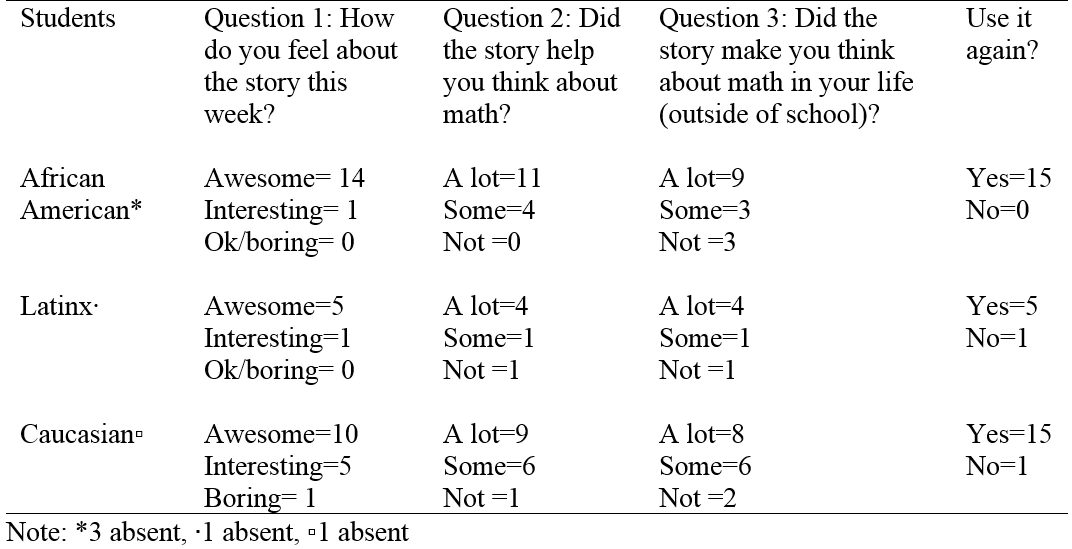

Mrs. Daniels and I recalled student behavior during the lesson and reviewed my observation protocols. We concluded that all students were engaged and we thought the story made them think about mathematics. But we wanted to find out what the students thought. Since students had reflected on their learning at the end of each lesson, we looked at this data to determine our conclusions. Figure 5 shows the reflection students completed and Table 1 shows students' responses. None of the students wrote in a response for the first three questions in this week's lesson with Just Right Stew.

When reviewing the class as a whole, it was clear from responses to question one ("How do you feel about the story this week?") that students liked the story: 96.4% thought the story was either Awesome or Interesting. The analysis revealed that all but one student rated the story positively (see Table 1). We concluded that students had connected to cooking, family dynamics and the humor in the story. We believed the results from African-American students was due in part to the affirmation of family bonds, the playful language and reactions that seemed similar to their family experiences. I was surprised by the one student who circled "boring" as a response. We thought he seemed attentive during the story and he participated in the activities and problems. When Mrs. Daniels asked him about his response, he told her that he only reads chapter books, not story books.

Questions 2 and 3 asked students how they felt the story helped them think about mathematics. The results from their reflections show that overall 94% of the students thought it helped them think about math to some degree . When asked if the story helped them think about math outside of school, 83% indicated it did to some extent . Since students in general see mathematics as school math, (Boaler, 2016), we were pleasantly surprised to see such positive responses on how the story impacted their thinking about mathematics outside of school.

Of course, one limitation of the study is that students knew their teacher would eventually see their reflections. Although they were told by the counselor while obtaining informed consent that their reflections would not impact their grades, students may have marked them more positively with hopes to please her or to encourage her to do these types of lessons more often. At the time of the study we did not have a way to verify if students connected the mathematics from the stories to their home life except for what they said in class. In retrospect, we could have asked students to create their own problems based on cooking in their own homes. This would verify that the application of mathematics transferred to their experiences. The home connections that emerged were told in stories on the playground. Mrs. Daniels recalled students conversing about family get togethers and overheard some one ask if anyone had really eaten oxtail soup before (mentioned in the story). Unfortunately, none of the students' connections seemed to include a mathematical component.

Question 4 asked students if this story should be used again for next year's class. As Table 1 portrays all but two (94%) said Yes, you should use it again. Nearly all students provided a rationale for their responses. Fifteen wrote how next year's students would enjoy the story. Nine students mentioned the stew (how to make it, tasting it, or liking it), and eight mentioned learning mathematics in general. Among those eight, two specifically wrote adding and subtracting. Two students wrote no. One wrote it was a fun book but it did not help her with mathematics, and the other (the same boy who told Mrs. A later he only read chapter books) wrote, "It was forribal." I believe he meant horrible.

We also asked, "Can you make a personal connection to this story? Why or why not?" We received a variety of answers since we purposely did not model an answer for fear of influencing their thoughts. Overall, 70% of the students, including all African-American students, said yes and wrote a connection. Most connected to a family bond and/or cooking with statements like, "One time I made soup with my grandma" and "I always make soup with my mom." Another said, "Yes, because I made cupcakes with my grandma." A Caucasian boy said, "I always color under the table like Lil (a secondary character) and I cook stew." As in all good stories, students, regardless of ethnicity, seemed to see themselves reflected in the story. We also read some unexpected comments like, "No, because I don't like red pepper in my stew" and "No, because the main characters is just a family with husbands and wives." Students' comments led us to believe that most were thinking about the actions of the story as well as connecting to the family in the story.

Conclusions

Our analysis of students' work and reflections along with our observations revealed that using high quality stories like Just Right Stew was certainly powerful in engaging students and encouraging them to spend time thinking mathematically. As seen in the students' work samples, they completed the activities with enthusiasm and effort. Students also practiced thinking and talking mathematically during practice time, and even strongly indicated through their reflections that they thought the story helped them think about mathematics. Although we could not say conclusively that students felt the story affirmed African-American culture, this story was highly rated by almost all students. The data revealed that students were engaged in the story during the read aloud, and most connected to the family bond and act of cooking. Reviewing the data also led us to believe that all students, including the African-American students, enthusiastically worked on the connected mathematical activities.

We determined that incorporating high quality culturally responsive literature into mathematics instruction was a powerful way to bring in real life mathematics to the typical tradition of isolated skills in repeated computation or word problems. Using the story also leveled the playing field for problem solving since students could use their background knowledge from hearing the story to understand the context of the problem and ultimately to understand what the problem was asking.

We learned that using these stories helped students connect to the process of doing mathematics and reinforced the cognitive development from using concrete to representational to abstract representations. In the past, Mrs. Daniels noted that students often complained of not knowing what to do. They just guessed at what to do and moved onto the next problem. Conversely, students in this lesson were eager to solve the problems based on the stories because they had seen and heard the context of the problem. For example in Problem 3, Big Mama had determined the number of guests coming to her party because the illustration shows that she had enough soup and enough places at the table for everyone. This was the concrete. Most students drew symbols to represent the people. Some students moved to abstract by using only numerals.

We also learned that students used peer-assisted learning (Van DeWalle, 2013) because some who were confused about how to use the mathematical operation compared their work to a classmate's work and many tried another way to solve the problem. Students had the same experience of hearing the story to compare and this prior knowledge seemed to lead students to talk about it more and assist each other in solving the problems. Since the story lead students to learn from each other and to develop concepts through cognitive development (concrete to representational to abstract thinking), we strongly recommend using stories as a platform for problem solving.

We believe using these stories was instrumental to helping students see mathematic word problems as stories with real mathematical action, instead of calculations in isolation. Prior to our study, students struggled to understand the mathematical action of word problems because they did not know the story behind the problem. Since students knew the context of the mathematical action in the story with Big Mama, they were able to connect to the mathematical action in the word problems from the story. We are hopeful that this experience with problems from the story will help students to visualize or draw the action in other problems they encountered in other contexts (e.g. standardized tests).

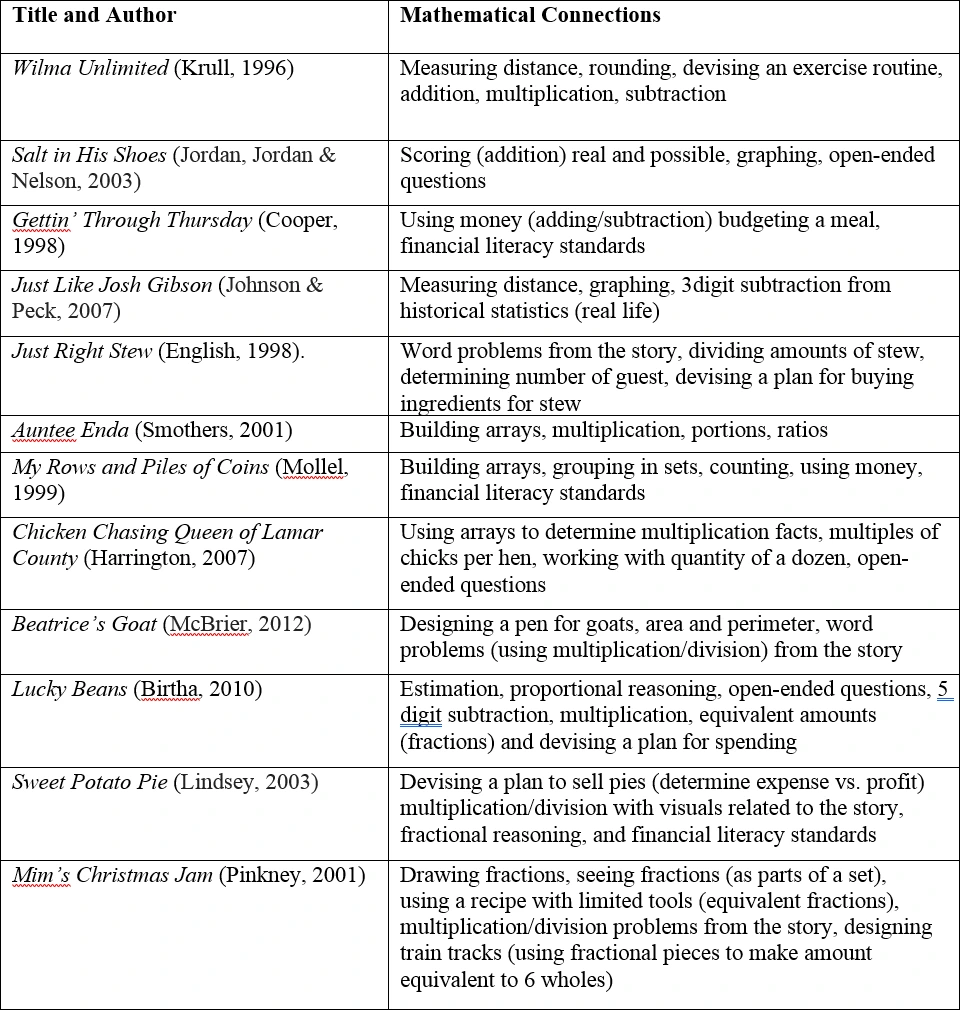

Mrs. Daniels and I also recommend using multicultural stories in mathematics instruction because it was enjoyable. We revelled at how engaged students were in each lesson and by how well they were getting along with each other. We believe this strategy is a strong attempt at culturally responsive teaching by affirming a marginalized culture and providing time for students to learn about the positively portrayed traits as illustrated in the story. Since students connected with each other about themes from the story (e.g. food, words, family relationships of joy and struggle), students realized that they had more in common with each other than they had previously thought. This promotion of inclusion and community is what we hope to see in all classrooms, including mathematics. Figure 6 lists the story titles and math connections we used in this study.

Figure 6. Stories used in this study (Corp, 2017).

My next steps are to continue the effort to encourage culturally responsive teaching in mathematics. I am creating a longer list of stories that lend themselves to connections to mathematics while promoting cultures, particularly Latinx and African-American cultures. I also plan to research students' responses to stories that promote Latinx characters (particularly Mexican-American characters) in Southwestern public schools. My hope is that our stories inspires teachers to use a story that reflects various cultures as a way to connect to mathematics, and to promote inclusion and affirmation of all students.

References

Altieri, J. L. (1993). African-American stories and literary responses: Does a child's ethnicity affect the focus of a response? Reading Horizons, 33(3), 5.

Copenhaver, J. F. (2001). Listening to their voices connect literary and cultural understandings: Responses to small group read-alouds of "Malcolm X: A fire burning brightly." New Advocate, 14(4), 343-359.

Corp, A. (2017). A story of engaging all students: Using research to guide teaching practices. Early Years, 38(1), 16-19.

English, K. (1998). Just right stew. Honesdale, PA: Boyds Mills Press.

Ensign, J. (2003). Including culturally relevant math in an urban school. Educational Studies, 34(4), 414-423.

Gay, G. (2002). Preparing for culturally responsive teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(2), 106-116.

Hefflin, B. R., & Barksdale-Ladd, M. A. (2001). African American children's literature that helps students find themselves: Selection guidelines for grades K-3. The Reading Teacher, 54(8), 810-819.

Tatum, A. W. (2006). Engaging African American males in reading. Educational Leadership, 63(5), 44.

Wilburne, J. M., Keat, J. B., & Napoli, M. P. (2011). Cowboys count, monkeys measure, and princesses problem solve: Building early math skills through storybooks. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing Company.

Whitin, P., & Whitin, D. (2004). New visions for linking literature and mathematics. Urbana, IL: The National Council of Teachers of English.

Dr. Amy Corp is Assistant Professor in the department of Curriculum and Instruction at Texas A&M University-Commerce.

WOW Stories, Volume V, Issue 4 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/wow-stories-volume-v-issue-4/2.