Creating More Windows to the World: Exploring Amish-Themed Children's Literature

By Kristen Noll and Darryn Diuguid

Because the U.S. population is greatly diverse, educators are tasked to teach their students about the many cultures in the United States. One of the most important skills teachers strive to develop in their practice is an ability to build on the knowledge students bring into classrooms, particularly knowledge shaped by their families, community, and cultural histories (Hughes, 2012). Many classrooms are comprised of students of differing ethnicities and religions, and as such, it is important for teachers to understand their students' cultures so they can embrace their cultural assets. Additionally, understanding a student's culture enables a teacher to communicate more effectively with that student's family. On the flip side, students, too, benefit from learning about what people in cultures that differ from their own value and believe. One group, the Amish, is a distinct ethnic and religious group that has lived in the United States since the 1700s and has an extraordinary culture and history few mainstream Americans know much about. Studying the Amish along with other cultures represented in schools enables students to explore and compare their own culture and values with those reflecting a range of ways of being in the world.

Incorporating the Amish Culture in Your Classroom

There are many ways educators can incorporate Amish-themed children's books to support students in making connections to broader understandings of cultural diversity, while simultaneously addressing the Common Core State Standards. For instance, one of the key features of the Common Core State Standards is a push to include more informational texts in the classroom; in fact, the Common Core states that "students need sustained exposure to expository text to develop important reading strategies, and that expository text makes up the vast majority of required reading in college and the workplace" (NGA & CCSSO, 2010, p. 3). Zapata and Maloch (2014) also state that when students are given opportunities to use informational texts, they "grow in their comprehension of such texts and in their use of these genres, strategies, and structures of their own writing" (p. 27). Language arts teachers use these books as mentor texts in writing workshops, as read alouds, and as texts in reading workshop or literature units. These books can also be used across the curriculum as thematic units, to build community, or to teach about diversity throughout the United States.

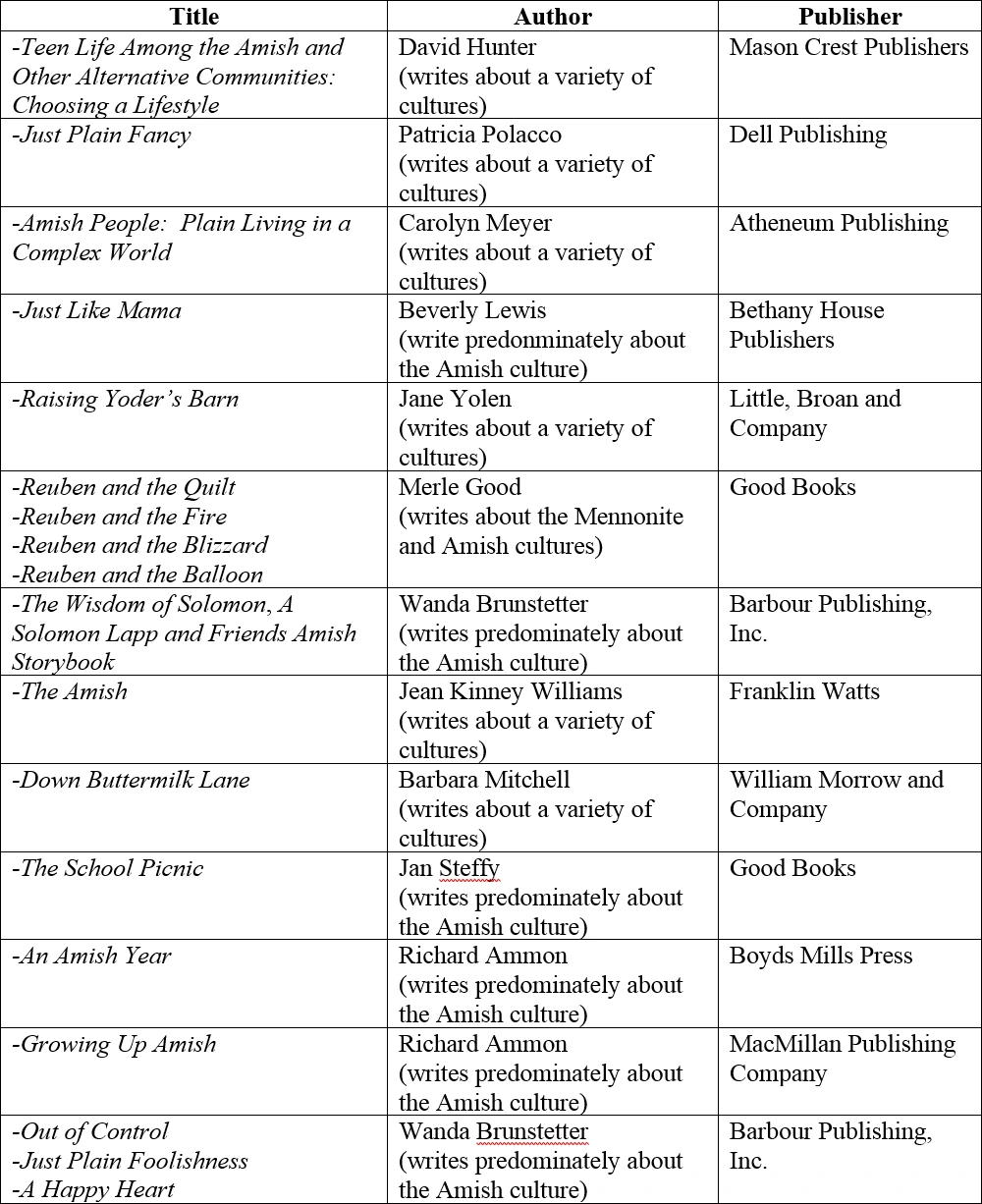

We decided to review Amish-themed children's literature to better expand our knowledge of the culture and to see if, and what kind, of trade books were available. Our initial questions included: what are the values and beliefs of the Amish, in what ways do Amish value education and educate their children, and how do Amish children's lives differ from mainstream society? When first starting this project, we searched via the school's library using key words such as "Amish" and "children's literature." From there, we decided to review the books listed below to see if there were themes which existed across the fifteen books that came up in our initial search. After reading the texts, we grouped the books according to themes and found overarching categories. Upon further research about the authors and publishers, we realized some of the publishers and authors were from the Amish culture or Mennonite culture, while others were considered cultural outsiders; that is, authors who research and write about a variety of cultures they are interested in but not necessarily a member of. The publishing dates of the children's books ranged from 1976-2009, and so we wondered if the traditions presented still exist today.

Values and Beliefs of the Amish

Like all cultural groups, the Amish have values and beliefs that are of great importance to them. Teen Life Among the Amish and Other Alternative Communities: Choosing a Lifestyle, a nonfiction children's book written by David Hunter (2008), explains that Amish life is dictated by a list of unwritten or oral rules, known as the Ordnung. The Ordnung directs everything in Amish life, including religious rituals, family life, clothing, use of technology, and farming techniques (Hunter, 2008). "More so than in most other communities, the Amish Ordnung is extremely important for the identity, growth, and vitality of the Amish community" (Hunter, 2008, p. 38). We learned that each Amish community decides on its own rules so Ordnungs vary. If members of the Amish community do not follow the rules, they may be shunned.

A fiction picturebook authored by Patricia Polacco (1990), Just Plain Fancy, suggests that Amish children are concerned about following the rules. Because the Amish embrace simple living, plain dress and a hesitancy to embrace modern technology for its convenience are important. Two sisters named Naomi and Ruth are afraid that their peacock they named Fancy is too fancy because of his vibrant colored feathers. One afternoon Naomi and Ruth overhear their family talking about a woman in a neighboring Amish community being shunned because she dresses too fancy, and so start worrying that Fancy could be shunned in their community. At the end of the story, Naomi and Ruth are relieved when they learn that Fancy will not be shunned because he was blessed naturally by God with his beauty.

Family is another value that is important in the Amish culture. Amish have large families because they rely on one another for the success of their rural lifestyles. Children are instrumental in helping with chores such as maintaining the farm and house. Carolyn Meyer (1976) explains in her award winning book Amish People: Plain Living in a Complex World, "From the time of birth, Amish children are prepared for their roles in the family and in the Amish community: girls are welcomed as 'little housekeepers' and 'dishwashers,' boys are 'little woodchoppers' and 'farmers'" (Meyer, 1976, p. 119). Amish children learn their roles from their parents.

Just Like Mama, a fiction picturebook authored by Beverly Lewis (2002), tells the story of a little girl, Susie Mae, who wants to be just like her mother. The illustrations depict Susie Mae following her mother around and doing chores such as collecting eggs, picking berries, cooking meals, and milking cows. Her brother, Thomas, explains, "you can cook and clean, milk and pick berries, but...Aw, Susie Mae, there's a whole lot more to Mama than what she looks like and what she does" (Lewis, 2002, p. 27). Susie Mae realizes that she wants to be patient and kind just like her mother.

Our analysis identified another theme in the literature and stories in the Amish helping each other in hardships and caring for each another. Jane Yolen's (1998) Raising Yoder's Barn, another fiction picturebook for young readers, tells the story of the Amish coming together to help rebuild a neighbor's barn after it burned when struck by lightening. The Amish consider it an honor to participate in a barn raising. An Amish boy explains in the story, "And sixty feet by forty feet, to the sound of many hammers ringing, that barn grew like a giant flower in the field all in a single day" (Yolen, 1998). As described in Merle Good's (1993) Reuben and the Fire, a "barnraising is like a holiday" (p. 25). While the men work on the barn, the women cook all day to feed the men; everyone in the community helps (Yolen, 1998; Good, 1993).

Another aspect of the value the Amish put on helping each other can be understood in how the Amish handle conflict. In Amish People: Plain Living in a Complex World (Meyer,1976), the author reveals that the Amish are pacifists, and, therefore, avoid violence and practice forgiveness. Reuben and the Quilt (Good, 1999) provides a powerful example of the intersection between pacifism, forgiveness and helping those in need. This story is about a family making a quilt to donate to an auction for a neighbor who is injured when a car crashes into his buggy. The community comes together and has an auction to help pay for medical expenses. The quilt the family makes in the story is stolen off of their porch. The children have a difficult time understanding how someone could steal the quilt until their father explains that "maybe the thief is really poor and needed it." The father suggests that they leave the matching pillowcases outside for the thief to take, because he needs something to lay his head on while he is sleeping with the quilt. They do just that, and to their surprise, the next morning they find the quilt returned.

Another fiction picturebook featuring Reuben titled Reuben and the Blizzard (Good, 1995), tells a story about the Amish helping a non-Amish family. In this story a husband explains to his Amish neighbors that his wife is having a baby and he cannot get his car through the snow to take her to the hospital. The Amish family use their horse and sleigh to take the couple to the mainroad to meet an ambulance. Another story supporting Amish helping non-Amish is found in Wanda Brunstetter's (2009) The Wisdom of Solomon, A Solomon Lapp and Friends Amish Storybook, a compilation of short stories about a little boy named Solomon. In "A Friend in Need," Solomon learns during a sermon one Sunday morning that if he is generous, he will be blessed. He then tries to figure out what being generous means. After a few misconceptions about the idea of being generous, he realizes what it means when his English neighbor, David, declares one morning at the bus stop that he is not doing so well lately because his father lost his job and so he does not have food for lunch, and so Solomon gives David his lunch. Later that evening, Solomon shares David's news with his family. Solomon's mother explains they need to help David's family. They take David's family a basket of food, and Solomon's father speaks with other members of their community to help with more food and money. From reading these children’s books, the message is conveyed that even if the Amish live in a way that differs from mainstream society, they do not hesitate to help in a time of need.

Amish’s View on Education

The Amish view education differently than mainstream society; that is, they go to school to learn what is needed to be a practicing farmer, laborer, carpenter, or carriage maker. Albeit they begin schooling their children at the age of five as most parents do in the U.S., they cease formal schooling after the eighth grade so their children can help at home and on the farm. By doing so, they learn the work traits that are expected as adults. Hunter (2008) explains, "One of the more frequently quoted verses of the Bible among the Amish when they are speaking of education comes from 1 Corinthians 8:1 'Knowledge puffs up but ... anyone who claims to know something does not yet have the necessary knowledge" (p. 63).

Meyer (1976) explains how Amish children who attend school wake up early to work on their chores before school and continue chores when they return home. Richard Ammon's (2000) fictional picturebook for younger children, An Amish Year, describes a year in the life of Lizzie, an Amish school girl. Lizzie explains that students (or scholars as they are referred to in the book) are never assigned homework because the need for them to complete chores at home is more important.

An illustration in An Amish Year depicts a classroom with a chalkboard, old chairs, and a wood burning stove. The simplicity of the classroom reflects their chosen lifestyle. On the opposite page, Lizzie explains, "Our day begins when Sara rings the bell...After taking attendance, she reads verses from the Bible, but we do not say the Pledge of Allegiance. There is no flag in our school" (Ammon, 2000, unpaged). In the Amish culture, saying the Pledge of Allegiance is thought of as placing an allegiance to country above everything, even God, and that is why the pledge is not practiced in schools. Growing Up Amish, a biography written about an Amish girl also written by Richard Ammon (1989), reveals that the Amish do not believe in submitting to any government, federal or local, because of their mistreatment long ago by European governments. Interestingly, although most Amish children do not attend public schools, their parents are still required to pay school taxes in most communities (Hunter, 2008).

The Amish, a nonfiction children's book by Jean Williams (1996) explains that Amish children learn mathematics, English, and some history, geography, and health. They do not teach religion because it is the responsibility of parents to do so (Williams, 1996). Their textbooks even support their lifestyle. "The Old Order Amish have developed their own texts in which readers will find no sex education, fairy tales, or stories with talking animals or mention of magic" (Williams, 1996, p. 79).

Amish school teachers do not attend college or even graduate from high school. Their education ceased after eighth grade just like their students' education will. Those who are good students in school are asked to be school teachers (Ammon, 1989). Williams (1996) explains that teachers serve as apprentices before they have their own classrooms, and younger teachers learn from teachers who have more experience. Amish teachers from other districts meet during the school year to discuss schooling. In addition, Amish teachers refer to a magazine published by a company in Ontario, Brushing Up on Pronunciation, to share ideas and techniques (Williams, 1996). A few Amish children attend rural public schools, but most attend one-room schools constructed by the Amish. Mirroring early education in America, the teacher is responsible for keeping a controlled environment with a wide range of ages and grade levels (Hunter, 2008). School teachers are always single; when they marry their responsibility shifts to the home.

Competition is discouraged among students because the Amish believe in unity. Hunter (2008) explains that, "Independent thought and critical analysis--the sort of questioning that many mainstream teachers try to encourage in their students--are frowned on" (p. 62). Students who are more intelligent than others do not receive enriched instruction as students would in mainstream society. The sole purpose of schooling in the Amish community is to teach students what they need to know to participate in the community. However, they learn the most important skills for participation in the Amish culture from their parents and other adults in the community (Meyer, 1976). "Nevertheless, tests taken by Amish and non-Amish students alike show that the Amish students do just about as well as their mainstream counterparts in those subjects they have in common" (Hunter, 2008, p. 62-63). The Amish believe that hard work, humility, and honesty make a better person, not education.

The Amish did not always have the right to educate their children in their own parochial schools. Until courts became involved, the Amish had to send their children to public schools. Laws governing education became more prominent in the 1920s and 1930s. Rural schools were consolidated into one central location, and the Amish were against this; they wanted their children to attend school close to home. Moreover, the Amish did not want to send their children to high school (Williams, 1996). Their practice of a shortened formal education caused controversy among the Amish and various state governments. "In 1921, Ohio legislators passed a compulsory education law requiring schooling through age eighteen" (Williams, 1996, p. 70). "There were many unpleasant incidents when truancy laws were enforced by school districts unwilling to lose state subsidies based on attendance; Amish fathers were often arrested and jailed for refusing to send their older children to school" (Meyer, 1976, p. 46). Most of the Amish families eventually complied with the Ohio law and applied for work permits for children when they turned sixteen (Williams, 1996). In the 1930s, the Pennsylvania legislature made it mandatory to stay in school until age fifteen, thus requiring a year of high school. For two years, Amish men lobbied for religious freedom to have their children educated as they choose so that by 1937, "many Amish fourteen-year-olds were literally hiding at home, and one father was jailed" (Williams, 1996, p. 71). The Amish eventually won the right to apply for work permits for their children, however, by 1949 Pennsylvania raised the compulsory education age to sixteen, resulting in more arrests of Amish parents (Williams, 1996). In 1955, the State of Pennsylvania and the Amish compromised so that compulsory attendance laws would not be broken and Amish religious beliefs would not be violated. Amish children were compelled to attend vocational school after their completion of eighth grade on Saturday for three hours to study hygiene and more advanced subjects such as arithmetic and English than they would in regular school. They were also required to keep journals of the work done in their homes and on their farms each week (Meyer, 1976). The State of Iowa also had a conflict with the Amish in 1965. In lieu of sending their children to a public school, an Amish community in Buchanan County established their own elementary schools with Amish teachers (Williams, 1996). An authentic photograph taken by the media in The Amish depicts a police officer watching Amish children running away for safety in response to a command by an Amish adult, when a school bus arrived to transport them to the public school. This photograph was nationally published, and the Amish received support from many non-Amish nationwide. However, conflicts continued.

Eventually, the nation's highest court became involved. The Supreme Court ruled in Wisconsin vs. Yoder (1972) that Amish children could not be forced to attend school past eighth grade. In other words, the State of Wisconsin's interest to educate its children was not more important than the rights of the Amish to practice their way of life. Amish children were no longer required to attend school on Saturday and keep journals of their farm work in Pennsylvania or any other state. To this day, Amish have a shortened educational career. In fact, Fischel (2012) states:

Their children did not have to complete more than eight years of formal education, and the Amish could establish their own parochial schools with Amish-approved teachers. In Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana, where the majority of the Amish reside, a program of home-based vocational education was required for another two years, but most of this involved homebased training that Amish teenagers would have received without state compulsion. (p. 114)

The Lives of Amish Children

The literature we examined also revealed that an Amish child's life differs from that of a child in mainstream society, but not as drastically as one may think. While there are obvious differences, Amish children have many similarities to children of mainstream society, especially those who live in rural areas.

Reuben and the Balloon, a fiction picturebook authored by Good (2008), suggests that Amish children are just as curious as other children. This book presents another story about Reuben, who is enamored with hot air balloons that he sometimes sees flying over his family's farm. One afternoon he suggests to his grandfather that they should race one of them in their buggy. They are unsuccessful in beating it and go back to their farm. Another afternoon he watches a balloon descend from the sky. Reuben decides his chores can wait and goes to see where it landed on a nearby farm. The pilots asked for something to drink, and the Amish give them water. The pilots then take Reuben and two other Amish boys for a ride, and the illustrations depict Reuben smiling during the ride and happily waving to the horses and chickens below him.

Barbara Mitchell's Down Buttermilk Lane (1993) is a fiction picturebook that tells the story of Amish children shopping with their parents just like children in mainstream society. This book tells the story of an Amish family who take a trip one fall morning into town to shop; instead of parking a car, they park their buggy. They purchase food and clothing from different stores in town. After they finish shopping, they visit Dawdi (Grandpa) and Mammi (Grandma) for a home-cooked meal. After they are finish eating, the Amish children take a walk to the pond with their Dat (Dad) and Dawdi.

Just as children in mainstream society, Amish children look forward to the last day of school before summer vacation begins. In Jan Steffy's The School Picnic (1987), a children's fiction picturebook, the reader can feel the excitement as the Amish children wait for lunchtime when they get to enjoy a picnic with their families and teacher. After they eat, children read poems and present a program. The children enjoy the rest of the day playing games, such as softball with their parents and competing in egg relay races.

In An Amish Year (Amman, 2000), Lizzie cannot wait to fly a kite on a spring day, but she must finish her chores first. This book references activities that Amish children enjoy during the seasons just as children in mainstream society, such as: fishing, playing softball and volleyball, running around barefooted, sledding, ice skating, and playing board games like Monopoly.

Amish children also fabricate stories and cover up mishaps just like mainstream children. The wisdom of the fictional character, Solomon, supports this notion in the short story, "Stretching the Truth" (Brunstetter, 2009). Solomon's sister, Sarah, struggles to admit guilt when she does something wrong, and does not always tell the complete truth. For example, when she and Solomon wash dishes one afternoon, Sarah drops and breaks their mother's favorite dish. Instead of telling their mother, she buries the dish in the trash can. Solomon explains to his sister that stretching the truth is almost the same as telling a lie. Later that day, Sarah lets her friend play with Solomon's yo-yo, which she breaks. Instead of telling Solomon the truth, Sarah throws the yo-yo into the haystack in the barn to hide it. When Solomon finds it and questions her, she proclaims she does not know who broke it. In the end of the story, Sarah realizes that telling the truth is always the right thing to do.

To further support the idea that Amish children get into trouble and make mistakes, a reader can enjoy a series of books written by Wanda Brunstetter about Rachel Yoder, an Amish girl who always finds trouble. For example, in Out of Control (2008), Rachel is determined to beat her friend in a sled race during recess so she waxes the runners. Her rope breaks during the race, and because she is going so fast due to the waxed runners, she crashes into a creek. She returns to class in soaked clothes, and her teacher scolds her for waxing her sled runners, explaining that she does not always have to win. Rachel is sent home for the day so she will not catch a cold. Rachel's day does not improve. After she takes a warm bath, she helps her mother make a shoofly pie, and Rachel gets to make another pie with the leftover dough. She learns that evening during dinner that she must not have measured the ingredients properly because her brother exclaims, "This is the worst shoofly pie I've ever tasted! It's not even fit for a fly!" (Brunstetter, 2008, p. 31). Rachel bursts into tears and leaves the room.

Rachel finds trouble again in Just Plain Foolishness (Brunstetter, 2008). In this story, Rachel experiences jealousy over the birth of her new baby sister, Hannah, born on her birthday. All Rachel wants for a gift is to visit Hershey Park, an amusement park. Rachel's family is too consumed with the baby to take Rachel to Hershey Park, so she decides to visit with two of her English friends, without permission from her parents. What starts out as an exciting trip turns out to be frightening. Rachel decides to wander around the park while waiting on her friends to finish riding a roller coaster and gets lost. She starts to miss her family and worry if she will even see them again. She eventually finds her friends. Wiping away tears from her face, Rachel says, "I'll never go anywhere again without my parents' permission" (p. 153). When Rachel gets home and explains the situation to her parents, Rachel's English friends explain that they also need to get home because they do not want their parents to worry either.

Stories about the Amish show that children tease each other just like children in mainstream society, especially brothers and sisters. In A Happy Heart (Brunstetter, 2008), Rachel gets eyes glasses. She does not want to get them until she tries them on and realizes she can see much better. She is feeling better about wearing them until her brother tells her, "I didn't realize your glasses would be so thick. Ha! Now you have four eyes instead of two" (p. 95). Rachel is apprehensive about wearing her glasses to school the next day. Their mother warns her brother, Jacob, not to tease her sister anymore. Rachel asks her mother what she should do if anyone else teases her. Her other brother, Henry, answers that she should tell the teacher. Rachel explains she will be called a tattletale and Jacob tells her she already is a tattletale. The bickering continues between Rachel and her brother. Just as Rachel predicted, she is teased at school about wearing glasses. The teacher intervenes and announces to the class, "Poking fun at someone and making rude remarks is wrong. I won't tolerate anyone in this class making fun of another person for any reason at all" (p. 136). Rachel's experiences with her brother and classmates reflect issues with which almost all children can identify.

The life of an Amish child does have differences from many children in mainstream society. For example, Amish children may have more chores to do, and are often educated differently. Hunter (2008) explains, "Amish teens are usually thirteen years old when they finish their schooling. At that point, many of them go to work, usually either at home or for a relative" (p.63). However, they are still not considered adults, and must obey their parents. They do gain more freedom when they turn sixteen because this is the age Amish children can decide whether or not they would like to be baptized, which officially makes them a member of the Amish church. This time of independence in an Amish child's life is referred to by the Amish as Rumspringa (Hunter, 2008). This period allows the Amish child to "experience the life of a non-Amish person" and "to do things normally forbidden amoung the Amish" (p. 65). During this time, Amish children may wear different clothing, listen to music, play video games, and other things mainstream teenagers enjoy. "In some cases, young people might even experiment with alcohol and drugs...those extremes are rare, however. Most Amish teenagers never stray far from their upbringing" (pp. 65-66). Their strong family and community values most often prevail in their decision to remain Amish.

Final Thoughts

In most Amish schools, children transport themselves to school in a horse and buggy, and they responsibly secure their horses to the hitching rail. They enter the schoolhouse and greet the teachers, not moving until they received a reply. They then venture out into the schoolyard to play until class commences. Instead of reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, they begin their day by singing hymns, reading passages from the Bible, and reciting the Lord's Prayer. The teacher takes attendance by asking each student what chores he or she did before coming to school that day. Grades one through four are in one room, and grades five through eight are in the other. Both rooms have wood burning stoves and old chalkboards. The schoolhouse has a bell that one of the teachers rings by pulling on the rope when it is time for school to begin. The teachers work with each grade at a time using various supporting materials, such as workbooks and flashcards. The children sit quietly and respectfully, and they do not speak unless directed to do so.

Non-Amish will continue to be intrigued with the Amish, and books about them will continue to be written for children and adults to enjoy. K-12 students who may find this culture interesting due to the dress, traditions, and daily activities will learn, as we did, through reading this set of texts, the values and dreams that they share with Amish people as well as what makes their culture unique. The Amish are simple, hardworking, and caring people and the children's books we read about this culture supported these perceptions. Additionally, we learned they value educating their children, but in a different manner than children are educated in mainstream society. These books portray Amish children enjoying many of the same activities that other children do and so students will be able to understand similarities and embrace differences. Such knowledge, we argue, enriches us all.

References

Banks, J., Cookson, P., Gay, G., Hawley, W., Irvine, J., Nieto, S., & Stephan, W. (2001). Diversity within unity: Essential principles for teaching and learning in a multicultural society. Seattle, WA: Center for Multicultural Education, University of Washington.

Fischel, W. A. (2012). Understanding education in the United States: Do Amish one-room schools make the grade? The dubious data of Wisconsin vs. Yoder. University of Chicago Law Review. Vol: 79, 107-129.

Hughes, S. (2012). How can we prepare teachers to work with culturally diverse students and their families? What skills should educators develop to do this successfully? Boston, MA: Harvard Family Research Project.

Hunter, D. (2008) Teen life among the Amish and other alternative communities: Choosing a lifestyle. Philadelphia: Mason Crest Publishers.

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, & Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010). Common Core State Standards, Appendix A. Retrieved from http://www.corestandards.org/assets/Appendix_A.pdf.

Tharp, B. M. (2007). Valued Amish possessions: Expanding material culture and consumption. The Journal of American Culture, 30(1), 38-53.

Zapata, A, & Maloch, B. (2014). Calling Ms. Frizzle: Sharing informational texts in the elementary classroom. Journal of Children's Literature, 40(2), 26-35.

Children’s Literature Cited

Ammon, R. (1989). Growing up Amish. New York: Macmillan.

Ammon, R. (2000). An Amish year. Honesdale, PA: Boyds Mills.

Brunstetter, W.E. (2008). A happy heart. Uhrichsville, OH: Barbour.

Brunstetter, W.E. (2008). Just plain foolishness. Uhrichsville, OH: Barbour.

Brunstetter, W. E. (2008). Out of control. Uhrichsville, OH: Barbour.

Brunstetter, W. (2009). A friend in need. In The Wisdom of Solomon, A Solomon Lapp and Friends Amish Storybook (p. 88-108). Uhrichsville, OH: Barbour.

Brunstetter, W. (2009). Stretching the truth. In The Wisdom of Solomon, A Solomon Lapp and Friends Amish Storybook (p. 214-234). Uhrichsville, OH: Barbour.

Good, M. (1993). Reuben and the fire. Intercourse, PA: Good Books.

Good, M. (1995). Reuben and the blizzard. Intercourse, PA: Good Books.

Good, M. (1999). Reuben and the quilt. Intercourse, PA: Good Books.

Good, M. (2008). Reuben and the balloon. Intercourse, PA: Good Books.

Lewis, B. (2002). Just like mama. Minneapolis, MN: Bethany House.

Meyer, C. (1976). Amish people: Plain living in a complex world. New York: Atheneum.

Mitchell, B. (1993). Down Buttermilk Lane. New York: William Morrow.

Polacco, P. (1990). Just plain fancy. New York: Dell.

Steffy, J. (1987). The school picnic. Intercourse, PA: Good Books.

Williams, J. K. (1996). The Amish. Danbury, CT: Franklin Watts.

Yolen, J. (1998). Raising Yoder's barn. Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

Kristen Noll teaches fifth grade at Columbus Elementary School in Edwardsville, IL.

Darryn Diuguid is an Associate Professor of Education at McKendree University in Lebanon, Illinois where he is the edTPA Coordinator and teaches Children’s Literature, Adolescent Literature, Learning and Teaching Language Arts, and Learning Environment.

WOW Stories, Volume V, Issue 4 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/wow-stories-volume-v-issue-4/2.