Learning and Making Global Connections Through Town Is by the Sea

By Robbie Stout

Global children's literature is important to my teaching. I read it to enhance my curriculum because it adds complex text, rich illustrations, and global characters and settings. Through stories in global literature students learn about themselves and others around the world and begin to understand that “their perspective is one of many ways to view the world” (Short, 2009, p. 4).

I have been teaching kindergarten students for 10 years. My current school is quite diverse. In 2018, my kindergarten class of 21 students (13 girls, 8 boys) was 38% African American, 4% Asian, 2% Russian, 2% Hispanic, and 54% European American. One student was an English Language Learner. The global literature we read and discussed provided mirrors for students to see themselves and their classmates in books as well as windows to learn about others in the world (Bishop, 1990).

Storying Studio

Even though I read aloud to students throughout the day, Storying Studio is a special time set aside to read and discuss stories. Students love Storying Studio. Our daily Storying Studio lesson always includes reading a mentor text, discussing the story, and engaging in a mini-lesson on an aspect of writing or art. Following the lesson, students have time to explore, write, and illustrate related to the mini-lesson focus. At the end of Storying Studio, students take a seat in the Author’s Chair (Fletcher & Portalupi, 2001) to share their stories with their peers. Peers respond with compliments and feedback. Each student has a Storying Studio folder to keep ideas for characters, stories, and their works in progress.

Depending on my purpose, I use both global literature and other literature as mentor texts in Storying Studio to highlight specific aspects of art. With kindergarteners, to focus on art I find it helpful to use literature with large clear illustrations. For example, I like to use Elephant and Piggie books by Mo Willems and The Rain Came Down by David Shannon (2000) to talk about how artists use lines to indicate movement and expression. When Sophie Gets Angry, Really, Really Angry by Molly Bang (1999) works well for talking about color and emotion. Louise Loves Art by Kelly Light (2014) and The Sandwich Swap by Queen Rania of Jordan Al Abdullah, Kelly DiPucchio, and Tricia Tusa (2010) are helpful for discussing contrast; how, for example, artists use different types of lines, colors, or textures for different purposes. The use of mentor texts inspires students’ creativity and imagination.

Mini-Lessons on Placement

This year students were excited to explore how images are placed and positioned on the page. We started the inquiry with an exploration of book gutters. Gutters are where the pages come together in the book’s spine. I introduced gutters using Shy by Deborah Freedman (2016) and This Book Just Ate My Dog by Richard Byrne (2014). In both of these books characters in the story are hidden or disappear into the gutter. Books like these challenge and inspire students to think about where and how they place characters in the art for their stories.

From gutters we moved to talking about horizon lines (“grass lines” as I explained to students) that separate the sky and the earth on the page. I used Over and Under the Snow (2014) and Up in the Garden and Down in the Dirt (2017) by Kate Messner and Christopher Silas Neal as mentor texts to talk about why different images in the art were placed above or below the horizon line. Students caught on quickly and created their own pencil drawings of what they thought would be over and under the snow.

To build on these understandings and broaden students’ perspectives of communities and people around the world, I read Town Is by the Sea by Joanne Schwartz and Sydney Smith (2017) as a mentor text. Set in a Canadian mining town near the sea, the story is about a boy who watches his dad go off to work in the tunnels, mining in the earth under the sea. The illustrations show contrast between the light on the ocean and the darkness of the mining tunnels.

As we always do when we read global literature, we went to the map to find the setting of the story and then added new vocabulary words, such as Canada, mining, and coal, to our anchor charts as we read. We use anchor charts to make notes about things we want to remember as we read. Students noticed many similarities between themselves and the boy in the story as they considered where their families live, jobs their parents have, clothes they wear, etc., compared to those of the boy. Because we had previously discussed placement and horizon lines students were excited about the story and immediately connected it to the previous over/under stories.

When I asked students to paint their own over/under illustrations with watercolors, they were thrilled. For this painting, I let them choose what they wanted to paint to challenge their thinking and creativity and not limit the possibilities. Before painting, I suggested they look through their Storying Studio folders for inspiration. Their folders contained lists of character ideas, their illustrations of other settings, and responses to other stories we had read together.

While students easily represented what was above and below the horizon line, many still painted a sky above. Horizon lines were a new and difficult concept for them to fully comprehend, and I knew it would take time for them to fully implement into their art.

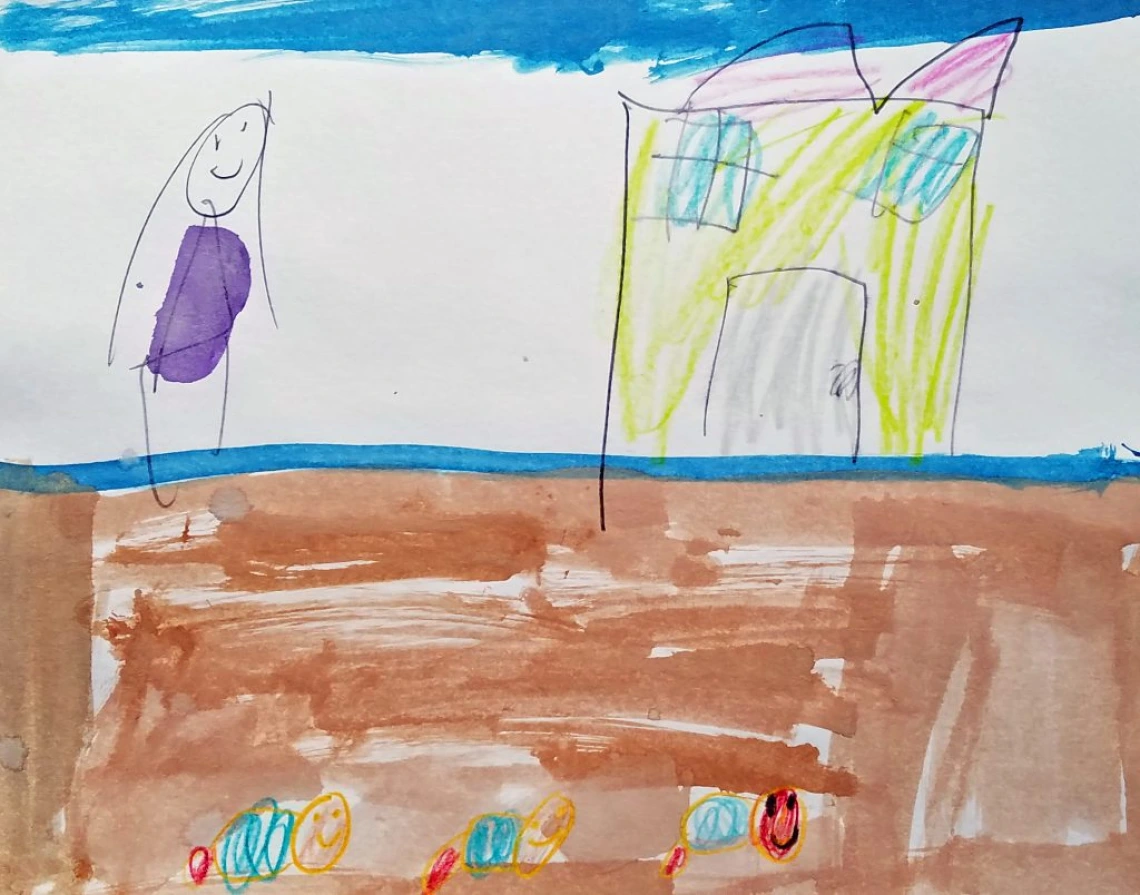

Amy chose to paint bugs crawling underground with herself standing by her house above them (see Figure 1). She stated, “I had to draw the bugs first with crayon. Then, I could paint the brown color all around them. This is me looking down on them. They live under the house.”

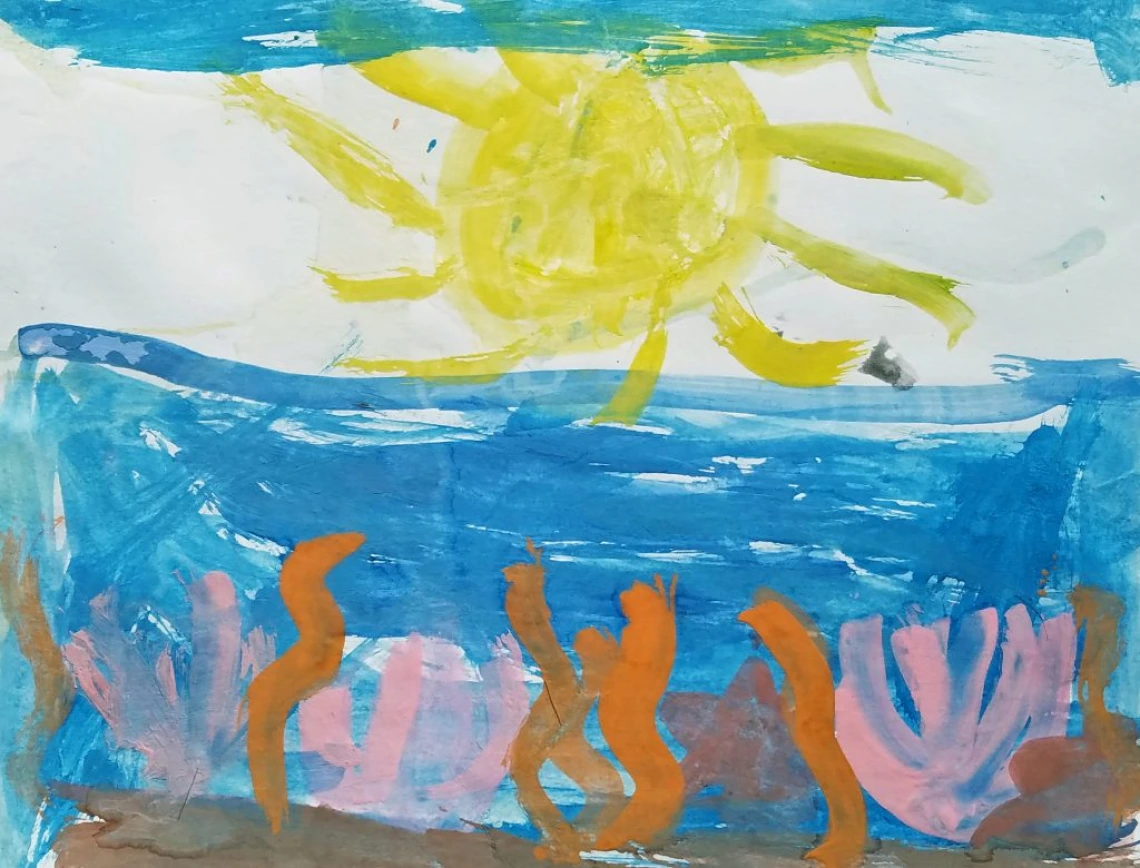

Bailey decided to paint the sea (see Figure 2). She explained, “I painted the sun shining on the water. I also painted the plants under the sea. I had to let the blue dry first so the plants would be bright and not blue.” When I asked her about the water, she clarified, “I didn’t paint everywhere blue because then you couldn’t see the light.”

Callie also painted the sea but left the underwater white (see Figure 3). She shared that she was “afraid to paint water because she wouldn’t be able to see the fish.” When I asked her about the flag, she said it was for our country, indicating she understood that we live in a different country than Canada, the setting for Town Is by the Sea.

Closing Thoughts

Students are inspired by and love listening to good, global literature stories. Through global literature they experience different ways of living and being in the world and, because it is a story, they make connections and learn (Martens et al., 2016). They enjoy seeing themselves and their lives (and those of their classmates) reflected in the “mirror” aspects of stories as well as looking through the “windows” to learn about other people, places, and cultures in the world that are new to them (Bishop, 1990). With Town Is by the Sea, they experienced and grew to respect and understand another place and way of life that was different (i.e., mining, living by the sea) from their own, but also with which there were commonalities they shared (i.e., loving families, fathers going to work, homes).

Students also learned about horizon lines and explored how to use them. I find that students are motivated to write more content when they are inspired by their own artwork. Creating art stimulates their thinking and creativity in ways that beginning with writing a story first doesn’t. While students didn’t write their stories the same day they painted due to time, they remembered the stories behind their paintings. The paintings stayed in their Storying Studio folders until writing time. I like extending projects over several days because students learn that writing is a process and that stories do not happen at one seating or in one day. They do, however, view themselves as authors, artists, and readers and this is the greatest gift I believe I can give them.

References

Bishop, R.S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives: Choosing and using books for the classroom, 6(3), ix-xi.

Martens, P., Martens, R., Doyle, M., Loomis, J., Fuhrman, L., Soper, E., Stout, R., & Furnari, C. (2016). The importance of global literature experiences for young children. In K.G. Short, D. Day, & J. Schroeder (Eds.), Teaching globally: Reading the world through literature (pp. 273-294). Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Fletcher, R., & Portalupi, J. (2001). Writing workshop: The essential guide. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Short, K. (2009). Critically reading the word and the world: Building intercultural understanding through literature. Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature, 47(2), 1-10.

Children’s Literature References

Bang, M. (1999). When Sophie gets angry, really, really angry. New York: Blue Sky Press.

Byrne, R. (2014). This book just ate my dog. New York: Henry Holt.

Freedman, D. (2016). Shy. New York: Viking.

Light, K. (2014). Louise loves art. New York: Balzer + Bray.

Messner, K. (2014). Over and under the snow. Illus. C.S. Neal. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle.

Messner, K. (2017). Up in the garden and down in the dirt. Illus. C.S. Neal. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle.

Queen Rania of Jordan Al Abdullah, & DiPucchio, K. (2010). The sandwich swap. Illus. T. Tusa. White Plains, NY: Disney-Hyperion.

Schwartz, J. (2017). Town is by the sea. Illus. S. Smith. Toronto, ON: Groundwood Books.

Shannon, D. (2000). The rain came down. New York: Blue Sky Press.

Robbie Stout teaches kindergarten at Franklin Elementary School in Reisterstown, Maryland.

WOW Stories, Volume VI, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/wow-stories-volume-vi-issue-1.