“People did great things with their hands”: Telling Stories to Engage with Culture

By Jenna Loomis

Teaching with global literature is important in all classrooms, but especially so in my third-grade classroom. The school where I teach is located in a rural area in the northernmost part of Baltimore County in Maryland. Ninety percent of our school population identifies as white, 4% as Hispanic/Latino, and 6% as all other cultures, including students who identify as two or more races. With little racial diversity throughout our school, it is important to expose students to different cultures and perspectives. This year, in our departmentalized third grade, I taught English Language Arts to a total of 59 students. This included all general education students and three students with Individualized Education Plans (IEP’s).

Every year our school holds an “International Day” when each grade level learns about a country or continent, creates a project based on the learning, engages with guest speakers, and experiences aspects of the cultures about which they are learning. While this day offers students general knowledge, this type of learning often does not promote significant understandings or cultural perspectives. By immersing students in a culture through stories and experiences, they move beyond knowing the surface characteristics of a culture, such as food, festivals, famous people, folklore, and fashion, to understanding the beliefs, values, perspectives, and the diversity that exists within a specific culture (Short, 2007).

So, my challenge was to create a learning experience that fit within the existing structure of International Day but at the same time enhanced my students’ understandings of themselves and people within a culture. Although a single text is not ideal for an intentional teaching and learning experience, I found myself in this situation for a variety of reasons. Nonetheless, I set about creating a valuable learning experience using information provided in the Author’s Note in the book along with video resources I had located online.

Learning Through Ghost Hands

Working with the social studies teacher, we decided to focus on South America because students explored various aspects of culture in different South American countries as part of the social studies curriculum. These curricular cultural topics included government, resources and economics, school life, religion, food and clothing and special customs. The Cave of Hands in the Patagonian region in Argentina offered an intriguing departure from this kind of study. Archaeologists have discovered a cave in which 890 hands have been negative-painted, or stenciled on the walls, along with one foot and a variety of hand-drawn elements such as the sun, indigenous animals, hunting, and a variety of shapes and patterns.

Ghost Hands: A Story Inspired by Patagonia’s Cave of the Hands (2011), written by T.A Barron and illustrated by William Low, tells the story of how one foot may have come to be painted on the wall among the hundreds of hands. The book includes a note to the reader giving information about the cave and reports that the Tehuelche tribe was all but wiped out by settlers who massacred, poisoned, and drove the people off their land so settlers could use it for sheep farming. Rather than focusing on the demise of the tribe or the details of how the foot may have become important enough to paint, I chose to delve deeper into the illustrations and writing to help students explore the values and beliefs of the Tehuelche.

In the story, a boy named Auki, whose name means “little hunter,” sets out to prove that he is worthy of his name. He has been told again that he is not ready to hunt even though he has practiced his skills and patience. He sets out on his own to prove he is “brave enough to face a puma.” When he meets the puma, he falls into a canyon and injures his foot. As he tries to get back to his family before the puma finds him, he finds the entrance to a cave with walls covered with hand prints. At first, Auki thinks the paintings look like ghost hands waving at him. Auki meets Pajar, a strange and unfriendly man who calls himself “the painter of our people.” When Pajar tries to chase Auki away from the cave, the puma appears and threatens them. Auki races toward the puma trying to scare it away and trips on a bowl of paint. While his legs are flailing through the air, Auki’s foot strikes the puma and he saves their lives. Pajar nurses Auki back to health and before painting Auki’s foot, he declares, “I will paint someone very brave, so brave he saved my life.”

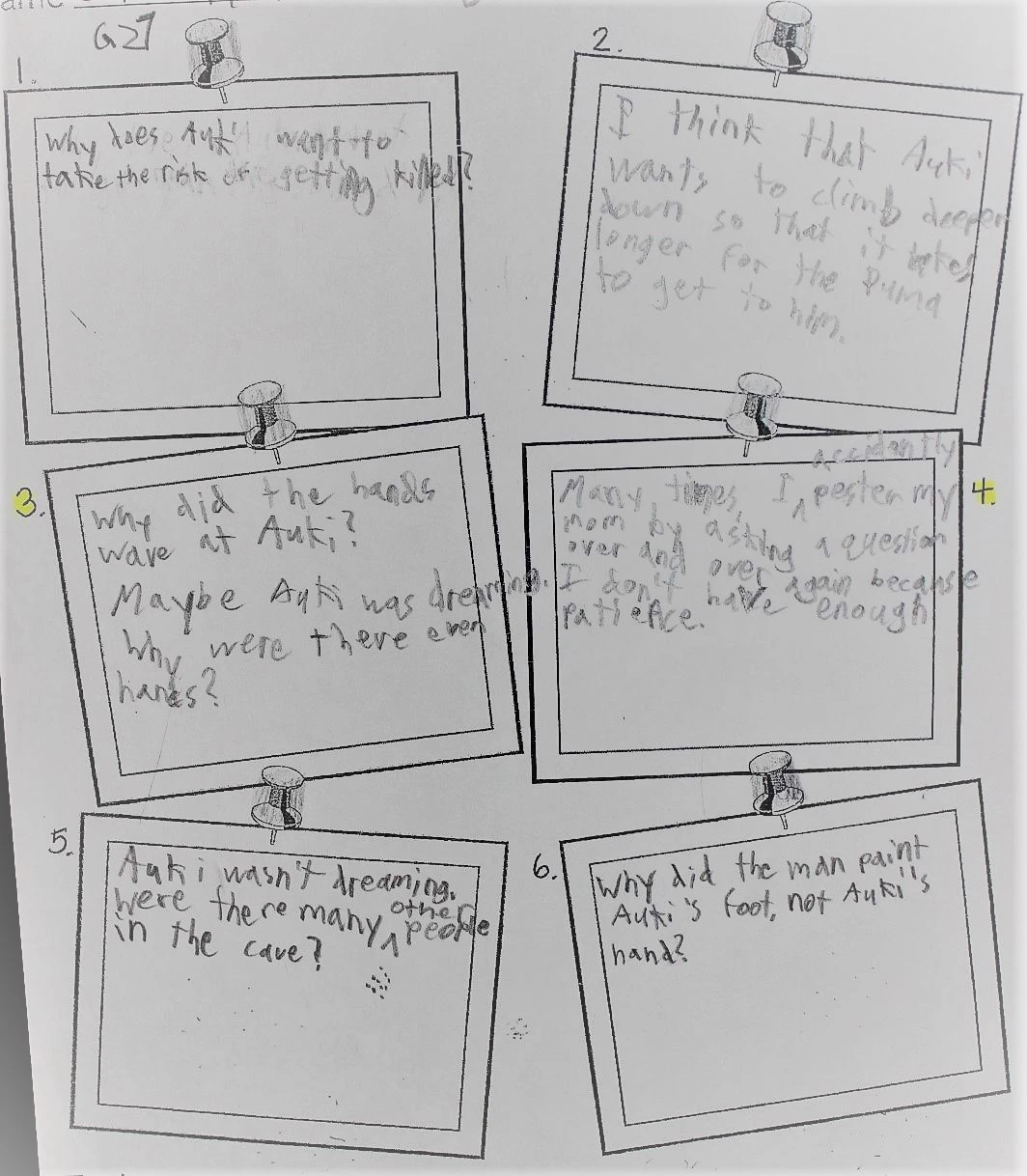

Figure 1: I gave students a note page with six different boxes to record their predictions, questions, and connections as we read.

I gave students a note page with six different boxes to record their predictions, questions, and connections as we read (see Figure 1). I modeled the instructions for students in the first box and we all discussed ideas for the second box before students recorded their ideas. Students recorded their own thinking in the remaining four boxes. Uri’s notes demonstrate his evolving thinking as we read (see Figure 1). On the third note, he wrote “Why did the hands wave at Auki? Maybe Auki was dreaming. Why were there even hands?” His fifth note read, “Auki wasn’t dreaming. Were there many other people in the cave?”

As we continued reading we stopped in strategic places I had marked in the story, such as the end of page that reads, “Ghost hands! My heart galloped like a fleeing herd!” when Auki enters the cave and sees the painted hands. The illustration on this page is a double-page spread with the hands covering two-thirds of the page. The figurative language that reflects Auki’s culture made this a compelling page on which to pause.

Likewise, we stopped after Pajar explains to Auki, “These hands threw spears, carried children, found healing herbs, and pointed to the stars. They protected our people, and also our traditions” (Barron, 2011, np). The accompanying illustration covers both pages, with Auki and Pajar highlighted in the front against slightly blurred images of people behind them holding their hands, haloed in color, high. This page connected the events of the story and begged to be poured over. After some discussion, students jotted on their note page. Megan concluded “I think the hands are the hands of brave hunters.” Another student reflected and wrote, “The hands remind me of war, peace, protection, freedom.” We continued to explore and reflect on the story until its conclusion, pausing on pages that held important story events, language and visual imagery.

Once students understood the basic story elements and plot, they met in literature circles, using ideas from their note pages as conversation starters. As students shared their predictions that were correct, thinking that needed to be changed, and questions and connections, I circulated through the discussion groups and joined the conversations. Students helped each other understand basic aspects of the story as they answered each other’s questions such as:

- “Elders are ghosts?”

- “How can your foot scream?” (When Auki hurt his foot, he said his foot “screamed.”)

- “Why does the old man not want Auki in the cave?”

In their literature circles, they also helped each other understand the Tehuelche’s values and beliefs as they addressed questions such as the following:

- “Why would someone spend so much time painting HANDS? (This was written in capitals to emphasize that it was a strange thing to spend so much time painting.)

- “What does he mean by ‘painter of the people?’

- “Did the boy ever become a hunter?” This question was important because it led to a discussion about the qualities of a hunter--strong, “brave enough to face the puma”, older, and experienced--and why it would be so important for hunters to have these characteristics. We discussed whether Auki’s actions in the story demonstrated those valued characteristics.

- Jason wondered whether Auki would be the painter after Pajar died. This led to a discussion about the qualities considered to be important in the person chosen to be the painter of the people and whether Auki had those qualities. These wonderings also led students back to the end of the story that says, “a boy who became a hunter and a painter.”

- When Pajar explains the hands to Auki, he says, “that secret has been known only by elders. And now…by you.” Jimmy wondered, “Why was the secret only shared with old people and not kids.” This discussion gave us insight into the tribe’s views of older versus younger people.

- Another student shared, “Now I know why it says they tell stories with hands, because there are hands on the wall from the elders.”

Some students made connections:

- Kerry wrote, “This reminds me of when I put my hand on a piece of clay for an ornament so when I was older I would remember how small my hand was,” which led to a discussion in Kerry’s group about why the people might want to remember the hands that were painted on the wall.

- Kaitlyn recorded, “Auki reminds me of me because one time I learned a lesson about patience.” Students connected with being impatient for something that meant a lot to them.

- Uri wrote, “Many times, I accidently pester my mom by asking a question over and over again because I don’t have enough patience.”

After small group conversations, the class gathered and highlighted conclusions that groups drew about the characters, the tribe’s values, and their connections. Ethan decided they painted hands in the cave because “people did great things with their hands.” The hands reflected the values of the people and the important aspects of their lives that they determined were considered “great.” Students’ thinking was further validated when I shared that Tehuelche means “brave people” as this detail was not shared in the book. These small group conversations were amazing!

Sharing Our Understandings

My challenge was to have something to share that conveyed the learning that had taken place. We decided to create brochures about the region and the cave to show parents and students who visited our classroom on International Night.

The brochures highlighted three topics--the geography of the region, the people and the cave. All the information students included in their brochures came from the story, the illustrations, the literature circles, and a short clip from a National Geographic documentary about the region. We used the video to compare how the region was portrayed in the illustrations with actual footage from the area. Students determined that the illustrations were excellent sources of information because they accurately depicted the landscape, animals, and challenges of living in the area. The students’ descriptions of the Tehuelche people on the brochures included:

- The elders were important because they helped out with a lot of things.

- They liked to draw and just tell stories about spirits and other things they do.

- They tell stories with words or hands.

- They tell stories about people who did great things.

- They drew pictures to represent the words.

- The hands represent the history of the people that died for them.

- In these tribes, people tell stories, write stories, and read stories.

- They tell stories of the past and present.

- Why does the tribe tell stories? Telling stories is telling you about the tribe and their history. It tells you about their culture and history.

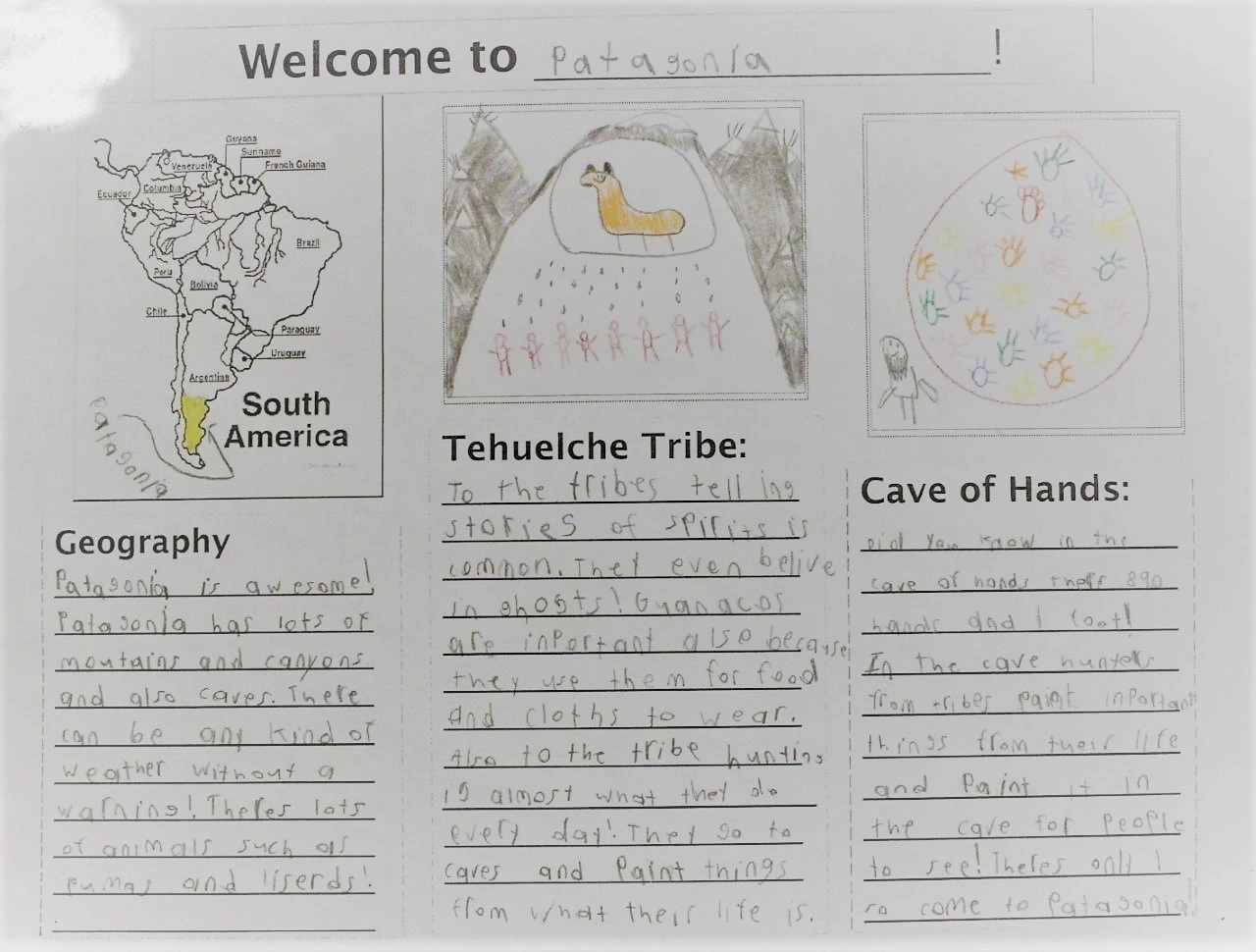

Figure 2: In Annie’s brochure, she discussed the mountains and canyons, the weather, the Cave of Hands, and the Tehuelche, writing, “To the tribes, telling stories of spirits is common…They go to the caves and paint things from what their life is.”

In Annie’s brochure (see Figure 2), she discussed the mountains and canyons, the weather, the Cave of Hands, and the Tehuelche, writing, “To the tribes, telling stories of spirits is common…They go to the caves and paint things from what their life is.”

These brochures demonstrated an understanding about a tribe of people who no longer live in the Patagonian region in South America. In fact, the last of these original Patagonians died in 1960. Rather than reporting only about what they wore, that they hunted guanacos in the canyons, or that a mysterious cave filled with hands can be found in the region, students gained insight and appreciation for a tribe with deep values, respect for the past, and an understanding of the importance of story and remembering in the Tehuelche’s lives.

Figure 3: We created an interactive “Mural of Hands” in the hallway outside our classroom.

We created an interactive “Mural of Hands” in the hallway outside our classroom (see Figure 3). The mural was interactive in the sense that students and visitors added their own hands and wrote about the amazing things they did with their hands. Throughout the night, the mural grew. At a station in our classroom, visitors created their own “negative-painted” handprint with paper and crayons to do rubbings. Ethan’s quote about people doing great things with their hands stood at the top of the mural. Students wrote:

- They help me with sports and writing.

- They help me play piano, building and hugging.

- My hands help to grow more plants and make the environment a better place to live.

- My hands are useful for holding chicks and chickens.

- My hands can cook, take care of a dog, write stories, and play games. I love my hands!

- My hands draw design and create new things.

Later in the week, when we thought about all the great things our hands do listed on our wall, we noticed that our hands tell a story about us, too. Common themes such as playing sports or music, cooking, eating, writing, drawing and all manners of creating, and doing chores showed that many people in our community valued those as important and even “amazing” things they did. We agreed that those activities represent us well, as most students were able to tell stories that were important to them about at least a few activities on that list.

Closing Thoughts

The important things that students identified about their hands tell a story about families whose children attend our school. We were able to connect our experience with the stories the hands in the cave tell about the Tehuelche tribe as we reflected one more time on the words, “My people tell many stories – even one about a boy who became a hunter and a painter. Sometimes they tell those stories with words, sometimes with hands” (Barron, 2011, np). Through their experiences with Ghost Hands students recognized “their places and their particular experiences as part of the universal whole of humanity” (Lehman, Freeman, & Scharer, 2010, p. 19).

References

Barron, T.A. (2011). Ghost hands: A story inspired by Patagonia’s cave of the hands. Illus. W. Low. New York: Philomel Books.

Lehman, B., Freeman, E., & Scharer, P. (2010). Reading globally, k-8: Connecting students to the world through literature. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Short, K. (2007, Spring). Children between worlds: Creating intercultural connections through literature. Arizona Reading Journal, XXXIII(2), 12 – 17.

Jenna Loomis teaches third grade at Seventh District Elementary School in Parkton, Maryland.

WOW Stories, Volume VI, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/wow-stories-volume-vi-issue-1.