Translanguaging in Picturebooks

By Ted Kesler, Meaghan Reilly, and Esther Eng-Tsang

Twenty-four third graders sit in rapt attention as Esther reads aloud the first opening of Love as Strong as Ginger (Look, 1999). Esther speaks the same dialect of Chinese as the grandmother in the story, and after finishing the first opening, she remarks: “You know, this reminds me that I speak Taishanese with my mom, not English. Is that true for any of you? Do any of you speak another language with your parents or grandparents or other family members?” Several students signal “me too” with their hands. They also share the actual names they use to address loved ones, just as Katie does in the story. They then discuss the use of italic and English letters for phonetic spelling of the Chinese words, or pinyin, before Esther turns the page.

We are a teacher educator and two classroom teachers. Meaghan is lead teacher in a self-contained class of 2nd and 3rd grade children with special needs, Esther is a 3rd grade general education teacher, and Ted is an associate professor of elementary and early childhood education at Queens College, the City University of New York (CUNY). We work together in a city public early childhood school, grades pre-K through 3, that serves the local neighborhood. The school serves a predominantly immigrant and economically-disadvantaged population (67% free or reduced-price lunch). Seventy-eight percent of families are Chinese immigrants. Mandarin is the predominant language in the home. Fifty-five percent of students are emergent English learners, and 20% speak two or more languages other than English.

Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy and Translanguaging

We are concerned about addressing issues of social justice and providing culturally sustaining education (Paris & Alim, 2014) to our children. We strive for pedagogy that embraces pluralism, that explores, honors, extends, and, sometimes problematizes students’ heritage and community practices. We aim to make children’s learning more lasting and personally meaningful by connecting content knowledge to their lived experiences and cultural frames of reference. Paris (2012) asserts that, through these practices, academic achievement for children of diverse backgrounds will improve.

With these priorities in mind, we attended a “Social Justice Saturday,” a day of workshops focusing on social justice issues, grades K through 12, sponsored by The Reading and Writing Project of Teachers College. One workshop focused on translanguaging (Garcίa, Ibarra Johnson, & Seltzer, 2017). Translanguaging does not demarcate children’s languages; instead, translanguaging maintains children’s active negotiation of language resources and practices on a continuum in order to express themselves in particular contexts. This concept focuses on processes of interaction, meaning-making, and the agency of speakers. Families and communities are central in Garcίa’s (2009) initial definition, considering how family members have different linguistic abilities, with translanguaging as an inclusive discursive practice that occurs when they all come together. The presenters posed the challenge: how can we encourage translanguaging opportunities in our everyday classroom work?

Exploring Translanguaging in Picturebooks

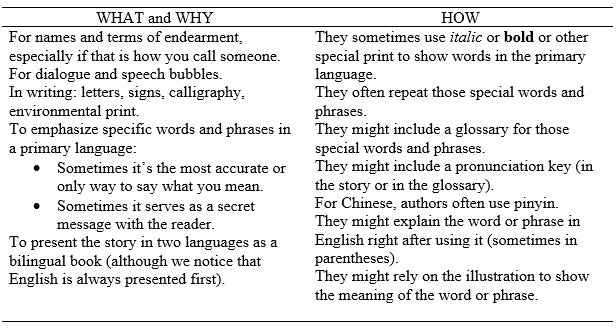

Meanwhile, back at our school, we were actively ordering recent picturebooks that provide windows and mirrors and sliding doors (Sims Bishop, 1990) for children. With our new challenge of translanguaging, we began noticing authors’ and illustrators’ use of translanguaging in picturebooks. We noticed authors’ use of italics or bold print to highlight special words and phrases in the featured language. We saw how authors provide context clues, such as using a key phrase repeatedly, or repeating the meaning of these special words and phrases in English, or showing the meaning through actions in the illustrations. Some books provide a glossary of terms. We noticed ways that illustrators show sociocultural meanings of these words and phrases. For example, in Fiesta Babies (Tafolla, 2010), the meaning of coronas, salsa, mariachi, cha-cha-cha, fiestas, siestas, besos, and abrazos is apparent first through the illustrations before getting to the glossary on the back page.

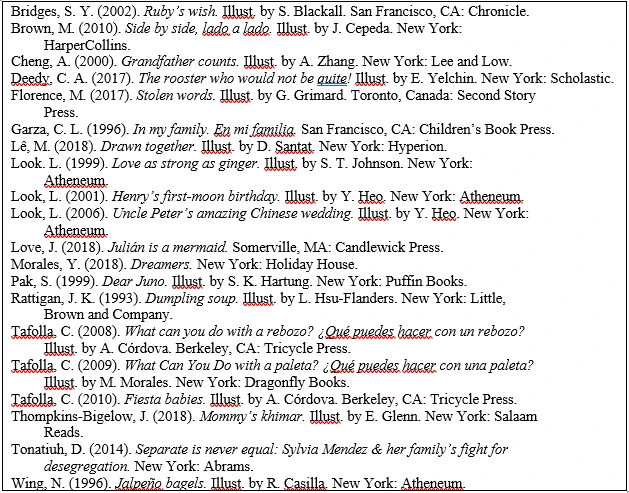

Figure 1. Picturebooks We Used with Examples of Translanguaging

Figure 1 shows the picturebooks we explored with students, conducting interactive read-alouds for most of these books. We explained translanguaging as the author’s and illustrator’s fluid use of more than one language to present particular cultures to readers. We discussed how and why authors make these decisions.

During one reading workshop session, students met in small groups with small stacks of these books. We gave them sticky notes to mark places where they found examples of translanguaging, with the guiding question: how and why do authors and illustrators use translanguaging in their books? At the end of reading workshop time, we reconvened to share our discoveries. Table 1 shows the discoveries students made.

Authors'/Illustrators' Use of Translanguaging in Picturebooks

In another reading workshop session, students returned to these books to find out how authors and illustrators show the meaning of words and phrases in the primary language. We highlighted authors’ use of a glossary, the use of a pronunciation key, and discussed pinyin. We shared examples of showing meaning of primary language words and phrases in the illustrations, such as for Fiesta Babies (Tafolla, 2010). Students picked up on authors’ use of repetition of important words and phrases. For example, in Dumpling Soup (Rattigan, 1993), mandoo (dumplings in Korean) is used throughout the book. Even though we had emphasized context clues for new vocabulary all year, students now seemed to grasp the use of context clues to explain primary language.

Applying Translanguaging to Our Writing

We wanted children to transfer what they were learning to their own writing, leading to discussions like the one we presented in our opening vignette. We were in the midst of a memoir study, in which we emphasized writing authentic, meaningful moments in our lives. It seemed hypocritical to expect students to write their memoirs using English only, when their authentic moments included speaking to their grandmothers in Mandarin or calling their dads Papί or using their cultural terms for food such as roti. We discussed how they use translanguaging in their own lives outside school and discovered that translanguaging was a common practice for emergent English learning students. “You know, like all these authors and illustrators, you could use translanguaging in your memoirs if it will help you tell your story truthfully, more like the way it really happened.” Their faces seemed to open up like a thank you.

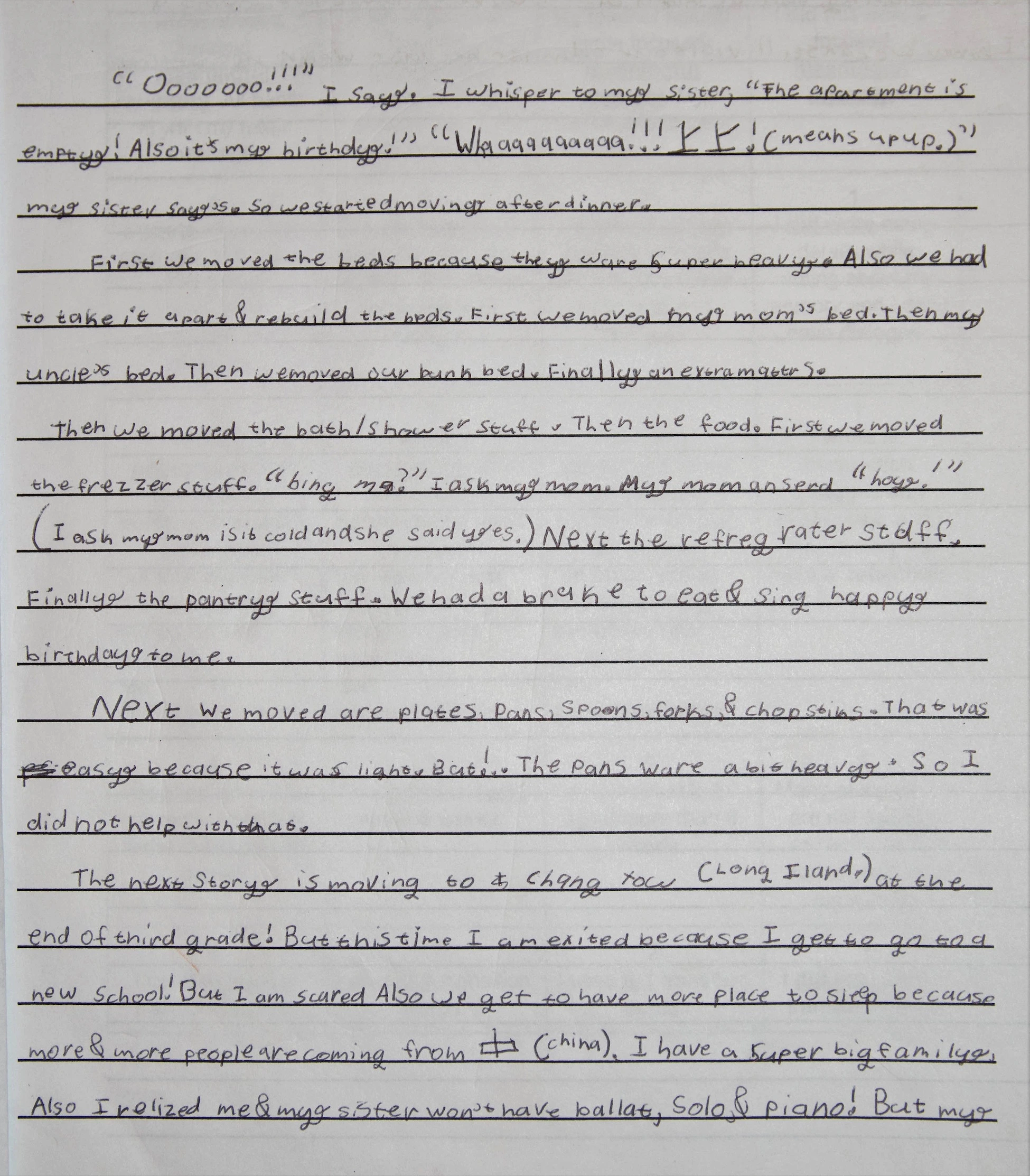

Figure 2. An example of translanguaging in Esther’s memoir draft.

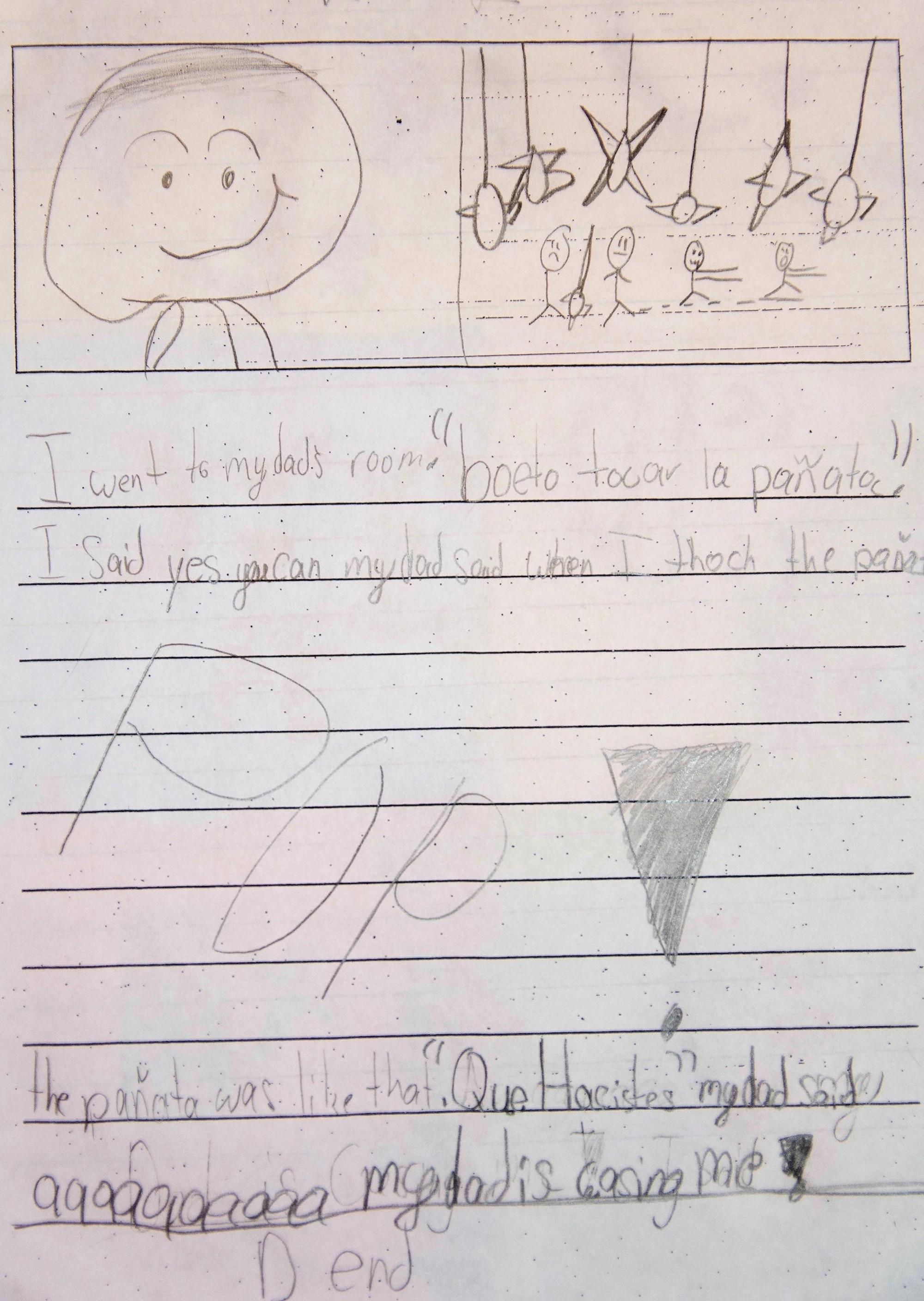

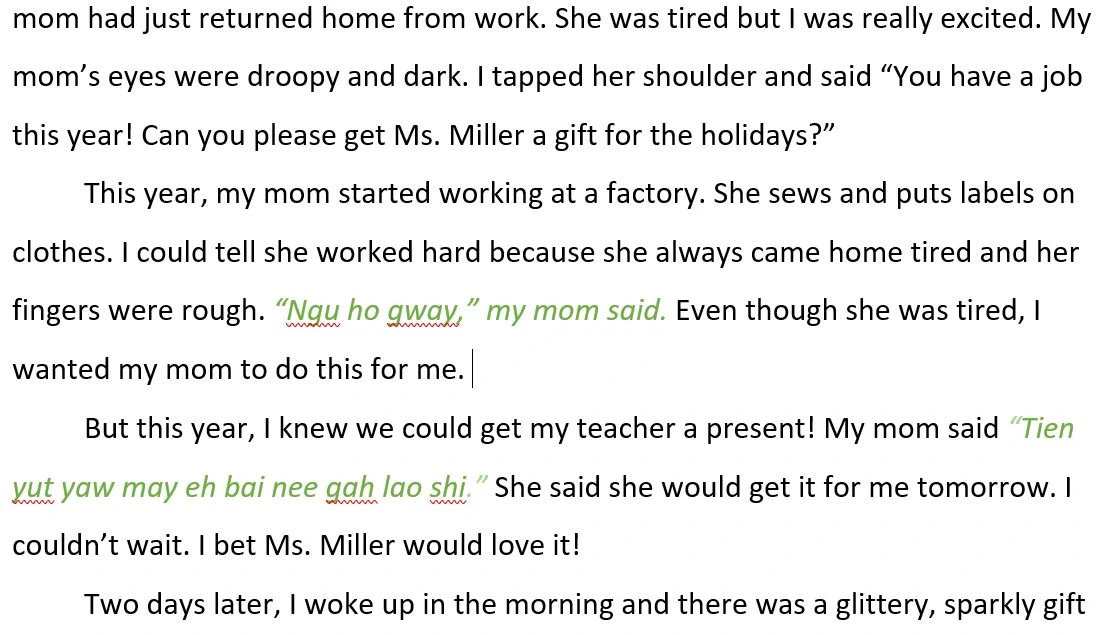

Esther demonstrated with her own memoir, replacing her English writing with pinyin, “trying my best” to represent the Taishanese sounds with English letters (see Figure 2), and then embedding context clues in English. We then challenged students, asking “how might you use what we learned about translanguaging in your own memoirs?” Jeremy, one of Meaghan's students, wrote about when he accidentally popped the piñata his dad was making for his birthday. Figure 3 shows page 2 of his story.

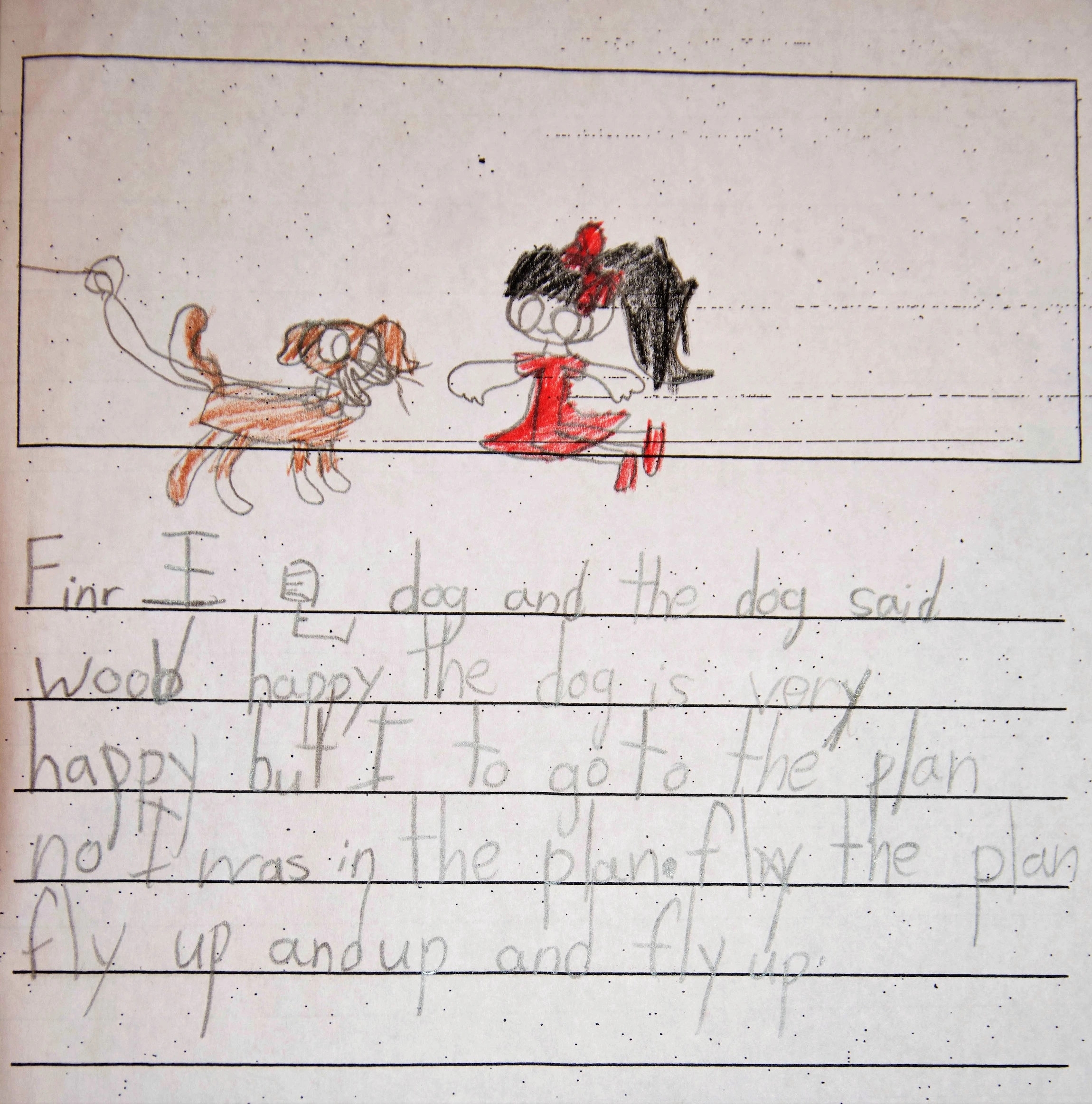

The picture shows his smiling face and children playing at the party with piñatas hanging. He uses Spanish dialogue in interactions with his dad: “Puedo tocar la piñata?” he asked his dad. And after he popped the piñata, his dad exclaimed, “Qué hiciste?” Grace used Chinese characters for some words in her memoir about her visit to relatives in China. In Figure 4, Grace says goodbye to the dog before leaving on the plane. She wrote the dog’s name using Chinese characters. Another student, Moosa, used the words Mameya for Mother and Baba for Father in his memoir. His mother is from Afghanistan, and these are the names of endearment he calls them.

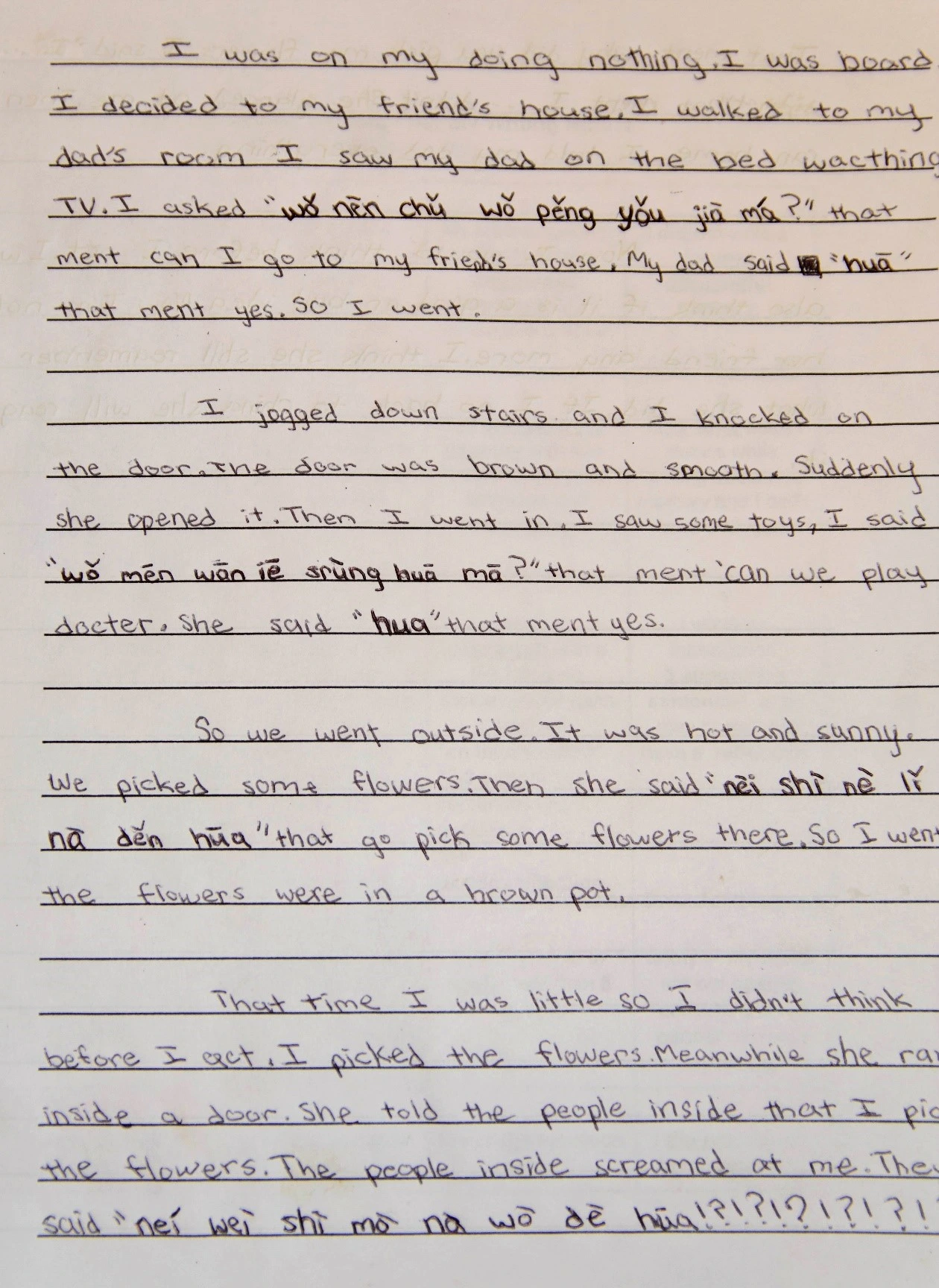

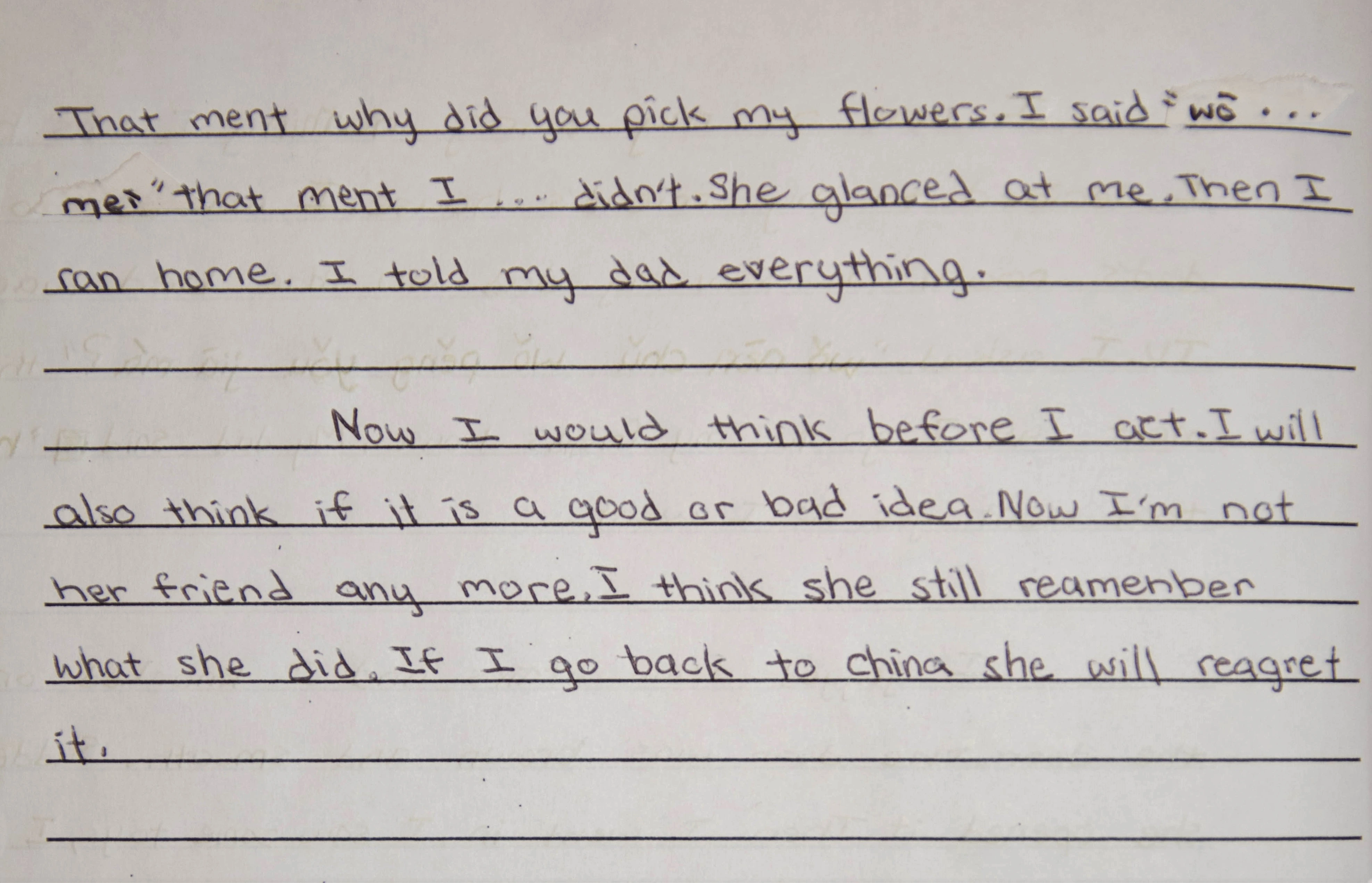

In Esther’s class, several students used pinyin to represent dialogue in Chinese. Figures 5a and 5b are Yitong’s memoir about when she was tricked by another girl to pick flowers from a flower pot in China, and then got in trouble. Like some other children, she bolded the pinyin writing. Wendy wrote the title to her memoir in both English and Chinese: “Learning Why Moving Can Be Fun!” (Figure 6). Then, in her story, she used both Chinese characters and pinyin (Figure 7). For example, she wrote Up, Up! and China using Chinese characters, but used pinyin for dialogue between her and her mother and for Long Island (which she wrote as Chang Xow). Across all examples, the children gave strong context clues for their use of primary languages from their household, usually by immediately translating into English. As a result, they also applied sophisticated punctuation, such as off-setting the translation using commas or parentheses.

Opening Our Classrooms to Translanguaging

We have been encouraged by these first steps into opening our classrooms to translanguaging. We are learning to sustain “linguistic, literate, and cultural pluralism as part of the democratic project of schooling” (Paris, 2012, p. 95). We believe supporting students’ linguistic and cultural flexibility will prepare them for success in the world (Garcia, 2009). We are considering encouraging children to show cultural artifacts in illustrations, as a common strategy used by illustrators. We want to encourage children’s use of translanguaging in nonfiction reading and writing. For example, where does translanguaging occur in the nonfiction books we read? How might we apply translanguaging when we write informational books? We also are challenged by the idea of exploring and then composing our own bilingual books, as some of the authors we studied do (for example, Brown, Garza, and Tafolla). We continue to explore ways to practice culturally responsive teaching and bring translanguaging into our content area work in math, science, social studies, music and art.

True to “Social Justice Saturday” and our intentions for culturally sustaining teaching (Paris, 2012), this first opportunity to express meaning across languages in writing has given children confidence. They approach writing tasks with more flexibility, knowing that they can use a broader language repertoire that is much more congruent with their lives outside school. They are more careful readers, who now call our attention to instances of translanguaging in books they read, but also other instances of author’s and illustrator’s craft, such as deliberate use of fonts or layout or cultural symbols in the illustrations, or use of metaphors and cultural references in writing. They are more joyful learners because of the bridges we are creating between home and school.

References

Garcίa, O. (2009). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Garcίa, O., Ibarra Johnson, S., & Seltzer, K. (2017). The translanguaging classroom: Leveraging student bilingualism for learning. Philadelphia, PA: Caslon.

Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educational Researcher, 41(3), 93-97.

Paris, D., & Alim, H. S. (2014). What are we seeking to sustain through culturally sustaining pedagogy? A loving critique. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 85-100.

Sims Bishop, R. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives, 1(3), ix–xi.

Esther Eng-Tsang teaches third grade at the Active Learning Elementary School (PS 244Q) in Flushing, New York.

Ted Kesler is an Associate Professor in elementary and early childhood education at Queens College, the City University of New York (CUNY).

Meaghan Reilly is a second and third grade classroom teacher of children with special needs at The Active Learning Elementary School (PS 244Q) in Flushing, New York.

WOW Stories, Volume VI, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/wow-stories-volume-vi-issue-2.