Interrogating Anti-Asian Racism: Children’s Literature as a Nexus for Racial Literacy

Wenyu Guo

This article draws on my reflections from a year-long study in a community-based book club in a southeastern U.S. Chinese Heritage Language (CHL) school during which I read and discussed Asian American picturebooks with local Chinese immigrant children for nearly four years. These experiences demonstrate that children’s literature depicting authentic racialized history fosters students’ understanding of race, provides suggestions for using children’s literature with supplemental material to teach racialized history, and facilitates race talk. This article also includes a select list of picturebooks along with relevant resources.

Children’s Literature with Supplementary Material as Tools to Foster Race Talk

Studies have shown that children are already talking about race and questioning racial inequities in school (Falkner, 2019). However, the school curriculum frequently falls short in providing an authentic accounting of racial conditions, thus neglecting to empower communities and offer strategies for dismantling racism with the so-called “white social studies” (Chandler & Branscombe, 2015, p. 63). Given the minimal support from the school and the pervasive deficit-oriented narrative surrounding Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) and immigrants, there is a large potential for children, especially ones who come from minoritized groups to recycle and internalize these racialized messages (Boutte & Muller, 2018). Hass (2017) found that students provided reasons for unjust gender-related experiences and developed hypotheses around race and gender inequalities. Similarly, An (2020) observed that her elementary-aged daughter perpetuated stereotypes while reading, such as associating “whiteness with Americanness” and viewing “racism as a thing of the past” (p. 179).

Furthermore, during nearly four years of book club meetings, I observed that students from Chinese immigrant families often generated hypotheses to rationalize and validate racial inequities. These hypotheses included framing racism as a mental health issue and regarding racism from a Black/white binary, viewing racism as an outdated concern, justifying racism toward immigrants due to English language proficiency, and employing colorblindness to sidestep discussions about skin color and race (Guo, 2023).

One of the functions of children’s literature is “to explain and interpret national histories – histories that involve invasion, conquest, violence, and assimilation” (Bradford, 2007, p. 97). Typically, reading and discussing historical fiction is a common curricular tool used to initiate talk about race and address racism in the early childhood and elementary classroom (Boutte & Muller, 2018; Boutte et al., 2011; Brooks et al., 2018). Many studies have demonstrated that reading racialized narratives about students’ historical counterparts supports minoritized students in reflecting on their racial experiences and taking a sociocultural stance (Bishop, 2007; Brooks, 2006; Brooks & Browne; 2012). Concerning the absence of Asian American experiences and narratives in K-12 schools (An, 2016, 2022), children’s literature is a major teaching venue to examine diverse beliefs, values, and histories of Asian Americans in the United States. Prior research demonstrates that children’s literature featuring cultural attributes and authentic experiences of Asian Americans fosters children’s understanding of their real-life issues and facilitates children’s critical awareness of social inequity and injustice (Chen, 2019; Son, 2021).

However, historical picturebooks alone without supplementary materials on historical background are not sufficient to support students in developing their critical awareness around race and racism (Daly, 2022; Price-Dennis et al., 2016; Rodriguez & Kim, 2018). From extensive experiences reading these books with students, I was astonished by the diverse interpretations of students. For example, when we read Coolies (Yin, 2003), students’ understanding of racism partially disrupted dominant racialized narratives, while other stereotypes were solidified and reproduced. Students enacted and solidified master narratives, including English proficiency as the reason for racial segregation, and failed to see the underlying racism behind the stories (Guo, 2024). Although we read and discussed the characters and plots together, these stories inadequately depict the pertinent historical context and lack explicit engagement with the concepts of racism and systemic power dynamics. As a result, they offer an ambiguous representation of the social landscape, casting Asian Americans as passive victims subjected to discrimination without explicitly acknowledging external factors contributing to their experiences.

Thus, solely reading and discussing historical picturebooks is not sufficient for students to understand racism as a social construct. Students required multiple resources and a gradual process to untangle their interpretations, simultaneously confronting their assumptions shaped by the daily racial and social realities they encounter. Crucially, this process needed to be consistent and repeated over time with a variety of texts (e.g., children’s literature, authentic historical texts, images, documentary films, etc.). Thus, it is crucial for educators and parents to offer additional materials to help children comprehend the historical context intertwined with complex socioeconomic factors and international diplomacy. This support is essential to empower children to confront anti-Asian discourse on a broader scale, moving beyond the individual level and fostering an understanding of institutional racism.

Suggestions for Educators and Parents

Two key suggestions to K-12 educators and parents are offered based on my extensive literacy engagement with Asian American students, including exploring Asian American histories and addressing anti-Asian racism through the use of children’s literature and supplementary materials. Firstly, educators should purposefully diversify their classroom libraries with Asian American children’s literature that not only represents diverse narratives but also consciously avoids perpetuating stereotypes, considering the limited attention given to Asian American communities and narratives in addressing anti-Asian racism within school curricula (An, 2022). Secondly, in addition to selected children’s literature, educators should integrate supplementary material including extended readings, images, and videos to enhance students’ understanding of the history and realities of Asian Americans.

Choosing Children’s Literature to Disrupt Anti-Asian Racism

Given the historical presence of slurs, stereotypes, and assumptions in children’s literature (Au, Brown, & Calderon, 2016; Mo & Shen, 2003), the selection of culturally authentic Asian American literature becomes crucial. Aoki (1981) stressed that such literature should authentically reflect the day-to-day realities of Asian American lives and transcend stereotypes, particularly those portraying Asian Americans as the model minority. While the past two decades have seen a substantial increase in Asian American literature, many texts continue to reinforce stereotypes, such as the overachieving model minority and Asian Americans as exotic foreigners, failing to capture the rich diversity within Asian America. For example, in Lissy’s Friends (Lin, 2007), about a Chinese American girl’s schooling experience is isolated, Lissy is depicted as the “other” through dressing and speaking distinctly different from classmates who are white and students of color in the narrative, making it challenging for students to connect with her.

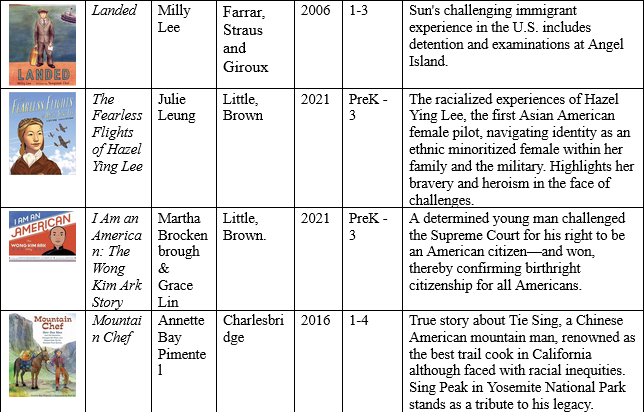

Drawing on a cultural insider perspective (Bishop, 2003) and teaching experiences, I present the following criteria for selecting Asian American texts which foster talk about race and disrupt anti-Asian racism in classroom and families. Some of the suggested Asian American children’s literature is provided in Table 1.

- Choose stories depicting the racialized experiences of Asian Americans. Some examples of Asian American racialization are building the Transcontinental Railroad, the Chinese Exclusion Act, the imprisonment of Japanese Americans, the creation of harsh immigration policies, the history of detention at Angel Island, and the Model Minority Myth.

- Avoid stories solely depicting Asian Americans as victims.

- Choose stories that highlight Asian American contributions and heroism.

- Choose stories that highlight Asian American activism within the Civil Rights Movement.

Table 1. Suggested Children’s Literature on Chinese American Experiences

Incorporating Supplementary Material to Facilitate Race Talk

Contrary to the common practice of using a single text to initiate critical conversations, Daly (2022) and Price-Dennis et al. (2016) found that incorporating supplementary texts along with children’s books proved beneficial in scaffolding students in discussing racism as both historically and contemporarily relevant. They documented increased participation in critical discussions of race and racism. This rise in engagement was attributed to the innovative curriculum, providing students with diverse entry points for discussing the topic.

Guo (2023) developed an innovative Asian American curriculum centered on dismantling anti-Asian racism and exploring Asian American activism. This curriculum integrates children’s literature with supplementary materials to enhance the learning experience, cultivating active engagement among Chinese American students and fostering students’ learning about racism in a critical way. For example, while reading Paper Son (James, 2013), teachers can add extended reading, such as “Bound for Gold Mountain,” a chapter from Angel Island: Gateway to Gold Mountain written by Russell Freedman (2013), and documentary films, such as The Dark History of the Chinese Exclusion Act by Robert Chang, and Breaking Ground, one of the episodes of Asian Americans which is a five-hour film series that centers on Asian American history. These supplementary materials scaffold students’ learning about the racialization of Chinese Americans under Chinese Exclusion Act with sufficient historical background.

The incorporation of multimodal texts that offer historical context allows students to access relevant information while constructing their understanding of contemporary issues. As revealed in my findings, most participants generated master narratives about racial injustices based on their own limited experiences with racial stereotypes and mistreatment of racial minorities. Due to the limitations of their personal experiences, the interpretations they formed often downplayed anti-Asian racism and created explanations and presumptions for a whitewashed perspective. Therefore, it is essential for researchers and teachers to carefully choose extended texts that offer historical context, enabling them to comprehend current events as products of the persistent beliefs and practices that have been carried forward from the past.

Thus, I suggest educators incorporate supplementary materials and include extended readings on historical context and social events, authentic photographs, documentary films, educational videos, as well as contemporary cartoons or artwork in their curriculum. All these materials should authentically depict the racial experiences of Asian Americans in the United States with both historical and contemporary relevance.

More Resources

This section contains recommendations for primary sources pertaining to Asian American history as well as websites with lists of Chinese American picturebooks. These sources are selected for their capacity to accentuate the heroism and activism of Asian Americans while acknowledging the ways Asian Americans have been racialized. For example, the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center website has lessons linked to objects and artifacts in Smithsonian collections as well as links to videos and books about Filipina female resistance fighters during World War II. Similarly, the resources for finding Chinese American picturebooks include book lists selected by using critical scholarship. For example, the Guide for Selecting Anti-Bias Children’s Books (Derman-Sparks, 2016) urges readers to select books that avoid stereotypes and tokenism, and to choose books that will help children feel represented and seen.

Primary Sources About Asian American Histories

- Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center

- Primary Source Set about Japanese American incarceration at the Library of Congress

- History of Angel Island Immigration Station

- Asian American history by PBS

- South Asian American Digital Archive

Asian American Picturebooks

- Asian/Pacific American Librarians Association

- We Need Diverse Books

- Guide for Selecting Anti-Bias Children’s Books

- Chinese American Family: A parent’s guide to Chinese American children’s books

- American Writers Museum: 14 Picture books featuring Asian families by 14 Asian American authors

- Represent Asian Project: 12 Children’s books by Asian authors

These resources are intended to aid in selecting both fiction and nonfiction texts to share with children, thereby fostering their development of antiracist perspectives. Children’s literature serves as a valuable starting point for discussions surrounding heritage, race, and ethnicity, laying the foundation for the development of racial literacy.

Conclusion

This article explores the reactions of Chinese American children to picturebooks portraying the Asian American racialized experience in the United States. It delves into how merely reading and responding to these texts does not suffice in cultivating antiracist attitudes and racial literacy. To effectively foster antiracist teaching and learning, students require exposure to diverse perspectives and insights from various sources, including fiction, trade books, and primary materials.

With these insights and the recommended resources, I advocate for educators to carefully choose authentic children’s literature that accurately depicts the realities of Asian Americans, both of historical and contemporary relevance, and to integrate diverse resources in their classrooms. In this way, educators can effectively foster meaningful discussions about race and the experiences of Asian Americans, both past and present, with their students. It’s important to recognize that combating racism is an ongoing process, not a one-time effort. Consistent reading and reflection are essential components in this journey.

References

Guo, W. & Sun, Y. (2024). “U.S. and China can be friends for once”: Chinese immigrant children engage in transnational literature in a community-based book club. The International Handbook of Literacies in Families and Communities. (Eds, Edwards, P., Compton-Lilly, C. & Li, G.). Edward Elgar Publishing.

An, S. (2020). Learning racial literacy while navigating white social studies, The Social Studies, 111:4, 174-181.

An, S. (2022). Re/presentation of Asian Americans in 50 states’ K–12 U.S. History standards, The Social Studies, 113:4, 171-184.

Aoki, E. M. (1981). “Are You Chinese? Are You Japanese? Or Are You Just a Mixed-up Kid?” Using Asian American children’s literature. The Reading Teacher, 34(4), 382-385.

Au, W., Brown, A. L., & Calderón, D. (2016). Reclaiming the multicultural roots of US curriculum: Communities of color and official knowledge in education. Teachers College.

Bishop, R. S. (2003). Reframing the debate about cultural authenticity. In D. L. Fox & K. G. Short (Eds.), Stories matter: The complexity of cultural authenticity in childrens literature (pp. 25–40). National Council of Teachers of English.

Bishop, R. S. (2007). Free within ourselves: The development of African American children’s literature. Greenwood.

Boutte, G. S., López-Robertson, J., & Powers-Costello, E. (2011). Moving beyond colorblindness in early childhood classrooms. Early Childhood Education Journal, 39, 335-342.

Boutte, G., & Muller, M. (2018). Engaging children in conversations about oppression using children’s literature. Talking Points, 30(1), 2-9.

Bradford, C. (2007). Unsettling narratives: Postcolonial readings of children’s literature. Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Brooks, W. (2006). Reading representations of themselves: Urban youth use culture and African American textual features to develop literary understandings. Reading Research Quarterly, 41(3), 372–392.

Brooks, W., & Browne, S. (2012). Towards a culturally situated reader response theory. Children’s Literature in Education, 43, 74-85.

Brooks, W. M., Browne, S., & Meirson, T. (2018). Reading, sharing, and experiencing literary/lived narratives about contemporary racism. Urban Education. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085918789733

Chandler, P. T., & Branscombe, A. (2015). White social studies: Protecting the white racial code. In P.T. Chandler (Ed.), Doing race in social studies: Critical perspectives (pp. 61-88). Information Age Publishing.

Chang, R. S. (2017). Whitewashing precedent: From the Chinese exclusion case to Korematsu to the Muslim travel ban cases. Case W. Res. L. Rev., 68, 1183.

Chen, Y. W. (2019). Chinese transnational adolescents’ responses to multicultural children’s literature in culture circles. [Doctoral Dissertation, Boise State University]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Daly, A. (2022). Race talk moves for racial literacy in the elementary classroom. Journal of Literacy Research, 54(4), 480–508.

Derman-Sparks, L. (2016). Guide for selecting anti-bias children’s books. Teaching for Change Books.

Falkner, A. (2019). “They need to say sorry:”Anti-racism in first graders’ racial learning. Journal of Curriculum, Teaching, Learning and Leadership in Education, 4(2), 37.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum.

Guo, W. (2023). Exploring literary responses to culturally relevant texts through an AsianCrit lens: A collective case study of Chinese American students in a community-based book club (Order No. 30528548) [Doctoral dissertation, University of South Carolina]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Hass, C. L. (2017). Learning to question the world: Navigating critical discourse around gender and racial inequities and injustices in a second and third grade classroom (Doctoral dissertation, University of South Carolina).

Lewison, M., Flint, A. S., & Van Sluys, K. (2002). Taking on critical literacy: The journey of newcomers and novices. Language arts, 79(5), 382-392.

Luke, A., & Freebody, P. (1999). A map of possible practices: Further notes on the four resources model. Practically primary, 4(2), 5-8.

McLaughlin, M., & DeVoogd, G. (2004). Critical literacy as comprehension: Expanding reader response. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 48(1), 52-62.

McLaughlin, M., & DeVoogd, G. (2020). Critical expressionism: Expanding reader response in critical literacy. The Reading Teacher, 73(5), 587-595.

Mo, W., & Shen, W. (2003). Accuracy is not enough: The role of cultural values in the authenticity of picture books. Stories matter: The complexity of cultural authenticity in children’s literature (pp. 198-213). National Council of Teachers of English.

Price-Dennis, D., Holmes, K., & Smith, E. E. (2016). “I thought we were over this problem”: Explorations of race in/through literature inquiry. Equity & Excellence in Education, 49(3), 314–335.

Rodriguez, N, N. & Kim, E. (2018). In search of mirrors: An Asian critical race theory content analysis of Asian American picturebooks from 2007 to 2017. Journal of Children’s Literature, 44(2), 17-30.

Shor, I. (1999). What is critical literacy? Journal for Pedagogy, Pluralism, & Practice, 4(1), 1–21.

Son, Y. (2021). A trilingual Asian-American child’s encounters with conflicting selves in the figured worlds of a multicultural book club. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 0(0), 1–15.

Vasquez, V. (2010). Critical literacy isn’t just for books anymore. The Reading Teacher, 63(7), 614-616.

Children’s Literature Cited

Brockenbrough, M. & Lin, G. (2021). I am an American: The Wong Kim Ark story. (J. Kuo, Illus.). Little, Brown.

Freedman, R. (2016). Angel Island: Gateway to Gold Mountain. Clarion.

James, H. F. (2013). Paper Son: Lee’s journey to America. (W. Ong, Illus.). Sleeping Bear Press.

Lee, M. (2006). Landed. (Y. Choi, Illus.). Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Katrina, C. (2004). Kai’s journey to Gold Mountain: An Angel Island Story. (G. Utomo, Illus.). Angel Island Association.

Leung, J. (2021). The fearless flights of Hazel Ying Lee. Little, Brown.

Lin, G. (2007). Lissy’s friends. Viking.

Pimentel, A. (2016). Mountain Chef. (R. Lo, Illus.). Charlesbridge.

Yin (2003). Coolies. (C. Soentpiet, Illus.). Penguin.

Yin (2006). Brothers. (C. Soentpiet, Illus.). Penguin.

Wenyu Guo is an Assistant Professor of Literacy Studies in the College of Education at the University of South Florida, Tampa. Her research takes a critical perspective to examine how agency, identity, and power among Asian transnational families and adolescents are constructed as they engage in literacy practices to make sense of their lives.

Authors retain copyright over the vignettes published in this journal and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under the following Creative Commons License:

WOW Stories, Volume XI, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on work by Wenyu Guo at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/xi-1/3.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551